Chapter 12 Cosmeceutical Botanicals: Part 2

INTRODUCTION

The explosive growth of the cosmeceutical industry has resulted in the introduction of many new ‘active’ ingredients. Most are derived from nature for unique marketing stories and to reduce the risk of federal oversight. About 100 different ingredients derived from plant sources are being incorporated into cosmeceutical and skin care products. It behooves all physicians and skincare providers recommending cosmeceuticals to have a working knowledge of botanicals so the best recommendations can be made to patients and clients.

complete characterization of the huge number of active compounds in a single plant source

complete characterization of the huge number of active compounds in a single plant source

documenting the activity and interaction of each of these compounds and their many metabolites

documenting the activity and interaction of each of these compounds and their many metabolites

understanding the therapeutic synergy of these active components within the single plant and between multiple plants

understanding the therapeutic synergy of these active components within the single plant and between multiple plants

discovering how the potential toxicity of specific compounds is modified by using an entire plant or an anatomic structure of the plant—for example, the castor bean is the source of ricin, one of the most poisonous compounds known to man, and azelaic acid, a nontoxic prescription dermatologic medicine.

discovering how the potential toxicity of specific compounds is modified by using an entire plant or an anatomic structure of the plant—for example, the castor bean is the source of ricin, one of the most poisonous compounds known to man, and azelaic acid, a nontoxic prescription dermatologic medicine.

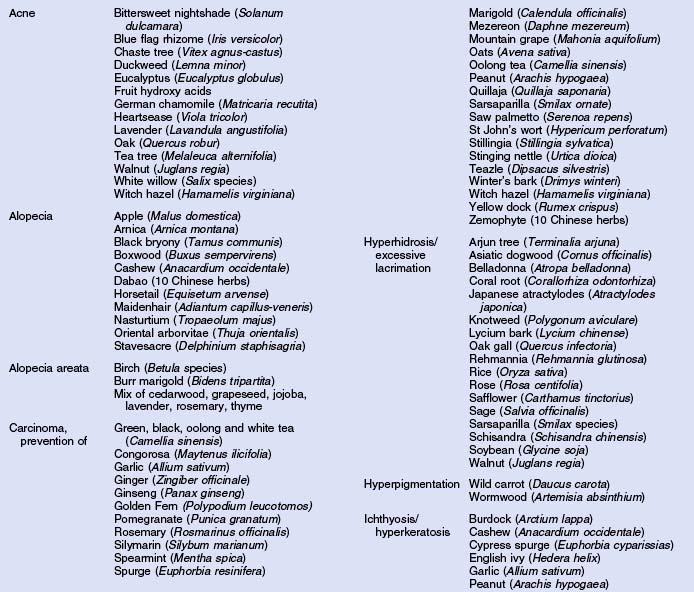

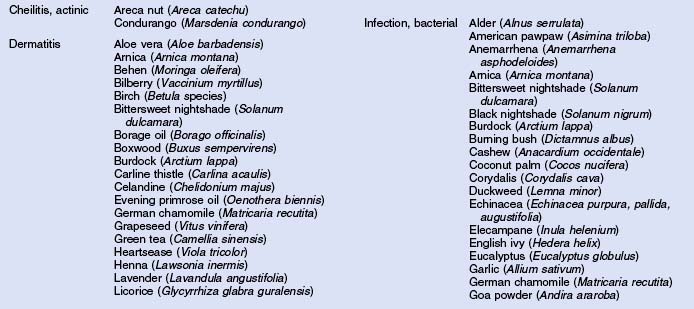

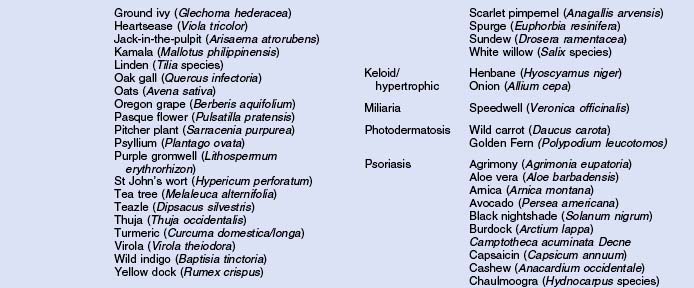

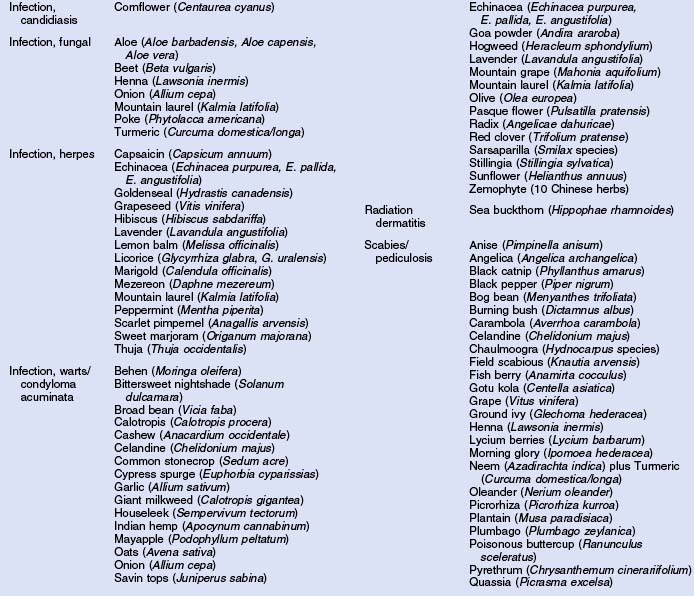

Herbs with mucocutaneous therapeutic indications as determined by Commission E and PhytoPharm are listed in Table 12.1. The first group of herbs discussed below consists of most of the top 12 largest selling herbs in the US based on dollar volume. Of all the herbs listed with mucocutaneous applications, only 27 have been supported by reliable double-blind or open label clinical trials as listed in Table 12.2. The second group consists of most of the 21 herbs formulated into products tested in blinded clinical trials for treatment of photoaging as listed in Table 12.3.

Table 12.2 Herbs with clinical trials for treatment of mucocutaneous diseases/conditions

|

|

Table 12.3 Herbs with clinical trials for photoaging therapy

|

|

LARGEST SELLING HERBS

• Echinacea (Fig 12.1)

Fig. 12.1 Topical and oral Echinacea is an antioxidant. Echinacea is rich in caffeic and ferulic acids

All three Echinacea species stimulate immunity, protect type III collagen, and have antioxidant activity, thus photoaging therapy is promising (Tables 12.1, 12.2). They are also cytotoxic to multiple bacteria and viruses.

• Garlic

Garlic’s antibacterial activity is against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria with potency comparable to many prescription antibiotics. Its antiyeast activity is comparable to nystatin while its activity against dermatophytes is superior to seven marketed antifungals. Garlic inhibits herpes hominis I. It effectively treated warts in a 32-patient clinical study using a lipid extract, producing complete clearing in 2 weeks (Tables 12.1, 12.2). Aged garlic appears promising in treating photoaging due to its inhibition of glycation end products.

• Saw palmetto (Fig. 12.2)

The major components of saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) include sterols, glucosides, flavonoids, free fatty acids, and polysaccharides. This herb has documented anti-androgenic, anti-estrogenic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-exudative effects. It is a remedy for dermatitis, mucositis, and alopecia in folk medicine (Tables 12.1, 12.2).

• Ginseng (Fig. 12.3)

Ginseng species have potential as treatments for photoaging. In vitro, Panax ginseng stimulated fibroblast type I collagen synthesis. Ginsenosides in vivo inhibited cyclooxygenase-2, nuclear factor kappa B, activating protein-1, and melanogenesis. Hyaluronan and epidermal growth factor synthesis were stimulated as was matrix metalloproteinase I. Thus a product containing any ginsengs must have a clinical trial with the marketed formulation to prove efficacy for photoaging.

Hair growth was stimulated with topical ginseng in an open clinical trial.

Cases of vaginal bleeding from a topical face cream are a very rarely reported adverse reaction, as is death (Tables 12.1, 12.2).

• St John’s wort (Fig. 12.4)

Fig. 12.4 St John’s wort contains the anti-inflammatory quercetin. It is used to enhance wound healing

This herb’s actives include flavonoids, and oligomeric procyanidins (OPCs), xanthones, acylphloroglucinols, volatile oils, caffeic acid derivatives, and anthracenes including hypericin. The major adverse reactions include death, photosensitivity and radiation recall dermatitis (Tables 12.1, 12.2).

• Teas: white, black, oolong

Black tea has one-sixth the content of catechins than green tea, but has a higher content of other flavonoids such as quercetin, polyphenols, and saponins. Black tea inhibits cutaneous photodamage, squamous cell carcinogenesis, and inflammation. Oral administration of black and oolong teas, like green tea, have been found to suppress both type I and type IV hypersensitivity reactions (Tables 12.1, 12.2). Ingested oolong tea helped clear atopic dermatitis.

• Tea tree

This essential oil from Melaleuca alternifolia is being used throughout American society to treat and prevent a variety of mucocutaneous conditions. Tea tree oil (TTO) consists primarily of terpenes including terpinen, the major sensitizer. It passed nickel as the most common contact allergen in 2005. TTO does not have antioxidant activity.

TTO is cytotoxic to epithelial cells and fibroblasts, and thus should not be used to treat burns. TTO is a strong photosensitizer, indicating caution with use in products for sun-exposed skin such as the face (Tables 12.1, 12.2).

• Lavender (Fig. 12.5)

Lavender oil is therapeutic for insect bites, burns, wounds, lacerations, acne, psoriasis, herpes, and fungal infections. A double-blinded clinical trial treating alopecia areata with a mixture of five other botanical oils produced a significant improvement in hair regrowth after 7 months (Tables 12.1, 12.2). In a 40-panelist open clinical trial using lavender in an aromatherapy bath, anger/frustration levels were significantly reduced.

• Pomegranate

This herb has antimutagenic and chemopreventive activity. Pomegranate for photoaging therapy is promising due to inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase I and stimulation of type I collagen in vivo. In a double-blind clinical trial of 13 females, oral pomegranate statistically significantly reduced UVB-induced slight sunburn and slight hyperpigmentation.

HERBS IN PHOTOAGING CLINICAL TRIALS

There is a paucity of human clinical trials using topically applied herbal formulations to treat photoaging. Twenty herbal ingredients have been used in these studies (Table 12.3). Only seven were solitary actives in double-blind trials including green tea, soy (total), date palm, licorice, oat, tamarind and coffeeberry.

SUMMARY

Numerous plant-sourced ingredients are being added into cosmeceutical formulations as ‘active’ ingredients. Unfortunately, they have multiple variables that affect formulation integrity and clinical activity and safety. Only 20 herbs have been used in topical formulations treating photoaging in human clinical trials. When treatment of all skin diseases and conditions is administered topically or orally, another 27 herbs have been evaluated in human clinical trials.

Ahmad MS, Pischetsrieder M, Ahmed N. Aged garlic extract and S-allyl cysteine prevent formation of advanced glycation endproducts. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;561:32–38.

Auerbach PS. Wilderness medicine, 4th edn., St Louis: Mosby; 2001:411. 1133, 1170, 1176, 1177

Baumann LS. Cosmeceutical critique: tea tree oil. Skin and Allergy News. 2002 November:14.

Baumann LS. Cosmeceutical critique: chamomile. Skin and Allergy News. 2003 July:43.

Baumann LS. Cosmeceutical critique: lavender. Skin and Allergy News. 2003 September:33.

Baumann LS. Cosmeceutical critique: grape seed extract. Skin and Allergy News. 2003 November:26.

Baumann LS. Cosmeceutical critique: pomegranate. Skin and Allergy News. 2004 January:42.

Baumann LS. Cosmeceutical critique: ginseng. Skin and Allergy News. 2006 October:18.

Bauza E, Dal Farra C, Berghi A, Oberto G, Peyronel D, Domloge N. Date palm kernel extract exhibits antiaging properties and significantly reduces wrinkles. International Journal of Tissue Reactions. 2002;24:131–136.

Bedi MK, Shenefelt PD. Herbal therapy in dermatology. Archives of Dermatology. 2002;138:232–242.

Blake J 2002 Tea for you. Life section. In: The Idaho Statesman February 22:1

Dehghani F, Merat A, Panjehshahin MR, Handjani F. Healing effects of garlic extracts on warts and corns. International Journal of Dermatology. 2005;44:612–615.

Hsu S. Green tea linked to skin cell rejuvenation. ScienceDaily April 25. Online. Available: www.science-daily.com, 2003.

Jancin B. Novel antioxidant shows promise as photoaging topical. Skin and Allergy News April. 2007;1:34.

Jellin JM, Gregory P, Batz F, et al. Natural medicines comprehensive database, 8th edn., Stockton, CA: Therapeutic Research Facility; 2006:149-151. 165–170, 456–459, 558–561, 566–568, 580–590, 620, 621, 634–640, 793–794, 891–892, 1015–1017, 1115–1117, 1172–1179, 1219, 1220, 1336–1338

Kasai K, Yoshimura M, Koga T, Arii M, Kawasaki S. Effects of oral administration of ellagic acid-rich pomegranate extract on ultraviolet induced pigmentation in human skin. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology. 2006;52:383–388.

LaGow B, editor. PDR for herbal medicines, 3rd edn. Montvale, NJ: Thomson PDR. 2004:93-97. 267–274, 285–288, 344–353, 354–359, 379–387, 400–404, 408–413, 592–593, 650, 651, 707–710, 767–786, 817–821, 875–876

Lee J, Jung E, Lee J, et al. Panax ginseng induces type I collagen synthesis through activation of small signaling. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;109:29–34.

Levin C, Maibach H. Exploration of ‘alternative’ and ‘natural’ drugs in dermatology. Archives of Dermatology. 2002;138:207–211.

Norman R, Nelson D. Do alternative and complementary therapies work for common dermatologic conditions? Skin and Aging. 2000;2:28–33.

Pajonk F, Riedisser A, Henke M, McBride WH, Fiebich B. The effects of tea extracts on proinflammatory signaling. BMC Med, 4. 2006:28-39. Online. Available: www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov.

Putnik K, Stadler P, Schäfer C, Koelbl O. Enhanced radiation sensitivity and radiation recall dermatitis (RRD) after hypericin therapy: case report and review of literature. Radiation Oncology. 2006;1:32–40.

Thornfeldt C. Science or spin. Healthy Aging. 2006;2:55–62.

Winston D, Dattner A. The American system of medicine. Clinics in Dermatology. 1999;17:53–55.

Yarnell E, Absacal K, Hooper CG. Clinical botanical medicine. Larchmont, NY: Mary Ann Liebert, 2002;223–242.