2 Continuous Peripheral Nerve Blocks

General Approaches to Continuous Catheter Placement

Technique Details

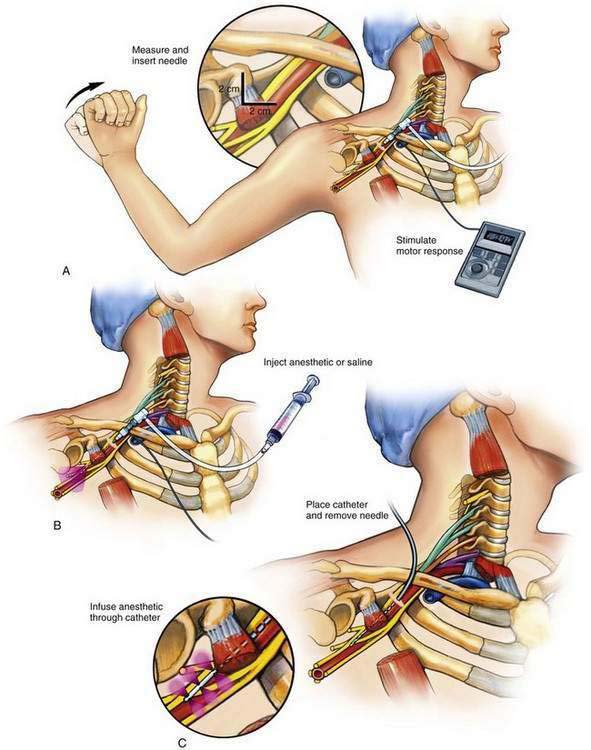

Nonstimulating Catheter Technique

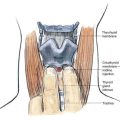

An insulated stimulating needle is directed near the peripheral nerve to be blocked with a stimulator current output of 1.5 mA, or under ultrasonographic guidance. The final needle position is confirmed by (1) observing an appropriate motor response with the nerve stimulator current output set at 0.3 to 0.5 mA, with a frequency of 1 to 2 Hz and a pulse width of 100 to 300 µsec; or (2) demonstrating the needle to be near the nerve by ultrasonography. When ultrasonography is used, it is customary to inject a small volume of fluid through the needle to demonstrate its spread around the nerve—so-called hydrodissection and doughnut sign formation. The needle is often attached to a syringe by tubing from a side port (Fig. 2-1). This arrangement allows the physician to aspirate for blood or cerebrospinal fluid during needle placement and thus minimize unintentional intravascular or intrathecal injection; however, this can give potentially dangerous false-negative results because the suction produced by needle aspiration causes the surrounding tissue to obstruct the needle tip, thus allowing injection of local anesthetic into the intravascular or intrathecal space. Ultrasonography theoretically protects against missing the obstruction, although this depends on the operator’s skill.

A variety of local anesthetic solutions are used for the block. Many prefer ropivacaine, but this choice depends on the clinical situation. More often than not during this method a bolus (20 to 40 mL) of the local anesthetic is injected through the needle before catheter insertion and provides the primary block. This is then followed by catheter placement and an infusion of local anesthetic solution through the catheter, producing what many call the secondary block (see Fig. 2-1C).

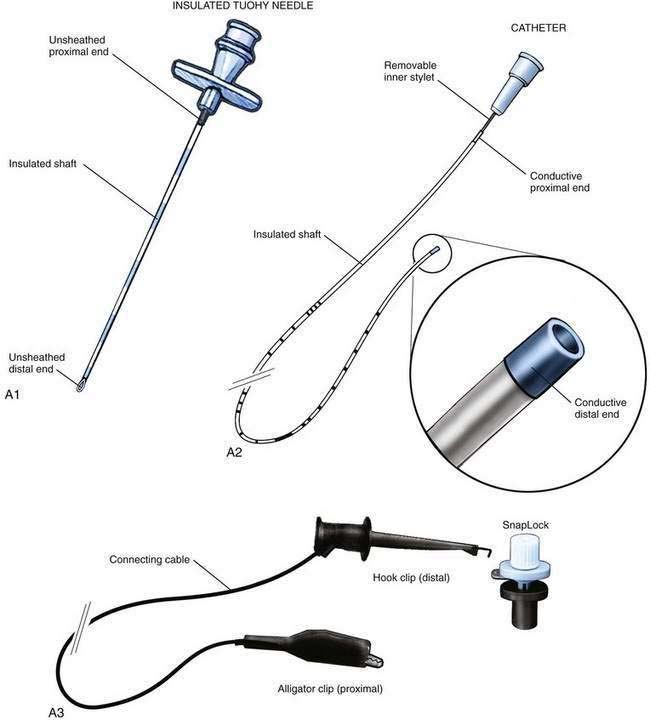

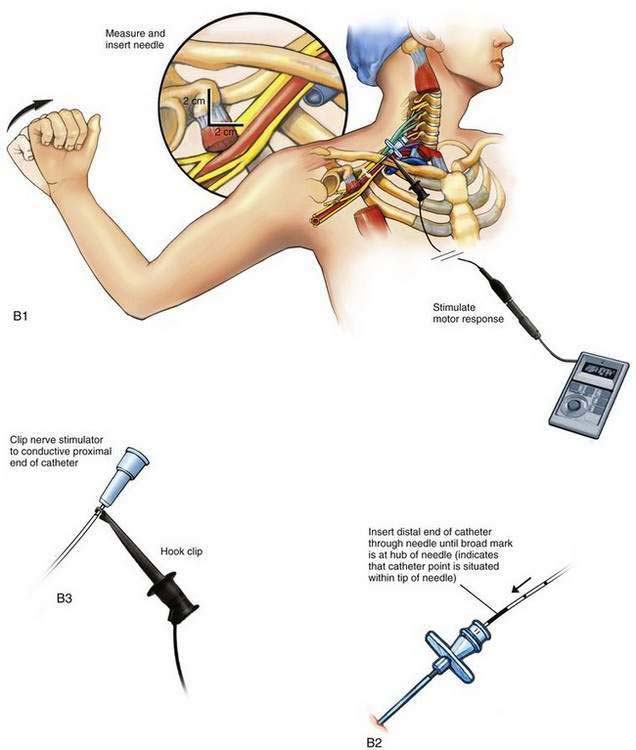

Stimulating Catheter Technique

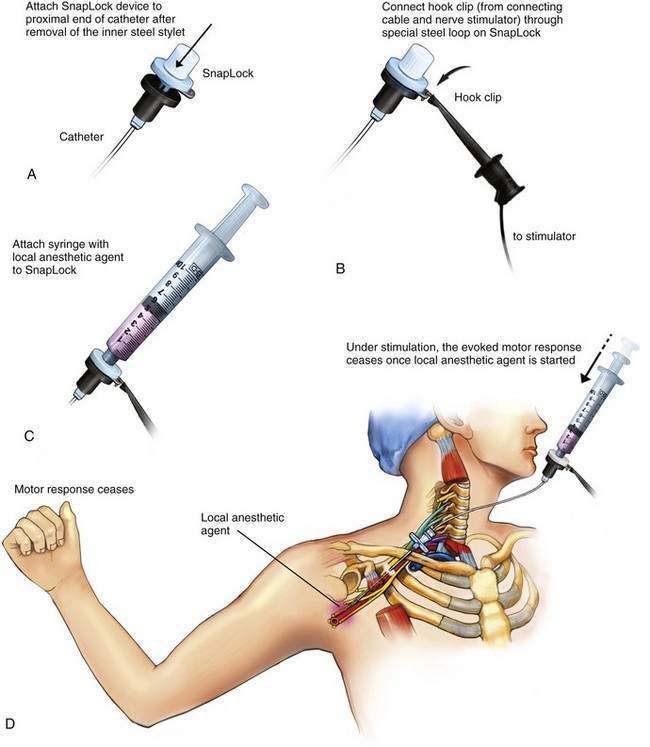

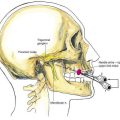

The insulated stimulating needle (Fig. 2-2A) is directed to the peripheral nerve to be blocked as in the nonstimulating technique approach described earlier, using either a nerve stimulator current output of 1.5 mA or ultrasonographic guidance. Adequate needle position is confirmed by observing an appropriate motor response with either (1) the nerve stimulator current output set at 0.3 to 0.5 mA, with a frequency of 1 to 2 Hz and a pulse width of 100 to 300 µsec or (2) the “doughnut sign” seen after hydrodissection when ultrasonography is used. Only 5% dextrose in water should be used for hydrodissection; saline or local anesthetic impairs the electrical stimulation of the nerve and makes catheter placement with this technique difficult.

The needle is held steady in the desired position and, usually without injecting any solution through the needle, the negative lead off the nerve stimulator is clipped to the proximal end of the stimulating catheter, which is in turn advanced through the needle (Fig. 2-2B). The desired motor response with catheter advancement through the distal end of the needle should be similar to that elicited during initial needle placement. If the motor response decreases or disappears, it usually indicates that the catheter is being directed away from the nerve with advancement. Using this paired needle and catheter assembly, the catheter can be withdrawn back into the needle without undue concern over catheter shearing. If refinement in catheter positioning is required, the distal catheter is withdrawn into the shaft of the needle. Then, a small positioning change is made to the needle, typically by rotating it clockwise or counterclockwise or by advancing or withdrawing the needle a few millimeters, and then the catheter is advanced again, similar to the earlier catheter positioning steps. This process may be repeated until the desired motor response is elicited during catheter advancement. The desired motor response should continue as the catheter is advanced 3 to 5 cm along the neural structures.

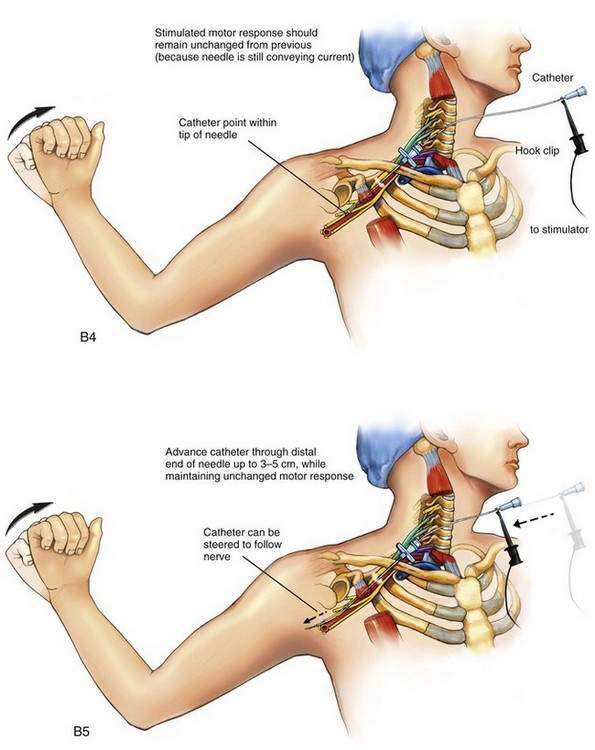

Fixation of the Catheter

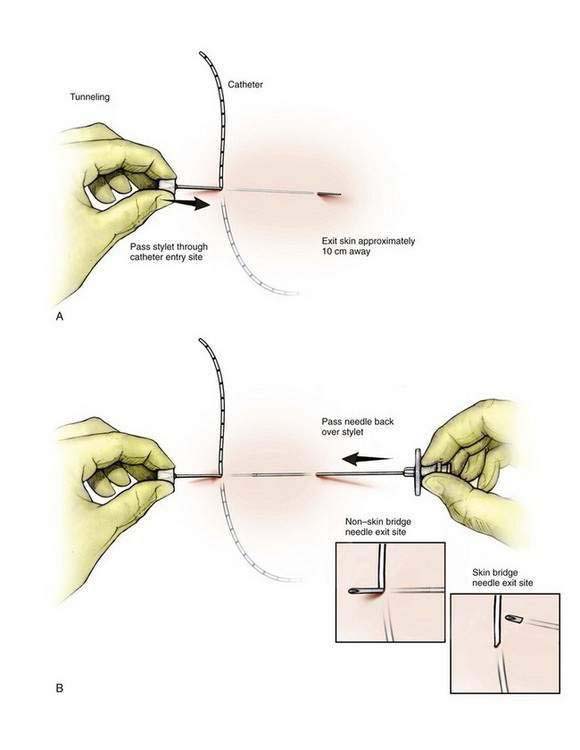

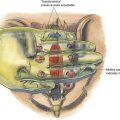

For a skin bridge technique, the stylet of the Tuohy needle (Fig. 2-3A) is used as the needle guide and directed to enter the skin 2 to 3 cm from the catheter exit site. If a non–skin bridge technique is chosen, the stylet is placed through the skin at the catheter exit site. In each technique the stylet is advanced to the desired skin exit site subcutaneously over a distance of approximately 10 cm, or the length of the stylet. The Tuohy needle is then advanced in a retrograde fashion over the stylet (Fig. 2-3B). Next, the stylet is removed and the catheter is advanced through the needle (Fig. 2-3C) until it is secure and the needle can be withdrawn, leaving the catheter tunneled. If a skin bridge technique is used, a short length of plastic tubing is inserted to protect the skin under the skin bridge (Fig. 2-3D).

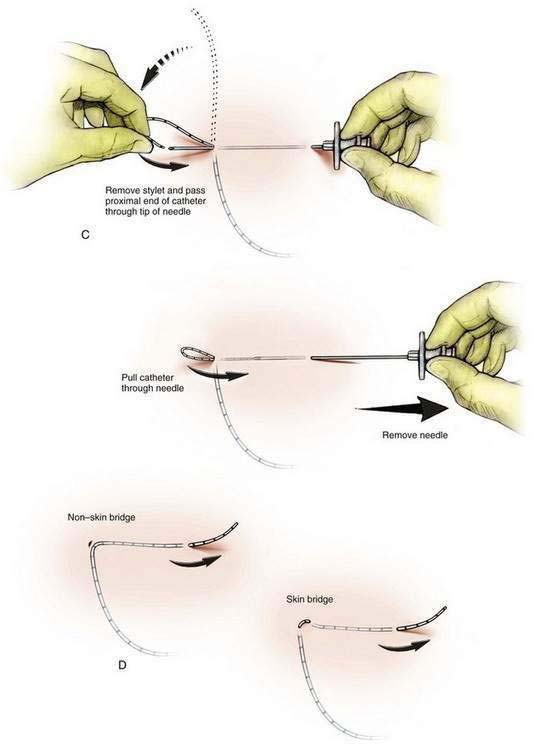

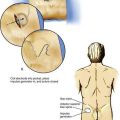

After the catheter tunneling has been completed, the catheter should be checked for stable distal catheter tip position. For this purpose, a device such as the SnapLock (Arrow International, Reading, Penn), which allows continuous nerve stimulation through the catheter, is attached to the catheter. The syringe containing the local anesthetic is attached to the SnapLock (Fig. 2-4) and then, while stimulation of the catheter continues to elicit a motor response, the injection of local anesthetic is started. The evoked motor response should cease immediately on injection due to the dispersion of the current by the conductive fluid. Saline injected through the catheter will result in the same discontinuation of motor response, but plain sterile water will not. More current will therefore be required to produce a motor response.