7 Cranial Nerve VII

Facial

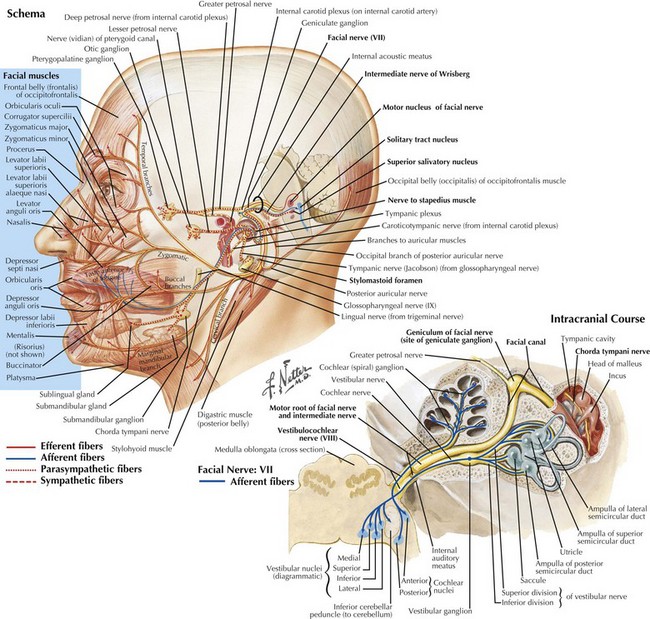

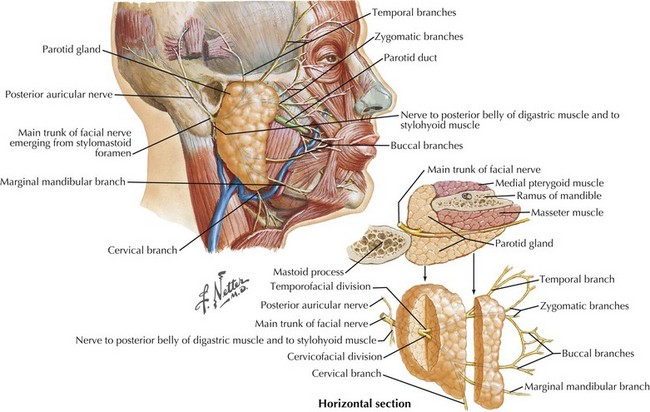

Facial nerve (CN-VII) lesions are the most common cranial mononeuropathy. This is one of the most complex cranial nerves having multiple functions (Fig. 7-1). It has a long and somewhat circuitous course with four primary components. (1) Motor fibers, which constitute the major division and serve the primary function of CN-VII: innervating the muscles of facial expression (unilateral, complete facial weakness is the hallmark of almost all facial neuropathies); (2) autonomic fibers, which are responsible for lacrimal, salivary, and mucous secretions; (3) special sensory fibers, which provide taste from the anterior two thirds of the tongue; and (4) general sensory fibers, which innervate the external auditory canal and a small area behind the ear.

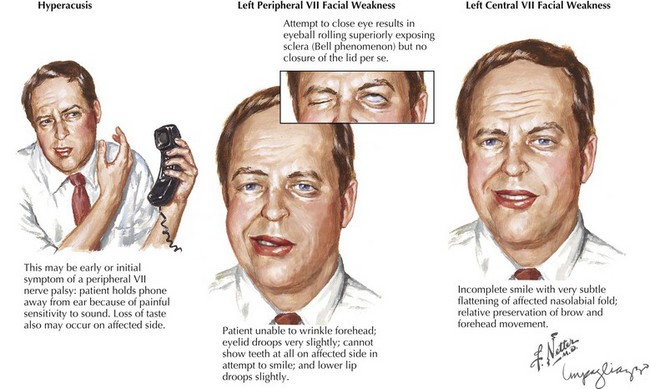

When a patient presents with facial weakness, differentiation should be made between peripheral facial nerve lesions and CNS processes. With the latter, when the patient is relaxed, subtle suggestions of a facial nerve lesion may be appreciated by nasolabial fold flattening on the affected side. Brain lesions such as cerebral infarction, tumor, inflammation, or demyelination are often associated with other findings that can help with localization. For example, a small lesion near the Broca area may result in motor aphasia and facial weakness. Larger lesions affecting a significant portion of a hemisphere, as with large hemispheric strokes, cause a constellation of symptoms, including face, arm, and leg weakness and sensory loss; gaze deviation; and neglect or aphasia. Posterior limb lesions of the internal capsule result in face, arm, and leg weakness without sensory, visual, or cognitive changes. While peripheral facial weakness involves the upper and lower part of the face to the same degree, upper motor neuron lesions typically present with a gradient of weakness (Fig. 7-2), with relative preservation of movement in the brow and forehead (orbicularis oculi and frontalis muscles). This is due to presumed dual hemispheric innervation of the forehead muscles. In addition, corticobulbar tract involvement, as in various suprabulbar palsies, leads to absence of voluntary facial movement but retained reflexive movements such as in response to emotional stimuli.

Anatomy

Intrapontine Portion

CN-VII consists of two primary roots (Fig. 7-1). The larger division carries somatic motor fibers and has its origin within the facial nucleus in the caudal pons, where it lies adjacent to the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve (CN-V). It then passes dorsally and rostrally to curve around the abducens nerve (CN-VI) nucleus (internal genu) and exits the brainstem at the bulbopontine angle between CN-VI and CN-VIII. Its smaller component, the nervus intermedius (intermediate nerve of Wrisberg), contains a combination of autonomic, special sensory (taste), and general sensory fibers. Its preganglionic parasympathetic fibers arise from the superior salivatory nucleus, relay through the pterygopalatine and submandibular ganglions, and eventually provide efferent function for lacrimation and salivation. The remaining intermediate nerve fibers carry taste and general somatic sensation and have their primary cell bodies in the geniculate ganglion and ultimately terminate within the nucleus solitarius and the spinal tract of CN-V, respectively.

Peripheral CN-VII

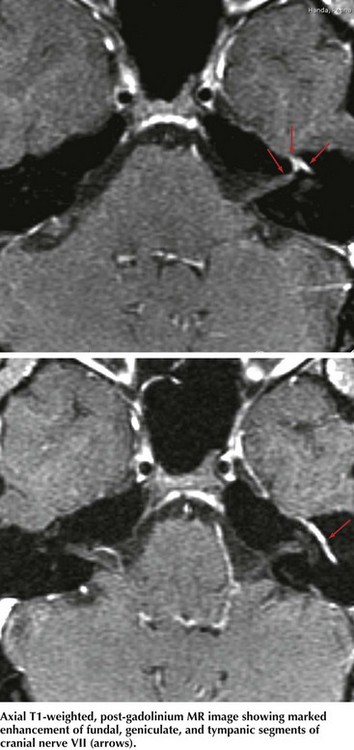

Both roots of CN-VII leave the brainstem to enter the temporal bone via the internal auditory meatus, where they accompany the auditory nerve (CN-VIII) passing through the internal auditory canal (Fig. 7-1, bottom). CN-VII continues to the periphery through the facial canal; this segment has five parts, based on their relation to surrounding anatomic structures. (1) The labyrinthine segment passes above the labyrinth and leads anterolaterally to the geniculate ganglions that contain the cell bodies of CN-VII afferents. (2) At this site, the canal abruptly turns posteriorly and forms the external genu of CN-VII. (3) The greater petrosal nerve originates here; it carries preganglionic parasympathetic fibers to the pterygopalatine ganglion, where they synapse and subsequently direct postganglionic fibers to the lacrimal gland. (4) The tympanic segment of CN-VII travels posteriorly and laterally along the medial wall of the middle ear. At the posterior wall of the middle ear, the facial canal changes its course and travels inferiorly toward its exit at the stylomastoid foramen. (5) The vertical portion is named the mastoid segment and has two important branches: proximally, the stapedius nerve arises to innervate the stapedius muscle; more distally, the chorda tympani branches and exits the facial canal and, after traversing the middle ear, joins the lingual nerve belonging to the third division of CN-V. The chorda tympani contains preganglionic parasympathetic fibers that synapse within the submandibular ganglion to innervate the submandibular and sublingual glands. The chorda tympani also carries taste fibers. Their cell bodies originate within the geniculate ganglion, mediating taste sensation from the anterior two thirds of the tongue.

Soon after leaving the skull at the stylomastoid foramen, the distal CN-VII gives rise to several small motor branches innervating the posterior auricular, occipital, digastric, and stylohyoid muscles (Fig. 7-1, top). The main motor trunk of CN-VII then passes through the parotid gland to terminate as the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical branches. The first two innervate the muscles involved in moving the forehead, closing the eyes, and wrinkling the nose. Muscles of the lower face and neck are primarily innervated by the latter two branches. CN-VII subserves all muscles of facial expression except the levator palpebrae superioris and, therefore, CN-VII impairment, with a resultant asymmetric facies, is a major social and cosmetic impediment.

Clinical Correlations and Entities

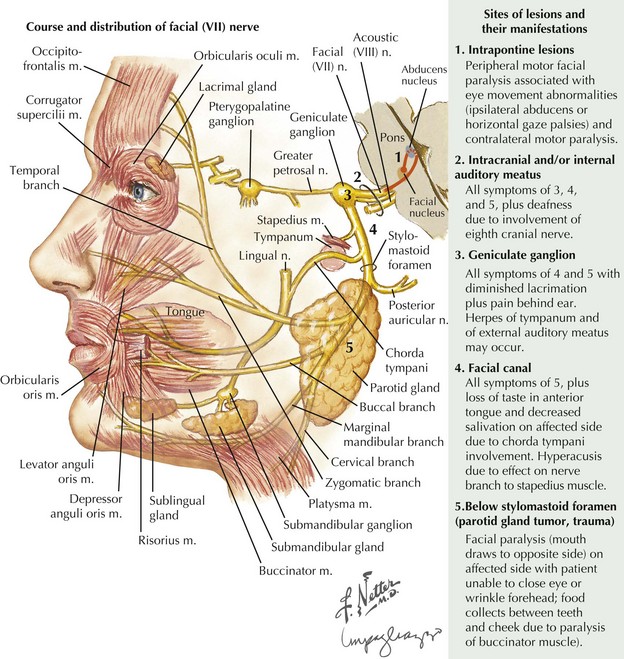

When intrapontine (Fig. 7-3, #1) lesions affect the facial motor nucleus per se, as well as its exiting fibers, involvement of neighboring brainstem structures is typically seen. The association of peripheral facial paralysis with ipsilateral conjugate gaze palsy (paramedian pontine reticular formation lesion), ipsilateral lateral rectus palsy (sixth cranial nerve lesion), or paresis of the opposite arm and leg (corticospinal tract lesion) usually indicates a pontine localization.

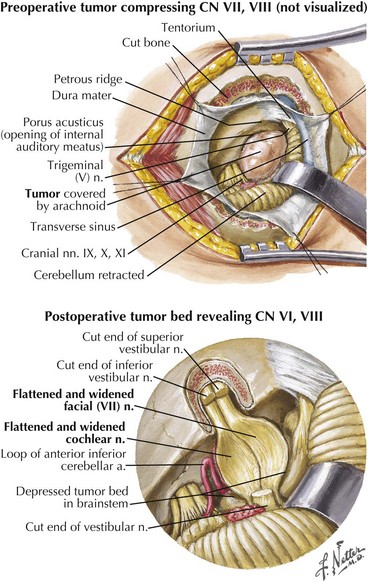

Extramedullary lesions (Fig. 7-3, #2) affecting the seventh nerve as it enters its intracranial course primarily occur within the cerebellopontine (CP) angle. Most commonly these are benign, relatively large acoustic neuromas that initially involve the eighth nerve and later extend to produce a seventh-nerve lesion. Thus, diminished hearing, sometimes initially presenting with tinnitus, usually precedes the onset of this type of peripheral facial paresis (see Fig. 7-4). Occasionally, with very large CP angle tumors there is concomitant involvement of the ipsilateral fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal nerve V) with unilateral facial numbness or initially only loss of the corneal reflex.

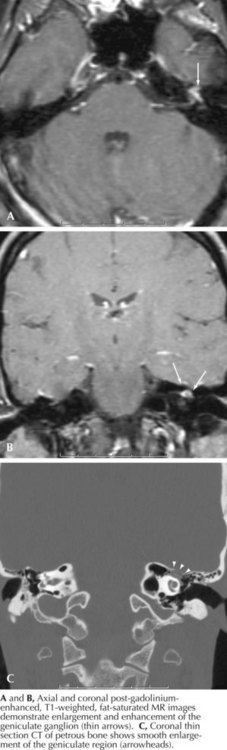

A relatively proximal pregeniculate, intracanicular facial nerve lesion (Fig. 7-3, #3) characteristically leads to diminished lacrimation from greater petrosal nerve involvement as well as hyperacusis (an increased sensitivity to sound that is particularly noticeable while using a telephone), due to associated stapedius muscle paresis. These lesions also lead to diminished salivation, absent or altered taste sensation for the anterior two thirds of the tongue, and affected somatic sensation for the external auditory canal.

When a facial nerve lesion is more distally situated, between the geniculate ganglion and the stapedius nerve all of the above findings occur, but lacrimation is spared as the greater petrosal nerve has already exited the geniculate ganglion. If damage occurs in the facial canal, involvement of the stapedius nerve and the chorda tympani (Fig. 7-3, #4) leads to hyperacusis and impaired salivation and taste but no change in lacrimation. When the seventh-nerve lesion is distal to the chorda tympani, it is characterized by a pure ipsilateral facial weakness (Fig. 7-3, # 5). Very rarely, a lesion of this type occurs after the facial nerve exits the skull through the stylomastoid foramen. On occasion, this can cause diagnostic difficulty early on as it may initially involve just individual motor branches, with limited weakness of individual facial muscles before a complete palsy develops. Facial trauma is the most common cause for acute pure motor CN-VII lesions; however, an insidious progressive course suggests that a parotid adenocarcinoma, as illustrated in the vignette on p. 98, is the most likely cause.

Clinical Vignette

Clinical Presentation

Facial asymmetry is unequivocally present; the affected frontalis is smooth and cannot be normally corrugated, whereas the angle of the mouth appears depressed even in repose. Inability to completely close the eyelids (lagophthalmos) results from orbicularis oculi weakness. The Bell phenomenon refers to the eyeball turning up without eyelid closure despite attempted contraction of the orbicularis oculi (Fig. 7-2). Facial palsy accompanied by taste disturbances may help to distinguish whether the lesion is proximal or distal to the chorda tympani branch. For example, a pure motor lesion suggests a lesion at the distal part of the facial canal or within the parotid gland, whereas when all four primary functions are affected, an unusually proximal lesion is deduced.

Differential Diagnosis

A slowly progressive evolution of a unilateral facial palsy most typically suggests the presence of a neoplasm. Pontine lesions, especially brainstem gliomas (Chapter 52), are the most proximal cause for a peripheral facial weakness. These tumors usually present in conjunction with other signs such as a lateral rectus palsy. Extramedullary tumors originating near the brainstem are often associated with facial nerve lesions and other cranial neuropathies, as with eighth-nerve acoustic neuromas or other cerebellopontine angle tumors (Fig. 7-4). When there is diffuse leptomeningeal involvement, such as with metastatic carcinoma or lymphoma, the facial nerves may be part of the initial clinical profile of infiltration with these malignancies. Eventually other and often multiple cranial nerves become involved, particularly the trigeminal, oculomotor, and optic nerves. As noted in vignette on p. 98, evolving, progressive, and purely motor facial palsies presenting with varying degrees of individual facial muscle involvement are classic for a parotid malignancy (Fig. 7-5).

Uncommon Mass Lesions

Cholesteatomas are rare mass lesions at the CP angle that deserve consideration in patients with slowly evolving facial paralysis. Other uncommon entities include pontine gliomas, arachnoid cysts, lipomas, and hemangiomas (Fig. 7-6).

Diagnostic Modalities

Imaging Studies

The two primary imaging options are MRI and CT. MRI is best at imaging the intracranial facial nerve, CP angle, and the parotid gland (Fig. 7-7). CT is the choice to image the temporal bone and its facial (fallopian) canal. MRI must include primary and gadolinium enhancement images. There may be unexpected relatively diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement when a facial neuropathy is the inciting lesion leading to a diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma or lymphoma.

Ang KL, Jones NS. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:386-388. Differential diagnosis of MRS is discussed

Finsterer J. Management of peripheral facial palsy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:743-752. This paper provides an excellent up-to-date review of idiopathic peripheral facial paralysis

Grose C, Bonthius D, Afifi AK. Chickenpox and the geniculate ganglion: facial nerve palsy, Ramsay Hunt syndrome and acyclovir treatment. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:615-617. This review suggests that facial palsy associated with VZV infection has poorer outcome than Bell palsy, and recommends the use of acyclovir

Keane JR. Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature. Neurology. 1994;44:1198-1202. Differential diagnosis of facial diplegia is discussed

Yanagihara N, Hato N, Murakami S, et al. Transmastoid decompression as a treatment of Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(3):282-286. In this study, 58 patients with severe palsy underwent transmastoid decompression after steroid treatment and had better outcomes compared to 43 patients treated conservatively