198 Conversion Disorder, Psychosomatic Illness, and Malingering

• Somatization disorder, conversion disorder, and hypochondriasis are psychologic reactions to stressful circumstances that are neither intentional nor planned.

• Malingering and factitious disorders involve deliberate actions of deceit of which the patient is aware.

• Somatoform conditions feature complaints and symptoms that cannot be attributed to medical illness.

• Emergency department evaluation of patients with suspected somatoform disorders should focus on the search for a medical cause of the reported symptoms and exclusion of life-threatening illness.

• Identification and appropriate referral of patients with somatoform illness are secondary objectives of the emergency department encounter.

• As with other psychiatric and medical diagnoses, thorough documentation is required when somatization is suspected.

Acknowledgment and thanks to Dr. Marshall for his work on the first edition.

Epidemiology

Somatoform conditions include the following diagnoses: somatization disorder, conversion disorder, somatoform pain disorder, hypochondriasis, body dysmorphic disorder, and undifferentiated somatoform illness. The boundaries between these disorders can be subtle, and it has recently been proposed that four of these conditions—somatization disorder, somatoform pain disorder, hypochondriasis, and undifferentiated somatoform illness—should be reclassified under a single common rubric called complex somatic symptom disorder (CSSD).1 Further classification of somatoform disorders is continually evolving as research better defines their distinctive characteristics.1–3

The reported prevalence of somatoform conditions ranges from 50% to 65% in ambulatory settings.4,5 When definitions are narrowed to include only patients meeting strict diagnostic criteria for somatization disorder, the lifetime prevalence drops to less than 3%.6 Accurate classification is difficult because some patients exhibit somatoform symptoms in the presence of demonstrable medical illness.

Definitions

Somatization disorder is characterized by the presence of multiple chronic distressing somatic symptoms that are not medically explained. Patients with this condition tend to be highly anxious about their symptoms, even in the face of evidence that their condition is not medically serious. In the draft of the upcoming Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), this condition has been renamed CSSD.1

Hypochondriasis is preoccupation with or excessive fear of illness despite negative testing and reassurance from a health care professional. Hypochondriasis is more common than somatization disorder and has a prevalence of 4% to 9% in general medical practice.7 It peaks in men in the fourth decade and in women in the fifth, with no significant predilection by gender. Hypochondriasis is increasingly being described in geriatric populations.8 It has been renamed the “predominant health anxiety” subtype of CSSD in the proposed draft of DSM-V.1

Somatoform pain disorder, an important and particularly challenging somatoform illness, is characterized by somatoform symptoms that are manifested predominantly as pain. In the proposed draft of DSM-V, this condition is reclassified as the “predominant pain” subtype of CSSD.1

Conversion disorder is a condition in which patients complain of sensory or motor symptoms as a manifestation of stress or unconscious conflict that cannot be attributed to a pathophysiologic process. Conversion disorder is more common in women and members of lower socioeconomic groups. Its onset typically begins in adolescence, and it follows a discontinuous course. Conversion disorder has also been observed in military, mass casualty, and industrial accident settings without a female preponderance of the disorder.9 Estimates of prevalence vary considerably as a result of inconsistent classifications and definitions of the disorder.

Body dysmorphic disorder is characterized by a preoccupation with an imagined defect in physical appearance. Although it is currently classified under somatoform disorders, body dysmorphic disorder more closely resembles obsessive-compulsive disorder and as a result may be moved to the anxiety disorders section of the DSM-V.1 This disorder is commonly encountered by primary care providers, plastic surgeons, and the body enhancement industry.

Factitious disorders, including malingering, feature deliberate manufacturing of symptoms or illness. The combined prevalence of all factitious disorders ranges from 1% to 5%, again with a female preponderance. The term Munchausen syndrome (after the famous 18th-century raconteur Baron von Munchausen) is reserved for chronic or “career” medical imposters, and it represents the extreme form of the disorder. However, cases of Munchausen syndrome tend to involve male patients.10

Malingering and symptom exaggeration are probably underreported. In one study, “39% of mild head injury, 35% of fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue, 31% of chronic pain, 27% of neurotoxic, and 22% of electrical injury claims resulted in diagnostic impressions of probable malingering.”11 Malingering is most often exhibited by patients who are either trying to avoid an unpleasant circumstance, such as military duty or a prison term, or attempting to secure some form of compensation, such as occupational health or personal injury plaintiff claims. Malingering can result in criminal charges.12

Factitious disorder by proxy or Munchausen syndrome by proxy deserves special mention because it may represent a form of child abuse. It is typically defined as the intentional production or feigning of physical or psychiatric illness in a child by the child’s guardian, although it has also been reported in caregivers of geriatric patients. Factitious disorder by proxy can be active (symptom producing) or passive (neglect). Munchausen syndrome by proxy is rare and occurs in roughly 2.8 per 100,000 children younger than 1 year and 0.5 per 100,000 children younger than 16 years.13 As with the other factitious illnesses, the deceptive nature of the disorder makes it extremely difficult to detect and study.

Pathophysiology

Somatoform illnesses represent emotional stress experienced as physical symptoms. Both somatization and hypochondriasis are commonly associated with depression and anxiety, and somatization is classified as a potential initial symptom of depression.14 This strong association with depressive disorders has led to the practice of treating somatization with antidepressant medications. Hypochondriasis and depression coexist in roughly 40% of cases. Twenty percent of patients with hypochondriasis have a diagnosis of panic disorder, and 10% have an obsessive-compulsive disorder.15 As the number of reported physical symptoms rises in patients with somatoform illness, the likelihood of an underlying psychiatric disorder increases proportionately.16

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic Features

Somatization is exhibited by patients who are chronically and persistently “sick” with numerous vague complaints and symptoms involving many organ systems; review of systems is often globally “positive.” Patients’ symptoms are distressing to them, and their suffering is authentic even if medically inexplicable. Patients maintain a very strong conviction of illness despite multiple negative diagnostic work-ups, hospital admissions, specialist referrals, and surgical procedures. An example of the breadth of symptoms associated with somatoform disorders can be seen in the diagnostic criteria listed in Box 198.1.

Box 198.1

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision) Criteria for Somatization Disorder

1. Pain in at least four distinct locations or circumstances (e.g., headache, backache, chest pain, dysuria, dyspareunia)

2. Two or more gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, but not pain)

3. One or more sexual dysfunction symptoms (e.g., impotence, lack of libido, menorrhagia, but not pain)

4. One or more neurologic conversion symptoms (also see Box 198.2) (e.g., paresthesia, paralysis, ataxia, blindness, pseudoseizure)

Adapted from American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Conversion disorder, in contrast to somatization disorder, is the acute, often episodic onset of one symptom or sign involving limited body parts or organ systems. Complaints are generally sensory or motor in nature and often occur in response to an identified stressor. Unlike malingering or factitious disorders, the malady is not consciously feigned or deliberate. Examples of conversion disorder typically seen in the ED include pseudoseizures, altered mental status, paralysis, and movement disorders.17 Other common conversion symptoms are presented in Box 198.2.

La belle indifférence, a seemingly incongruous disinterest in one’s illness, is classically associated with conversion reactions. However, la belle indifférence may be seen with organic disease states such as stroke. La belle indifférence should not be used alone to differentiate between conversion and organic disorders.18

Patients who malinger and those who have factitious disorder tend to limit themselves to exaggerations of symptoms of a previously diagnosed illness or to symptoms that are difficult to investigate and disprove; examples include pain of any variety, psychiatric conditions such as suicidality, and the pseudoneurologic symptoms of tingling, amnesia, and seizures. Less commonly, patients with factitious disorder inflict injury or disease on themselves. Deliberate misuse of medications such as hypoglycemic agents has been described in health care workers.10

Unlike the somatoform disorders, malingering and factitious behavior involve feigned illness. Even though they are aware of their deception, patients with factitious disorder (unlike malingerers) are helpless to control the behavior.19 To illustrate the differences among somatoform disorder, factitious disorder, and malingering, one can use the example of nonepileptic or pseudoseizures, which can be seen in each condition. A patient with a somatoform disorder suffers a nonvolitional convulsion in response to a psychologic stressor, a patient with factitious disorder has an uncontrollable compulsion to feign a nonepileptic convulsion to gain attention and the sick role, and a patient who malingers feigns a convulsion as part of a ruse to achieve a specific end. What sets malingering apart from factitious disorder is the patient’s intentional pursuit of an identifiable, tangible goal or gain.20

Victims of Intimate Partner Violence

Among patients who tend to use emergency care frequently, an important subgroup consists of victims of intimate partner violence (see Chapter 93). Intimate partner violence results in high levels of psychologic stress for the victim. Many of these patients repeatedly seek care in the ED with somatoform behavior.21 Physicians must screen for ongoing abuse when new or recurrent physical symptoms cannot be attributed to a medical condition. Just as with current abuse, patients with a past history of physical, sexual, or psychologic abuse also tend to use medical services more frequently.

Differential Diagnosis and Testing

Classic findings can make one suspect a somatoform illness; however, such behavior is insufficient for psychiatric diagnostic criteria. Synopses of the characteristics of somatoform disorders can be found in Table 198.1. It is useful to categorize these illnesses as nondeliberate (somatization, conversion disorder, and hypochondriasis) and deliberate (factitious disorders and malingering).

| DISORDER | HALLMARKS |

|---|---|

| Somatization disorder |

Concerns about making the diagnosis of a somatoform illness should not preclude a thorough ED evaluation because many medical conditions can be mistaken for somatization, particularly when the findings are atypical. Box 198.3 provides examples of medical conditions that can mimic somatoform behavior.

As a general rule, patients with nondeliberate somatoform illness acquiesce to invasive diagnostic testing, whereas those with factitious disorders and malingerers are more reluctant. The presence of two or more of the following features is suggestive of malingering behavior: mention of a medicolegal context of the visit, discrepancy between subjective and objective assessment of the degree of stress and disability, poor compliance with evaluation and treatment, and antisocial personality disorder.19 Malingering is very difficult to prove, even in the presence of high clinical suspicion and deliberate investigation, and surveillance of the patient is often required.22 Determination of malingering is usually the purview of specialists such as neuropsychologists.

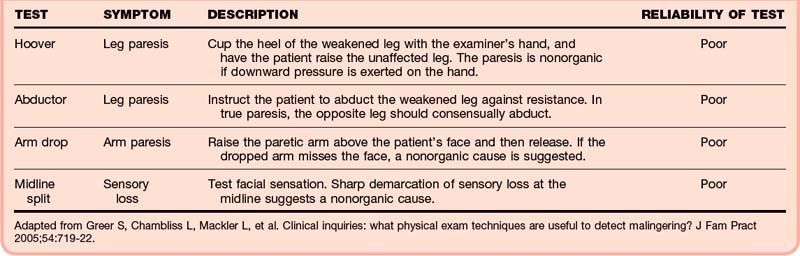

Various maneuvers are purported to assist in identifying factitious symptoms, as shown in Table 198.2. Waddell’s “behavioral responses to examination,” as applied to a chief complaint of back pain, are one example. Although the Waddell signs provide a compelling method of detecting feigned illness, the predictive value of such maneuvers is generally poor and correlates with an unfavorable treatment outcome.23

Table 198.2 Physical Examination Maneuvers Purported to Differentiate Factitious from Organic Conditions

Tests for factitious paralysis have also been proposed but are similarly nonspecific.24 The abductor test is one such test: with true paresis, the unaffected leg abducts when the patient attempts to abduct the affected leg against resistance. The Hoover test involves placing the examiner’s hand under the “weakened” lower extremity and asking the supine patient to raise the unaffected leg; downward pressure with the affected leg is considered positive for feigned paralysis. Prudent caution is warranted in the interpretation of any diagnostic maneuver that is infrequently performed.

Treatment

No specific treatment of nondeliberate somatoform illness exists. Psychiatric comorbid conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse should be addressed. Cognitive behavioral therapy has shown promise in the minority of patients willing to be referred.25,26

Follow-Up and Next Steps in Care

It is not generally recommended that a patient with a somatoform illness be confronted. Instead, the patient should be reassured that the symptoms do not represent an imminent threat. Even in cases of malingering, neuropsychologists rarely confront patients; most use descriptive terminology rather than the diagnosis “malingering.”27

Dula D, DeNaples L. Emergency department presentation of patients with conversion disorder. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:120–123.

Greer S, Chambliss L, Mackler L, et al. Clinical inquiries: what physical exam techniques are useful to detect malingering? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:719–722.

Mendelson G, Mendelson D. Malingering pain in the medicolegal context. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:423–432.

Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, et al. La belle indifférence in conversion symptoms and hysteria: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:204–209.

1 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM V (Draft) [Internet]. 5th ed http://www.dsm5.org/Documents/Somatic/Somatic%20Symptom%20Disorders%20description%20January%2014%202011.pdf, 2011. Cited Jan 20, 2011. Available at

2 Mayou R, Kirmayer LJ, Simon G, et al. Somatoform disorders: time for a new approach in DSM-V. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:847–855.

3 Löwe B, Mundt C, Herzog W, et al. Validity of current somatoform disorder diagnoses: perspectives for classification in DSM-V and ICD-11. Psychopathology. 2008;41:4–9.

4 Katon WJ, Walker EA. Medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):15–21.

5 Kroenke K, Price RK. Symptoms in the community. Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2474–2480.

6 Kirmayer LJ, Robbins JM. Three forms of somatization in primary care: prevalence, co-occurrence, and sociodemographic characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:647–655.

7 Fink P, Ørnbøl E, Toft T, et al. A new, empirically established hypochondriasis diagnosis. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1680–1691.

8 Monopoli J. Managing hypochondriasis in elderly clients. J Contemp Psychother. 2005;35:285–300.

9 Ford CV, Folks DG. Conversion disorders: an overview. Psychosomatics. 1985;26:371–374. 380–3

10 Krahn LE, Li H, O’Connor MK. Patients who strive to be ill: factitious disorder with physical symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1163–1168.

11 Mittenberg W, Patton C, Canyock EM, et al. Base rates of malingering and symptom exaggeration. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2002;24:1094–1102.

12 Mendelson G, Mendelson D. Malingering pain in the medicolegal context. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:423–432.

13 McClure RJ, Davis PM, Meadow SR, et al. Epidemiology of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, non-accidental poisoning, and non-accidental suffocation. Arch Dis Child. 1996;75:57–61.

14 Posse M, Hällström T. Depressive disorders among somatizing patients in primary health care. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98:187–192.

15 Barsky AJ, Wyshak G, Klerman GL. Psychiatric comorbidity in DSM-III-R hypochondriasis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:101–108.

16 Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care. Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:774–779.

17 Dula DJ, DeNaples L. Emergency department presentation of patients with conversion disorder. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2:120–123.

18 Stone J, Smyth R, Carson A, et al. La belle indifférence in conversion symptoms and hysteria: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:204–209.

19 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV-TR fourth edition, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

20 Kalivas J. Malingering versus factitious disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1108.

21 Abbott J. Injuries and illnesses of domestic violence. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:781–785.

22 LoPiccolo CJ, Goodkin K, Baldewicz TT. Current issues in the diagnosis and management of malingering. Ann Med. 1999;31:166–174.

23 Fishbain DA, Cole B, Cutler RB, et al. A structured evidence-based review on the meaning of nonorganic physical signs: Waddell signs. Pain Med. 2003;4:141–181.

24 Greer S, Chambliss L, Mackler L, et al. Clinical inquiries. What physical exam techniques are useful to detect malingering? J Fam Pract. 2005;54:719–722.

25 Barsky AJ, Ahern DK. Cognitive behavior therapy for hypochondriasis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1464–1470.

26 Thomson AB, Page LA. Psychotherapies for hypochondriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2007. CD006520

27 Slick DJ, Tan JE, Strauss EH, et al. Detecting malingering: a survey of experts’ practices. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19:465–473.