Chapter 38 Control of Breathing and Acute Respiratory Failure

Normal Regulation of Breathing

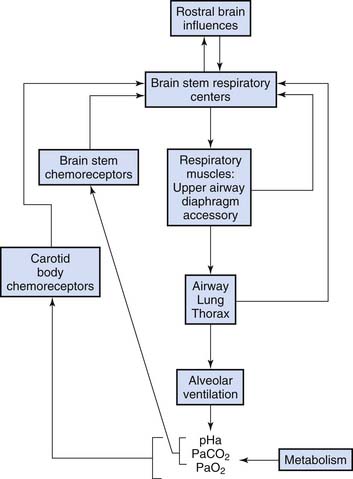

Rhythmic discharges whose timing corresponds to inspiratory and expiratory phases are generated in motor neurons of the medulla oblongata.1 During comfortable unstimulated breathing, inspiratory motor activity includes diaphragm flattening as well as a mild increase in pharyngeal muscle tone and vocal cord abduction that keep the upper airway patent during inspiratory airflow. When inspiratory muscles relax, resting expiration is passive, driven by elastic recoil of the lung and chest wall. The respiratory rate and motor intensity are modified by a variety of neural, chemical, and mechanical stimuli (Figure 38-1). With high-intensity stimulation, accessory muscles are activated, including intercostals and neck muscles. Nasal flaring occurs. Stimulated breathing also may include end-inspiratory vocal cord closure that acts to prolong lung inflation with little energy expenditure, clinically evident as grunting when the vocal cords open at the beginning of expiration. In highly stimulated breathing, abdominal muscles contract to force expiratory airflow.

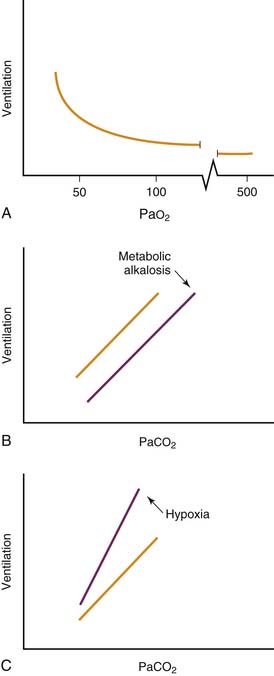

Hypoxemia is a powerful stimulus to ventilation mediated by sensory input originating in the carotid body chemoreceptor. Peripheral chemoreceptor activity and ventilation increase slightly as Pao2 falls below 500 mm Hg. Ventilation rises steeply as Pao2 falls below 50 mm Hg (Figure 38-2, A). Low oxygen tension, rather than low oxygen, content is the ventilatory stimulus. Little carotid body response results from profound anemia. Hydrogen ion concentration and carbon dioxide tension independently activate chemoreceptors in the carotid body and in the brainstem (Figure 38-2, B). The simultaneous presence of hypoxia augments the hypercapnic ventilatory response (Figure 38-2, C).

Sleep modifies breathing, and compensation for respiratory illness is most likely to fail during sleep.2 In some persons ventilatory responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia diminish during sleep. Sleep-induced reduction in upper airway tone and cough reflexes worsens the risk of obstruction and aspiration. In infants, whose thorax is compliant, awake lung volume is maintained by thoracic muscle tone and breathing at sufficiently high frequencies that expiration seldom reaches the passive resting lung volume. During sleep, inspiratory muscle tone diminishes and respiratory rate decreases, with resulting reduction in infants’ expiratory lung volume. Infants’ compensation for mechanical loads is compromised during the rapid eye movement stage of sleep more than during quiet sleep. Although sleep is a period of high risk for the sick infant, depriving the patient of sleep is counterproductive. Obstructive and central apnea are worsened by sleep deprivation in healthy infants.3

Genetic factors may account for some variation in respiratory regulation in a normal population,4 but the clinical importance of this variation in predisposing individuals to acute respiratory failure is not clear. Although apnea is common in the premature infant, immaturity of respiratory controls does not otherwise appear to be a risk factor for respiratory failure in infant populations.

Failure of Respiratory Controls

Acute Disorders of Respiratory Controls

Patients with a critical illness or injury generally hyperventilate. At least some of the increased respiratory drive can be attributed to a higher metabolic rate. Pain, discomfort, and fear also stimulate ventilation. When a stressed patient fails to hyperventilate, depressed respiratory controls and impending respiratory failure should be suspected.

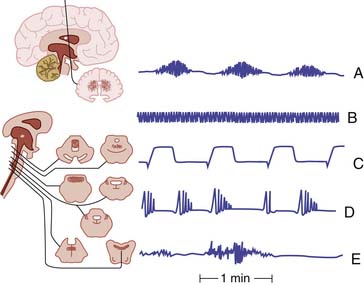

Moderate brain injuries typically are associated with hyperventilation (Figure 38-3, B), whether the injury is traumatic, infectious, or hypoxic-ischemic. The hypermetabolic state, lung pathology, and loss of inhibitory cortical influences probably combine to augment ventilation. Even when the brain-injured patient does hyperventilate, airway protective reflexes usually are impaired, seizures may ensue, and subtle progression of the brain lesion may lead to hypoventilation (Figure 38-3, A, CtoE). Resulting hypoxia may exacerbate the brain injury.

Respiratory depression by analgesic drugs, sedative agents, anticonvulsant medications, and anesthetic drugs is common. Opiates, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and propofol all have respiratory-depressing effects. Relative effects on upper airway patency and hypoxic, hypercapnic, and loading responses may be dissociated. For example, Chloral hydrate has little effect on chemosensitivity but reduces genioglossus muscle tone and predisposes to obstructive apnea. Concern regarding respiratory depression does not warrant withholding analgesia. Rather, monitoring should be appropriate. In fact, episodic hypoxia during treatment procedures may be reduced when appropriate analgesia is provided.5 Sedative agents and analgesic drugs that are rapidly cleared after a single dose may have a more prolonged duration of action when given repeatedly or continuously. Clearance rates for medications may vary with systemic disease, immaturity, or genetic factors. Sedation and analgesic-induced respiratory depression may prolong the need for mechanical ventilation. Substituting an agent that clears rapidly (such as remifentanil) for longer acting agents several hours before a planned extubation may facilitate weaning from mechanical ventilation. Dexmedetomidine, an α2 adrenergic agonist, may provide sedation with less respiratory depression than other agents.

Other medications may depress breathing without alteration of consciousness. For example, prostaglandin E1, which is given to maintain patency of the ductus arteriosus in infants with congenital heart disease, is frequently associated with respiratory depression.6

As the severely dyspneic patient decompensates, exhausted efforts may rapidly give way to periodic breathing and apnea. While this phenomenon is commonly observed in infants with lower respiratory infections7 and pertussis,8 observations in adults with near-fatal asthma reveal a similar tendency for respiratory arrest to precede cardiovascular collapse.9 The mechanism of this preterminal respiratory depression is not well understood, but it appears to occur in some patients prior to the development of hypoxia and hypercapnia.

Acute Life-Threatening Events

Patients may be admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for observation after an apparent life-threatening event (ALTE) in which caregivers perceived the need to stimulate an infant during a sudden episode of irregular breathing or apnea, cyanosis, pallor, altered level of consciousness, or hypotonia. When the history or physical examination suggests a specific cause, diagnostic confirmation is warranted. Confirmatory studies may include a blood cell count and chemistries; screening for respiratory, bloodstream, urinary, or central nervous system infection; metabolic screening; screening for gastroesophageal reflux; a chest radiograph; brain neuroimaging; a skeletal survey; an electroencephalogram; or an echocardiogram. Studies that sometimes reveal the cause when history and physical examination are nonspecific include screening for urinary infection, brain neuroimaging, screening for gastroesophageal reflux, a chest radiograph, and a white blood cell count. In one series of patients with ALTE, 33% had infections, 28% had gastrointestinal problems, 13% had neurological disorders, 3% had airway causes, 3% had other congenital problems, 4% had other noncongenital problems, and for 16%, the cause was unknown.10 See Box 38-1 for causes of apnea requiring specific therapy. In one sample, infants with ALTE who were more likely to have another subsequent severe event tended to be younger than 43 weeks’ postconceptional age, premature, and had an upper respiratory infection.11 The epidemiological characteristics of infants with ALTE differ from those who experience Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). ALTE and SIDS should be regarded as distinct entities.12 The causes and strategies to prevent SIDS continue to be an active area of investigation.

Chronic Disorders of Respiratory Controls

Structural Brain Disorders

Recognition of structural brain lesions as the cause of impaired respiratory regulation is important because some of the lesions are correctable. Congenital structural neurologic malformations may manifest as apnea or profound hypoventilation at birth or may be recognized later if respiratory impairment is mild. In particular, patients with Arnold-Chiari malformation often have central and obstructive sleep apnea. Surgical decompression may be associated with improvement13 even when performed in adults.14 Acquired lesions such as posterior fossa tumors may interfere with respiratory regulation before or after15 surgical resection.

Nonstructural Congenital Disorders

Some genetic conditions are associated with derangements in regulation of breathing. Children with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome16 have characteristic mutations in the PHOX2B gene. These patients may first come to medical attention because of growth failure, neurodevelopmental disabilities, or cor pulmonale. Abnormalities include autonomic dysfunction and cardiovascular instability as well as impaired controls of breathing. The syndrome may be recognized in the newborn period, later in childhood, and occasionally in adults. Sleep hypoventilation predominates in persons with congenital central hypoventilation syndrome, although some patients also experience respiratory insufficiency while awake. The disorder often is fatal without mechanical ventilation. Early mechanical ventilation may reduce the sequelae and improve long-term neurodevelopmental outcome.

Prader-Willi syndrome is a multigenic disorder initially presenting with hypotonia and then with progressive obesity, growth failure, neurodevelopmental disabilities, reduced ventilatory response to hypoxia and hypercapnia, sleep hypoventilation, and apnea.17

Rett syndrome is an X-linked disorder affecting development, behavior, and autonomic and respiratory regulation. Many patients with Rett syndrome have seizures. Abnormalities often are present in the MECP2 gene, although some patients with characteristic clinical features have other genetic findings.18 Multiple phenotypes exist in regard to the respiratory control disorder, with hyperventilation, hypoventilation, and apneustic breathing seen in subgroups.19

Many other genetic syndromes with severe neurological manifestations have impaired upper airway motor function, respiratory cycle timing, and respiratory effort nonspecifically associated with their brain disorder. Nongenetic congenital disorders may impair respiratory controls. For example, children with cerebral palsy occasionally have neurologic deficits of pharyngeal tone, although the central drive to breathe usually is intact.

Nonstructural Acquired Chronic Disorders

Some patients with severe chronic respiratory disease have blunted ventilatory responses to hypoxia, hypercapnia, or respiratory mechanical loads. A concern regarding supplemental oxygen is sometimes raised in the care of patients with acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory disease. It is sometimes argued that administration of supplemental oxygen causes respiratory failure in patients with chronic CO2 insensitivity who might depend on hypoxic drive to breathe. Of greater concern are the adverse effects of hypoxia. Because the hypoxic drive to breathe only increases substantially at oxygen tension below 50 mm Hg (see Figure 38-2, A), it is virtually impossible to maintain stable respiratory stimulation with mild and “safe” hypoxia without risking episodic life-threatening hypoxia. If a patient is so poorly compensated that removal of hypoxic drive results in hypoventilation, then mechanical ventilation may be the safest management strategy, unless end-of-life plans specifically exclude mechanical ventilation.

Obesity causes hypoventilation by a complex interaction of factors including mechanical loads on the respiratory system, reduction of lung volume, upper airway obstruction, and impaired respiratory regulation.20 In obese patients, weight loss often improves hypoventilation.

Apparently healthy preterm infants may have postanesthetic apnea until the age of 60 weeks’ postconceptional age.21,22 Apneic events occurred within 2 hours of surgery in 72% of patients, but in the remainder, respiratory irregularity began as late as 12 hours postoperatively. Both obstructive and central mechanisms of apnea were observed. Continuous monitoring for at least 12 hours after anesthesia is warranted when surgery is required for infants born prematurely who are still younger than 60 weeks’ postconceptional age.

Sleep hypoventilation tends to occur in adults with hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus.23 Little information is available regarding the pediatric patient or the specific role of the endocrine disorder versus obesity.

Recognition and Treatment

The Deteriorating Patient

Evaluation of patients during respiratory decompensation often is limited by their rapidly evolving state. Given the safety and effectiveness of endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, support should be initiated promptly when there is substantial suspicion concerning impaired regulation of breathing in the critically ill patient. Apnea may suggest the presence of a systemic disorder requiring specific treatment (Box 38-1).

Evaluation During Recovery

Finally, some patients fail to increase effort despite hypercapnia and hypoxia during the trial of spontaneous breathing. Others lack a gag response. In these cases, obvious deficiency of neural controls of breathing contributes to persistence of their respiratory insufficiency.

Measuring Respiratory Drive

However, useful and clinically feasible measurements of respiratory drive are possible. Whatever the baseline ventilation, an increase in ventilation in response to hypercapnia is evidence of at least partially intact chemosensitivity.24,25 The pressure generated at the airway in the first 0.1 seconds of inspiration against an occluded airway (P0.1) parallels experimental direct measures of respiratory center output. Increase in P0.1 with hypercapnia indicates at least partially intact chemosensitivity. In one study, augmented P0.1 response to hypercapnia was associated with more successful extubation in a group of patients with brainstem tumors who were at risk for depressed respiratory controls.26 These techniques are feasible for application in the pediatric critical care population, but published data are not available.

1. Smith J.C., Ellenberger H.H., Ballanyi K., et al. Pre-Botzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science. 1991;254:726.

2. Casey K.R., Cantillo K.O., Brown L.K. Sleep-related hypoventilation/hypoxemic syndromes. Chest. 2007;131:1936-1948.

3. Canet E., Gaultier C., D’Allest A.M., et al. Effects of sleep deprivation on respiratory events during sleep in healthy infants. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:1158.

4. Weil J.V. Variation in human ventilatory control-genetic influence on the hypoxic ventilatory response. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;135:239-246.

5. Pokela M.L. Pain relief can reduce hypoxemia in distressed neonates during routine treatment procedures. Pediatrics. 1994;93:379.

6. Meckler G.D., Lowe C. To intubate or not to intubate? Transporting infants on prostaglandin E1. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e25-30.

7. Ralston S., Hill V. Incidence of apnea in infants hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2009;155:728-733.

8. Surridge J., Segedin E.R., Grant C.C. Pertussis requiring intensive care. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:970-975.

9. Molfino N.A., Nannini L.J., Martelli A.N., et al. Respiratory arrest in near-fatal asthma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:285.

10. Brand D.A., Altman R.L., Purtill K., et al. Yield of diagnostic testing in infants who have had an apparent life-threatening event. Pediatrics. 2005;115:885-893.

11. Al-Kindy H.A., Gelinas J.F., Hatzakis G., et al. Risk factors for extreme events in infants hospitalized for apparent life threatening events. J Pediatr. 2009;154:332-337.

12. Esani N., Hodgman J.E., Ehsani N., et al. Apparent life-threatening events and sudden infant death syndrome: comparison of risk factors. J Pediatr. 2008;152:365-370.

13. Pollack I.F., Kinnunen D., Albright A.L. The effect of early craniocervical decompression on functional outcome in neonates and young infants with myelodysplasia and symptomatic Chiari II malformation. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:703.

14. Botelho R.V., Bittencourt L.R., Rotta J.M., et al. The effects of posterior fossa decompressive surgery in adult patients with Chiari malformation and sleep apnea. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:800-807.

15. Chen M.L., Witmans M.B., Tablizo M.A., et al. Disordered respiratory control in children with partial cerebellar resections. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;40:88-91.

16. Weese-Mayer D.E., Rand C.M., Berry-Kravis E.M., et al. Congenital central hypoventilation syndrome from past to future. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:521-535.

17. Zanella S., Tauber M., Muscatelli F. Breathing deficits of the Prader-Willi syndrome. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;168:119-124.

18. Raizis A.M., Saleem M., MacKay R., et al. Spectrum of MECP2 mutations in New Zealand Rett syndrome patients. N Z Med J. 2009;122:21-28.

19. Julu P.O.O., Engerstrom I.W., Hansaen S., et al. Cardiorespiratory challenges in Rett’s syndrome. Lancet. 2008;371:1981-1983.

20. Piper A.J., Grundstein R.R. Big breathing—the complex interaction of obesity, hypoventilation, weight loss and respiratory function. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:199-205.

21. Kurth C.D., Spitzer A.R., Broennle A.M., et al. Postoperative apnea in preterm infants. Anesthesiology. 1987;66:483.

22. Kurth C.D., LeBard S.E. Association of postoperative apnea, airway obstruction, and hypoxia in former premature infants. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:22.

23. Bottini P., Tantucci C. Sleep apnea in endocrine diseases. Respiration. 2003;70:320-327.

24. Raurich J.M., Rialp G., Ibanez J., et al. Hypercapnia test as a predictor of success in spontaneous breathing trials and extubation. Respir Care. 2008;53:1012-1018.

25. Nickol A.H., Dunroy H., Polkey M.I., et al. A quick and easy method of measuring the hypercapnic ventilatory response in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2009;103:258-267.

26. Wu Y.K., Lee C.H., Shia B.C., et al. Response to hypercapnic challenge is associated with successful weaning form prolonged ventilation due to brainstem lesions. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:108-114.