Chapter 11 Cosmeceutical Botanicals: Part 1

BOTANICAL ADDITIVE MANUFACTURE

The popularity of botanicals is largely due to the aura of natural products. Products derived from plants are felt to be free of synthetic chemicals, somehow providing benefits above and beyond active agents that are created in a laboratory. It may come as a surprise to many that botanicals must undergo a significant amount of chemical processing prior to incorporation into a cosmeceutical and this processing greatly affects the biologic effect of the botanical on the skin surface. Box 11.1 summarizes some of these considerations, which are discussed next.

BOTANICAL ADDITIVES

Botanical pharmacopeias contain thousands of plants with anecdotal purported skin benefits lacking scientific validation. It is not possible to cover all currently existing extracts in this text, yet there are some botanicals that are currently widely used in the cosmeceutical marketplace. These botanicals can be characterized as antioxidants, anti-inflammatories, and skin-soothing agents (Table 11.1).

| Category | Botanical additive |

| Antioxidant | Soy, curcumin, silymarin, pycnogenol |

| Anti-inflammatory | Gingko biloba, green tea |

| Soothing agent | Prickly pear, aloe vera, allantoin, witch hazel, papaya |

BOTANICAL ANTIOXIDANTS

There are many botanical antioxidants, since all plants must protect themselves from oxidation following UV exposure in the outdoor environment in which they grow. These protective mechanisms have evolved over many years, providing interesting chemicals for extraction and incorporation into cosmeceuticals. Antioxidant botanicals quench singlet oxygen and reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, fatty peroxy radicals, and hydroperoxides. Most botanical antioxidants can be classified as flavonoids, carotenoids, and polyphenols. Flavonoids and polyphenols possess a polyphenolic structure accounting for their antioxidant effect while carotenoids are derivatives of vitamin A. The largest source of botanical antioxidants is foods, such as those listed in Table 11.2. These extracts can be used topically, as well as consumed. Other popular botanical antioxidants include soy, curcumin, silymarin, and pycnogenol (Table 11.3).

Table 11.2 Nutritionally derived botanical cosmeceutical antioxidants

| Common botanical name | Chemical class |

| Rutin (apples, blueberries) | Flavone |

| Quercetin (apples, blueberries) | Flavone |

| Hesperedin (lemons, oranges) | Flavone |

| Diosmin (lemons, oranges) | Flavone |

| Mangiferin (mango plant) | Xanthone |

| Mangostin (bilberry plant) | Xanthone |

| Astaxanthin (tomatoes) | Carotenoid |

| Lutein (tomatoes) | Carotenoid |

| Lycopene (tomatoes) | Carotenoid |

| Rosmarinic acid (rosemary) | Polyphenol |

| Hypericin (St John’s wort) | Polyphenol |

| Ellagic acid (pomegranate fruit) | Polyphenol |

| Chlorogenic acid (blueberry leaf) | Polyphenol |

| Oleuropein (olive leaf) | Polyphenol |

Table 11.3 Botanical cosmeceutical antioxidant agents

| Antioxidant | Chemical classification of antioxidant fraction | Cosmeceutical active |

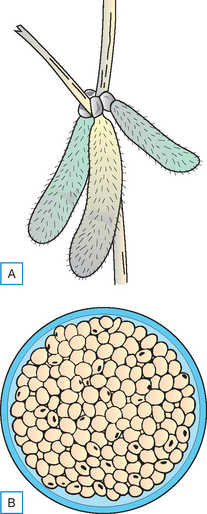

| Soy | Flavonoids | Genistein, daidzein |

| Curcumin | Polyphenol | Tetrahydrocurcumin |

| Silymarin | Flavonoids | Silybin, silydianin, silychristine |

| Pycnogenol | Phenols, phenolic acids |

• Pycnogenol

Pycnogenol is a botanical cosmeceutical antioxidant derived from an extract of French marine pine bark. It is botanically known as Pinus pinaster and is a water-soluble liquid that contains several phenolic constituents, including taxifolin, catechin, and procyanidins. It also contains several phenolic acids, including p-hydroxybenzoic, protocatechuic, gallic, vanillic, p-couric, caffeic, and ferulic acids. It is a potent free radical scavenger that can reduce the vitamin C radical, returning the vitamin C to its active form. The active vitamin C in turn regenerates vitamin E to its active form, maintaining the natural oxygen scavenging mechanisms of the skin intact.

BOTANICAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORIES

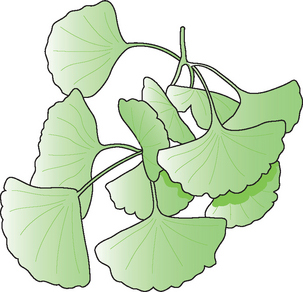

Botanical anti-inflammatory additives are used in many different cosmeceuticals, since aging is in part the end result of chronic inflammation. Commonly used botanical anti-inflammatories include Ginkgo biloba and green tea (Table 11.4).

| Anti-inflammatory | Chemical classification of antiinflammatory | Cosmeceutical active |

| Gingko biloba |

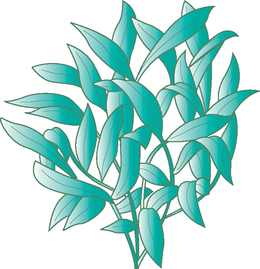

• Green tea (Fig. 11.4)

Green tea is a botanical popular in the Orient for both topical application and oral ingestion. Orally, green tea is said to contain beneficial flavonoids that act as potent endogenous antioxidants. A study by Katiyar et al demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect of topical green tea application with C3H mice. A topically applied green tea extract containing the polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate was found to reduce UVB-induced inflammation. This has been validated by measuring skinfold thickness before and after UVB exposure, which correlates with tissue edema, a sign of inflammation. Even though this is the cosmeceutical industry standard for assessing inflammation, it is a difficult test to replicate and may not directly correlate with a human response. At present, green tea remains a nutritional supplement and not an approved sun protective agent.

BOTANICAL SKIN-SOOTHING AGENTS

Botanical cosmeceuticals can also be used for the purpose of skin soothing. While this is a somewhat nebulous term, skin-soothing agents claim to calm, normalize, replenish, or relax the skin. Botanicals with these properties include prickly pear, aloe vera, allantoin, witch hazel, and papaya (Table 11.5). These plants have been selected for discussion due to their current novelty and popularity.

| Skin-soothing agent | Chemical classification of skin- soothing agent | Cosmeceutical active |

| Prickly pear | Mucilage containing 83% water and 10% sucrose | Tartaric acid, citric acid, and mucopolysaccharides |

| Aloe vera | Mucilage containing 99.5% water and a mixture of mucopolysaccharides, amino acids, hydroxy quinone glycosides, and minerals | Aloin, aloe emodin, aletinic acid, choline, and choline salicylate |

| Allantoin | Comfrey root | Alkaline oxidation of uric acid in a cold environment |

| Witch hazel | Leaf, stem distillate | Tannins |

| Papaya | Proteolytic enzyme | Papain |

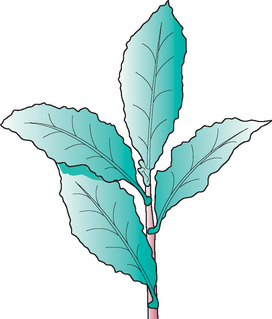

• Aloe vera (Fig. 11.6)

In most skin preparations, aloe vera is added as a powder, not as a mucilage. The composition of aloe vera powder may not be the same as aloe vera juice that oozes from the freshly broken plant leaf. Aloe vera extract is found in soaps, hair shampoos, hand lotions, body moisturizers, etc. It is estimated that aloe vera must be present at a concentration of 10% to have a moisturizing effect in products designed to remain on the skin for extended periods of time.

SUMMARY

Botanical cosmeceuticals provide endless opportunities to add new marketing interest to traditional cleansers and moisturizers. Some botanicals actually contain substances that may provide skin benefits, while others are of questionable value. It is the knowledge base of the dermatologist that will ultimately determine those which are of patient value.

Chatterjee L, Agarwal R, Mukhtar H. Ultraviolet B radiation-induced DNA lesions in mouse epidermis: an assessment using a novel 32P-postlabeling technique. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;229:590–595.

Cossins E, Lee R, Packer L. ESR studies of vitamin C regeneration, order of reactivity of natural source phytochemical preparations. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology International. 1998;45:583–598.

Devaraj S, Vega-Lopez S, Kaul N, Schonlau F, Rohdewald P, Jialal I. Supplementation with a pine bark extract rich in polyphenols increases plasma antioxidant capacity and alters the plasma lipoprotein profile. Lipids. 2002;37:931–934.

Glazier MG, Bowman MA. A review of the evidence for the use of phytoestrogens as a replacement for traditional estrogen replacement therapy. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161:1161–1172.

Hsu S. Green tea and the skin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2005;52:1049–1059.

Joyeux M, Lobstein A, Anton R, Mortier F. Comparative antilipoperoxidant, antinecrotic and scavenging properties of terpenes and biflavones from Ginkgo and some flavonoids. Plant Medicine. 1995;61:126–129.

Katiyar SK, Elmets CA, Agarwal R, et al. Protection against ultraviolet-B radiation-induced local and systemic suppression of contact hypersensitivity and edema responses in C3H/HeN mice by green tea polyphenols. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 1995;62:855–861.

Katiyar SK, Korman NJ, Mukhtar H, Agarwal R. Protective effects of silymarin against photocarcinogenesis in a mouse skin model. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89:556–566.

Kim SJ, Lim MH, Chun IK, Won YH. Effects of flavonoids of Ginkgo biloba on proliferation of human skin fibroblast. Skin Pharmacology. 1997;10:200–205.

McKeown E. Aloe vera. Cosmetics and Toiletries. 1987;102:64–65.

Maheux R, Naud F, Rioux M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effect of conjugated estrogens on skin thickness. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;170:642–649.

Miyazaki K, Hanamizu T, Soe T, Chiba K, Kinoshita T, Yoshikawa S. Topical application of Bifidobacterium-fermented soy milk extract containing genistein and daidzein improves rheological and physiological properties of skin. Journal of Cosmetic Science. 2004;55:473–479.

Nishioka K, Hidaka T, Nakamura S, et al. Pyconogenol, French maritime pine bark extract, augments endothelium-dependent vasodilation in humans. Hypertension Research. 2007;30:775–780.

Schonlau F. The cosmetic Pycnogenol. Journal of Applied Cosmetology. 2002;20:241–246.

Sudel KM, Venzke K, Mielke H, et al. Novel aspects of intrinsic and extrinsic aging of human skin: beneficial effects of soy extract. Photochemistry and Photobiology. 2005;81:581–587.

Waller T. Aloe vera. Cosmetics and Toiletries. 1992;107:53–54.

Wiseman H, O’Reilly JD, Adlercreutz H, et al. Isoflavone phytoestrogens consumed in soy decrease F-2-isoprostane concentrations and increase resistance of low-density lipoprotein to oxidation in humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;72:395–400.