CHAPTER 70 Constrictive Pericarditis

PREVALENCE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Constrictive pericarditis is uncommon. It is more commonly seen in patients with a preexisting episode of pericarditis, prior surgery, or prior radiation therapy, although many patients have no documented antecedent pericardial disease. In a prospective assessment of the outcome of acute pericarditis, 56% of patients with tuberculous pericarditis, 35% of patients with purulent pericarditis, and 17% of patients with neoplastic pericardial disease developed constrictive pericarditis.1 Only 1% of patients with idiopathic pericarditis developed constrictive pericarditis in this series. In contrast, transient constrictive pericarditis (see later) was more commonly seen in patients with idiopathic pericarditis, occurring in approximately 20% of cases.2

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

In the United States, the most common causes of constrictive pericarditis are idiopathic or postviral pericarditis, prior cardiac surgery, and radiation therapy (Table 70-1). The scarred pericardium inhibits the ability of the cardiac chambers to dilate during diastolic filling, acting as a cage covering the heart. As a result of the inability to dilate, the intracardiac pressures of each chamber are elevated and equalized. This elevated pressure is transmitted to the pulmonary and systemic veins. Because the atrial pressures are elevated, there is rapid filling of the ventricles early in ventricular diastole. This ventricular filling rapidly ceases when the ventricle can no longer expand to accept the incoming volume. Systemic venous hypertension results in hepatomegaly, ascites, and peripheral edema.

Data from Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43:1445-1452.

MANIFESTATIONS OF DISEASE

Clinical Presentation

Patients with constrictive pericarditis present with signs and symptoms of right heart failure. Patients may complain of dyspnea, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, abdominal fullness secondary to ascites, and pedal edema. On physical examination, there is distention of the neck veins, peripheral edema, and hepatomegaly. In a patient without pericardial constriction, there is a decrease in jugular venous pressure during inspiration because of decrease in intrathoracic pressure. In patients with constrictive pericarditis, because the intrapericardial pressure is dissociated from the intrathoracic pressure, there is an increase in jugular venous pressure during inspiration (Kussmaul sign).3 A pericardial knock, which corresponds to the rapid cessation of ventricular filling, can be heard along the cardiac apex and left sternal border.

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Ultrasonography

The classic finding of constrictive pericarditis is the equalization of the end-diastolic pressure in all four cardiac chambers with early rapid diastolic filling. Paradoxical motion of the interventricular septum may also be seen. Pericardial thickening may be missed on transthoracic echocardiography, particularly if it is located in the near field, or if there is localized involvement.4,5 Transesophageal echocardiography has been found to be more sensitive in detecting pericardial thickening compared with transthoracic echocardiography.6 Dilation of the atria, inferior vena cava, and hepatic veins may be noted.

Computed Tomography

CT is able to document the presence of pericardial thickening or calcification or both. The pericardium normally measures 2 mm or less, and can be reliably identified only when surrounded by mediastinal and subepicardial fat. Pericardial thickening may involve most of the pericardial surface or may be localized, either unilateral or affecting the atrioventricular groove preferentially. The effect of the pericardial thickening on the cardiac chambers and mediastinal structures can also be assessed by CT. Global or unilateral pericardial thickening in the setting of constrictive pericarditis causes a tubelike narrowing of the ventricles (Fig. 70-1). If there is involvement of the pericardium covering the atrioventricular groove, waistlike narrowing can be seen. The atria and superior and inferior venae cavae may be enlarged reflecting the increased pressure limiting inflow of blood into the ventricles. The interventricular septum is often straightened or sinusoidal in appearance. Pleural effusions and ascites are frequently identified as well.

A subset of patients with constrictive physiology may have no detectable pericardial thickening yet would benefit from pericardiectomy.7,8 In a series of 26 patients who underwent pericardiectomy despite the absence of pericardial thickening or calcification, on pathologic examination, all showed areas of either focal fibrosis or calcification.7 In these patients without demonstrable pericardial thickening, the constrictive physiology is thought to be the result of pericardial adhesions.5 If ECG gated images are obtained, abnormal septal motion can be evaluated. The myocardium can also be assessed for myocardial thinning because this finding has been associated with increased mortality after pericardiectomy.9

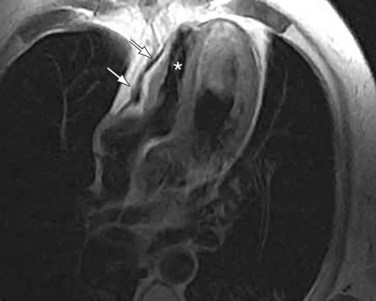

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Although it cannot differentiate between calcified and thickened pericardium, MRI can be used to detect pericardial thickening and the associated cardiac deformities typically seen in patients with constrictive pericarditis (Fig. 70-2). MRI is better than CT in distinguishing small pericardial effusions from pericardial thickening. In patients who have constrictive pericarditis without associated pericardial thickening, myocardial tagging techniques can be used to document the lack of normal movement between the myocardium and pericardium.10 Just as pericardial thickening can exist without constrictive pericarditis, pericardial adhesions identified with myocardial tagging can also occur in the absence of constrictive physiology. Septal motion can be evaluated using cine MRI sequences. As with echocardiography, paradoxical diastolic motion (“septal bounce”) may be present.11 The myocardium can also be assessed for myocardial thinning because this finding has been associated with increased mortality after pericardiectomy.9

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Medical

Transient constrictive pericarditis can acutely follow acute pericarditis. In these cases, constrictive physiology is present on echocardiography and persists after pericardiocentesis. This constrictive physiology occurs in a relative subacute phase and differs from chronic cases of constrictive pericarditis that tend to develop some time after the initial insult. Patients who develop signs related to constrictive pericarditis shortly after being diagnosed with acute pericarditis can receive conservative medical therapy, and their symptoms may resolve. If resolution does not occur over time, pericardiectomy can be considered.12,13

Surgical/Interventional

For chronic cases of constrictive pericarditis, radical pericardiectomy is the preferred treatment, although the mortality rate is significant. In a series of 163 patients undergoing pericardiectomy for constrictive pericarditis, the overall mortality rate was 6.1%, although mortality was 21.4% for patients in whom the constrictive pericarditis was caused by prior radiation therapy.14 In one series, there was a 100% mortality rate in patients with evidence of myocardial atrophy or fibrosis on CT or MRI who subsequently underwent pericardiectomy.9

INFORMATION FOR THE REFERRING PHYSICIAN

KEY POINTS

Constrictive pericarditis has been reported in the absence of appreciable thickening or calcification of the pericardium.

Constrictive pericarditis has been reported in the absence of appreciable thickening or calcification of the pericardium.Kim JS, Kim HH, Yoon Y. Imaging of pericardial diseases. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:626-631.

Rienmüller R, Gröll R, Lipton MJ. CT and MR imaging of pericardial disease. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:587-601.

Wang ZJ, Reddy GP, Gotway MB, et al. CT and MR imaging of pericardial disease. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:S167-S180.

1 Permanyer-Miralda G, Sagristá-Sauled J, Soler-Soler J. Primary acute pericardial disease: a prospective series of 231 consecutive patients. Am J Cardiol. 1985;56:623-630.

2 Sagristá-Sauled J. Pericardial constriction: uncommon patterns. Heart. 2004;90:257-258.

3 Talreja DR, Nishimura RA, Oh JK, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: novel criteria for diagnosis in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:315-319.

4 Otto CM. Pericardial disease: two-dimensional echocardiographic and Doppler findings. In: Otto CM, editor. Textbook of Clinical Echocardiography. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:213-228.

5 Goldstein JA. Cardiac tamponade, constrictive pericarditis, and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2004;29:503-567.

6 Ling LH, Oh JK, Tei C, et al. Pericardial thickness measured with transesophageal echocardiography: feasibility and potential clinical usefulness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1317-1323.

7 Talreja DR, Edwards WD, Danielson GK, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in 26 patients with histologically normal pericardial thickness. Circulation. 2003;108:1852-1857.

8 Oh KY, Shimzu M, Edwards WD, et al. Surgical pathology of the parietal pericardium: a study of 344 cases (1993-1999). Cardiovasc Pathol. 2001;10:157-168.

9 Rienmüller R, Gürgan M, Erdmann E, et al. CT and MR evaluation of pericardial constriction: a new diagnostic and therapeutic concept. J Thorac Imaging. 1993;8:108-121.

10 Kojima S, Yamada N, Goto Y. Diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis by tagged cine magnetic resonance imaging. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:373-374.

11 Spodick DH. Acute pericarditis: current concepts and practice. JAMA. 2003;289:1150-1153.

12 Haley JH, Tajik AJ, Danielson GK, et al. Transient constrictive pericarditis: causes and natural history. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:271-275.

13 Sagristá-Sauled J, Permanyer-Miralda G, Candell-Riera J, et al. Transient cardiac constriction: an unrecognized pattern of evolution in effusive acute idiopathic pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59:961-966.

14 Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1445-1452.

FIGURE 70-1

FIGURE 70-1

FIGURE 70-2

FIGURE 70-2