Chapter 14 Constipation and diarrhoea

Constipation

Diarrhoea

Constipation

In Western populations, 90% of people defaecate between three times a day and once every 3 days. It is clear, therefore, that to base a definition of constipation on frequency alone is problematic. What is perceived to be constipation by one individual may be normal to another. Most definitions of constipation include infrequent bowel action of twice a week or less that involves straining to pass hard faeces and which may be accompanied by a sensation of pain or incomplete evacuation. A pragmatic definition would simply be the passage of hard stools less frequently than the patient’s own normal pattern. Standard criteria for the diagnosis of diarrhoea are available (Longstreth et al., 2006), although they are seldom used in practice.

Aetiology

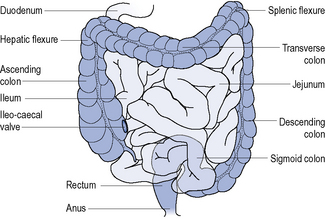

The digestive system can be divided into the upper and lower gastro-intestinal tract. The upper gastro-intestinal tract starts at the mouth and includes the oesophagus and stomach and isresponsible for the ingestion and digestion of food. The lower gastro-intestinal tract consists of the small intestine, large intestine (colon), rectum and anus (Fig. 14.1) and is responsible for the absorption of nutrients, conserving body water and electrolytes, drying the faeces and elimination.

Differential diagnosis

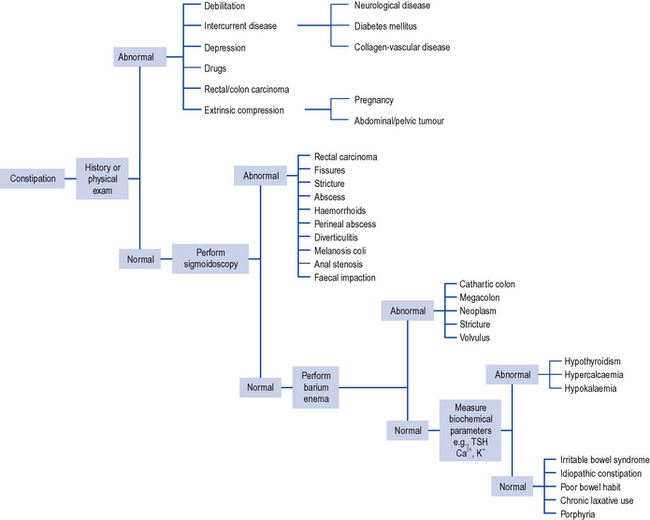

Constipation is a symptom and not a disease and can be caused by many different factors (Table 14.1) but the overwhelming majority of cases in non-elderly patients will be due to lack of dietary fibre. To aid diagnosis, questions need to be asked about the frequency and consistency of stools, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, distension, discomfort, mobility, diet and other concurrent symptoms or disorders the patient may be experiencing. It may also be necessary to ask about access to a toilet or commode. The individual with limited mobility may suppress the urge to defaecate because of difficulty in getting to the toilet. Likewise, lack of privacy or dependency on a nurse or carer for toileting may result in urge suppression that precipitates constipation or exacerbates an underlying predisposition. Patients with unexplained constipation of recent onset or a sudden aggravation of existing constipation associated with abdominal pain and the passage of blood or mucus, and long-standing constipation unresponsive to treatment require further investigation. Investigations include sigmoidoscopy/colonoscopy, barium enema, full blood count and biochemical monitoring including thyroid function tests (Fig. 14.2).

| Cause | Comment |

|---|---|

| Poor diet | Diets high in animal fats, for example, meats, dairy products, eggs, and refined sugar, for example, sweets, but low in fibre predispose to constipation |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Spasm of colon delays transit of intestinal contents. Patients have a history of alternating constipation and diarrhoea |

| Poor bowel habit | Ignoring and suppressing the urge to have a bowel movement will contribute to constipation |

| Laxative abuse | Habitual consumption of laxatives necessitates increase in dose over time until intestine becomes atonic and unable to function without laxative stimulation |

| Travel | Changes in lifestyle, daily routine, diet and drinking water may all contribute to constipation |

| Hormone disturbances | For example, hypothyroidism, diabetes. Other clinical signs should be more prominent, for example, lethargy and cold intolerance in hypothyroidism and increased urination and thirst in diabetes |

| Pregnancy | Mechanical pressure of womb on intestine and hormonal changes, for example, high levels of progesterone |

| Fissures and haemorrhoids | Painful disorders of the anus often lead patients to suppress defaecation, leading to constipation |

| Diseases | Many disease states may have constipation as a symptom, for example, scleroderma, lupus, multiple sclerosis, depression, Parkinson’s disease, stroke |

| Mechanical compression | Scarring, inflammation around diverticula and tumours can produce mechanical compression of intestine |

| Nerve damage | Spinal cord injuries and tumours pressing on the spinal cord affect nerves that lead to intestine |

| Colonic motility disorders | Peristaltic activity of intestine may be ineffective, resulting in colonic inertia |

| Medication | See Table 14.2 |

| Dehydration | Insufficient fluid intake or excessive fluid loss. Water and other fluids add bulk to stools, making bowel movements soft and easier to pass |

| Immobility | Prolonged bedrest after an accident, during an illness or general lack of exercise |

| Electrolyte abnormalities | Hypercalcaemia, hypokalaemia |

General management

If the patient is taking medication for a concurrent disorder this must be assessed for its propensity to cause constipation. In the UK, over 700 medicinal products, including ophthalmic preparations, have constipation listed as a possible side effect. Common examples of medicines involved are presented in Table 14.2.

Table 14.2 Examples of medicines known to cause constipation (frequency defined as very common [>10%] or common [1–10%])

| α-Blocker | Prazosin |

| Antacid | Aluminium and calcium salts |

| Anticholinergic | Trihexyphenidyl, hyoscine, oxybutynin, procyclidine, tolterodine |

| Antidepressant | Tricyclics, SSRIs, reboxetine, venlafaxine, duloxetine, mirtazepine |

| Antiemetic | Palonosetron, dolasetron, aprepitant |

| Antiepileptic | Carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine |

| Antipsychotic | Phenothiazines, haloperidol, pimozide and atypical antipsychotics such as amisulpride, aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, zotepine, clozapine |

| Antiviral | Foscarnet |

| β-Blocker | Oxprenolol, bisoprolol, nebivolol; other β-blockers cause constipation more rarely |

| Bisphosphonate | Alendronic acid |

| CNS stimulant | Atomoxetine |

| Calcium channel blocker | Diltiazem, verapamil |

| Cytotoxic | Bortezomib, buserelin, cladribine, docetaxel, doxorubicin, exemestane, gemcitabine, irinotecan, mitozantrone, pentostatin, temozolomide, topotecan, vinblastine, vincristine, vindesine, vinorelbine |

| Dopaminergic | Amantadine, bromocriptine, carbegolide, entacapone, tolcapone, levodopa, pergolide, pramipexole, quinagolide |

| Growth hormone antagonist | Pegvisomant |

| Immunosuppressant | Basiliximab, mycophenolate, tacrolimus |

| Lipid-lowering agent | Colestyramine, colestipol, rosuvastatin, atorvastatin (other statins uncommon) gemfibrozil |

| Iron | Ferrous sulphate |

| Metabolic disorder | Miglustat |

| Muscle relaxant | Baclofen |

| NSAID | Meloxicam; other NSAIDs, for example, aceclofenac, and COX-2 inhibitors reported as uncommon |

| Smoking cessation | Bupropion |

| Opioid analgesic | All opioid analgesics and derivatives |

| Ulcer healing | All proton pump inhibitors, sucralfate |

Non-drug treatment

Non-drug treatment is advocated as first-line therapy for all patient groups, except those who are terminally ill. This often includes advising an increase in fluid intake at the same time as reducing strong or excessive intake of tea or coffee, since these act as a diuretic and serve to make constipation worse.It is generally recommended that fibre intake in the form of fruit, vegetables, cereals, grain foods, wholemeal bread, etc. be increased to about 30 g/day. The amounts of fibre in commonly eaten foods have been published (MeReC, 2004). Such a diet should be tried for at least 1 month to determine if it has an effect. Most will notice an effect within 3–5 days. Unfortunately, a high-fibre diet is not without problems, with patients complaining of flatulence, bloating and distension, although these effects should diminish over a period of several months. Patients who increase their fibre intake must also be advised to drink 2 L of water a day. Where an intake of this volume cannot be ingested it will be necessary to avoid increasing dietary fibre. An increased level of exercise should also accompany the raised fibre intake as this is thought to help relax and contract the abdominal muscles and help food move more efficiently through the gut.

Drug treatment

Drug treatment is indicated where there is faecal impaction, constipation associated with illness, surgery, pregnancy, poor diet, where the constipation is drug induced, where bowel strain is undesirable, and as part of bowel preparation for surgery. The various laxatives available can be classified as bulk forming, stimulant, osmotic and faecal softeners. A systematic review (Tramonte et al., 1997) identified 36 trials involving 1815 participants that met their inclusion criteria. Twenty of the trials compared laxative against placebo or regular diet, 13 of which demonstrated statistically significant increases in bowel movement. The remaining 16 trials compared different types of laxatives with each other. The review concluded that laxative use was superior to placebo but due to a lack of comparative data could not conclude which laxative group was most efficacious. Further, more recent reviews have found good evidence that macrogols are effective, as are ispaghula husk and bisacodyl, although data is still lacking on which laxative is best (Frizelle and Barclay, 2007).

Diarrhoea

Aetiology

Many medicines, particularly broad-spectrum antibiotics such as ampicillin, erythromycin and neomycin, induce diarrhoea secondary to therapy (Table 14.3). With these antibiotics the mechanism involves the overgrowth of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and fungi in the large bowel after several days of therapy. The diarrhoea is generally self-limiting. However, when the overgrowth involves Clostridium difficile and the associated production of its bacterial toxin, life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis may be the outcome.

Table 14.3 Examples of medicines known to cause diarrhoea (defined as very common [>10%] or common [1–10%])

| α-Blocker | Prazosin |

| ACE inhibitor | Lisinopril, perindopril |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | Telmisartan |

| Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine |

| Antacid | Magnesium salts |

| Antibacterial | All |

| Antidiabetic | Metformin, acarbose |

| Antidepressant | SSRIs, clomipramine, venlafaxine |

| Antiemetic | Aprepitant, dolasetron |

| Antiepileptic | Carbamazepine, oxcarbagepine, tiagabine, zonisamide, pregabalin, levtiracetam |

| Antifungal | Caspofungin, fluconazole, flucytosine, nystatin (in large doses), terbinafine, voriconazole |

| Antimalarial | Mefloquine |

| Antiprotozoal | Metronidazole, sodium stibogluconate |

| Antipsychotic | Aripiprazole |

| Antiviral | Abacavir, emtricitabine, stavudine, tenofovir, zalcitabine, zidovudine, amprenavir, atazanavir, indinavir, lopinavir, nelfinavir, saquinavir, efavirinez, ganciclovir, valganciclovir, adefovir, oseltamivir, ribavrin, fosamprenavir |

| β-Blocker | Bisoprolol, carvedilol, nebivolol |

| Bisphosphonate | Alendronic acid, disodium etidronate, ibandronic acid, risedronate, sodium clodronate, disodium pamidronate, tiludronic acid |

| Cytokine inhibitor | Adalimumab, infliximab |

| Cytotoxic | All classes of cytotoxics |

| Dopaminergic | Levodopa, entacapone |

| Growth hormone antagonist | Pegvisomant |

| Immunosuppressant | Ciclosporin, mycophenolate, leflunomide |

| NSAID | All |

| Ulcer healing | All proton pump inhibitors |

| Vaccine | Pediacel (5 vaccines in 1), haemophilus, meningococcal |

| Miscellaneous | Calcitonin, strontium ranelate, colchicine, dantrolene, olsalazine, anagrelide, nicotinic acid, pancreatin, eplerenone, acamprosate |

Signs and symptoms

Dehydration is a common problem in the very young and frail elderly and the signs and symptoms must be recognised.In children, the severity of dehydration is most accurately determined in terms of weight loss as a percentage of body weight prior to the dehydrating episode. Unfortunately, in the clinical situation pre-illness weight is rarely known; therefore, clinical signs of dehydration must be assessed. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) has issued guidance on assessing the level of dehydration in children under 5 years of age and appropriate fluid management depending on the level of dehydration. Symptoms that could indicate mild dehydration are vague and include tiredness, anorexia, nausea and light-headedness.

Treatment

General measures

Patients should be advised on handwashing and other hygiene-related issues to prevent transmission to other family members. Promotion of handwashing has been shown to decrease diarrhoeal episodes by approximately one-third (Ejemot et al., 2008). Exclusion from work or school until the patient is free of diarrhoea is advised. In acute, self-limiting diarrhoea, children, healthcare workers and food handlers should be symptom free for 48 h before returning to school or work. More exacting criteria for return to work, such as testing for negative stool samples, are rarely required.

In both children and adults, normal feeding should be restarted as soon as possible. In weaned and non-weaned children with gastroenteritis, early feeding after rehydration has been shown to result in higher weight gain, no deterioration or prolongation of the diarrhoea and no increase in vomiting or lactose intolerance (Conway and Ireson, 1989, Sandhu et al., 1997). Similarly, breast-feeding infants should continue to feed throughout the rehydration and maintenance phases of therapy. Avoidance of milk or other lactose-containing food is seldom justified.

Dehydration treatment

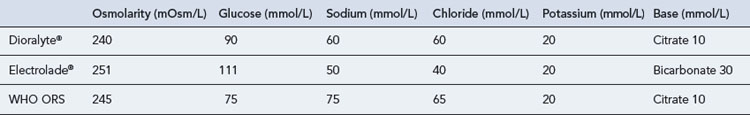

Young children and the frail elderly are prone to diarrhoea-induced dehydration and use of an oral rehydration solution (ORS) is recommended. The formula recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) contains glucose, sodium, potassium, chloride and bicarbonate in an almost isotonic fluid. A number of similar preparations are available commercially in the form of sachets that require reconstitution in clean water before use (Table 14.4). Glucose concentrations between 80 and 120 mmol/L are needed to optimise sodium absorption in the small intestine. Glucose concentrations in excess of 160 mmol/L will cause an osmotic gradient that will result in increased fluid and electrolyte loss. High sodium solutions, in excess of 90 mmol/L, may lead to hypernatraemia, especially in children, and should be avoided. Until recently, the WHO ORS contained 90 mmol/L sodium, as cholera is more common in developing countries and associated with rapid loss of sodium and potassium. However, a systematic review of trials using a reduced osmolarity ORS (Hahn et al., 2002) concluded that solutions with a reducedosmolarity compared to the standard WHO formula were associated with fewer unscheduled intravenous infusions, a trend towards reduced stool output and less vomiting in children with mild-to-moderate diarrhoea. Based on this and other findings, the WHO ORS now has a reduced osmolarity of 245 mOsm/L and contains 75 mmol of sodium.

Commercially available solutions in the UK contain lower sodium concentrations as diarrhoea tends to be isotonic, and therefore replacement of large quantities of sodium is less important and indeed may be harmful. The presence of potassium prevents hypokalaemia occurring in the elderly, especially in those taking diuretics. ORS should be routinely used in both primary and secondary care settings. There appears to be no significant difference between intravenous and oral rehydration (Gavin et al., 1996).

For healthy adults, an appropriate substitute for a rehydration sachet is 1 level teaspoonful of table salt plus 1 tablespoon of sugar in 1 L of drinking water. The volume of ORS to be taken in treating mild-to-moderate diarrhoea is dependent on age. In adults, 2 L of oral rehydration fluid should be given in the first 24 h, followed by unrestricted normal fluids with 200 mL of rehydration solution per loose stool or vomit. For children, 30–50 mL/kg of an ORS should be given over 3–4 h. This can be followed with unrestricted fluids, either with normal fluids alternating with ORS or normal fluids with 10 mL/kg rehydration solution after each loose stool or vomit (Murphy, 1998). The solution is best sipped every 5–10 min rather than drunk in large quantities less frequently.

Care is required in diabetic patients who may need to monitor blood glucose levels more carefully.

Drug treatment

Antimicrobials

Antibiotics are generally not recommended in diarrhoea associated with acute infective gastroenteritis. Inappropriate use will only contribute further to the problem of resistant organisms. There is, however, a place for antibiotics in patients with positive stool culture where the symptoms are not receding or for travellers’ diarrhoea (De Bruyn et al., 2000). In patients presenting with dysentery or suspected exposure to bacterial infection, treatment with a quinolone, for example, ciprofloxacin, may be appropriate. However, quinolones are not without their problems: they may cause tendon damage or induce convulsions in epileptics, in situations that predispose to seizures, and in patients taking NSAIDs. Their use in adolescents is also not recommended because of an association with arthropathy.

Probiotics

Probiotics have been defined as components of microbial cells or microbial cell preparations that have a beneficial effect on health. Well-known probiotics include lactic acid bacteria and the yeast Saccharomyces. The rationale for their use in infectious diarrhoea is that they act against enteric pathogens by competing for available nutrients and binding sites, making gut contents acid and increasing immune responses. A Cochrane review (Allen et al., 2003) concluded that whilst probiotics in individual studies appeared moderately effective as adjunctive therapy, there were insufficient studies of specific probiotic regimens to inform the development of evidence-based treatment guidelines.

Zinc

The use of zinc has been reviewed in the treatment of diarrhoea in children in developing countries (Lazzerini et al., 2008). In this context, zinc has been shown to be of value in children older than 6 months, probably because they have some prior, underlying deficiency of zinc.

Rotavirus vaccine

Rotavirus vaccine has been shown to protect against the most common strains of rotavirus (G1 and G3), although the benefits of the vaccine are dependant on the type of vaccine used, with rhesus and human rotavirus the most efficacious (Soares-Weiser, 2004).

Some of the common therapeutic problems in the management of individuals with constipation and diarrhoea are outlined in Table 14.5.

Table 14.5 Common therapeutic problems in constipation and diarrhoea

| Problem | Comment |

|---|---|

| Constipation | |

| Bulk laxative, for example ispaghula, taken at bedtime | Drugs such as ispaghula should not be taken before going to bed because of risk of oesophageal blockage |

| Urine changes colour | Anthraquinone glycosides, for example senna, are excreted by the kidney and may colour urine yellowish-brown to red colour, depending on pH |

| Patient claims dietary and fluid advice ineffective in resolving constipation | May find high-fibre diet difficult to adhere to, socially unacceptable, and expect result in less than 4 weeks |

| Patient taking docusate complains of unpleasant aftertaste or burning sensation | Advise to take with plenty of fluid after ingestion |

| Sterculia as Normacol® and Normacol Plus® granules or sachets | The granules should be placed dry on the tongue and swallowed immediately with plenty of water or a cool drink. They can also be sprinkled onto and taken with soft food such as yoghurt |

| Methylcellulose (Celevac®) | Each tablet should be taken with at least 300 mL of liquid |

| Diarrhoea | |

|---|---|

| Antimotility agent requested for a young child | Antimotility agents must be avoided in young children or patients with severe gastroenteritis or dysentery |

| Antimotility agent requested by patient with persistent diarrhoea (>10 days) | Antimotility agent inappropriate. Stool culture required to exclude parasitic infection such as Giardia, Entamoeba and Cryptosporidium |

| Adult with diarrhoea stops eating and drinking to allow diarrhoea to settle | Patient should eat and drink as normally as possible. Plenty of fluids required to prevent dehydration. Fruit juice (glucose and potassium), soup (salt), bread and pasta (carbohydrate) are of particular benefit |

| Reconstitution of oral rehydration solution | Each sachet of Diorolyte® and Electrolade® requires 200 mL of water. They should be discarded after 1 h after preparation unless stored in a fridge when they may be kept for 24 h |

Answers

Answers

Allen S.J., Okoko B., Martinez E., et al. Probiotics for treating infectious diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (4):2003. Art No. CD003048. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003048.pub2

Conway S.P., Ireson A. Acute gastroenteritis in well nourished infants: comparison of four feeding regimens. Arch. Dis. Child. 1989;64:87-91.

De Bruyn G., Hahn S., Borwick A. Antibiotic treatment for travellers’ diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (3):2000. Art. No. CD002242. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002242

Ejemot R.I., Ehiri J.E., Meremikwu M.M., et al. Hand washing for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (1):2008. Art. No. CD004265. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004265.pub2

Frizelle F., Barclay M. Constipation in Adults. London: Clinical Evidence. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2007. Available at http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/ceweb/index.jsp

Gavin N., Merrick N., Davidson B. Efficacy of glucose-based oral rehydration therapy. Pediatrics. 1996;98:45-51.

Hahn S., Kim Y., Garner P. Reduced osmolarity oral rehydration solution for treating dehydration due to diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (1):2002. Art No. CD002847. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002847

Lazzerini M., Ronfani L. Oral zinc for treating diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (3):2008. Art No. CD005436. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005436.pub2

Longstreth G.F., Thompson W.G., Chey W.D., et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491.

MeReC. Approximate dietary fibre content of selected foods. MeReC Bull.. 2004;14(Suppl. 6):1.

Murphy M.S. Guidelines for managing acute gastroenteritis based on a systematic review of published research. Arch. Dis. Child. 1998;79:279-284.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Diarrhoea and Vomiting in Children: Diarrhoea and Vomiting Caused by Gastroenteritis: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management in Children Younger than 5 Years, Clinical Guideline 84. London: NICE. 2009. Available at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11846/43815/43815.doc

Sandhu B.K., Isolauri E., Walker-Smith J.A., et al. A multicentre study on behalf of the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition Working Group on Acute Diarrhoea: early feeding in childhood gastroenteritis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr.. 1997;24:522-527.

Soares-Weiser K., Goldberg E., Tamimi G., et al. Rotavirus vaccine for preventing diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (1):2004. Art No. CD002848. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002848.pub2

Tramonte S.M., Brand M.B., Mulrow C.D., et al. The treatment of chronic constipation in adults. A systematic review. J. Gen. Int. Med.. 1997;12:15-24.

Alonso-Coello P., Guyatt G., Heels-Ansdell D., et al. Laxatives for the treatment of hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (4):2005. Art No. CD004649. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004649.pub2

Bartlett J.G. Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2002;346:334-339.

Borum M.L. Constipation: evaluation and management. Prim. Care. 2001;28:577-590.

Dupont H.L. Systematic review: the epidemiology and clinical features of travellers’ diarrhoea. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.. 2009;30:187-196.

Khin M.U., Nyunt-Nyunt W., Khin M., et al. Effect on clinical outcome of breast feeding during acute diarrhoea. Br. Med. J.. 1985;290:587-589.

Pappagallo M. Incidence, prevalence and management of opioid bowel dysfunction. Am. J. Surg.. 2001;182(Suppl. 5A):115-185.

Sellin J.H. The pathophysiology of diarrhoea. Clin. Transplant.. 2001;15(Suppl. 4):2-10.

Xing J.H., Soffer E.E. Adverse effects of laxatives. Dis. Colon. Rectum.. 2001;44:1201-1209.