Consent and Information for Patients

CONSENT AS AN ACTIVE PROCESS

Information

There is no statute which clearly defines what information should be given to patients about anaesthesia, and different countries’ legal systems have taken slightly divergent views. The AAGBI guidance is shown in Table 19.1. It must be emphasized that the anaesthetist should adapt this to the individual patient and surgery. For instance, visual loss after prone surgery is a rare but significant procedure-related complication which is relevant to specific patients.

TABLE 19.1

AAGBI Guidance on Information Which Should be Provided to Patients Relating to Anaesthesia

Generally what may be expected as part of the proposed anaesthetic technique. For example, fasting, the administration and effects of premedication, transfer from the ward to the anaesthetic room, cannula insertion, noninvasive monitoring, induction of general and/or local anaesthesia, monitoring throughout surgery by the anaesthetist, transfer to a recovery area, and return to the ward. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesia, fluids and antiemetic therapy should also be described.

Generally what may be expected as part of the proposed anaesthetic technique. For example, fasting, the administration and effects of premedication, transfer from the ward to the anaesthetic room, cannula insertion, noninvasive monitoring, induction of general and/or local anaesthesia, monitoring throughout surgery by the anaesthetist, transfer to a recovery area, and return to the ward. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesia, fluids and antiemetic therapy should also be described.

Postoperative recovery in a critical care environment (and what this might entail), where appropriate.

Postoperative recovery in a critical care environment (and what this might entail), where appropriate.

Alternative anaesthetic techniques, where appropriate.

Alternative anaesthetic techniques, where appropriate.

Commonly occurring, ‘expected’ side-effects, such as nausea and vomiting, numbness after local anaesthetic techniques, succinylcholine pains and post-dural puncture headache.

Commonly occurring, ‘expected’ side-effects, such as nausea and vomiting, numbness after local anaesthetic techniques, succinylcholine pains and post-dural puncture headache.

Rare but serious complications such as awareness (with and without pain), nerve injury (for all forms of anaesthesia), disability (stroke, deafness and blindness) should be provided in written information, as should the very small risk of death.

Rare but serious complications such as awareness (with and without pain), nerve injury (for all forms of anaesthesia), disability (stroke, deafness and blindness) should be provided in written information, as should the very small risk of death.

It is good practice to include an estimate of the incidence of the risk. Anaesthetists must be prepared to discuss these risks at the preoperative visit if the patient asks about them.

It is good practice to include an estimate of the incidence of the risk. Anaesthetists must be prepared to discuss these risks at the preoperative visit if the patient asks about them.

Specific risks or complications that may be of increased significance to the patient, for example, the risk of vocal cord damage if the patient is a professional singer.

Specific risks or complications that may be of increased significance to the patient, for example, the risk of vocal cord damage if the patient is a professional singer.

The increased risk from anaesthesia and surgery in relation to the patient’s medical history, nature of the surgery and urgency of the procedure. If possible, an estimate of the additional risk should be provided.

The increased risk from anaesthesia and surgery in relation to the patient’s medical history, nature of the surgery and urgency of the procedure. If possible, an estimate of the additional risk should be provided.

The risks and benefits of local and regional anaesthesia in comparison to other analgesic techniques.

The risks and benefits of local and regional anaesthesia in comparison to other analgesic techniques.

The risk of intra-operative pain, and the need to convert to general anaesthesia, should a proposed local or regional technique be inadequate or ineffective. The risks and benefits of adjunctive sedation or general anaesthesia should be discussed.

The risk of intra-operative pain, and the need to convert to general anaesthesia, should a proposed local or regional technique be inadequate or ineffective. The risks and benefits of adjunctive sedation or general anaesthesia should be discussed.

The benefits and risks of associated procedures such as central venous catheterization, where appropriate.

The benefits and risks of associated procedures such as central venous catheterization, where appropriate.

Techniques of a sensitive nature, such as the insertion of an analgesic suppository.

Techniques of a sensitive nature, such as the insertion of an analgesic suppository.

Communicating Risk

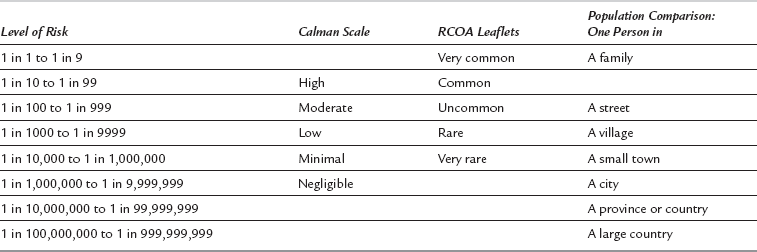

Patients prefer to be given numerical estimates of risk; doctors prefer to provide less precise qualitative estimates. Given the current state of evidence, neither is more accurate. The risk to the individual patient is usually unknown with sufficient precision. There is reasonable evidence that patients (and doctors) do not have sufficient understanding of probabilities for these to be used alone. Verbal likelihood scales are therefore most commonly used. The problem lies in the interpretation by anaesthetist and patient of the scale. ‘Never’ and ‘always’ are straightforward, but ‘common’, ‘rare’ and ‘unusual’ are subjective terms. Even within anaesthesia information systems, these are used differently. Drug information uses the ‘Calman’ scale; the Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCOA) uses a different scale. In order to provide more personal context, the population scale is sometimes used, comparing the risk to the number of people on a street, village, town, etc. (Table 19.2).

Capacity

1. Adult patients are assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity. Capacity is the ability to (a) understand and remember the information and (b) use it to arrive at a decision.

2. Patients must be given a reasonable chance to demonstrate their capacity. A person’s lack of capacity cannot be assumed solely because they have taken drugs, alcohol or premedication, nor because they are making seemingly ‘wrong’ choices. In particular, the inability to communicate verbally does not imply a lack of capacity. Doctors (including anaesthetists) must make reasonable attempts to provide information for the patient so that they can decide on treatment options for themselves.

3. The treatment of adults without capacity must be in their best interests. This is a wider definition of best interests than solely medical best interests. Although generally more relevant to critical care than anaesthesia, the Act is clear that the treatment must be necessary, the least restrictive and in the patient’s wider best interests.

4. Patients may appoint proxy decision-makers with Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA). These individuals have the legal right to give or receive consent on behalf of a patient without capacity for carrying out or continuation of treatment. The exception is for life-sustaining treatment or treatment considered inappropriate by the doctor.

at the time of the directive, the patient makes the decision voluntarily, with adequate information, and they have capacity

at the time of the directive, the patient makes the decision voluntarily, with adequate information, and they have capacity

the specific refusal is clear, e.g. blood transfusion

the specific refusal is clear, e.g. blood transfusion

the circumstances of when the refusal should apply are clear, e.g. resuscitation may be accepted after witnessed cardiac arrest, but not following a disabling stroke.

the circumstances of when the refusal should apply are clear, e.g. resuscitation may be accepted after witnessed cardiac arrest, but not following a disabling stroke.