20 Coronary heart disease

CHD kills over 6.5 million people worldwide each year.

Epidemiology

The UK has seen a steady decline in deaths from CHD of about 4.5% per annum since the late 1970s. A recent study indicated that both reductions in major risk factors and improvements in treatment have contributed to this reduction (Unal et al., 2004). While impressive, this rate of decline has not been as great as in other countries like Australia and Finland. In Eastern European countries, the death rates from CHD have increased significantly during the same period.

Risk factors

Traditionally, the main potentially modifiable risk factors for CHD have been considered to be hypertension, cigarette smoking, raised serum cholesterol and diabetes. More recently psychological stress and abdominal obesity have gained increased prominence (Box 20.1). Patients with a combination of all these risk factors are at risk of suffering a myocardial infarction some 500 times greater than individuals without any of the risk factors. Stopping smoking, moderating alcohol intake, regular exercise and consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables were associated independently and additively with reduction in the risk of having a myocardial infarction.

Aetiology

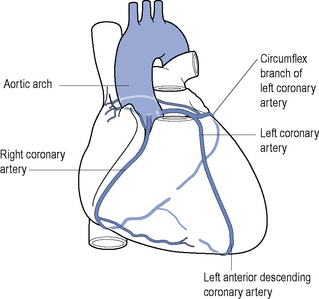

The vast majority of CHD occurs in patients with atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries (see Fig. 20.1) that starts before adulthood. The cause of spontaneous artherosclerosis is unclear, although it is thought that in the presence of hypercholesterolaemia, a non-denuding form of injury occurs to the endothelial lining of coronary arteries and other vessels. This injury is followed by subendothelial migration of monocytes and the accumulation of fatty streaks containing lipid-rich macrophages and T-cells. Almost all adults, and 50% of children aged 11–14 years, have fatty streaks in their coronary arteries. Thereafter, there is migration and proliferation of smooth muscle cells into the intima with further lipid deposition. The smooth muscle cells, together with fibroblasts, synthesise and secrete collagen, proteoglycans, elastin and glycoproteins that make up a fibrous cap surrounding cells and necrotic tissue, together called a plaque. The presence of atherosclerotic plaques results in narrowing of vessels and a reduction in blood flow and a decrease in the ability of the coronary vasculature to dilate and this may become manifest as angina. Associated with the plaque rupture is a loss of endothelium. This can serve as a stimulus for the formation of a thrombus and result in more acute manifestations of CHD, including unstable angina (UA) and myocardial infarction. Plaque rupture caused by physical stresses or plaque erosion may precipitate an acute reaction. Other pathological processes are probably involved, including endothelial dysfunction which alters the fibrin–fibrinolysis balance and the vasoconstriction–vasodilation balance. There is interest in the role of statins and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in modifying endothelial function.

Measurement of acute phase inflammatory reactions, such as fibrinogen and CRP, has a predictive association with coronary events. High-sensitivity CRP assays have been used in populations without acute illness to stratify individuals into high-, medium- and low-risk groups. In patients with other risk factors, however, CRP adds little prognostic information. CRP is produced by atheroma, in addition to the major producer which is the liver, and is an inflammatory agent as well as a marker of inflammation. Evidence is emerging that drug therapy which reduces CRP in otherwise healthy individuals reduces the incidence of major cardiac events (Ridker, 2008).

Modification of risk factors

Common to all stages of CHD treatment is the need to reduce risk factors (Table 20.1). The patient needs to appreciate the value of the proposed strategy and to be committed to a plan for changing their lifestyle and habits, which may not be easy to achieve after years of smoking or eating a particular diet. Preventing CHD is important but neither instant nor spectacular. It may require many sessions of counseling over several years to initiate and maintain healthy habits. It may also involve persuasion of patients to continue taking medication for asymptomatic disorders such as hypertension or hyperlipidaemia. The general public, with government as its agent, need to agree that a reduction in the incidence of CHD is worth some general changes in lifestyle or liberty, for example, such as prohibiting the freedom to smoke in public. National campaigns to encourage healthy eating or exercise are expensive, as is the long-term medical treatment of hypertension or hyperlipidaemia, and such strategies must have the backing of governments to succeed. It has been argued that community-wide campaigns on cholesterol reduction have had measurable benefits in Finland, the USA and elsewhere, at least in high-risk, well-educated and affluent groups. It follows that the next challenge is to extend that success to poorer, ethnically diverse groups and to those portions of the population with mild-to-moderate risk.

Table 20.1 Effect of interventions on risk of myocardial infarction

| Intervention | Control | Benefit of intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Stopping smoking for ≥5 years | Current smokers | 50–70% lower risk |

| Reducing serum cholesterol | 2% lower risk for each 1% reduction in cholesterol | |

| Treatment of hypertension | 2–3% lower risk for each 1 mmHg decrease in diastolic pressure | |

| Active lifestyle | Sedentary lifestyle | 45% lower risk |

| Mild to moderate alcohol consumption (approx. 1 unit/day) | Total abstainers | 25–45% lower risk |

| Low-dose aspirin | Non-users | 33% lower risk in men |

| Postmenopausal oestrogen replacement | Non-users | 44% lower risk |

The quality of data associated with these interventions varies greatly and figures may not apply to all patient groups.

Clinical syndromes

Stable angina

Treatment of stable angina is based on two principles:

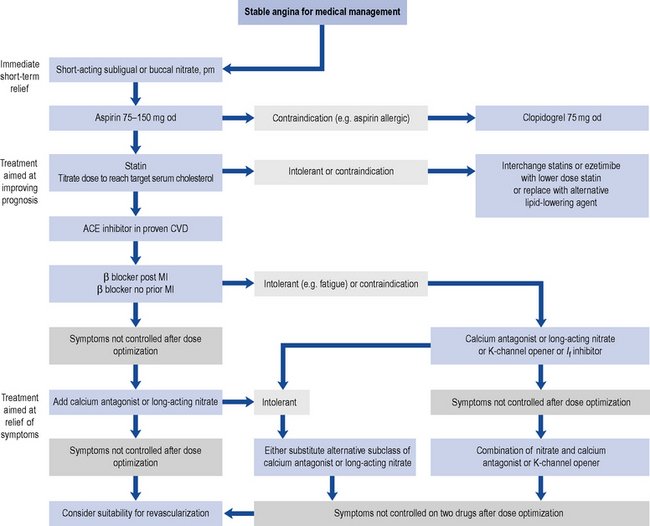

Pharmacological therapy can be considered a viable alternative to invasive strategies, providing similar results without the complications associated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). An algorithm for addressing both these principles is outlined in Fig. 20.2. In addition, diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia in patients with stable angina should be well controlled. Smoking cessation, without or with pharmacological support, and weight loss should be attempted.

Antithrombotic drugs

Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel inhibits ADP activation of platelets and is useful as an alternative to aspirin in patients who are allergic or cannot tolerate aspirin. Data from one major trial (CAPRIE Steering Committee, 1996) indicate that clopidogrel is at least as effective as aspirin in patients with stable coronary disease. The usual dose is 300 mg once, then 75 mg daily. Although less likely to cause gastric erosion and ulceration, gastro-intestinal bleeding is still a major complication of clopidogrel therapy. There is evidence that the combination of a proton pump inhibitor and aspirin is as effective as using clopidogrel alone in patients with a history of upper gastro-intestinal bleeding.

COX-2 inhibitors

The analgesic and anti-inflammatory action of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is believed to depend mainly on their inhibition of COX-2, and the unwanted gastro-intestinal effects of NSAIDs on their inhibition of COX-1. COX-2 inhibition reduces the production of prostacyclin, which has vasodilatory and platelet-inhibiting effects. Studies have raised concern about the cardiovascular safety of NSAIDs. Initially, the concern was focussed on the selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and a link to an increased cardiovascular risk. Recently, evidence has shown the more traditional non-selective NSAIDs increase cardiovascular risk in both patients with established CVD and in the healthy population (Fosbol et al., 2010). NSAIDs with high COX-2 specificity increase the risk of myocardial infarction and should be avoided where possible in patients with stable angina.

ACE inhibitors

The use of ACE inhibitors in patients without myocardial infarction or left ventricular damage is based on two trials: the HOPE study (Yusuf et al., 2000) which studied ramipril and the EUROPA (2003) study which used perindopril. These trials also identified an incidental delay in the onset of diabetes mellitus in susceptible individuals which may be of long-term benefit to them. The HOPE study, a secondary prevention trial, investigated the effect of an ACE inhibitor on patients over 55 years old who had known atherosclerotic disease or diabetes plus one other cardiovascular risk factor. The use of ramipril decreased the combined endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction or cardiovascular death by approximately 22%. The benefits were independent of blood pressure reduction. This has major implications for the management of CHD patients, both for the decision to treat all and the choice of treatment. At present the use of ACE inhibitors in patients with coronary disease, but without myocardial infarction, has general acceptance and is recommended in European guidelines.

Statins

Earlier studies focused on patients with ‘elevated’ cholesterol, but all patients with coronary risk factors benefit from reduction of their serum cholesterol level. It is now clear that there is no ‘safe’ level of cholesterol for patients with CAD and that there is a continuum of risk down to very low cholesterol levels. Levels of LDL-C of <2 mmol/L and total cholesterol <4 mmol/L are recommended for patients with established CVD (NICE, 2008). Statins should be prescribed alongside lifestyle advice for both primary prevention of CVD and in those with established CVD (see Chapter 24 for more detail).

Symptom relief and prevention

β-Blockers

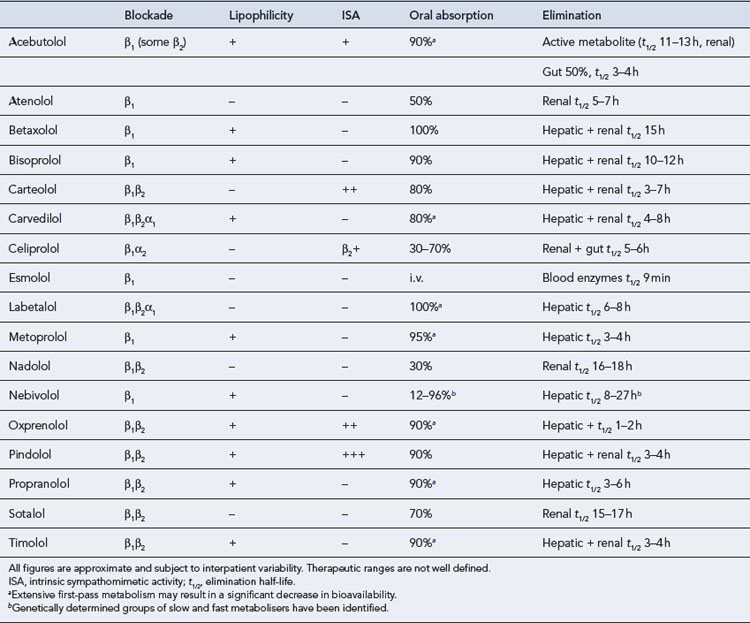

All β-blockers tend to reduce renal blood flow, but this is only important in renal impairment. Drugs eliminated by the kidney (Table 20.2) may need to be given at lower doses in the renally impaired or in the elderly, who are particularly susceptible to the CNS-mediated lassitude. Drugs eliminated by the liver have a number of theoretical interactions with other agents that affect liver blood flow or metabolic rate, but these are rarely of clinical significance since the dose should be titrated to the effect. Likewise, although there is theoretical support for the use of agents with high intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (ISA) to reduce the incidence or severity of drug-induced heart failure, there is no β-blocker that is free from this problem, and clinical trials of drugs with ISA have generally failed to show any extra benefit.

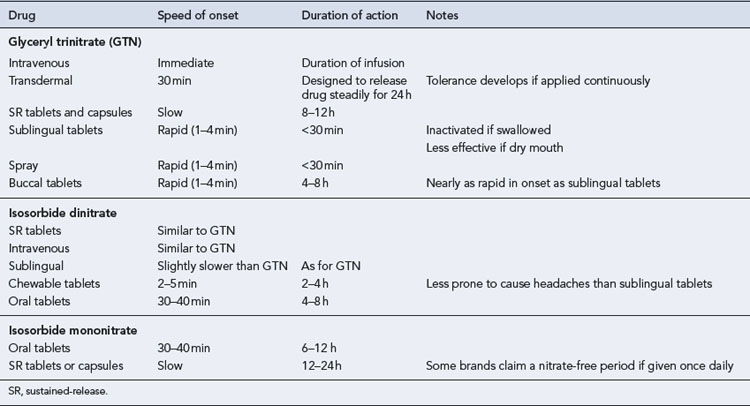

Nitrates

Three main nitrates are used: GTN (mainly for sublingual, buccal, transdermal and intravenous routes), isosorbide dinitrate and isosorbide mononitrate. All are effective if given in appropriate doses at suitable dose intervals (Table 20.3). Since isosorbide dinitrate is metabolised to the mononitrate, there is a preference for using the more predictable mononitrate, but this is not a significant clinical factor. A more relevant feature may be that whereas the dinitrate is usually given three or four times a day, the mononitrate is given once or twice a day. Slow-release preparations exist for both drugs.

Nicorandil

Nicorandil is a compound that exhibits the properties of a nitrate but which also activates ATP-dependent potassium channels. The IONA Study Group (2002) compared nicorandil with placebo as ‘add-on’ treatment in 5126 high-risk patients with stable angina. The main benefit for patients in the nicorandil group was a reduction in unplanned admission to hospital with chest pain. The study did not tell us when to add nicorandil to combinations of antianginals such as β-blockers, CCBs and long-acting nitrates. There is a theoretical benefit from these agents in their action to promote ischaemic preconditioning. This phenomenon is seen when myocardial tissue is exposed to a period of ischaemia prior to sustained coronary artery occlusion. Prior exposure to ischaemia renders the myocardial tissue more resistant to permanent damage. This mechanism is mimicked by the action of nicorandil.

Acute coronary syndrome

Definition and cause

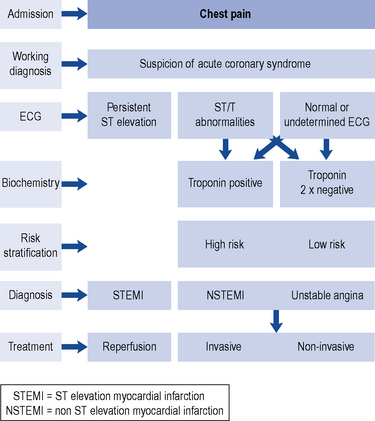

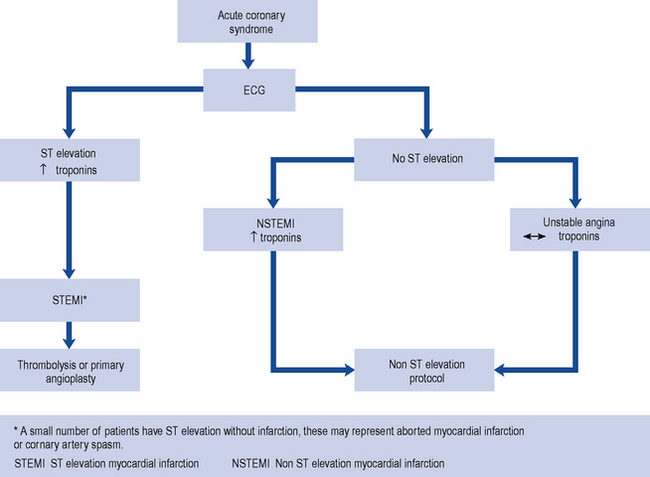

The group of conditions referred to as ACS often present with similar symptoms of chest pain which is not, or only partially, relieved by GTN. These conditions include acute myocardial infarction (AMI), UA and non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). AMI with persistent ST segment elevation on the ECG usually develops Q waves, indicating transmural infarction. UA and NSTEMI present without persistent ST segment elevation and are managed differently, although a similar early diagnostic and therapeutic approach is employed. All patients with ACS should be admitted to hospital for evaluation, risk stratification and treatment. The spectrum of ACS is described in Fig. 20.3.

The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE; available at http://www.outcomes-umassmed.org/GRACE/) is an international registry which has enrolled patients with ACS (UA, NSTEMI and STEMI) since 1999. The registry indicates a similar incidence of UA, NSTEMI and STEMI.

The classification of ACS based on ECG findings and measurement of troponin is shown in Fig. 20.4.

Treatment of ST elevation myocardial infarction

Treatment of STEMI may be divided into three categories:

The management of heart failure and arrhythmias are covered more extensively in Chapters 21 and 22, respectively, and will not be discussed here. The remaining therapeutic aims are to relieve pain, return patency to the coronary arteries, minimise infarct size, provide prophylaxis to arrhythmias and institute secondary prevention.

Immediate care to alleviate pain, prevent deterioration and improve cardiac function

Antiplatelet therapy. An aspirin tablet chewed as soon as possible after the infarct and followed by a daily dose for at least 1 month has been shown to reduce mortality and morbidity. Follow-up studies have demonstrated additional benefit in continuing to take daily aspirin, probably for life. The reduction in mortality is additional to that obtained from thrombolytic therapy (Table 20.4). Clopidogrel, given in addition to aspirin, can further improve coronary artery blood flow but the additional absolute reduction in mortality is small, at approximately 0.4% (Sabatine et al., 2005). In suspected heart attack patients in the UK, both aspirin and clopidogrel may be administered by the ambulance crew.

Table 20.4 Vascular deaths at 35 days in the ISIS-2 study (1990)

| Placebo | 13.2% |

| Aspirin | 10.7% |

| Streptokinase | 10.4% |

| Aspirin + streptokinase | 8.0% |

Restoring coronary flow and myocardial tissue perfusion

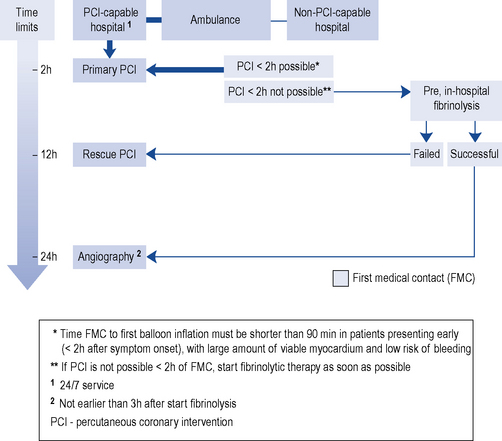

Treatment within 1 h has been found to be particularly advantageous, although difficult to achieve, for logistical reasons, in anyone who has an infarct outside hospital. Prioritisation of ambulances to emergency calls for chest pain and appropriately equipped paramedics or primary care doctors administering fibrinolytics out of hospital have all helped reduce delay in fibrinolysis administration. Increased numbers of and direct access to hospitals offering primary angioplasty sites has further reduced the time to myocardial tissue reperfusion. Current reperfusion strategies are outlined in Fig. 20.5.

Fig. 20.5 Reperfusion strategies. The thick arrow (dark blue) indicate the preferred strategy (Van de Werf, 2008).

Fibrinolytics

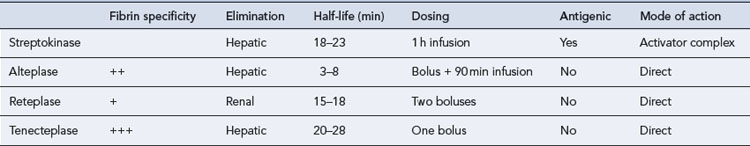

Fibrinolytic agents (Table 20.5) have transformed the management of these patients by substantially improving coronary artery patency rates which has translated into a 25% relative reduction in mortality. The risk of haemorrhagic stroke (around 1%) and a failure to adequately reperfuse the affected myocardium in approximately 50% of cases have remained despite advances in fibrinolytics.

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy

Patients undergoing primary PCI should receive aspirin and clopidogrel as early as possible. Antiplatelet naïve patients should receive 300 mg of aspirin and 600 mg of clopidogrel. In the UK and elsewhere in Europe, these are administered by paramedics. Prasugrel has less metabolic activation steps and has a faster and more reliable onset of antiplatelet action. In combination with aspirin, it is recommended (NICE, 2009) for preventing atherothrombotic events in individuals undergoing PCI only when:

Fibrinolytics

A low dose of fondaparinux, a synthetic, indirect anti-Xa agent, has been found to be superior to placebo or heparin in preventing death and reinfarction in patients who received fibrinolytic therapy (OASIS-6 Trial Group, 2006).

Bivalirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor, reduces reinfarction rates compared to heparin when given with streptokinase but has not been studied with fibrin-specific agents. This combination resulted in a non-significant increase in non-cerebral bleeding complications (HERO-2 Trial Investigators, 2001).

Trials using various dosing combinations of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors with newer fibrinolytic agents have not found a regimen that increases overall survival (Menon et al., 2004).

All the major trials have used specific ECG criteria for entry, usually ST elevation in adjacent leads or LBBB, and eliminated patients with major contraindications to fibrinolysis (Box 20.2). Confusion often arises about the term ‘relative contraindication’. For example, systolic hypertension is common in AMI, so most protocols recommend lowering the blood pressure with either a β-blocker or intravenous nitrates before commencing fibrinolysis. An increasing number of patients are on warfarin and this again is regarded as a relative contraindication to fibrinolysis; thresholds for the use of fibrinolysis in patients on warfarin vary from an INR of 2–2.4. The use of fibrinolytic therapy in patients with relative contraindications should take into account the site of the myocardial infarction and the likely size of the infarction. For example, in patients with a large anterior myocardial infarction the benefits of fibrinolysis may outweigh risk. In patients where there is a serious concern regarding bleeding following fibrinolysis, primary angioplasty should be considered.

Management of complications

Arrhythmias

Life-threatening arrhythmias such as ventricular tachycardia, sustained VF or atrio-ventricular block occur in about one fifth of patients presenting with a STEMI, although this is decreasing due to early reperfusion therapy. β-Blockers have been the subject of many studies because of their anti-arrhythmic potential and because they permit increased subendocardial perfusion. In studies undertaken prior to the widespread use of fibrinolytics, the early administration of an intravenous β-blocker was shown to limit infarct size and reduce mortality from early cardiac events. A post hoc analysis of the use of atenolol in the GUSTO-I trial and a systematic review (Freemantle et al., 1999) did not support the routine, early intravenous use of β-blockers and, therefore, oral β-blockers are started within 24 h of the event. If a β-blocker is contraindicated because of respiratory or vascular disorders, verapamil may be used, since it has been shown to reduce late mortality and reinfarction in patients without heart failure, although it shows no benefit when given immediately after an infarct. Diltiazem is less effective but may be used as an alternative. This is clearly not a class effect; other echannel blockers have produced different results and nifedipine increases mortality in patients following a myocardial infarction.

Blood glucose

Patients with a myocardial infarction are often found to have high serum and urinary glucose levels, usually described as a stress response. The CREATE-ECLA trial (Mehta et al., 2005) studied more than 20,000 patients and showed a neutral effect of insulin on mortality, cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock. Current guidelines do not support the routine use of insulin in STEMI in patients not previously known to be diabetic.

Up to 20% of patients who have a myocardial infarction have diabetes. Moreover, diabetic patients are known to do poorly after infarction, with almost double the mortality rate of non-diabetics. In these patients, an intensive insulin regimen, both during admission and for 3 months after, was found to save lives (Malmberg, 1997). However, the follow-up study (Malmberg et al., 2005) did not show any mortality benefit from intensive insulin therapy compared to standard therapy. In patients with diabetes, it appears reasonable, however, to continue to control blood glucose levels within the normal range immediately post-infarct.

Prevention of further infarction or death (secondary prophylaxis)

Lipid-lowering agents

Reduction of cholesterol through diet and use of lipid-lowering agents are effective at reducing subsequent mortality and morbidity in patients with established CAD. Patients with established CHD should be treated to ensure LDL-C is less than 2 mmol/L and total cholesterol less than 4 mmol/L (see Chapter 24). In patients with AMI or high-risk NSTEMI, there was a reduction in the combination end point of death, myocardial infarction, or documented UA requiring hospitalisation, revascularisation or stroke when patients were treated with high intensity statin (atorvastatin 80 mg) compared to standard statin therapy (Cannon et al., 2004). A meta-analysis of studies (Josan et al., 2008) reaffirmed the benefit of high intensity statin therapy especially in those patients with ACSs. An additional finding of particular interest was that the results were significant for the high intensity treatment arms despite approximately half of patients not achieving LDL-C of less than 2 mmol/L.

β-Blockers

Long-term use of a β-blocker has been shown in several studies to decrease mortality in patients in whom there is no contraindication. β-Blockade should be avoided in individuals with heart block, bradycardia, asthma, obstructive airways disease or peripheral vascular disease. One large cohort study compared low and high doses of β-blockers with no therapy and found benefit in all treated patients with similar survival rates but a lower heart failure rate in the low-dose group (Rochon et al., 2000).

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

ACE inhibitors have been tried in various doses and durations and have proved beneficial in reducing the incidence of heart failure and mortality. In all but the earliest trials, patients were given an ACE inhibitor for 4–6 weeks and treatment continued in patients with signs or symptoms of heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction. The HOPE study (Yusuf et al., 2000) found that ramipril improved survival in all groups of patients with CHD and this has led clinicians to continue ACE inhibitors in all patients with a myocardial infarction over the age of 55 and in younger patients with evidence of left ventricular dysfunction. Contraindications to their use include hypotension and intractable cough.

There is considerable interest in focusing on the possible benefits of combining ACE inhibition with angiotensin II receptor blockers. Angiotensin blockade alone does not cause the accumulation of bradykinins that may be part of the benefit of using ACE inhibitors. Clinical trials (OPTIMAAL Study Group, 2002; VALIANT Investigators, 2003) have failed to find a benefit over ACE inhibition. Nonetheless, angiotensin receptor blockers are probably suitable in patients who cannot tolerate an ACE inhibitor. The relative benefits of ACE inhibitors and other treatments are shown in Table 20.6.

Table 20.6 Relative benefits of treating 1000 patients for myocardial infarction (MI)

| Intervention | Events prevented |

|---|---|

| Intravenous β-adrenoceptor blocker | 6 deaths |

| ACE inhibitor | 6 deaths |

| Aspirin | 20–25 deaths |

| Streptokinase (in hospital) | 20–25 deaths |

| Alteplase (in hospital) | 35 deaths |

| Streptokinase (before hospital) | 35–40 deaths |

| Fibrinolysis 4½–1 h earlier | 15 deaths |

| Long-term aspirin | 16 deaths/MI/strokes |

| Long-term β-blockade | 18 deaths/MI |

| Long-term ACE inhibitor | 21–45 deaths/MI |

| 10% reduction in serum cholesterol | 7 deaths/MI |

| Stopping smoking | 27 deaths |

Adapted from McMurray and Rankin (1994).

Eplerenone

In patients with heart failure, post-AMI, an improvement in survival and decreased cardiovascular mortality and hospitalisation was seen in those taking the aldosterone antagonist eplerenone (EPHESUS Trial; Pitt et al., 2003). Serious hyperkalemia occurred more frequently in the eplerenone arm and monitoring of serum potassium is warranted when used in practice.

Antidepressants

Anxiety is almost inevitable and a quarter of patients who have suffered a myocardial infarction subsequently experience marked depression. Post-myocardial infarction depression is associated with poor medication compliance, a lower quality-of-life score and a four-fold increase in mortality (Januzzi et al., 2000). Antidepressant treatments have not been subjected to formal trials but it seems reasonable to try to reduce the depression. There is concern about the potential for older antidepressants, such as tricyclic antidepressants, to increase the QT interval and cause arrhythmias. Newer antidepressants are less prone to cause these arrhythmias and selective seretonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs) are preferred.

Nitrates

Studies on nitrates in myocardial infarction were mostly completed before fibrinolysis was widely used. Nitrates improve collateral blood flow and aid reperfusion, thus limiting infarct size and preserving functional tissue. ISIS-4 (1993) and GISSI-3 (1994) demonstrated that nitrates did not confer a survival advantage in patients receiving fibrinolysis. Sublingual nitrates may be given for immediate pain relief, and the use of intravenous or buccal nitrates can be considered in patients whose infarction pain does not resolve rapidly or who develop ventricular failure.

Anticoagulants and antiplatelets

Anticoagulation with warfarin is not generally recommended following a myocardial infarction, despite promising results in trials that have practiced exceptionally good anticoagulant monitoring. This is partly because of the success of antiplatelet therapy with aspirin. Aspirin does not have the same need for expensive and time-consuming follow-up and monitoring as warfarin, and is associated with fewer drug interactions. Clopidogrel has been shown to be beneficial, in addition to aspirin, in patients who have had a myocardial infarction (COMMIT, 2005). As the number of patients who receive a stent increases, the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel for a year or longer is now more frequent. Routine use of dipyridamole and sulfinpyrazone is not recommended after a myocardial infarction.

Treatment of non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes

Patients with NSTEMI may either be treated with an interventional strategy, where all patients undergo angiography and PCI following admission, or conservatively where they undergo angiography and intervention only if they remain unstable or have a positive exercise test. Initial trials of early intervention did not demonstrate any benefit but with the advent of advanced angioplasty techniques using stents and adjuvant drug therapies including clopidogrel and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists, there appears to be a clear advantage for an interventional strategy in high-risk patients (Fox et al., 2005).

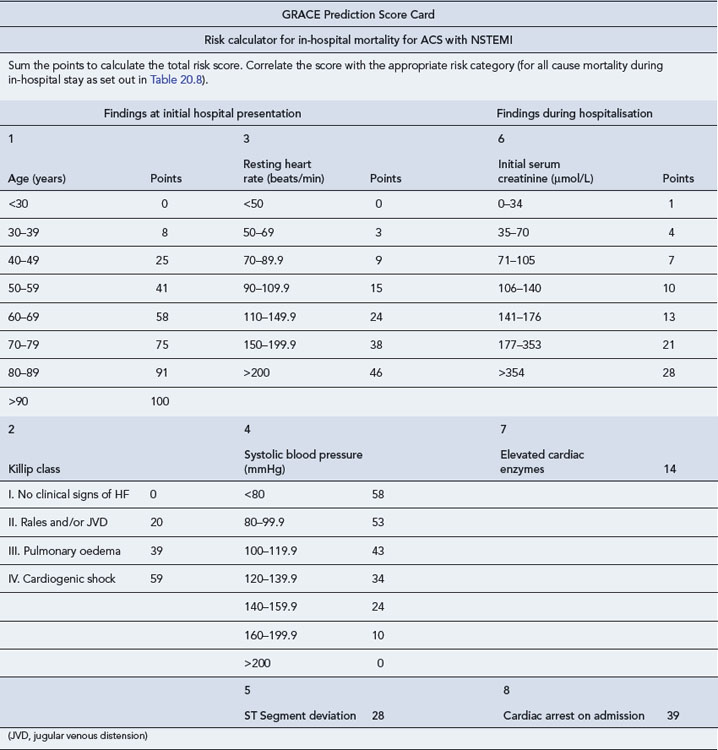

Measures of risk can be derived from the clinical assessment of a patient and the use of a formal risk scoring system, such as the GRACE, PURSUIT, PREDICT or TIMI scores. Scores based on clinical trial data generally exclude patients who are at high risk of an adverse cardiovascular outcome such as the elderly, or those with renal or heart failure, and as a consequence the evidence for clinical and cost-effectiveness of therapeutic interventions is confined to patients at lower to intermediate levels of risk. Risk score based on registry data, for example, GRACE, may provide a more realistic estimation of risk (Tables 20.7 and 20.8).

Table 20.7 Classification of high-risk patients with NSTEMI as determined by the GRACE prediction score card and nomogram

Table 20.8 GRACE prediction nomogram for all cause mortality during in-hospital stay and up to 6 months post discharge

| Risk category (tertiles) | GRACE risk score | In-hospital death (%) |

| Low | <109 | <1 |

| Intermediate | 109–140 | 1–3 |

| High | >140 | >3 |

| Risk category (tertiles) | GRACE risk score | Post-discharge to 6 months |

| Low | <89 | <3 |

| Intermediate | 89–118 | 3–8 |

| High | >118 | >8 |

GRACE Registry. Available at www.outcomes-umassmed.org/GRACE/ index.cfm.

Antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs

The CURE study (2001) showed that clopidogrel, given as a loading dose of 300 mg followed by 75 mg daily in combination with aspirin and heparin, reduced the combined end point of death, myocardial infarction and revascularisation in all patients with NSTEMI. Clopidogrel needs to be continued for 12 months but should be stopped 5–7 days before any major surgery to reduce the risk of bleeding.

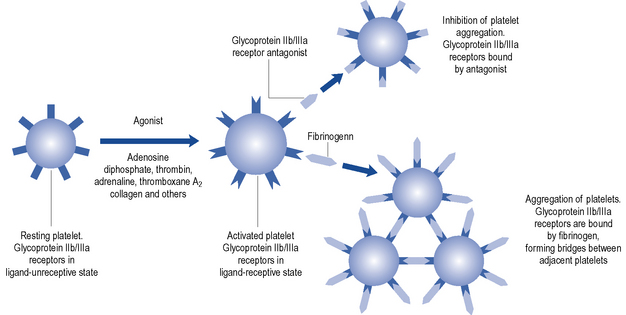

Expression of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa is one of the final steps in the platelet aggregation cascade. Inhibiting these receptors has been a strategy prior to, and during, PCI for some time. Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors bind to the IIb/IIIa receptors on platelets (Fig. 20.6) and prevent cross-linking of platelets by fibrinogen. There are three classes of these agents: murine-human chimeric antibodies, for example, abciximab; synthetic peptides, for example, eptifibatide; and non-peptide synthetics, for example, tirofiban. Oral agents are ineffective and the murine-human chimeric antibodies appear to be effective only in the context of PCI.

In high-risk patients undergoing PCI and receiving background heparin, triple antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors) has been shown to be superior to standard dose dual-antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) particularly in troponin positive individuals (Kastrati et al., 2006). However, much of this evidence was generated before the introduction of higher doses of clopidogrel or more potent oral antiplatelet agents.

There is no clear benefit to giving glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors more than 4 h before PCI (upstream) compared to waiting until immediately before or during the procedure (deferred) (Stone et al., 2007).

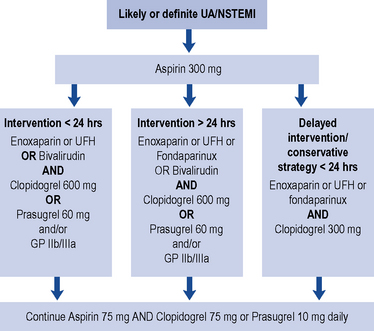

Currently, all patients with a likely or definite diagnosis of NSTEMI should receive a loading dose of aspirin 300 mg (see Fig. 20.7). Patients undergoing PCI intervention should have a higher loading dose of 600 mg of clopidogrel or 60 mg of prasugrel, unless contraindicated, to reduce events during and after PCI. Clopidogrel is often given as 300 mg on admission and a further 300 mg when the decision to intervene is made. Prasugrel, with its faster time to maximum effect, has demonstrated some benefit but routine use is not recommended (NICE, 2009). Patients who are not planned for intervention should receive a lower loading dose of clopidogrel 300 mg.

Patient care

Some of the common therapeutic problems encountered in the management of CHD are described in Table 20.9.

Table 20.9 Common therapeutic problems in coronary heart disease

| Problem | Comment |

|---|---|

| Used incorrectly, nitrates may cause hypotensive episodes or collapse | Advise to sit down when using nitrate sprays or sublingual tablets |

| A daily nitrate-free period is required to maintain efficacy of nitrates | Avoid long-acting preparations and prescribe asymmetrically (e.g. 8 a.m. and 2 p.m.) |

| NSAIDs are associated with renal failure when given with ACE inhibitors | Warn patients to use paracetamol as their analgesic of choice |

| Speed is essential when patients need fibrinolytic drugs after infarction | Arrange emergency admission to hospital where fast-track systems should exist |

| Aspirin may cause gastro-intestinal bleeding | Advise on taking with food and water. Consider use of prophylactic agents in high-risk patients |

| β-Blockers are often considered unpleasant to take | Encourage patient to use regularly. Change the time of day. Consider a vasodilator if cold extremities are a problem. Consider verapamil or diltiazem |

| β-Blockers are contraindicated in respiratory and peripheral vascular disease | Consider verapamil or diltiazem. Pay strict attention to other treatments and removal of precipitating factors |

| Patients often receive multiple drugs for prophylaxis and for treatment of co-existing disorders | Use once-daily preparations, dosing aids and intensive social and educational support. Avoid all unnecessary drugs |

| ACE inhibitors are contraindicated in pregnancy, especially the first trimester | Advise women of child-bearing years to avoid conception or seek specialist advice first |

Answer

He should receive GTN spray or sublingual tablets for the chest symptoms that are almost certainly angina. He should take aspirin daily and a statin if his lipid profile is abnormal. Some prescribers would give a statin in almost all diabetic, CHD patients and likewise an ACE inhibitor. Certainly, any hypertension should be treated aggressively so that the diastolic pressure is less than 80 mmHg. A β-blocker may also be useful to control blood pressure and prevent further episodes of angina, but many prescribers would wait until there was evidence of failure of the other therapies. In view of his relatively young age, a referral to a cardiologist for possible angiography would be considered. Dietary advice and help to stop smoking, if needed, would be given. Diabetic treatments should be given (see Chapter 44).

Answers

Cannon C.P., Braunwald E., McCabe C.H., et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2004;350:1495-1504.

CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet. 1996;348:1329-1339.

COMMIT (Clopidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial) Collaborative Group. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1607-1621.

CURE (Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events) Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2001;345:494-502.

EUROPA Study Investigators. The EURopean trial On reduction of cardiac events with perindopril in stable coronary artery disease investigators. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study). Lancet. 2003;362:782-788.

Fosbøl E.L., Folke F., Jacobsen S., et al. Cause-specific cardiovascular risk associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among healthy individuals. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2010;3:395-405. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.861104

Fox K.A.A., Poole-Wilson P., Clayton T., et al. Five-year outcome of an interventional strategy in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the British Heart Foundation RITA 3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2005;366:914-920.

Fox K., Garcia M.A.A., Ardissino D., et al. The task force on the management of stable angina pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris. Eur. Heart J.. 2006;27:1341-1381. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl001

Freemantle N., Cleland J., Young P., et al. Beta blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. Br. Med. J.. 1999;318:1730-1737.

GISSI-3 (Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’infarto Miocardico). Effects of lisinopril and transdermal glyceryl trinitrate singly and together on 6-week mortality and ventricular function after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1994;343:1115-1122.

HERO (Hirulog and Early Reperfusion or Occlusion)-2 Trial Investigators. Thrombin-specific anticoagulation with bivalirudin versus heparin in patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: the HERO-2 randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:1855-1863.

IONA Study Group. Effect of nicorandil on coronary events in patients with stable angina: the Impact of Nicorandil in Angina (IONA) randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;349:1269-1275.

ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. In-hospital mortality and clinical course of 20, 891 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction randomised between tissue plasminogen activator or streptokinase with or without heparin. Lancet. 1990;336:71-75.

ISIS-4 (Fourth International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. A randomised factorial trial assessing early oral captopril, oral mononitrate, and intravenous magnesium sulphate in 58,050 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1995;345:669-685.

Januzzi J.L., Stern T.A., Pasternak R.C., et al. The influence of anxiety and depression on outcomes of patients with coronary artery disease. Arch. Intern. Med.. 2000;160:1913-1921.

Josan K., Majumdar S.R., McAlister F.A. The efficacy and safety of intensive statin therapy: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Can. Med. Assoc. J.. 2008;178:576-584.

Kastrati A., Mehilli J., Neumann F.J., et al. Abciximab in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel pretreatment: the ISAR-REACT 2 randomized trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2006;295:1531-1538.

Malmberg K., for the DIGAMI (Diabetes Mellitus Insulin Glucose Infusion in Acute Myocardial Infarction) Study Group. Prospective randomised study of intensive insulin treatment on long term survival after acute myocardial infarction in patients with diabetes mellitus. DIGAMI (Diabetes Mellitus, Insulin Glucose Infusion in Aacute Myocardial Infarction) Study Group. Br. Med. J.. 1997;314:1512-1515.

Malmberg K., Ryden L., Wedel H., et al. Intense metabolic control by means of insulin in patients with Diabetes Mellitus and Acute Myocardial Infarction (DIGAMI 2): effects on mortality and morbidity. Eur. Heart J.. 2005;26:650-661.

McMurray J.J.V., Rankin A.C. Treatment of myocardial infarction, unstable angina and angina pectoris. Br. Med. J.. 1994;309:1343-1350.

Mehta S.R., Yusuf S., Diaz R., et al. Effect of glucose-insulin-potassium infusion on mortality in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the CREATE-ECLA randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2005;293:437-446.

Menon V., Harrington R.A., Hochman J.S., et al. Thrombolysis and adjunctive therapy in acute myocardial infarction. Chest. 2004;126:549S-575S.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and the Modification of Blood Lipids for the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. London: NICE; 2008. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/CG067

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Prasugrel for the Treatment of Acute Coronary Syndromes with Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. London: NICE; 2009. Available at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA182

OASIS-6 Trial Group. Effects of fondaparinux on mortality and reinfarction in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2006;295:1519-1530.

OPTIMAAL Study Group. Effect of losartan and captopril on mortality and morbidity in high-risk patients after acute myocardial infarction: the OPTIMAAL randomized trial. Lancet. 2002;360:752-780.

Pitt B., Remme W., Zannad F., for the Eplerenone Post-Acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study Investigators, et al. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2003;348:1309-1321.

Ridker P.M., Danielson E., Fonseca F.A.H., for the JUPITER Study Group, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2008;359:2195-2207.

Rochon P.A., Tu J.V., Anderson G.M., et al. Rate of heart failure and 1-year survival for older people receiving low-dose β-blocker therapy after myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2000;356:639-644.

Sabatine M.S., Cannon C.P., Gibson C.M., for the CLARITY-TIMI 28 Investigators, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;352:1179-1189.

Stone G.W., Bertrand M.E., Moses J.W., et al. Routine upstream initiation vs deferred selective use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in acute coronary syndromes: the ACUITY Timing Trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 2007;297:591-602.

Thygesen K., Alpert J.S., White H.D., et al. Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J.. 2007;28:2525-2538.

Unal B., Critchley J.A., Capewell S. Explaining the decline in coronary heart disease mortality in England and Wales between 1981 and 2000. Circulation. 2004;109:1101-1107.

VALIANT (VALsartan In Acute myocardial iNfarction Trial) Investigators. Valsartan, captopril, or both in myocardial infarction complicated by heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction, or both. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2003;349:1893-1906.

Van de Werf F., Bax J., Betriu A., et al. The task force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J.. 2008;29:2909-2945.

Yusuf S., Sleight P., Pogue J., et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) Study Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2000;342:145-153.

Montalescot G., Wiviott S.D., Braunwald E., et al. Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (TRITON-TIMI 38): double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:723-731.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Unstable Angina and NSTEMI. The Early Management of Unstable Angina and Non-ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. London: NICE; 2010. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG94