Chapter 21 Cosmeceuticals and Contact Dermatitis

VITAMINS

Contact dermatitis to cosmeceutical vitamins such as vitamin A (retinol), vitamin C (ascorbic acid), and vitamin E (tocopherol) has been reported in the literature. Vitamin A and its derivatives such as retinol, retinaldehyde, and retinyl palmitate typically produce an irritant contact dermatitis with dryness and skin irritation. This irritation is an unwanted side effect of retinization of the face, but cannot be avoided if the beneficial collagen regenerative effects are to be experienced. Irritant contact dermatitis can sometimes present identically to allergic contact dermatitis, but vesiculation and facial swelling are never an expected part of early retinization of the face. Allergic contact dermatitis to vitamin A is rare, but can be confirmed by positive patch testing. The vitamin A-containing cream can be closed patch tested ‘as is’, but many times it is impossible to determine which of the many ingredients in the preparation is the culprit. Most large cosmeceutical manufacturers can provide a sample of the vitamin A raw material they use in their formulation for individual ingredient patch testing. The person to contact at the company and the address can be obtained from the Cosmetic Industry On Call brochure published as a joint effort between the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) and the Personal Care Products Council (PCPC; formerly the Cosmetic, Toiletry, and Fragrance Association). More information can be obtained at the PCPC website at http://www.personalcarecouncil.org.

Vitamin E, part of a family of compounds called tocopherols, is a common cause of both irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Its role as a contact allergen is well documented, thus vitamin E represents the most common cosmeceutical vitamin to cause allergic contact dermatitis. Some of the reports have dealt with allergic reactions experienced to vitamin E found in a line of colored cosmetics manufactured in Europe. It appears that the manufacturer used food grade vitamin E instead of cosmetic grade vitamin E which accounted for the allergic contact dermatitis. Many of the casually reported cases of vitamin E allergy appear to be due to consumers breaking open vitamin E capsules intended for oral consumption and rubbing the oil onto wounds or scars to promote healing. While vitamin E formulated in this manner is safe for human oral consumption, it is not intended for topical application. Cosmetic grade vitamin E properly formulated in a moisturizing cream is rarely allergenic.

BOTANICALS

Aloe is a commonly used botanical extract for its soothing properties on wounds, burns, and irritated skin (Fig. 21.1). It is a mucilage containing thousands of individual chemical entities. This makes determination of the exact allergen impossible. Yet, case reports of allergic contact dermatitis are found in the literature. Patients who have experienced a suspected allergic contact dermatitis to aloe should simply learn to read ingredient labels and avoid products containing this botanical extract. It is not hard to avoid cosmeceuticals containing aloe.

Tea tree oil or melaleuca oil is derived from the Cheel shrub in Australia (Fig. 21.2). It has gained increasing popularity in a variety of over-the-counter (OTC) products, including antibacterials, antifungals, shampoos, and OTC salon treatment products designed to minimize dandruff or seborrheic dermatitis. Tea tree oil can cause allergic contact dermatitis and in one study was found to be the most allergenic botanical extract. Although there are several antigenic components of this oil, the constituents of the oil thought to cause the majority of allergic reactions are d-limonene and terpinen-4-ol; however, not all patients who react to tea tree oil react to these components.

The Compositae family comprises a group of plants that have sensitizing capabilities. Arnica montana is an important medicinal plant that has been reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis (Fig. 21.3). Screening patients with sesquiterpene lactone mix, found on the traditional dermatologic patch test tray, may miss some of these reactions and therefore testing to the plant or other chemical constituents of the plant is recommended. Chamomile, another member of the Compositae family, is also a cause of allergic contact dermatitis (Fig. 21.4). This is interesting given the fact that a chamomile extract, known as bisabolol, is used as an anti-inflammatory in cosmeceutical moisturizers. However, echinacea and marigold are two members of this family that have not been reported to cause allergic contact dermatitis. This indicates that there must be subtle differences in each of these plant extracts accounting for the presence or absence of the dermatitis-causing allergen.

Patch testing for botanical allergens is difficult as standardized allergens for these newer compounds are not readily available. Furthermore, screening allergens are not adequate to indicate the possibility of botanical allergy. In a study of those with known botanical allergy, fragrance mix was positive in only 33.3% of patients, balsam of Peru in 30%, Compositae mix in 20%, and sesquiterpene lactone in only 6.7%. Therefore, in those suspected of contact allergy, if a botanical is being used, testing to the individual botanical is recommended.

FRAGRANCES

Many cosmeceutical products are fragranced and an allergic or irritant reaction may be due to the fragrance component. Fragrances are the most common cause of allergic contact dermatitis to cosmetics. Patch testing to fragrance is typically done via a fragrance mix that contains the individual fragrance ingredients listed in Box 21.1.

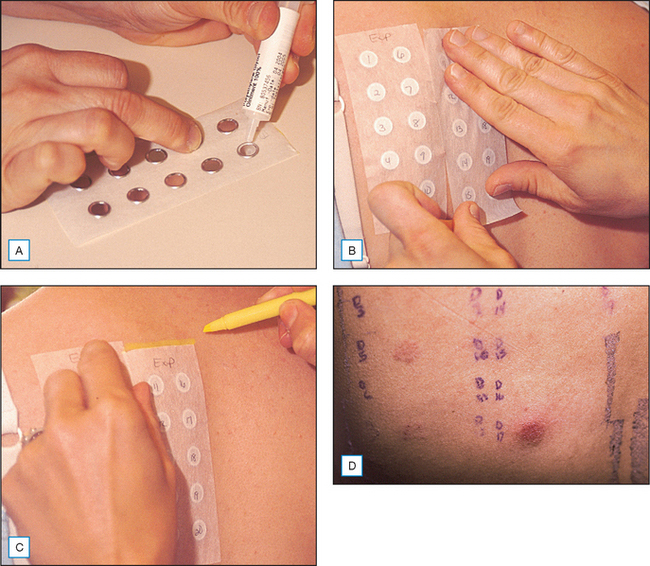

PATCH TESTING

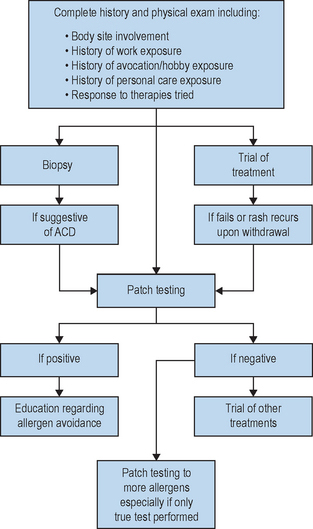

The gold standard for diagnosing an allergic contact dermatitis to any product including cosmeceuticals is patch testing. This is a simple easy office procedure that can be extremely helpful in determining the cause of a patient’s dermatitis (Fig. 21.5). Obviously, other causes of the patient’s reaction including irritant contact dermatitis, contact urticaria, acneiform eruptions, rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, perioral dermatitis, and other skin disorders must be considered. However, in the patient who does not respond to traditional methods of treatment, or who has a persistent or localized dermatitis, or a dermatitis that flares after discontinuation of a treatment regimen, the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis should be considered and patch testing should be performed. It is important to note that most patients, and even experienced specialists within the field of allergic contact dermatitis, are unable to reliably and consistently identify the causative allergen prior to patch testing based on history and physical examination alone.

Once the allergens to be tested have been chosen, a nurse within the office, who has been trained on the application of patch testing, applies the patches. This involves applying allergens to the upper back and taping them in place. The allergens applied can be obtained from several different companies including Allerderm (manufacturers of TRUE Test, Petaluma, CA, US), Chemotechnique Diagnostics (Malmo, Sweden), Trolab/Pharmascience (Montreal, Canada) and Smart Practice (manufacturers of AllergEAZE, Calgary, Canada). The TRUE Test is a reasonable starting place for patch testing but studies have shown that expanded sets of allergens are more successful in identifying a causative allergen in the patient who suffers from allergic contact dermatitis. Therefore, if considering the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, expanded testing is often helpful, particularly if the TRUE Test is unrevealing. If expanded allergen series are not available, referral to a center specializing in patch testing may be necessary if the suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis remains. It is usually possible to obtain the specialized allergens required by contacting the company as listed in the Cosmetic Industry On Call brochure. Most companies can also provide information on how to formulate and apply the patches, as well as providing the Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) for specific chemical information about the substance.

The initial patches should be kept in place and kept dry for 48 hours. The patches are then removed and a map of the allergens is drawn on the back. The patient should return for a second reading from 96 hours to 1 week later to assess for delayed reactions which are well documented in the literature. If a second reading is not performed, several allergic reactions may be missed (Box 21.2).

Box 21.2 Responses in patch test reading

| 1/− | + macular erythema only |

| + | = weak (nonvesicular) reaction; erythema, infiltration, possibly papules |

| ++ | = strong (edematous or vesicular) reaction |

| +++ | = extreme (spreading, bullous or ulcerative) reaction |

| IRR | = irritant morphologic appearance |

| − | = negative reaction |

| NT | = non tested |

As many of the cosmeceuticals are relatively new and standardized allergens are not available, testing to the products themselves can be helpful. If the product is intended to be a leave-on product, it can be tested as is. However, if the product is a rinse-off product intended to be diluted with water, the product must be diluted prior to application so as to avoid irritant reactions. There are guides available to help determine the appropriate dilutions of such products. Controls must be done when using patient products for testing. The standard negative control used is generally petrolatum. It may also be worthwhile to include a positive irritant, such as sodium lauryl sulfate, if an irritant reaction is suspected for comparison.

If an allergic reaction is identified, the patient should be instructed on allergen avoidance, and label reading. The dermatitis can take 6–8 weeks to resolve despite avoidance and patients should be reassured during this time period. A database called the Contact Allergen Replacement Database is available to members of the American Contact Dermatitis Society through the society web page (http://www.contactderm.org) and can be very helpful in identifying products free of a patient’s known allergens. In this member-only database, the physician enters the chemicals to which the patient tested positive and the database provides a listing of products free of these chemical ingredients. The database is extensive but is limited by the products entered into the database. It is updated once yearly. It can prove helpful in identifying products a patient can use and is a helpful resource for patients.

Cosmeceuticals are an increasingly popular arena in the skin care market. Even these products, many containing natural ingredients and intended to enhance beauty, can cause an allergic or irritant contact dermatitis. Contact dermatitis to these products has been reported though not with high frequency. As more people use cosmeceuticals, an increase in adverse reactions might be expected. Fortunately, the cosmetic industry is early to recognize problems and reformulate to minimize consumer difficulties. Nevertheless, the possibility of allergic contact dermatitis should be considered. Patch testing is an important tool to identify and confirm the possible cause of an adverse reaction to a cosmeceutical (Fig. 21.6).

Bazzano C, De Angeles S, Kleist G, Maedo N. Allergic contact dermatitis from topical vitamins A and E. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:261–262.

De Groot AC. Patch testing, 2nd edn. New York: Elsevier, 1994.

De Groot AC. Fatal attractiveness: the shady side of cosmetics. Clinics in Dermatology. 1998;16:167–179.

Frosch PJ, Johansen JD, Menne T, Pirker C, Rastogi SC, Andersen KE. Further important sensitizers in patients sensitive to fragrances. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:279–287.

Hughes T, Stone N. Benzophenone 4: an emerging allergen in cosmetics and toiletries? Contact Dermatitis. 2007;56:153–156.

Kiken D, Cohen D. Contact dermatitis to botanical extracts. American Journal of Contact Dermatitis. 2002;13:148–152.

Kim B, Lee Y, Kang K. The mechanism of retinal-induced irritation and its application to anti-irritant development. Toxicology Letters. 2003;146:65–73.

Mowad C. Patch testing for cosmetic allergens. Atlas of Office Procedures. 2001;4:551–563.

Paulsen E. Contact sensitization from Compositae-containing herbal remedies and cosmetics. Contact Dermatitis. 2002;47:189–198.

Pratt MD, Belsito DV, Deleo VA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch-test results, 2001–2002 study period. Dermatitis. 2004;15:176–183.

Scheinman P. Exposing covert fragrance chemicals. American Journal of Contact Dermatitis. 2001;12:225–228.

Scheman A. Adverse reactions to cosmetic ingredients. Dermatologic Clinics. 2000;18:685–698.

Scheuer E, Warshaw E. Sunscreen allergy: a review of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and responsible allergens. Dermatitis. 2006;17:3–11.

Simpson EL, Law SV, Storrs FJ. Prevalence of botanical extract allergy in patients with contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2004;15:67–72.

Thomson K, Wilkinson S. Allergic contact dermatitis to plant extracts in patients with cosmetic dermatitis. British Journal of Dermatology. 2000;142:84–88.

Thornfeldt C. Cosmeceuticals containing herbs: fact, fiction and future. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31:873–880.

Wolf R, Wolf D, Tuzun B, Tuzun Y. Contact dermatitis to cosmetics. Clinics in Dermatology. 2001;19:502–515.