Chapter 30

Constipation (Case 23)

Christopher P. Farrell DO and Gary Newman MD

Case: A 67-year-old woman presents to the ED complaining of abdominal discomfort, decreased frequency of her bowel movements, and mild abdominal distension. She is clearly distressed in the ED, unable to find a comfortable position on the stretcher, and wincing with abdominal pain.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) |

Impaction |

|

Colon cancer |

Medication-related |

|

Volvulus |

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie syndrome) |

Speaking Intelligently

When asked to see a patient for constipation, we first want to find out the patient’s definition of constipation. Has she not been able to move her bowels in days or is it just not as frequently or as comfortable as she would like? Most cases of constipation aren’t critical; however, a bowel obstruction or volvulus requires more urgent care. If she has not been able to move her bowels or pass any gas for days, she may need more immediate treatment. A thorough history is important, concentrating on alarm symptoms such as unintentional weight loss, rectal bleeding, or a recent or sudden change in bowel habits. Any surgical history should be reviewed, along with the patient’s medications, followed by a dedicated abdominal and rectal exam.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• A sigmoid volvulus, while rare, requires an urgent endoscopic decompression with flexible sigmoidoscopy; if untreated, it can lead to colonic ischemia and irreversible damage.

• A fecal impaction can be diagnosed and treated quickly with a simple rectal exam and disimpaction.

• Most causes of constipation are not emergent.

History

• Establish the patient’s definition of constipation.

• Ask about the quality of the patient’s bowel movements and frequency.

• Is there associated bleeding or abdominal pain?

• Ask about family history of GI disorders, most importantly colon cancer.

• Perform a thorough review of the patient’s medications.

Physical Examination

• Assess vital signs and hemodynamic stability.

Tests for Consideration

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Irritable Bowel Syndrome |

|

|

Pφ |

IBS is a very common disorder characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits. The condition can affect both sexes at any age but is prominent in young females. Patients regularly experience abdominal cramping that is relieved with a bowel movement. The bowel habits can be either constipation-predominant or diarrhea-predominant in nature. Constipation-predominant patients usually experience chronic constipation with intermittent diarrhea or regular bowel movements. The pathophysiology of IBS remains unknown; however, hereditary and environmental factors probably play a role. Psychosocial dysfunction also contributes to IBS and its fluctuating symptoms. |

|

TP |

Crampy abdominal pain, incomplete evacuation of bowels, bloating, gas (flatulence or belching), hard or lumpy stools, relief of abdominal discomfort with defecation. |

|

The main diagnostic tool is the Rome III diagnostic criteria. This includes recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days a month for the last 3 months associated with two of the following: improvement with defecation, onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, or onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool. |

|

|

Tx |

Initially, constipation-predominant patients can be treated with fiber supplementation and psychosocial therapies, if emotional stress is a contributing factor. A bowel regimen in the form of a laxative, suppository, or enema may be needed if symptoms persist. Finally, specific medications that activate chloride channels or stimulate the release of serotonin can be used in refractory cases. See Cecil Essentials 34. |

|

Colon Cancer |

|

|

Pφ |

Colon cancer is a malignancy that usually arises from a long-standing polyp. The disease can be localized to the colon or can metastasize to other organs, most frequently the liver. Cancers in the proximal colon may present as iron deficiency anemia from a slow occult hemorrhage, while cancers in the distal colon can present with obstructive symptoms or with gross bleeding. |

|

TP |

Symptomatic iron deficiency anemia, gross or occult blood in the stool, change in bowel habits (obstruction, diarrhea), unintentional weight loss, abdominal pain. |

|

Dx |

CT scans can sometimes demonstrate lesions in the colon and are necessary to evaluate for metastatic disease. Colonoscopy is the best diagnostic test to assess for colon cancer, and allows for definitive biopsy samples to be taken and examination of the entire colon; flexible sigmoidoscopy permits examination of only the rectum and distal colon. |

|

Tx |

Resection of polyps can usually be achieved endoscopically. Cancer resections generally require surgery, which can be performed by open or laparoscopic techniques. Radiation therapy is now used routinely for preoperative treatment of rectal cancer. When colon cancer is metastatic, chemotherapy is the treatment of choice. See Cecil Essentials 39, 57. |

|

Pφ |

An impaction results from an accumulation of hardened stool, most frequently occurring in the rectum. This prevents the evacuation of stool, resulting in pain and constipation. This condition occurs more commonly in the elderly and those with chronic neuropathic disorders, from immobility, and in those on medications that alter colonic motility. |

|

TP |

Inability to move bowels with straining, rectal pain, and pressure. Overflow diarrhea (encopresis) may occur; rectal ulcers may develop. |

|

Dx |

A fecal impaction can usually be diagnosed very easily with just a simple digital rectal exam. If the impaction is beyond the reach of a rectal exam, an obstruction series or abdominal radiograph will often demonstrate a mass of hardened stool. A CT scan can visualize and localize an area of impaction. |

|

Tx |

Manual digital disimpaction can be performed at the bedside or under general anesthesia, if necessary. Enemas, suppositories, and laxatives can be used to help break up and resolve an impaction. Following the resolution of an impaction, the patient should be given a fiber supplement and a bowel regimen containing a stool softener and possibly a stimulant or osmotic laxative to prevent further episodes. Narcotics and other medications possibly contributing to the problem should be eliminated to avoid repeat episodes. |

|

Medication-Related Symptoms |

|

|

Pφ |

Medications are an extremely common cause of constipation. Narcotics, calcium channel blockers, and anticholinergics are frequent culprits. The chronic use of these medicines requires an adequate bowel regimen and daily fiber supplementation to avoid recurrent issues with constipation. |

|

TP |

Difficulty moving bowels, infrequent bowel movements, painful bowel movements, localized rectal bleeding from straining. |

|

Dx |

A thorough history is essential for diagnosing constipation due to medication administration. A complete review of the patient’s medication list is required. A detailed physical exam, along with appropriate radiologic testing, is essential to rule out any other etiology for the patient’s symptom of constipation. |

|

The treatment of medication-related constipation can be as simple as removing the offending agent. The patient should at least temporarily be placed on a bowel regimen in the form of a fiber supplementation, stool softener, or laxative, depending on the severity of symptoms. |

|

|

Volvulus |

|

|

Pφ |

A volvulus is a twisting of the bowel upon itself, causing an obstruction, most commonly occurring in the sigmoid colon and cecum. Alterations in anatomic features have a role in this pathology. Left untreated, this condition can progress to ischemia and necrosis due to compromised blood supply. |

|

TP |

Progressive abdominal distension and pain, nausea, inability to move bowels, and the absence of flatus. |

|

Dx |

An obstruction series or abdominal radiograph is a good initial test to evaluate for an obstruction, and a “coffee bean” or “bird’s beak” sign can be seen with a sigmoid volvulus. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis helps distinguish findings such as a volvulus and isolates the exact area of concern. A barium enema can also diagnose this condition but is used less often and is not as immediate or easily available. |

|

Tx |

If a patient presents with a sigmoid volvulus, an emergent endoscopic decompression should be performed, if possible, with a flexible sigmoidoscopy. Occasionally, a decompressive tube is left in place beyond the area of previous torsion. Following decompression, most patients need a sigmoidectomy to prevent a recurrent volvulus. See Cecil Essentials 35. |

|

Acute Colonic Pseudo-obstruction (Ogilvie Syndrome) |

|

|

Pφ |

Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, also known as Ogilvie syndrome, presents as gross dilatation of the cecum and right hemicolon in the absence of an anatomic lesion causing an obstruction that can present as constipation. Trauma, neurologic conditions, surgery (abdominal/obstetric, cardiovascular, orthopedic), severe medical illness, metabolic imbalance (hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia), malignancy, and medications (narcotics, calcium channel blockers) all can predispose patients to this condition. Ogilvie’s is more commonly found in men over 60 years of age and is thought to be due to impairment in the autonomic nervous system. |

|

Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation and/or diarrhea, and significant abdominal distension. |

|

|

Dx |

On physical exam, the abdomen is distended and tympanitic, usually with bowel sounds present. An obstruction series or abdominal radiograph shows a dilated colon, more commonly from the cecum to the splenic flexure. This finding is also seen on a CT scan or barium enema, without evidence of distal obstruction. |

|

Tx |

Initial treatment involves supportive care with the correction of metabolic imbalances and the removal of precipitating factors, such as medications. An NG tube and/or rectal tube can be inserted for further symptomatic relief. Gentle enemas and stimulating suppositories can be utilized to help induce colonic motility. More aggressive pharmacologic therapy can be given with neostigmine or erythromycin; however, their efficacy is questionable, and each possesses its own side effects. Finally, endoscopic decompression is sometimes warranted if symptoms are severe or colonic dilation increases (11–13 cm). A decompressive tube can be left in the transverse colon to allow for continued treatment. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup.

Authors

Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al.

Institution

Gastroenterology and Nutrition Service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York

Reference

N Engl J Med 1993;329:1977–1981

Problem

This study was performed to evaluate the utility of removing adenomatous polyps from the colon and rectum as a form of colorectal cancer prevention.

Intervention

Patients who underwent colonoscopies with removal of adenomatous polyps were followed with periodic surveillance colonoscopies to examine for any evidence of colorectal cancer.

Comparison/control (quality of evidence)

The incidence rate of colorectal cancer was compared with that in three reference groups—two cohorts in which polyps were not removed and one general-population registry, after adjustment for sex, age, and polyp size.

Outcome/effect

Removal of adenomatous polyps with colonoscopic polypectomies resulted in a lower than expected incidence of colorectal cancer.

Historical significance/comments

The findings from this study support the hypothesis that colorectal adenomatous polyps progress to adenocarcinoma and should be screened for and removed with colonoscopies.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Teaching Visual: Physician and Patient Perspectives on Procedural Preparation

Melissa Morgan DO, Michael D. Share MD, Deena Roemer, Edward Share MD

When I obtain consent from a patient for colonoscopy, I review the following issues:

She will lie on her left side and be given sedation.

She will lie on her left side and be given sedation.

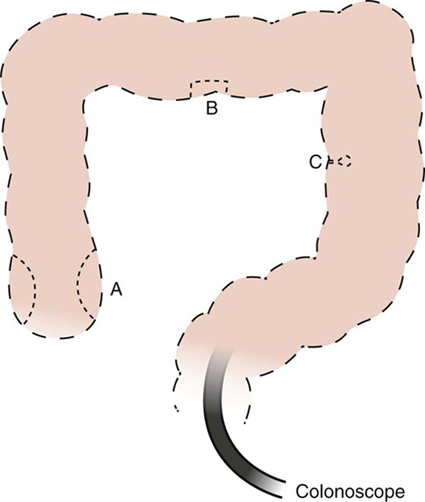

The colonoscope is then inserted into the rectum. I emphasize that it is a small, flexible tube with a light and a camera on the end; using my diagram (Fig. 30-1), I emphasize that it will be advanced all the way to the beginning of the colon.

The colonoscope is then inserted into the rectum. I emphasize that it is a small, flexible tube with a light and a camera on the end; using my diagram (Fig. 30-1), I emphasize that it will be advanced all the way to the beginning of the colon.

Connect the large dashes to draw a colon for your patient.

Connect the large dashes to draw a colon for your patient.

Demonstrate how the colonoscope will navigate to the cecum.

Demonstrate how the colonoscope will navigate to the cecum.

If any abnormalities are seen, biopsy samples can be obtained with small graspers and sent to pathology. I use my diagram to show that if a colon polyp is seen, it can be removed using a grasper or wire snare. I usually draw a sessile polyp to demonstrate that some polyps have to be lifted up with saline injection to be safely removed though the colonoscope. I usually draw a tumor to illustrate that if I can’t remove it, I will be able to obtain a definitive biopsy. See Figure 30-1.

If any abnormalities are seen, biopsy samples can be obtained with small graspers and sent to pathology. I use my diagram to show that if a colon polyp is seen, it can be removed using a grasper or wire snare. I usually draw a sessile polyp to demonstrate that some polyps have to be lifted up with saline injection to be safely removed though the colonoscope. I usually draw a tumor to illustrate that if I can’t remove it, I will be able to obtain a definitive biopsy. See Figure 30-1.

I discuss the possible complications, including bleeding, perforation, and the risks of sedation.

I discuss the possible complications, including bleeding, perforation, and the risks of sedation.

I discuss the possibility of an incomplete exam due to technical problems. I let the patient know that proper visualization of the colon can be obscured if the prep isn’t excellent and stool is still present, and that some patients may have a tortuous colon, making it difficult to completely visualize the entire colon. I prepare the patient that if this is the case, the procedure will be terminated and the patient may be sent for a completion virtual colonoscopy (CT colonography) or barium enema.

I discuss the possibility of an incomplete exam due to technical problems. I let the patient know that proper visualization of the colon can be obscured if the prep isn’t excellent and stool is still present, and that some patients may have a tortuous colon, making it difficult to completely visualize the entire colon. I prepare the patient that if this is the case, the procedure will be terminated and the patient may be sent for a completion virtual colonoscopy (CT colonography) or barium enema.

From a patient’s point of view, preparation for colonoscopy requires the following:

Discuss proper follow-up. Explain what the patient should and can expect to feel after the procedure, and be sure to explain what symptoms should prompt a telephone call. Discuss how you will inform the patient regarding procedure findings and possible pathology reports. Determine whether this will be over the phone or during a follow-up office visit.

Figure 30-1 Colonoscopy

Professionalism

Demonstrate a Professional Image in Behavior

Patients who present with a fecal impaction are uncomfortable and seeking relief. Evacuating a fecal impaction is one of the least desired maneuvers a physician, resident, or medical student endures; however, it can also be one of the most rewarding. Successful disimpaction can result in significant relief for the patient, and the patient’s appreciation will be forthcoming. Whether this procedure is performed at the bedside or in the operating room under sedation, one must remain compassionate and professional throughout the process. Even though it is a topic that can provoke joking and laughter, all in attendance must remain courteous and respectful.

Systems-Based Practice

Screening Family Members for Disease

First-degree relatives of patients diagnosed with colon cancer are at an increased risk of developing colon cancer. If their family member was diagnosed over the age of 50 years, they should undergo their first colonoscopy at age 40 years. If the relative was diagnosed younger than age 50 years, they should be screened 10 years earlier than the age of diagnosis. Surveillance colonoscopies should be performed following the initial evaluation at set intervals dependent upon polyp detection and pathology results. However, repeat studies should be carried out at no longer than 5-year intervals, even if the exam is normal. This importance should be stressed to patients who have had colon cancer, so that they can inform their family members. Therefore, systems are set up in most office practices with reminder letters being sent out automatically to patients who are due for surveillance procedures.

She will be given at least two laxative doses the day before and/or the day of the procedure. I explain that this is important to clear the colon of any stool, so that I can visualize the entire colon.

She will be given at least two laxative doses the day before and/or the day of the procedure. I explain that this is important to clear the colon of any stool, so that I can visualize the entire colon. A rectal examination will be performed to feel for any internal rectal masses as well as to relax the anal sphincter.

A rectal examination will be performed to feel for any internal rectal masses as well as to relax the anal sphincter. Connect the small dashes, indicating how you might perform a biopsy on a tumor in the cecum (A) or sessile polyp (B) in the transverse colon, or snare a polyp on a stalk (C) in the left colon.

Connect the small dashes, indicating how you might perform a biopsy on a tumor in the cecum (A) or sessile polyp (B) in the transverse colon, or snare a polyp on a stalk (C) in the left colon. Once the colonoscope is at the beginning of the colon (cecum), the scope will be slowly withdrawn, paying careful attention to the lining of the colon.

Once the colonoscope is at the beginning of the colon (cecum), the scope will be slowly withdrawn, paying careful attention to the lining of the colon. I inform the patient that the risk of a perforation is in the range of 1 in 5000 to 10,000 and would require surgery for repair.

I inform the patient that the risk of a perforation is in the range of 1 in 5000 to 10,000 and would require surgery for repair. I also prepare her for the possibility that after the procedure she may feel bloated or have some abdominal distension. This is secondary to the air that is used to expand the lumen of the colon for proper visualization, although it may be reduced by the use of CO

I also prepare her for the possibility that after the procedure she may feel bloated or have some abdominal distension. This is secondary to the air that is used to expand the lumen of the colon for proper visualization, although it may be reduced by the use of CO To review the step-by-step preparation instructions for the procedure with a health professional a few days before the procedure so as to ensure that the prep is done properly. Though a routine procedure, it is probably a new and uncomfortable experience for the patient. To reduce anxiety about prep error, a “walk-through” of the prep is an opportunity to address any concerns or questions.

To review the step-by-step preparation instructions for the procedure with a health professional a few days before the procedure so as to ensure that the prep is done properly. Though a routine procedure, it is probably a new and uncomfortable experience for the patient. To reduce anxiety about prep error, a “walk-through” of the prep is an opportunity to address any concerns or questions. To have face-to-face contact with the physician who will be performing the colonoscopy. A caring encounter on the day of the procedure, blending confidence and compassion, goes a long way to add to the security a patient craves in preparing for the discomfort of the unknown.

To have face-to-face contact with the physician who will be performing the colonoscopy. A caring encounter on the day of the procedure, blending confidence and compassion, goes a long way to add to the security a patient craves in preparing for the discomfort of the unknown. To have a clear understanding of what to expect. The fewer surprises, the better. Compassionate description of the anticipated experience will allay most anxieties.

To have a clear understanding of what to expect. The fewer surprises, the better. Compassionate description of the anticipated experience will allay most anxieties.