CHAPTER 20 CONVERSION AND DISSOCIATION SYNDROMES

Social historians have confidently asserted that conversion hysteria has disappeared from clinical practice, to be replaced by syndromes characterized by fatigue and other medically unexplained disorders.1,2 Although the florid manifestations of hysteria seen in the days of Pierre Janet are less common in the 21st century, the evidence from clinical practice is that patients with conversion disorders are not infrequently encountered by neurologists in both outpatient and inpatient settings.3 Indeed, it has been shown that symptoms considered “functional,” “psychogenic,” “medically unexplained,” or “hysterical” account for up to one third of new referrals to neurology outpatient departments.3,4 In a German survey, Rief and colleagues5 found a 2% base rate of unexplained paralysis or localized weakness in the population and a 5% base rate for “impaired coordination or balance” and “unpleasant numbness or tingling sensations.” In this chapter, the diverse manifestations of conversion and dissociation disorders are described, and the advances in approaches to treatment are outlined.

PROBLEMS WITH DEFINITION

There are a number of problems with the definition of the conversion disorder. First, physical disorder must be excluded, but the rate of neurological comorbidity is known to be high in patients with conversion disorder,6 and distinguishing which symptoms are accounted for by organic disease and which are not can be difficult. Second, it is stated that6a a temporal association between a psychological stressor and the onset on the disorder should be identified, but in practice, this is often impossible to establish, and doing so depends to a large extent on the skill of the interviewing physician. Finally, by definition, the process should be unconsciously mediated, but in practice it is difficult (some authorities would say impossible) to distinguish between symptoms that are not consciously produced and those that are intentionally manufactured. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition,6a provides no criteria for distinguishing conscious from unconscious intent, and many authors have argued that the criteria of whether the patients are consciously aware of producing these symptoms should be excluded from the diagnosis of conversion disorder.7

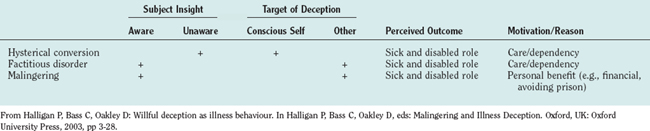

A question often asked by neurologists, when confronted with a patient with unexplained loss of function of the limb, is “How do I distinguish between conversion disorder, factitious disorder, and malingering?” For the reasons just described, it is difficult to answer this question, because a patient’s “awareness” or “motivations” are not knowable. Various attempts have been made to provide adequate definitions, but all have their limitations (Table 20-1). Attempts to “demedicalize” this complex diagnostic field have introduced the concepts of “free will” and patient choice,8 and motor symptoms of hysteria have been discussed as “disorders of willed action.”9 Neurologists require considerable skills to diagnose and manage these conditions, which can be among the most taxing in the speciality.10

The term conversion is conventionally applied to somatic symptoms, whereas if the symptom is psychological (e.g., a loss of memory or an external hallucination) rather than physical (e.g., a loss of power), it is regarded as dissociative. Dissociation has attracted considerable interest, and in a major review of the topic, Holmes and colleagues (2005)11 drew a distinction between two qualitatively distinct, clinically relevant forms of dissociation, labeled compartmentalization (type 1) and detachment (type 2)12 (Table 20-2). Compartmentalization phenomena are characterized by impairment in the inability to control processes or actions that would usually be amenable to such control and that are otherwise functioning normally. This category encompasses unexplained neurological symptoms (including dissociative amnesia) and benign phenomena such as those produced by hypnotic suggestion. In contrast, detachment phenomena are characterized by an altered state of consciousness associated with a sense of separation from the self, the body, or the world. Depersonalization, derealization, and out-of-body experiences constitute archetypal examples of detachment in this account. Evidence suggests that these phenomena are generated by a common pathophysiological mechanism involving the top-down inhibition of limbic emotional processing by frontal brain systems. Although these two types of dissociation are typically conflated, evidence suggests that different pathological mechanisms may be operating in each case.

TABLE 20-2 Classification of Two Types of Pathological Dissociation

| Type 1 Dissociation (Compartmentalization) | Type 2 Dissociation (Detachment) |

|---|---|

| Conversion disorders | Depersonalization/derealization |

| Dissociative amnesia | Peritraumatic dissociation |

| Dissociative fugue | Out-of-body experiences |

| Dissociative identity disorder | Autoscopy (?) |

From Brown RJ: The cognitive psychology of dissociative states. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 2002; 7:221-235.

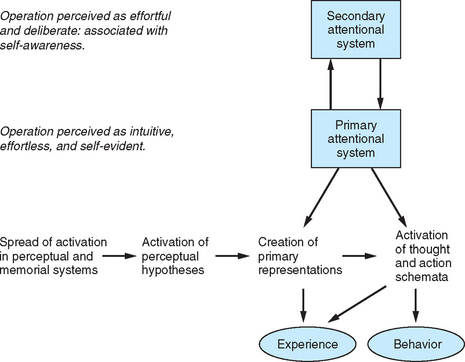

Support for the compartmentalization model comes from psychophysiological research, which suggests that psychogenic illness is associated with a deficit in attentional, conscious processing and the preservation of preattentive, preconscious processes. According to Brown,13 there is very little difference between “negative” symptoms, such as sensory loss and paralysis, and “positive” symptoms, such as tremor and dystonia, in terms of basic underlying mechanisms. According to this view, all symptoms result from a loss of normal high-level attentional control over low-level processing systems; in this sense, all symptoms can be viewed as involving a form of compartmentalization. In each case, the “dissociation” between high- and low-level control results from the repetitive reallocation of high-level attention onto “rogue representations” in memory, causing low-level attention to misinterpret this stored information as an account of current rather than past processing activity. The model is shown diagrammatically in Figure 20-1.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In 1976, an editorial in the British Medical Journal suggested that hysteria was “virtually a historical curiosity in Britain.”14 Despite this assertion, the published evidence suggests that it is as common as other disabling conditions such as multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia.15 In a comprehensive review of the literature, Akagi and House15 concluded that the lowest prevalence data suggested a rate of about 50 per 100,000 for cases of conversion disorder known to health services at any one time, with perhaps twice that number affected over a 1-year period. These prevalence studies suggest that the burden of disability associated with chronic hysteria is far higher than a typical practicing psychiatrist might expect or than is reflected in standard textbooks of psychiatry or clinical neurology.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Conversion Disorder

Motor Symptoms

The Clinical Approach

The physician must not only rule out neurological disorder with the usual methods of history taking, examination, and investigation, but at the same time seek the “positive signs” of hysteria and establish that there is an appropriate psychosocial background for the emergence of medically unexplained symptoms. Since the mid-1990s, diagnostic procedures have improved, and the availability of noninvasive, accurate imaging has drastically reduced the rates of organic pathology that remains undetected in patients with diagnoses of hysteria. Indeed, several studies have reported rates of misdiagnosis of between 0% and 4% in regional and tertiary neurological centers,16 which suggests that a diagnosis of conversion disorder can be made relatively confidently and accurately. In the following section, the process of diagnosis is briefly outlined through the history, examination, and investigation.

The History

Previous Unexplained Symptoms.

There is accumulating evidence that the more unexplained symptoms the patient has, the more likely the primary symptom is to be unexplained.17 In one study of patients with medically unexplained motor symptoms, additional unexplained symptoms, including paresthesia (65%), pseudo-epileptic seizures (23%), and memory impairment (20%), were reported.18 It is, therefore, often useful when conversion disorder is being considered as a diagnosis to obtain a printout of the patient’s history from the primary care physician. This may reveal repeated presentations to different specialists, as well as a history of repeated surgical procedures, particularly without clear evidence of pathology.

Psychiatric Comorbidity.

Rates of depression (38% to 50%) and anxiety (10% to 16%) have been identified in a number of studies. In one small prospective controlled study, there was a fourfold increase in depression among patients with conversion disorder in comparison with matched controls with similar organic disability.19

Recent Life Events or Difficulties.

An increased number of life events in the year preceding symptom onset have been recorded in small controlled studies of unexplained motor symptoms20 and pseudoseizures.21 More recent evidence suggests that when patients are interviewed carefully, some report symptoms of panic just before the onset of, for example, functional weakness (J. Stone, personal communication, 10.2.2006). Judicious questions about sensations of sweating, dizziness, and breathing difficulty may reveal these somatic symptoms of anxiety, which may also be reported before the onset of sensory symptoms (see later section on sensory symptoms).

Secondary Gain/Litigation.

This is a complex issue, but impending litigation has been described in a number of studies of patients with unexplained motor symptoms and tremor.18,21

Neurological Comorbidity.

In one study in the United Kingdom, 42% of patients with unexplained motor symptoms had a comorbid neurological disease and, interestingly, one half of these had a peripheral origin.18 Epilepsy is believed to coexist in a significant percentage of patients with nonepileptic seizures.22

History from Relative/Informant.

There is a considerable amount of evidence to suggest that the observations and attitudes of caretakers may be important in the perpetuation of medically unexplained symptoms, especially motor conversion symptoms. For example, Davison and associates23 found caretakers to be ill informed and dissatisfied with the advice they had received from doctors about their relatives’ diagnosis and disabilities.

The Examination and Diagnostic Discrepancies

Give-way weakness is often used as a diagnostic test of hysterical paralyses, but it is unreliable. Unilateral functional weakness of a leg, if severe, tends to produce a characteristic gait in which the leg is dragged behind the body as a single unit, like a sack of potatoes. The hip is either held in external or internal rotation so that the foot points inward or outward. The most impressive quantitative discrimination to date between hysterical and neurological weakness is reported in a study of Hoover’s sign—the involuntary extension of hysterically paralyzed leg when the “good leg” is flexing against resistance. Ziv and colleagues24 demonstrated a clear difference in the pattern of response between neurological and psychogenic patient groups. It should be borne in mind, however, that the patient may have both a functional disorder and an organic disorder.25

Individual Symptoms

Paralyses

Hysterical paraplegia has been described,26 and both spinal and orthopedic surgeons, as well as rehabilitation specialists and neurologists, should be alert to the development of this disorder in their patients.27 These patients have the potential to use considerable health care resources.28

Abnormal Movements

Psychogenic movement disorders are believed to account for 1 per 30 patients attending a movement disorder clinic21 and have been the subject of a book.29 Since the mid-1980s, a number of case series of patients with psychogenic dystonia have been reported. Fahn and Williams30 described 21 cases in 1988, and Lang31 subsequently described 18 more. Clinical features that suggest a psychogenic movement disorder are shown in Table 20-3.

TABLE 20-3 Features Suggestive of a Psychogenic Movement Disorder

Adapted from Fahn S: Psychogenic movement disorders. In Marsden CD, Fahn S, eds: Movement Disorders: 3. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1995, pp 359-372.

In a systematic study of 103 patients with fixed dystonia, Schrag and associates (2004)32 found that 37% fulfilled criteria for psychogenic dystonia and 29% fulfilled criteria for somatization disorder, which is characterized by chronic, multiple, persistent, medically unexplained symptoms. Although many patients fulfilled strict criteria for a somatoform disorder/psychogenic dystonia, the diagnosis remained uncertain in a proportion of patients, and whether the disorder was primarily neurological or psychiatric remains an open question. Such patients require the services of a multidisciplinary team.

Seizures (Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures)

It is estimated that more than 25% of patients receiving a diagnosis of refractory epilepsy in a chronic epilepsy clinic do not have epilepsy.33 Although the population incidence of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNESs) may be only 4% that of epilepsy, PNES constitutes a large share of the workload of neurologists and of emergency and general physicians. A number of details in the patient’s history may suggest a diagnosis of PNES rather than epileptic seizures (Table 20-4).

TABLE 20-4 Details in Patients’ History That May Suggest a Diagnosis of Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures Rather Than Epileptic Seizures

| Feature in History | Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures | Epileptic Seizures |

|---|---|---|

| Manifestation at age <10 years | Unusual | Common |

| Change in symptoms | Occasional | Rare |

| Aggravation by AEDs | Occasional | Rare |

| Seizures in presence of physicians | Common | Unusual |

| Recurrent “status epilepticus” | Common | Rare |

| Multiple unexplained physical symptoms | Common | Rare |

| Multiple operations/invasive tests | Common | Rare |

| Psychiatric treatment | Common | Rare |

| Sexual and physical abuse | Common | Rare |

AED, antiepileptic drug.

Adapted from Reuber M, Elger C: Psychogenic non epileptic seizures: review and update. Epilepsy Behav 2003; 4:205-216.

PNESs can be distinguished from epileptic seizures: PNESs generally occur in the presence of an audience or when another person is close by. They may be precipitated by stress but more often seem to occur in response to the social setting. The fall to the ground is not usually abrupt, and movements may follow the fall with clutching, but the characteristic regular tonic-clonic sequence of epilepsy is not found. Tongue biting and incontinence of urine are rare in hysterical seizures, the corneal reflexes are preserved, and the plantar muscles are flexed, unless previously abnormal. Firm handling and pressure on the supraorbital nerves to the point of pain may arouse the patient. PNESs occur most often among epileptic patients or among others who have seen epileptic seizures. A few epileptic patients learn how to induce ictal discharges and can produce extra seizures. Although rarely available during a seizure, the electroencephalogram is generally abnormal in epilepsy and normal during hysterical seizures.22

It usually takes several years to arrive at the diagnosis of PNES, and 75% of patients (with no additional epilepsy) are treated with anticonvulsants initially. If PNES is not diagnosed and managed early, significant iatrogenic harm may occur. The outcome is not always favorable in these patients: in one study carried out at a mean of 11.9 years after manifestation and 4.1 years after diagnosis of PNES, 71% of patients continued to have seizures and 56% were dependent on Social Security. Outcome was better in patients with greater educational attainments, younger age at onset and diagnosis, attacks with less dramatic features, and fewer additional medically unexplained complaints.34

It has been reported that patients with PNES have a consistently different psychosocial profile from patients with motor conversion symptoms. In a prospective study of consecutive neurological inpatients with either motor conversion or pseudoseizures of recent onset, patients with PNES were younger, more likely to have both an emotionally unstable personality disorder and a worse perception of parental care, more likely to report incest, and more likely to have reported more life events in the 12 months before symptom onset than were patients with motor conversion symptoms.20

Sensory Symptoms

Sensory Disturbance

The clinical detection and localization of sensory dysfunction is probably one of the least reliable areas of the neurological examination. Sensory loss may involve one half of the entire body from head to toe or from right to left. It may affect the whole of a limb and characteristically has a glove or stocking distribution on the arms or legs or both. The sensory loss generally fails to fit in with known anatomical boundaries but conforms more with the patient’s concept of physiology and anatomy. Thus, hysterical sensory loss is likely to stop sharply at the midline, whereas nonhysterical sensory change only approaches the midline, inasmuch as at this point segmental nerves overlap by one or two centimeters on each side.

Unfortunately, these classic signs are often unreliable. Gould and coworkers35 found “psychogenic” features on sensory examination in more than one half of their neurological patient group, and diminished vibration sense over the affected part of the forehead was noted in 69 of 80 patients with neurological disorders.36 This study also revealed that “midline splitting” of sensory function was not helpful in determining whether there was an underlying neurological disorder. These clinical findings should clearly be interpreted with circumspection.

Hemisensory disturbances can often manifest as emergencies; sometimes the patient ascribes the symptoms to “a stroke,” in association with anxiety and panic and other physical symptoms of anxiety.37 These symptoms may be provoked by hyperventilation38 or hypnotic suggestion.39 The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these changes are not as yet understood. Toth40 described 34 patients with the “hemisensory syndrome,” in which patients present with hemisensory disturbance and intermittent blurring of vision in the ipsilateral eye (asthenopia) and sometimes ipisilateral hearing problems as well. Hemisensory symptoms are increasingly recognized in patients with chronic pain and in patients with reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

Visual Disturbances

Ophthalmologists have estimated that psychogenic visual disorders account for up to 5% of their practice.41 Simple observation of visually guided behavior sometimes reveals telling inconsistencies, particularly in the case of severe apparent visual loss. A number of reliable optometric techniques are available to support bedside tests and the diagnosis of psychogenic visual loss, field disturbance, or gaze abnormality (for more details, see Stone and Zeman16). Disabling hysterical blindness presents more difficulties. Evoked potential studies help demonstrate intact visual pathways.

PROGNOSIS

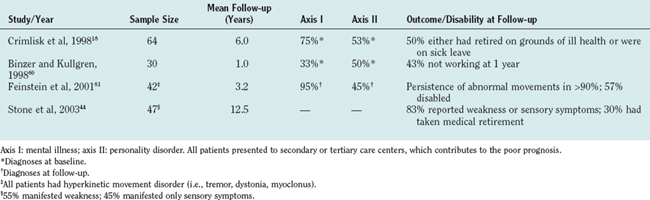

Outcome in published studies depends to some degree on the setting: tertiary referral centers tend to attract patients with chronic or intractable symptoms. Better outcomes appear to be associated with short or acute onset and early improvement. There is little chance of improvement once the symptoms have become chronic and enduring.42

The etiological implications accruing from follow-up studies43,44 are that a short history and young age are predictors of good outcome, whereas the presence of a personality disorder, chronicity of symptoms, receipt of disability benefits, and involvement with litigation predict poor recovery. Ron42 wrote an excellent recent review of this topic.

Patients with chronic motor symptoms (e.g., unilateral functional weakness), as well as those with sensory symptoms, appear to do particularly poorly. In particular, patients with unexplained motor symptoms who are referred to tertiary care centers continue to do very poorly after discharge. Despite the stability of the diagnosis, a pattern of multiple hospital referrals continues for many of these patients once they have been discharged from the tertiary care center. Interviews of patients conducted an average of 6 years after their original admission to a tertiary care center revealed that many continued to be referred to neurologists and other specialists but that subsequent psychiatric referral was rare.43 Many changed their primary care physician after discharge from the hospital, and a disproportionate number of repeated referrals was made by primary care physicians who had known their patients for less than 6 months. Psychological attribution of symptoms was rare, and many patients felt dissatisfied with the treatment they had received. Many were exposed to unnecessary iatrogenic harm. These consistent findings of very poor outcome after discharge from neurological outpatient and inpatient services in patients with both unexplained motor disorders and PNES suggest that every neurological service should have access to referral to specialist liaison psychiatry services. Such patients are often very difficult to treat and, because of their poor prognosis, should have a reasonable chance of obtaining early and appropriate management for their primary disorder.44,45 Without appropriate treatment, the prognosis is poor (Table 20-5).

MANAGEMENT

Resources

Before any discussion of treatment, it is important to consider the resources available to the neurologist to manage these patients. In contrast to disorders such as multiple sclerosis and schizophrenia, which have similar prevalences, there are no designated resources for patients with psychogenic disorders. Some neurologists may have no access whatsoever to mental health resources, whereas others may have close collaborative links with either clinical psychology or psychiatry services. There is no doubt that the successful management of these patients requires the cooperation of a number of clinical specialties, including psychologists, nurses, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists. Some patients may be so disturbed or disabled (or both) that they may require inpatient admission to a specialized unit with access to both mental health and medical nurses, as well as to physiotherapists and occupational therapists. In the opinion of this writer, every neurology service should have access to a specialist liaison psychiatry service.46

Management Strategies for the Neurologist

It is worth noting at this stage that patients prefer the term functional rather than hysterical, when their unexplained weakness, seizures, and other symptoms are being referred to.46

The neurologist can supplement this interview by using rating scales, which provide useful baseline pretreatment information. They include the Hopkins Symptom Checklist somatization scale to measure somatic symptoms47; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to measure anxiety and depression48 (the Beck Depression and Anxiety scales are also useful); and the Illness Perception Questionnaire, which provides a rating of illness attitudes and concerns.49 There are several measures of functional impairment, including the Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Information Project50 and the Barthel index.51

Referral to Psychiatrist/Psychologist

“In our experience, it is as important to deal with the psychological as well as the physical symptoms in problems like this (such as functional weakness).”

“In our experience, it is as important to deal with the psychological as well as the physical symptoms in problems like this (such as functional weakness).”Further Management

Traditional behavioral approaches to treatment are based on the premise that the symptoms reported by the patient are interpreted as physical but are amenable to recovery. The aim of treatment is to bring about a gradual increase in function through a combination of physical and occupational therapies. The patient receives rewards and praise for improvement of function, and reinforcement is withdrawn for continuing signs of disability. Avoiding direct confrontation of psychological problems and providing “face-saving” techniques are also regarded as key components.52 More recently, the approach to patients has changed from a predominantly medical one to one in which psychological and sociocultural aspects are equally important, and the need for organized specialist rehabilitation services involving a multidisciplinary team is recognized as essential.

What Is the Evidence?

With one or two exceptions,53 there are no large, randomized, controlled studies of treatment in patients with conversion disorders. Nor is there any good evidence to support the use of one specific intervention, such as biofeedback, hypnosis, or psychotherapy. Although repeated case series have documented the effectiveness of multidisciplinary inpatient behavioral treatment, there is little controlled research. In an innovative approach, a “strategic behavioral intervention” was shown to be superior to standard behavioral treatment for chronic nonorganic motor disorders.7 In this method, patients and their families were told that full recovery constituted proof of an organic etiology, whereas failure to recover was definite proof of psychiatric etiology. This approach clearly requires special facilities and trained personnel.

A Framework for Rehabilitation

In the absence of good experimental evidence, a possible framework for future research has been developed; it is based on published evidence and described in the World Health Organization’s International Clarification of Functioning, Disability and Health,54 which is particularly useful for patients in whom there is a disability that is out of proportion to known disease and signs. The model provides opportunities for intervention and is well suited to the kind of multidisciplinary approach that is likely to be successful in these patients.

The model emphasizes that whatever the primary cause of an illness, many factors have an influence on its manifestations. It has been pointed out that patients experience a sense of control and influence over their behavior by choosing (whenever possible) between different courses of action.55,56 The notions of free will and personal responsibility remain a core belief for most democratic and legal conceptions of human nature, and they may help explain illness not produced by disease, injury, psychopathology, or psychosocial factors.

Psychological Treatments

Because patients with conversion disorders share features in common with patients with other medically unexplained syndromes, treatments that have been used in these latter disorders may have potential. Most of the evidence-based treatments in this field involve cognitive-behavioral therapy (see Kroenke and Swindle57) or interpersonal therapy. These usually have to be undertaken by trained clinical psychologists or other clinicians. However, increasing numbers of specialist nurses are being trained to deliver these treatments; therefore, they should become more widely available.

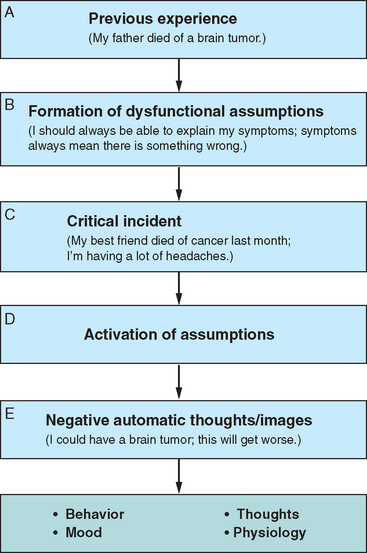

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is concerned mainly with helping the patients overcome identified problems and ascertain specified goals. It discourages “maintaining factors” such as repeated body self-checking and excessive bed rest, and challenges patients’ negative or false beliefs about symptoms. Chalder described specific cognitive-behavioral therapy–based treatment for patients with conversion disorders.58 A cognitive-behavioral approach may also help with the formulation. An example is given in Figure 20-2.

Pharmacological Treatments

There is evidence from randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews that antidepressants (both tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) can be useful in the treatment of patients with medically unexplained symptoms (such as poor sleep and pain), whether depression is present or not.59

Hallett M, Fahn S, Jancovic J, et al, editors. Psychogenic Movement Disorders: Psychobiology and Treatment of a Functional Disorder. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Halligan P, Bass C, Marshall J, editors. Contemporary Approaches to the Study of Hysteria. Clinical and Theoretical Perspectives. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Holmes EA, Brown R, Mansell W, et al. Are there two qualitatively distinct forms of dissociation? A review and some clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:1-23.

Reuber M, Elger CE. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: review and update. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:205-216.

Schrag A, Trimble M, Quinn N, et al. The syndrome of fixed dystonia: an evaluation of 103 patients. Brain. 2004;127:2360-2372.

1 Micale M. Approaching hysteria. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

2 Showalter E. Hystories. Hysterical Epidemics and Modern Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

3 Carson A, Ringbauer B, Stone J, et al. Do medically unexplained symptoms matter? A prospective cohort study of 300 new referrals to neurology outpatient clinics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:207-211.

4 Fink P, Hansen MS, Sondergaard L, et al. Mental illness in new neurological patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:817-819.

5 Rief W, Hessel A, Braehler E. Somatisation symptoms and hypochondriacal features in the general population. Psychosomat Med. 2001;63:595-602.

6 Eames P. Hysteria following brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992;55:1046-1051.

6a American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

7 Shapiro A, Teasell RW. Behavioural interventions in the rehabilitation of acute v chronic nonorganic (conversion/factitious) motor disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:140-146.

8 Halligan P, Bass C, Oakley D. Willful deception as illness behaviour. In: Halligan P, Bass C, Oakley D, editors. Malingering and Illness Deception. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003:3-28.

9 Spence S. Hysterical paralyses as disorders of action. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 1999;4:203-226.

10 Fahn S. Psychogenic movement disorders. In: Marsden CD, Fahn S, editors. Movement Disorders: 3. Oxford, UK: Butterworth Heinemann; 1995:359-372.

11 Holmes E, Brown R, Mansell W, et al. Are there two qualitatively distinct forms of dissociation? A review and some clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:1-25.

12 Brown RJ. The cognitive psychology of dissociative states. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2002;7:221-235.

13 Brown RJ. Psychological mechanisms of medically unexplained symptoms: an integrative conceptual model. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:793-812.

14 The search for a psychiatric Esperanto [Editorial]. BMJ. 1976;2:600-601.

15 Akagi H, House A. The clinical epidemiology of hysteria: vanishingly rare, or just vanishing? Psychol Med. 2002;32:191-194.

16 Stone J, Zeman A. Hysterical conversion—a view from clinical neurology. In: Halligan P, Bass C, Marshall J, editors. Contemporany Approaches to the study of Hysteria. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001:102-125.

17 Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M. Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? Lancet. 1999;354:936-939.

18 Crimlisk H, Bhatia K, Cope H, et al. Slater revisited: 6 year follow up study of patients with medically unexplained motor symptoms. BMJ. 1998;316:582-586.

19 Binzer M, Andersen P, Kullgren G. Clinical characteristics of patients with motor disability due to conversion disorder: a prospective control group study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 1997;63:83-88.

20 Stone J, Sharpe M, Binzer M. Motor conversion symptoms and pseudoseizures: a comparison of clinical characteristics. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:492-499.

21 Factor S, Podskalny R, Molho E. Psychogenic movement disorders: frequency, clinical profile and characteristics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59:406-412.

22 Reuber M, Elger C. Psychogenic non epileptic seizures: review and update. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:205-216.

23 Davison P, Sharpe M, Wade D, et al. “Wheelchair” patients with nonorganic disease: a psychological enquiry. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:93-103.

24 Ziv I, Djaldetti R, Zoldan Y, et al. Diagnosis of “nonorganic” limb paresis by a novel objective motor assessment: the quantitative Hoover’s test. J Neurol. 1998;245:797-802.

25 Stone J, Zeman A, Sharpe M. Functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:241-245.

26 Baker J, Silver J. Hysterical paraplegia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:375-382.

27 Heruti R, Reznik J, Adunski A, et al. Conversion motor paralysis disorder: analysis of 34 consecutive referrals. Spinal Cord. 2002;430:335-340.

28 Allanson J, Wade D, Bass C. Characteristics of patients with persistent severe disability and medically unexplained neurological symptoms: a pilot study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:307-309.

29 Hallett M, Fahn S, Jankovic J, et al, editors. Psychogenic Movement Disorders: Psychobiology and Treatment of a Functional Disorder. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

30 Fahn S, Williams D. Psychogenic dystonia. Adv Neurol. 1988;50:431-455.

31 Lang AE. Psychogenic dystonia: a review of 18 cases. Can J Neurol Sci. 1995;22:136-143.

32 Schrag A, Trimble M, Quinn N, et al. The syndrome of fixed dystonia: an evaluation of 103 patients. Brain. 2004;127:2360-2372.

33 Smith D, Defalla B, Chadwick D. The misdiagnosis of epilepsy and the management of refractory epilepsy in a specialist clinic. Q J Med. 1999;92:15-23.

34 Reuber M, Pukrop R, Bauer J, et al. Outcome in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: 1 to 10 year follow up in 164 patients. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:305-311.

35 Gould R, Miller B, Goldberg M, et al. The validity of hysterical signs and symptoms. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1986;174:593-597.

36 Rolak L. Psychogenic sensory loss. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988;176:686-687.

37 Blau N, Wiles M, Solomon F. Unilateral somatic symptoms due to hyperventilation. BMJ. 1983;286:1108.

38 O’Sullivan G, Harvey I, Bass C, et al. Psychophysiological investigations of patients with unilateral symptoms in the hyperventilation syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:664-667.

39 Fleminger J, McClure G, Dalton R. Lateral response to suggestion in relation to handedness and the side of psychogenic symptoms. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;136:562-566.

40 Toth C. Hemisensory syndrome is associated with a low diagnostic yield and a nearly uniform benign prognosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1113-1116.

41 Kathol R, Cox T, Corbett J, et al. Functional visual loss: I. A true psychiatric disorder? Psychol Med. 1983;13:307-314.

42 Ron M. The prognosis of hysteria/somatisation disorder. In: Halligan P, Bass C, Marshall J, editors. Contemporary Approaches to the Study of Hysteria. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001:271-283.

43 Crimlisk H, Bhatia K, Cope H, et al. Patterns of referral in patients with medically unexplained motor symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:217-219.

44 Stone J, Sharpe M, Rothwell P, et al. The 12-year prognosis of unilateral functional weakness and sensory disturbance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:591-596.

45 Gotz M, House A. Prognosis of symptoms that are medically unexplained. BMJ. 1998;317:536.

46 Stone J, Wojcik W, Durrance D, et al. What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? The “number needed to offend.”. BMJ. 2002;325:1449-1450.

47 Derogatis L, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13:595-605.

48 Zigmond A, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

49 Weinman J, Petrie K, Moss-Morris R, et al. The Illness Perception Questionnaire: a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of illness. Psychol Health. 1996;11:431-445.

50 Jenkinson C, Mayou R, Day A, et al. Evaluation of the Dartmouth COOP charts in a large-scale community survey in the United Kingdom. J Public Health Med. 2002;24:106-111.

51 Wade D, Collin C. The Barthel ADL Index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Disabil Stud. 1988;10:64-67.

52 Teasell R, Shapiro A. Rehabilitation of chronic motor conversion disorder. Crit Rev Phys Rehabil Med. 1993;5:1-13.

53 Moene F, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin K, et al. A randomised controlled clinical trial on the additional effect of hypnosis in a comprehensive treatment programme for inpatients with conversion disorder of the motor type. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71:66-76.

54 World Health Organization. International Clarification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Available at: http://www3.who.int/icficftemplate.cfm.

55 Wade D, Halligan P. New wine in old bottles: the WHO ICF as an explanatory model of human behaviour. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17:349-354.

56 Wade D. Medically unexplained disability—a misnomer, and an opportunity for rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15:343-347.

57 Kroenke K, Swindle R. Cognitive behavioural therapy for somatisation and symptom syndromes: a critical review of controlled clinical trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69:205-215.

58 Chalder T. Cognitive behavioural therapy as a a treatment for conversion disorders. In: Halligan P, Bass C, Marshall J, editors. Contemporary Approaches to the Study of Hysteria: Clinical and Theoretical Perspectives. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001:298-311.

59 O’Malley P, Jackson J, Santoro J, et al. Antidepressant therapy for unexplained symptoms and symptom syndromes. Fam Pract. 1999;48:980-990.

60 Binzer M, Kullgren G. Motor conversion disorder. A prospective 2- to 5-year follow-up study. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:519-527.

61 Feinstein A, Stergiopoulos V, Fine J, et al. Psychiatric outcome in patients with a psychogenic movement disorder: a prospective study. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2001;14:169-176.