CHAPTER 36 Coronary Artery Aneurysms

DEFINITION

Coronary artery aneurysm (CAA) is defined as a dilation more than 1.5 times the diameter of adjacent normal segments.1 It was first described by Morgagni in 17812,3; the first case report was published by Bougon in 1812,1,4 and the first documented case with angiography was published by Munker in 1958.5,6 Before the advent of coronary angiography, CAAs were detected primarily at postmortem examination; however, most cases today are incidental findings on angiography.

PREVALENCE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

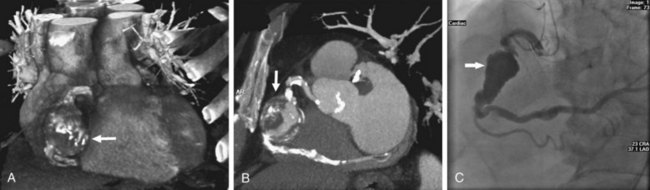

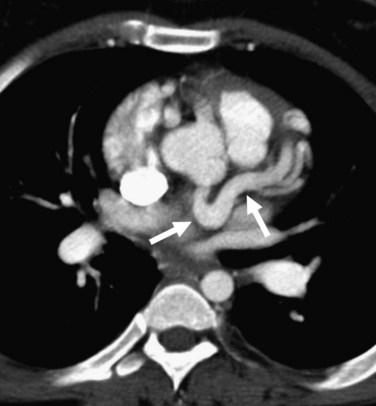

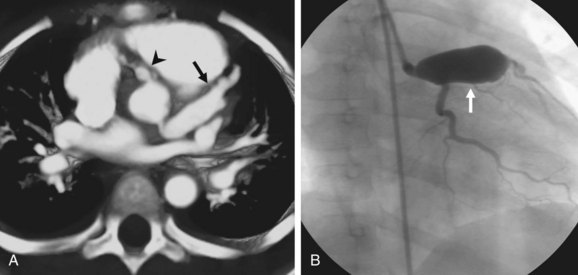

The reported incidence of CAAs ranges from 0.2% to 4.9% among patients undergoing evaluation for coronary disease.1,5 They occur predominantly in men at a ratio of almost 3 : 1.4 CAAs are predominantly caused by atherosclerosis (52%). They may be single or multiple, may be focal or diffuse, and can involve various segments of the coronary circulation. They most commonly involve the right coronary artery (Fig. 36-1) followed by the left anterior descending (Fig. 36-2) and the left circumflex (Fig. 36-3) arteries.4

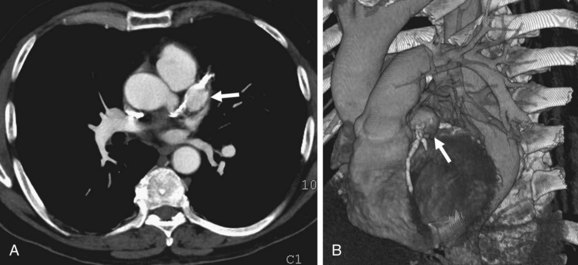

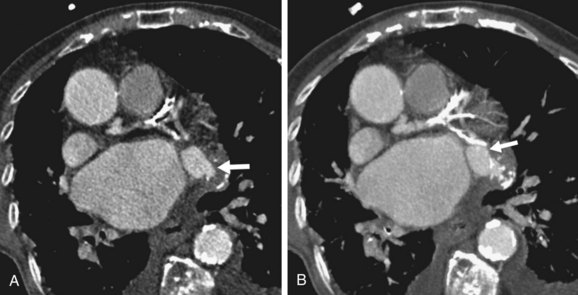

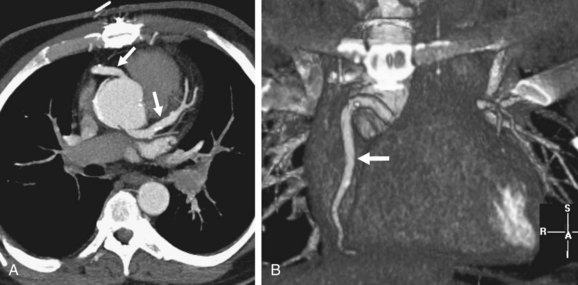

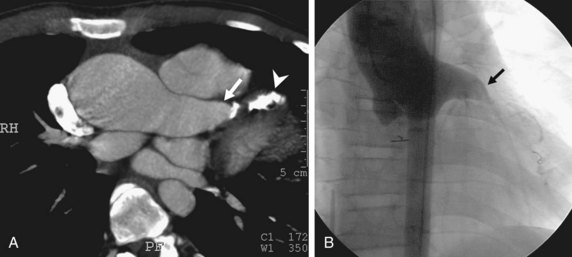

Atherosclerotic aneurysms of the left main coronary artery are rare, but have been reported.7 Other important etiologies include congenital (17%), mycotic-embolic (11%), dissecting (11%), syphilitic (4%), and unclassified (5%).4 Although most cases worldwide are secondary to atherosclerosis, systemic inflammatory diseases such as Takayasu arteritis (Fig. 36-4) and the mucocutaneous lymph node syndromes of Kawasaki disease (Fig. 36-5) account for many cases in East Asia.8 Modern interventional techniques have also resulted in iatrogenic causes of CAAs. In the current era of percutaneous intervention, CAAs can be seen secondary to balloon angioplasty or stent deployment.9 The increasing use of coronary artery bypass grafting techniques has resulted in numerous reports of saphenous vein graft aneurysms (Fig. 36-6), although they remain uncommon.

Although CAAs may be found at any age, atherosclerotic subtypes are predominant later in life, whereas congenital (Figs. 36-7 and 36-8), mycotic-embolic, and dissecting types are found in younger age groups. Multiple CAAs in childhood and adolescence are usually late complications of Kawasaki disease (Fig. 36-9).10

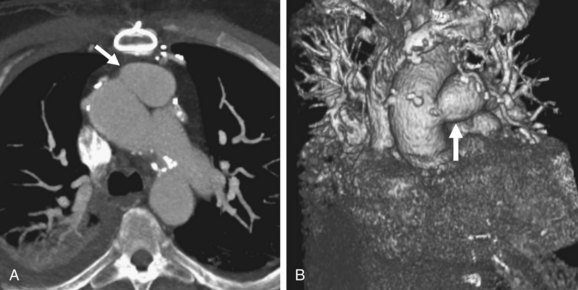

CAAs are associated with systemic syndromes of hyperlipidemia and hypertension, but a correlation between aneurysm size and cardiac risk factors has not been proven.8,11 They have been shown to be more prevalent in patients with aortic aneurysms, which is corroborated by studies showing increased diameter indices of iliac arteries in patients with known CAA (Fig. 36-10).12

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

CAA is likely a variant of obstructive coronary artery disease in most cases; however, its pathogenesis has not been fully elucidated. Systemic hypertension, inflammatory stimuli such as tobacco or increased inflammatory response in the vessel wall, hyperhomocysteinemia, and chronic Epstein-Barr virus infection are implicated as etiologic factors. Genetic predisposition or gene disruption, interference with normal cross-linking of collagen, and activation of matrix metalloproteinases are all possible factors implicated in the weakening of the vessel wall in aneurysmal disease.8

MANIFESTATIONS OF DISEASE

Clinical Presentation

Presentations of CAAs are almost always suggestive of coronary ischemia requiring further ischemic evaluations, which generally detect the anomaly.3 Because CAAs are usually associated with obstructive atherosclerotic coronary disease, the clinical course depends on the severity of the associated stenosis,3 and can culminate in myocardial infarction or sudden death complicated by thrombus formation, distal embolization, shunt formation, or rupture.8 Exercise-induced angina pectoris or myocardial infarction may occur without significant coronary artery stenosis, however, and is usually attributed to distal microembolization of thrombus or microcirculatory dysfunction reflected by depressed coronary flow reserve in these patients.8,13 The natural history and prognosis of this entity are unknown; however, observational studies have documented development of myocardial infarction with angiographically documented occlusion of the involved aneurysmal vessel.3,5

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

Although CAAs are commonly an incidental finding, rare cases of giant coronary aneurysms can cause a significant protrusion of the heart border on chest x-rays14 or compression of cardiac chambers on echocardiography.15

Angiography

CAAs complicated by rupture or fistula formation (into a cardiac chamber) may create a continuous murmur on auscultation. The standard of reference for the diagnosis of CAAs is via a percutaneous approach with coronary angiography, which provides information about the size, shape, location, and number of aneurysms.8 Evaluation and serial follow-up may require other diagnostic methods. Intravascular ultrasound further allows for distinguishing true and false aneurysms.8

Cardiac CT angiography enables a noninvasive alternative for initial diagnosis and follow-up. Its tomographic capabilities enable improved visualization of extraluminal pathology and important surrounding extravascular anatomy.16 In suspected aneurysmal disease, standard cardiac CT angiography protocols are performed. Prospective ECG gating or retrospective ECG gating can be performed with dose modulation using 120 kV and 800 mAs (effective). An intravenous contrast agent is administered: 75 to 100 mL of 350 to 375 mg I/mL contrast agent, followed by 30 mL of saline. Studies are typically performed with an automated bolus tracking technique with the region of interest placed in the ascending aorta or with a timing bolus. Studies performed with retrospective gating are reconstructed at 10% intervals of the cardiac cycle. Although standard multiplanar reconstructions are performed for diagnosis, volume rendered reconstruction techniques can be helpful in preoperative planning.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Medical

The management of CAAs can be medical, percutaneous, or surgical. If the patient is asymptomatic, and medical therapy is chosen, the regimen should include antiplatelet therapy with or without anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolic complications.3,16 Risk factor modification with statins and antihypertensives may be beneficial in slowing the progression of atherosclerotic aneurysmal disease, but this has not been established.

Surgical/Interventional

Surgery is generally advised for large aneurysms associated with significant coronary stenosis, which includes ligation and bypass of the aneurysm.17 Percutaneous approaches are increasingly being reported for moderate-sized aneurysms with associated coronary stenosis via polytetrafluoroethylene-covered balloon-expandable18 or self-expandable stents.19 Even complicated aneurysms with fistulization, when appropriate, can be addressed percutaneously with coil embolization (Fig. 36-11).20

Dell’Amore A, Sanna S, Botta L, et al. Giant atherosclerotic aneurysm of left internal mammary artery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:557-558.

Kobulnik J, Hutchison SJ, Leong-Poi H. Saphenous vein graft aneurysm masquerading as a left atrial mass: diagnosis by contrast transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 20, 2007. 1414.e1-1414.e 4

1 Swaye PS, Fisher LD, Litwin P, et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1983;67:134-138.

2 Morgagni JB. De sedibus et causis morborum per anatoment indagatis. Tomus Primus Liber II. 1761. Epist 27, Articlo 28. Venetiis

3 Rath S, Har-Zahav Y, Battler A, et al. Fate of nonobstructive aneurysmatic coronary artery disease: angiographic and clinical follow-up report. Am Heart J. 1985;109:785-791.

4 Daoud AS, Pankin D, Tulgan H, et al. Aneurysms of the coronary artery: report of ten cases and review of literature. Am J Cardiol. 1963;11:228-237.

5 Dagalp Z, Pamir G, Alpman A, et al. Coronary artery aneurysms: report of two cases and review of the literature. Angiology. 1996;47:197-201.

6 Wilson CS, Weaver WF, Forker AD, et al. Bilateral arteriosclerotic coronary arterial aneurysms successfully treated with saphenous vein bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 1975;35:315-318.

7 Gowda RM, Dogan OM, Tejani FH, et al. Left main coronary artery aneurysm. Int J Cardiol. 2005;105:115-116.

8 Pahlavan PS, Niroomand F. Coronary artery aneurysm: a review. Clin Cardiol. 2006;29:439-443.

9 Bavry AA, Chiu JH, Jefferson BK, et al. Development of coronary aneurysm after drug-eluting stent implantation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:230-232.

10 Markis JE, Joffe DC, Cohn PF, et al. Clinical significance of coronary ectasia. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:217-222.

11 Baman TS, Cole JH, Devireddy CM, et al. Risk factors and outcomes in patients with coronary artery aneurysms. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1549-1551.

12 Kahraman H, Ozaydin M, Varol E, et al. The diameters of the aorta and its major branches in patients with isolated coronary artery ectasia. Tex Heart Inst J. 2006;33:463-468.

13 Akyurek O, Berkalp B, Sayin T, et al. Altered coronary flow properties in diffuse coronary artery ectasia. Am Heart J. 2003;145:66-72.

14 Tanabe M, Onishi K, Hiraoka N, et al. Bilateral giant coronary aneurysms diagnosed non-invasively by dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cardiol. 2004;94(2-3):341-342.

15 McGlinchey PG, Maynard SJ, Graham AN, et al. Giant aneurysm of the right coronary artery compressing the right heart. Circulation. 2005;112:e66-e67.

16 Plehn G, van Bracht M, Zuehlke C, et al. From atherosclerotic coronary ectasia to aneurysm: a case report and literature review. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2006;22:311-316.

17 Harandi S, Johnston SB, Wood RE, et al. Operative therapy of coronary arterial aneurysm. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1290-1293.

18 Lee MS, Nero T, Makkar RR, et al. Treatment of coronary aneurysm in acute myocardial infarction with Angio-Jet thrombectomy and JoStent coronary stent graft. J Invasive Cardiol. 2004;16:294-296.

19 Burzotta F, Trani C, Romagnoli E, et al. Percutaneous treatment of a large coronary aneurysm using the self-expandable Symbiot PTFE-covered stent. Chest. 2004;126:644-645.

20 Jo SH, Choi YJ, Oh DJ, et al. Coronary artery fistula with a huge aneurysm treated by transcatheter coil embolization. Circulation. 2006;114:e631-e634.

FIGURE 36-1

FIGURE 36-1

FIGURE 36-2

FIGURE 36-2

FIGURE 36-3

FIGURE 36-3

FIGURE 36-4

FIGURE 36-4

FIGURE 36-5

FIGURE 36-5

FIGURE 36-6

FIGURE 36-6

FIGURE 36-7

FIGURE 36-7

FIGURE 36-8

FIGURE 36-8

FIGURE 36-9

FIGURE 36-9

FIGURE 36-10

FIGURE 36-10

FIGURE 36-11

FIGURE 36-11