Chapter 18 Cough

The Cough Reflex

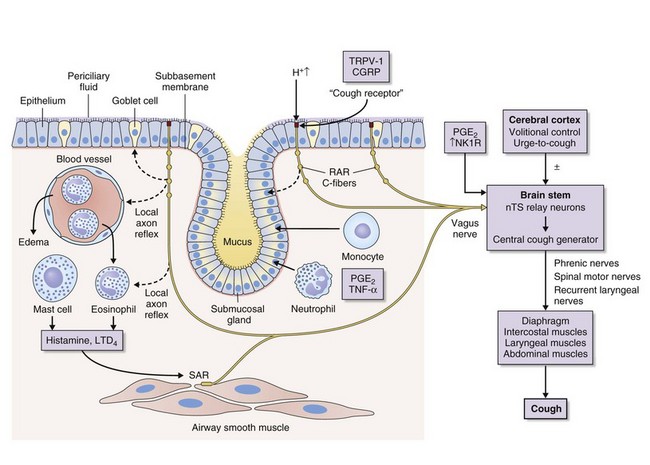

Cough is a reflex that occurs when afferent nerve receptors are stimulated by inhaled, aspirated, or endogenous substances. The most sensitive sites for initiating cough are the larynx, the carina, and the points of bronchial branching. Cough receptors also are present in extrapulmonary structures, including the esophagus, diaphragm, and stomach. A broad group of rapidly adapting “irritant” receptors (RARs) found in the larynx and tracheobronchial tree can be stimulated by a wide range of stimuli, including cigarette smoke, ammonia, ether vapor, acid and alkaline solutions, hypotonic and hypertonic saline, and mechanical stimulation by direct contact, mucus, or dust; all such stimuli can provoke cough. Another closely related fiber is the slowly adapting stretch receptor (SAR), which terminates inspiration and initiates expiration when the lungs are at an adequate level of inflation. SARs also may influence cough. C-fiber receptors, which have thin, nonmyelinated vagal afferent fibers, are found in the laryngeal, bronchial, and alveolar walls. They are relatively insensitive to mechanical stimulation and lung inflation but are exquisitely sensitive to chemicals such as bradykinin, capsaicin, prostaglandins, and acid pH. Stimuli that are known to cause cough in human subjects such as capsaicin, bradykinin, and citric acid activate C-fiber afferents, particularly those located in the bronchi. Afferent nerve fibers pass to a central cough receptor in the medulla, triggering a forced expiratory maneuver against a closed glottis, followed by glottal opening and high-velocity expiration (Figure 18-1).

Differential Diagnosis of Cough

The causes of cough can be conveniently divided into acute and chronic (Box 18-1 and Table 18-1). An acute cough is arbitrarily defined as a cough of less than 3 weeks’ duration. Infectious and allergic conditions are by far the most common etiologic disorders. Most acute coughs related to viral upper respiratory tract infection resolve by 3 weeks, but a small proportion become persistent and require further evaluation.

Most pulmonary conditions implicated in causing chronic cough, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, an inhaled foreign body, pulmonary tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and heart failure, will be obvious on clinical assessment, spirometry, and chest radiography. Assessment and management of these conditions are dealt with elsewhere in this book. Thus, a majority of patients referred for investigation of chronic cough are nonsmokers with normal findings on physical examination and chest radiography. Most present with a nonproductive or minimally productive cough, and 60% to 75% are female. A recognized tendency is for cough to manifest initially around the time of menopause. The most common conditions implicated in aggravating or causing chronic cough in these patients are listed in Table 18-1.

Table 18-1 Common Conditions Implicated in Causing Chronic Cough

| Diagnosis | Approximate Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Rhinitis | 25-30 |

| Asthma/eosinophilic bronchitis | 20-25 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 15-20 |

| Post–viral infection cough | 5-10 |

| Chronic bronchitis | 5-10 |

| Bronchiectasis | 5-10 |

| ACE inhibitor–induced cough | 5-10 |

| Unexplained | 5-20 |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Clinical Assessment

An initial assessment of a patient with chronic cough is directed at finding a specific cause, assessing severity, and initiating trials of treatment. A careful history and physical examination are paramount in the evaluation of a patient with chronic cough (Table 18-2). Details of the factors surrounding the onset of cough and associated symptoms and a careful assessment of the upper airways and the respiratory system are particularly important. Basic initial investigations should include up-to-date chest radiography, spirometry, and tests of bronchodilator reversibility, if appropriate. An abrupt onset of coughing while eating or chewing should raise the possibility of an inhaled foreign body, and the onset of cough shortly after introduction of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy suggests ACE inhibitor associated cough. The presence of significant quantities of sputum, hemoptysis, systemic symptoms, prominent breathlessness, wheeze, or abnormal physical signs increases the probability of intrinsic lung disease and should trigger appropriate investigations, which may include a CT scan of the chest and bronchoscopy even in the absence of suggestive findings with more simple investigations. The onset of cough with symptoms suggesting an upper or lower respiratory tract infection raises the possibility of a postinfectious cough; prominent whoops, a very troublesome nocturnal cough, and cough associated with vomiting all are associated with pertussis, a condition that is increasingly recognized in both school-age children and adults. Otherwise, little evidence is available to suggest that information on the timing, nature, complications, and potential aggravating factors is predictive of the underlying cause of the cough.

Table 18-2 Initial Evaluation of the Patient with Chronic Cough

| Evaluation Component | Assessment Factors |

|---|---|

| History | Cough: onset, duration, character, triggers, laryngeal paresthesia |

| Sputum: volume, character | |

| Smoking, occupation | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | |

| Drug history (ACE inhibitors) | |

| Asthma: breathlessness, wheeze, nocturnal symptoms, atopy | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux: reflux-associated symptoms | |

| Rhinitis: postnasal drip, sinusitis, throat clearing, nasal congestion | |

| Adverse quality of life: musculoskeletal chest pains, incontinence, syncope, social embarrassment, anxiety, disturbed sleep | |

| Snoring | |

| Examination | Clubbing |

| External nasal: polyps | |

| External ears: excessive wax | |

| Oropharyngeal: signs of postnasal drip, tonsillar enlargement | |

| Chest: signs of airflow obstruction, crackles | |

| Investigations | Chest radiograph |

| Spirometry ± bronchodilator reversibility | |

| Serial peak expiratory flow | |

| Complete blood count and eosinophil differential cell count | |

| Optional investigations | Bronchoprovocation challenge test, induced sputum, allergen skin tests |

| Exhaled nitric oxide test | |

| Sinus radiography/sinus CT study | |

| 24-hour esophageal pH and manometry | |

| Chest CT/bronchoscopy in selected patients | |

| Treatment for identified causes | Directed at cause(s) |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; CT, computed tomography.

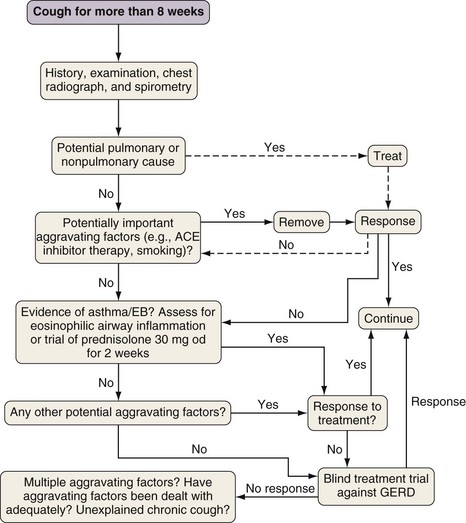

Findings on history and physical examination often are unremarkable, in which case the patient evaluation should focus on the recognition of corticosteroid-responsive conditions (i.e., asthma and eosinophilic bronchitis) and extrapulmonary factors that may be aggravating the cough, such as rhinitis and gastroesophageal reflux. One approach to the assessment of patients with chronic cough is outlined in Figure 18-2. The emphasis is on early recognition of corticosteroid-responsive cough, which can be detected easily in most cases with appropriate investigations or treatment trials. By contrast, the management of patients with nonasthmatic cough can be complex, time-consuming, and expensive, often with disappointing response to specific therapy. Far from clear, however, is whether extrapulmonary factors implicated in the pathogenesis of cough are aggravating a preexisting tendency or represent the underlying cause. Several factors point to the former, including the tendency for nonasthmatic chronic cough to affect middle-aged women and the frequent clinical observation that interventions against potential causes of chronic cough often help, but rarely cure the cough. It is best to have no preconceptions about the underlying causative factors in nonasthmatic cough and to view extrapulmonary factors such as rhinitis and gastroesophageal reflux as potential aggravating factors rather than as causes of the problem. This model has the advantage of providing a basis for the incomplete response to the treatment of these conditions seen in many patients; it also should stimulate research into the cause and treatment of the underlying heightened cough reflex sensitivity.

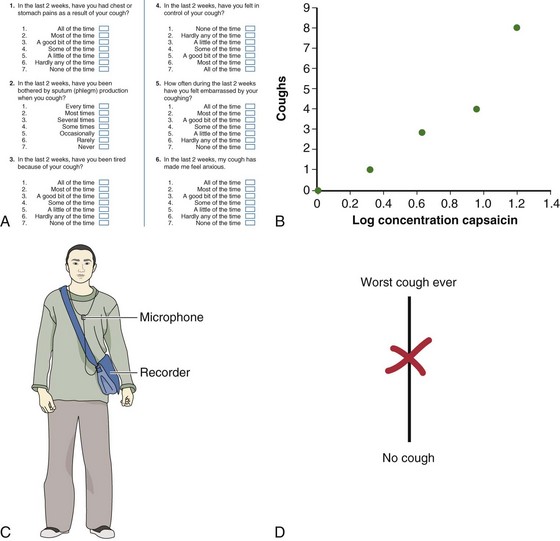

A further difficulty in evaluating patients with nonasthmatic chronic cough is the poor correlation between the presence of symptoms or abnormalities on investigation of the potential aggravating factor and the success of treatment directed against that factor. Thus, the diagnosis is secured largely by demonstrating clinical improvement as indicated by decrease in frequency or severity of cough after a suitable trial of treatment. Spontaneous improvement is common, and multiple potential aggravating factors typically are present; these factors add another layer of complexity to the clinical encounter. Results of treatment trials are more easily interpreted when combined with attempts to assess cough severity objectively before and after treatment. Suitable methods for such assessment include use of a simple cough visual analogue (with scores of 0 to 100 mm) (Figure 18-3), cough-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires, and evaluation of cough reflex sensitivity. A 15-mm change in visual analogue score, a 2-point change in Leicester Cough Questionnaire quality of life score, and a 2–doubling dose change in C2 (concentration of capsaicin that causes 2 coughs) can be regarded as evidence of a significant response to treatment. The remainder of this section focuses on the evaluation of the commoner conditions implicated in causing chronic cough.

Cough Variant Asthma/Eosinophilic Bronchitis

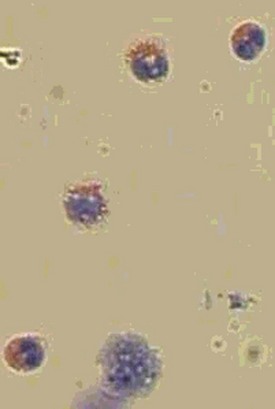

Eosinophilic bronchitis is an increasingly recognized entity that presents with a corticosteroid responsive cough and is characterized by sputum eosinophilia (Figure 18-4), heightened cough reflex sensitivity, but no evidence of variable airflow obstruction or airway hyperresponsiveness. Most patients also have a raised exhaled nitric oxide concentration, and blood eosinophilia often is present. Studies suggest that eosinophilic bronchitis is responsible for 10% to 15% of cases of chronic cough. The airway inflammation is similar to that seen in asthma although available evidence indicates that differences in the pattern of airway dysfunction are due to differences in the site of mast cell localization within the airway, with infiltration of the epithelium occurring in eosinophilic bronchitis and infiltration of the airway wall smooth muscle occurring in asthma. Recognition of eosinophilic bronchitis is important, because like cough variant asthma, it responds well to inhaled corticosteroids. This is best achieved by assessing airway inflammation using induced sputum or exhaled nitric oxide; if these techniques are not available, a trial of corticosteroid therapy is indicated irrespective of the presence of airway hyperresponsiveness.

Treatment

Treatment directed at the specific cause of chronic cough is summarized in Table 18-3. With use of the anatomic diagnostic protocol, success rates of up to 95% in the management of chronic cough have been reported. The success rate goes down to 60% to 80% in specialist cough clinics, possibly owing to the complexity of cases referred. Reassessment of the patient after treatment with exclusion of additional aggravating factors or causes forms an integral part of management for chronic cough. A common dilemma faced by physicians managing these patients is that the diagnosis of cough often depends on successful trials of treatment, which if unsuccessful leads to the difficult question of whether the underlying condition has not responded or is not responsible for the cough. In some situations, the use of objective tests to make a diagnosis and careful validation of the effect of therapy for the underlying condition should minimize this problem. Therapeutic interventions for common causes of chronic cough are discussed next.

| Cause | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Rhinitis | Nasal corticosteroids |

| Selected patients: topical ipratropium, topical decongestants, oral antihistamines, surgery | |

| Asthma | Inhaled corticosteroids |

| Leukotriene antagonists | |

| Eosinophilic bronchitis | Inhaled corticosteroids, oral corticosteroids in selected cases |

| GER-associated cough | Self-help measures: weight loss, smoking cessation, reduce alcohol intake, elevate head of bed, avoid eating within 2 hours of bedtime |

| Acid suppression: proton pump inhibitors | |

| Prokinetic agents: metoclopramide or domperidone in selected patients | |

| Surgery: laparoscopic fundoplication in selected patients | |

| Chronic bronchitis | Smoking cessation |

| ACE cough | Drug withdrawal; substitution of alternative if appropriate |

| Post–viral infection cough | Observation |

| Bronchiectasis | Chest physiotherapy and postural drainage, antibiotics |

| Idiopathic chronic cough | Antitussives (dextromethorphan, codeine); nebulized lidocaine; speech and language therapy or physiotherapy |

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; GER, gastroesophageal reflux.

Unexplained Chronic Cough

Unexplained cough is responsible for considerable physical and psychological morbidity. Many patients with unexplained chronic cough are labeled with a diagnosis of psychogenic cough, although little evidence is available to support this view, and it is perhaps more likely that any abnormal illness behavior is secondary to the adverse impact of cough on psychosocial aspects of quality of life. In evaluating a patient with unexplained cough, it is important to recognize common pitfalls in managing chronic cough (Box 18-2). Therapy for idiopathic chronic cough is disappointing, and there is therefore a large unmet need for better antitussive treatment in these patients. Referral to a respiratory physiotherapist or speech therapist for cough management coaching may be of some help.

Box 18-2

Common Pitfalls in the Management of Chronic Cough

Failure to recognize multiple causes of cough

Failure to recognize multiple causes of cough

Lack of objective evidence for the diagnosis of asthma

Lack of objective evidence for the diagnosis of asthma

Prolonged and aggressive treatment may be required before cough improves.

Prolonged and aggressive treatment may be required before cough improves.

Post–viral infection and gastroesophageal reflux–associated cough may take many months to resolve.

Post–viral infection and gastroesophageal reflux–associated cough may take many months to resolve.

American College of Chest Physicians. http://chestjournal.chestpubs.org/content/129/1_suppl/1S.full. (cough guideline summary)

British Thoracic Society. http://www.britthoracic.org.uk/Portals/0/Clinical%20Information/Cough/Guidelines/coughguidelinesaugust06.pdf. (cough guidelines)

International Society for the Study of Cough. http://www.issc.info.

Birring SS. Controversies in the evaluation and management of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:708–715.

Birring SS, Berry M, Brightling CE, Pavord ID. Eosinophilic bronchitis: clinical features, management and pathogenesis. Am J Respir Med. 2003;2:169–173.

Birring SS, Brightling CE, Symon FA, et al. Idiopathic chronic cough: association with organ specific autoimmune disease and bronchoalveolar lymphocytosis. Thorax. 2003;58:1066–1071.

Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, et al. Development of symptom specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax. 2003;58:339–343.

Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis and causes of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371:1364–1374.

Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):1S–23S.

Irwin RS, Madison JM. The diagnosis and treatment of cough. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1715–1721.

Morice AH, Fontana GA, Belvisi MG, et al. ERS guidelines on the assessment of cough. Eur Respir J. 2007;29:1256–1276.

Morice AH, McGarvey L. Pavord I, for the British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group: Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. Thorax. 2006;61(Suppl 1):i1–i24.

Pavord ID, Chung KF. Management of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371:1375–1384.