Chapter 18 Cranial and Facial Pain

Headache is an exceedingly common symptom that affects virtually everyone at some time in their life. It is estimated that nearly half of the world’s adult population has an active headache disorder (Robbins et al., 2010). Headache is one of the most common reasons for outpatient healthcare visits in the United States. Patients with head and/or face pain typically present for medical attention because the discomfort is severe, interferes with work and/or leisure activities, or raises the patient’s or family’s concern about a serious underlying cause.

Headache disorders are classified as primary or secondary (Box 18.1) (International Headache Society Classification Subcommittee, 2004). The primary headache disorders do not have an underlying structural cause, but all the primary headache disorders can be simulated by secondary conditions. The diagnosis of head and face pain depends on three elements: the history, neurological and general examinations, and appropriate investigations if needed. Treatment of headaches is discussed in Chapter 69.

Box 18.1

International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd Edition

The Secondary Headaches

Headache attributed to head and/or neck trauma

Headache attributed to cranial or cervical vascular disorder

Headache attributed to nonvascular intracranial disorder

Headache attributed to substance or its withdrawal

Headache attributed to infection

Headache attributed to disorder of homeostasis

Headache or facial pain attributed to disorder of cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth or other facial or cranial structures

Data from International Headache Society, 2003-2005.

History

The gold standard for diagnosis and management of headache is a careful interview and neurological and general medical examinations (De Luca and Bartleson, 2010). In the vast majority of patients with headache, the neurological and general examinations will be normal, so the diagnosis is based entirely on the history, and clinicians are well advised to spend most of their time interviewing the patient.

History-taking for head and face pain is similar to that for other presenting complaints, but several specific aspects should be addressed. The questions listed in Box 18.2 are useful, and the discussion that follows illustrates some responses and their implications. Usually one begins by asking the patient to describe their symptoms or, alternatively, simply by asking how they can be helped. This approach allows patients to relax and say what they had planned to say. Usually the patient will speak for less than 2 minutes if not interrupted (Langewitz et al., 2002). Once the patient has had an opportunity to speak, directed but open-ended questions (see Box 18.2) can be asked.

Box 18.2 Useful Questions to Ask the Patient with Headache

How many types of headache do you have?

How many types of headache do you have?

When and how did each type begin?

When and how did each type begin?

If the headaches are episodic, what is the frequency and duration?

If the headaches are episodic, what is the frequency and duration?

How long does it take for your headaches to reach maximal intensity?

How long does it take for your headaches to reach maximal intensity?

How long do your headaches last?

How long do your headaches last?

When do the headaches tend to occur, and what factors trigger your headaches?

When do the headaches tend to occur, and what factors trigger your headaches?

Where does your pain start, and how does it evolve?

Where does your pain start, and how does it evolve?

What is the quality and the severity of your pain?

What is the quality and the severity of your pain?

Is the pain steady or pulsating (throbbing), or both?

Is the pain steady or pulsating (throbbing), or both?

Are there symptoms that herald the onset of your headache?

Are there symptoms that herald the onset of your headache?

What are they, when do they begin, and how long do they last?

What are they, when do they begin, and how long do they last?

Are there symptoms that accompany your headaches?

Are there symptoms that accompany your headaches?

Do you get nauseated with your headaches?

Do you get nauseated with your headaches?

Does light and/or noise bother you a lot more when you have a headache than when you don’t?

Does light and/or noise bother you a lot more when you have a headache than when you don’t?

Do your headaches limit your ability to work, study, or do what you need to do for at least 1 day?

Do your headaches limit your ability to work, study, or do what you need to do for at least 1 day?

Does anything aggravate your pain (e.g., exertion)?

Does anything aggravate your pain (e.g., exertion)?

Are your headaches getting better or worse, or are they about the same?

Are your headaches getting better or worse, or are they about the same?

What treatments have been used to treat the headaches, both acutely and preventively?

What treatments have been used to treat the headaches, both acutely and preventively?

Is there a family history of headaches?

Is there a family history of headaches?

What prior testing have you had?

What prior testing have you had?

Do you have other medical or neurological problems?

Do you have other medical or neurological problems?

What do you think might be causing your headaches?

What do you think might be causing your headaches?

Onset of Headaches

A stable headache disorder of many years’ duration is almost always of benign origin. Migraine headaches often begin in childhood, adolescence, or early adulthood. A headache of recent onset obviously has many possible causes, including the new onset of either a benign or serious condition. “Recent onset” has been defined differently by various authors; the typical range is from 1 to 12 months. In general, the more recent the onset, the more worrisome. The “worst ever” headache, an increasingly severe headache, or change for the worse in an existing headache pattern all raise the possibility of an intracranial lesion. Headaches of instantaneous onset suggest an intracranial hemorrhage, usually in the subarachnoid space, but also can be caused by intracerebral hemorrhage, cerebral venous thrombosis, arterial dissection, pituitary apoplexy, spontaneous intracranial hypotension, benign angiopathy of the central nervous system (CNS), acute hypertensive crisis, and idiopathic primary thunderclap headache (Ju and Schwedt, 2010). Onset of a new headache in patients older than 50 years raises suspicion of an intracranial lesion (e.g., subdural hematoma) or giant cell (temporal or cranial) arteritis (GCA). A history of antecedent head or neck injury should be sought; even a relatively minor injury can be associated with subsequent development of epidural, subdural, subarachnoid, or intraparenchymal hemorrhage and posttraumatic dissection of the carotid or vertebral arteries (Dziewas et al., 2003). However, posttraumatic headaches can occur following head injury in the absence of any significant pathology.

Temporal Profile

A chronic daily headache without migrainous or autonomic features is likely to be a chronic tension-type headache. Untreated migraine pain usually peaks within 1 to 2 hours of onset and lasts 4 to 72 hours. Cluster headache is typically maximal immediately (if the patient awakens with the headache in progress) or peaks within minutes (if it begins while awake). Cluster headaches can last 15 to 180 minutes (usually 45 to 120 minutes). Headaches similar to cluster but lasting only 2 to 30 minutes and occurring several times a day are typical of episodic or chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, both of which are more common in women and are prevented by indomethacin (Goadsby et al., 2010). Primary stabbing headaches (“ice-pick pains”) are momentary, lasting only seconds. Stabbing pains are more common in patients with migraine and cluster headaches. Tension-type headaches commonly build up over hours and last hours to days to years. Headache that is daily and unremitting from onset, usually in patients without prior headaches, is classified as new daily-persistent headache and may have features suggestive of migraine or tension-type headache. A chronic, continuous, unilateral headache of moderate severity with superimposed attacks of more intense pain, associated with autonomic features, suggests the diagnosis of hemicrania continua, an indomethacin-responsive syndrome. Occipital neuralgia and trigeminal neuralgia manifest as brief shocklike pains, often triggered by stimulation in the territory served by the affected nerve. Occasionally a dull pain in the same nerve distribution persists longer, often after a series of brief, sharp pains. Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) is a rare syndrome consisting of paroxysms of first-division trigeminal nerve pain, lasting 5 to 240 seconds but occurring 3 to 200 times per day with the associated autonomic symptoms for which it is named (Goadsby et al., 2010)

Time of Day and Precipitating Factors

Cluster headaches often awaken patients from a sound sleep and may occur at the same time each day in an individual person. Hypnic headaches typically affect older patients and regularly awaken the patient at a particular time of night. Unlike cluster headaches, they are usually diffuse and not associated with autonomic phenomena (Donnet and Lanteri-Minet, 2009). Migraine headaches can occur at any time but often begin in the morning. A headache of recent onset that disturbs sleep or is worse on waking may be caused by increased intracranial pressure. Tension-type headaches typically are present during much of the day and often are more severe later in the day. Obstructive sleep apnea may be accompanied by the frequent occurrence of headache on awakening, as can medication-overuse headache (“rebound headache”).

Patients with chronic recurrent headaches often recognize factors that trigger an attack. Migraine headaches may be precipitated by bright light, menstruation, weather changes, caffeine withdrawal, fasting, alcohol (particularly beer and wine), sleeping more or less than usual, stress and release from stress, certain foods and food additives, perfume and smoke, and others. Alcohol can trigger a cluster headache within minutes of ingestion. If bending, lifting, coughing, or Valsalva maneuver brings on a headache, an intracranial lesion, especially one involving the posterior fossa, must be considered. Exertional headache and headache associated with sexual activity both are worrisome. Although either can occur as a primary headache disorder unassociated with structural disease or can be associated with migraine, both types can also be due to subarachnoid hemorrhage and arterial dissection, both of which must be excluded with the first occurrence of such headaches. Intermittent headaches that are worsened by sitting or standing and improved by lying down are characteristic of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. If there is no history of lumbar puncture, head trauma, or neurosurgical intervention, a spontaneous CSF leak may be the cause (Schievink, 2008). Lancinating face pain triggered by facial or intraoral stimuli occurs with trigeminal neuralgia. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia typically is triggered by chewing, swallowing, or talking, although cutaneous trigger zones in and about the ear are occasionally present.

Location

Migraine commonly is unilateral and can be confined to the front or back of the head. Alternatively, the pain can start on one side and spread to the other or be global from onset. Cluster headaches are unilateral during an attack and typically are centered in, behind, or around one eye. Some patients’ cluster headaches switch sides with different cluster periods, and a smaller number experience side shifts within a cluster period. The typical tension-type headache is generalized, although it may begin in the neck muscles and affect chiefly the occipital region or predominate frontally. When pain is localized to the eye, mouth, or ear, local processes involving these structures must be considered. Otalgia may be caused by a process involving the tonsil and posterior tongue. With chronic unilateral facial pain, an underlying lesion often cannot be identified. Occasionally, however, facial pain may be a symptom of nonmetastatic lung cancer (Eross et al., 2003).

Premonitory Symptoms, Aura, and Accompanying Symptoms

Symptoms originating from the brainstem or both cerebral hemispheres simultaneously, such as vertigo, dysarthria, ataxia, auditory symptoms, diplopia, bilateral visual symptoms in both eyes, bilateral paresthesias, and decreased level of consciousness, may accompany basilar-type migraine. Migraine with aura that includes motor weakness can be due to familial hemiplegic migraine if there is a family history in at least one first- or second-degree relative, or due to sporadic hemiplegic migraine if there is no family history. It can be difficult for the patient to differentiate sensory loss from true weakness. Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, and osmophobia characteristically accompany migraine attacks. In addition, lacrimation, rhinorrhea, and nasal congestion can accompany migraine headache and mimic headache of sinus origin (Cady et al., 2005). Ipsilateral miosis, ptosis, lacrimation, conjunctival injection, and nasal stuffiness commonly accompany cluster headache; sweating and facial flushing on the side of the pain are much less common. Similar autonomic features also accompany episodic and chronic paroxysmal hemicrania and hemicrania continua. Even shorter attacks (5–240 seconds) with ipsilateral conjunctival injection and tearing suggest SUNCT (Goadsby et al., 2010). Horner syndrome is common in carotid artery dissection. In the setting of acute transient or persistent monocular visual loss, GCA and carotid dissection should be considered. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction includes jaw pain precipitated or aggravated by movement of the jaw or clenching of the teeth and is associated with reduction in the range of jaw movement, joint clicking, and tenderness over the joint. Headache accompanied by fever suggests an infection. Headache associated with persistent or progressive diffuse or focal CNS symptoms, including seizures, implies a structural cause. Purulent or bloody nasal discharge suggests an acute sinus cause for the headache. Likewise, a red eye raises the possibility of an ocular process such as infection or acute glaucoma. A history of polymyalgia rheumatica, jaw claudication, or tenderness of the scalp arteries in an older person strongly suggests GCA. Transient visual obscurations upon standing, usually pulsatile tinnitus, diplopia (especially for objects in the distance), and papilledema may be associated with increased intracranial pressure from any cause, including idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri).

Disability

Baseline and follow-up assessment of headache-related disability is helpful in judging the effects of treatment and guiding headache therapy. The Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS) is one useful validated clinical tool (Andrasik et al., 2005).

Patient Concerns and Reasons for Seeking Help

The question of why the patient is seeking help may be obvious if the problem is of recent onset. If the problem is chronic, however, it can be useful to inquire why the patient has come for aid at this time. Red and yellow flags (see Box 18.3) help identify which patients are more likely to have a secondary cause of their pain.

Box 18.3

Headache Warning Flags

Red Flags

From De Luca, G.C., Bartleson, J.D., 2010. When and how to investigate the patient with headache. Semin. Neurol. 30, 133–134. Used with permission.

Other Medical or Neurological Problems

A history of past and current medical and neurological conditions, injuries, operations, and medication allergies should be obtained. A list of all current medications and dietary supplements should be recorded. A number of medications can cause headache, including hormonal, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal agents (De Luca and Bartleson, 2010).

Diagnostic Testing

In some situations, the diagnosis is uncertain, and additional diagnostic testing should be considered. The worrisome headache “warning flags” that increase the likelihood of a serious underlying intracranial process and often lead to additional testing are listed in Box 18.3. Red flags are more worrisome than yellow flags. Investigations for evaluation of the patient with headaches include almost all tests used in neurology and neurosurgery, as well as various medical studies. Selection of appropriate tests depends on the diagnostic formulation after the history and examination; indiscriminate use of batteries of tests is unwarranted.

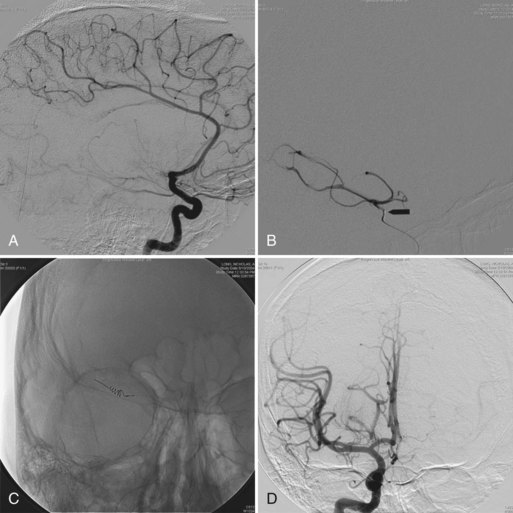

Neuroimaging and Other Imaging Studies

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are extremely useful tests in evaluating patients with headache. Tumors, hematomas, cerebral infarctions, abscesses, hydrocephalus, and many meningeal processes can be identified with CT and MRI. Abnormalities of the skull base, craniocervical junction, pituitary gland, meninges, and white matter are better seen with MRI. Advantages of CT over MRI include lower cost, a faster scan for those patients who either cannot remain still or are claustrophobic, compatibility with pacemakers and other implanted metal objects, and widespread availability. The iodinated contrast used in CT has been associated with allergic reactions and contrast-induced nephropathy. The contrast agent used in MRI is less likely to produce allergic reactions or renal damage, but it has been associated with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, typically in patients with preexisting renal impairment. The imaging modality of choice to investigate various causes of headache is shown in Box 18.4.

Box 18.4

Imaging Modality of Choice to Investigate Causes of Headache

Copyrighted and used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

CT can detect acute subarachnoid hemorrhage in at least 95% of patients if sufficient bleeding has occurred and the patient is scanned promptly. If findings on the CT scan are normal and the history is suggestive of recent subarachnoid hemorrhage, a lumbar puncture should be performed to assess for red blood cells and xanthochromia. CT can be helpful for evaluating abnormalities of the skull, orbit, sinuses, facial bones, and the bony cervical spine. Changes associated with intracranial hypotension are best shown with MRI and include enhancement of the pachymeninges, sagging of the brain, engorged veins, and subdural fluid collections (Schievink, 2008). The cervical spinal cord and exiting nerve roots are much better shown with MRI than with plain CT. Myelography with CT can be used to image the spine as an alternative to MRI. Magnetic resonance angiography is a noninvasive method that can demonstrate intracranial and extracranial vascular occlusive disease including large-vessel dissection, intracranial arteriovenous malformations, and aneurysms. CT angiography also can show arterial disease. Intracranial venous sinus thrombosis is best shown with magnetic resonance venography. For headache that is acute in onset or follows trauma, CT is the optimal imaging study to look for subarachnoid and other intracranial bleeding. For evaluation of patients with subacute and chronic headache, MRI is recommended (Sandrini et al., 2004). MRI is likely to reveal more than CT, but many of the abnormalities will be incidental, including asymptomatic cerebral infarctions, small aneurysms, and benign brain tumors (Vernooij et al., 2007).

Cerebrospinal Fluid Tests

CSF examination can diagnose or exclude meningitis, encephalitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and leptomeningeal cancer and lymphoma. It can also document increased or decreased intracranial pressure and confirm the diagnosis of “headache and neurological deficits with CSF lymphocytosis” (HaNDL) (Gomez-Aranda et al., 1997). Measurement of the opening CSF pressure should always be performed.

Electrophysiological Testing

Electroencephalography is not useful in the investigation of headache unless the patient also has a history of seizures, syncope, or episodes of altered awareness (Sandrini et al., 2004). There is no indication for use of evoked potentials in evaluating the patient with headache (Sandrini et al., 2004).

General Medical Tests

A few blood tests are important in the investigation of headache. Elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), often to 100 mm per hour or higher, is frequently seen in GCA. A normal ESR does not exclude the condition, because 4% of patients with positive findings on temporal artery biopsy have a normal ESR (Smetana et al., 2002). C-reactive protein and platelet count are also often elevated in patients with GCA. Rarely, episodic headaches associated with unusual behavior or impairment of consciousness can suggest an insulinoma, which is supported by elevated serum insulin and C-peptide levels in the face of a low or relatively low fasting glucose level. Levels of carboxyhemoglobin can be measured in patients complaining of early morning headaches during the home heating season, especially when several members of the same household are affected. Drug and alcohol screening may be helpful in certain patients. Thyroid function should be checked in patients with chronic headache, because hypothyroidism can present with headaches. Plasma and urine levels of catecholamines and metanephrines should be measured if a pheochromocytoma is suspected.

Rarely, cigarette smokers can present with face pain that includes the ear and is due to an underlying ipsilateral lung tumor without CNS involvement. Chest radiograph or CT of the chest can confirm the diagnosis (Eross et al., 2003).

Andrasik F., Lipchik G.L., McCrory D.C., et al. Outcome measurement in behavioral headache research: headache parameters and psychosocial outcomes. Headache. 2005;45:429-437.

Cady R.K., Dodick D.W., Levine H.L., et al. Sinus headache: a neurology, otolaryngology, allergy, and primary care consensus on diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:908-916.

De Luca G.C., Bartleson J.D. When and how to investigate the patient with headache. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:131-144.

Donnet A., Lanteri-Minet M. A consecutive series of 22 cases of hypnic headache in France. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:928-934.

Dziewas R., Konrad C., Dräger B., et al. Cervical artery dissection: clinical features, risk factors, therapy and outcomes in 126 patients. J Neurol. 2003;250:1179-1184.

Eross E.J., Dodick D.W., Swanson J.W., et al. A review of intractable facial pain secondary to underlying lung neoplasms. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:2-5.

Goadsby P.J., Cittadini E., Cohen A.S. Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias: paroxysmal hemicrania, SUNCT-SUNA, and hemicrania continua. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:186-191.

Gomez-Aranda F., Canadillas F., Marti-Masso J.F., et al. Pseudomigraine with temporary neurological symptoms and lymphocytic pleocytosis: a report of 50 cases. Brain. 1997;120:1105-1113.

International Headache Society Classification Subcommittee. International classification of headache disorders, second ed. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(1):1-160.

Ju Y.-E.S., Schwedt T.J. Abrupt-onset severe headaches. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:192-200.

Langewitz W., Denz M., Keller A., et al. Spontaneous talking time at start of consultation in outpatient clinic: cohort study. BMJ. 2002;325:682-683.

Robbins M.S., Lipton R.B. The epidemiology of primary headache disorders. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:107-119.

Sandrini G., Friberg L., Jänig W., et al. Neurophysiological tests and neuroimaging procedures in non-acute headache: guidelines and recommendations. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:217-224.

Schievink W.I. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:1345-1356.

Smetana G.W., Shmerling R.H. Does this patient have temporal arteritis? JAMA. 2002;287:92-101.

Vernooij M.W., Ikram M.A., Tanghe H.L., et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1821-1828.