Anaesthesia for the Patient with a Transplanted Organ

INTRODUCTION

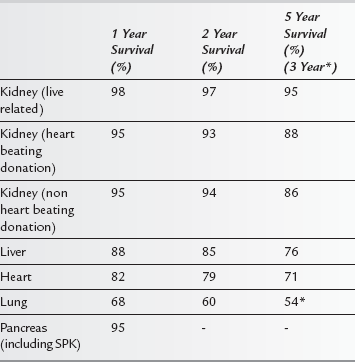

There have been several advances in surgical techniques, perioperative management and immunosuppressive regimens to prevent early and late organ rejection. These have led to improvements in short and long-term outcomes after transplantation, with most patients now able to lead a relatively normal life (see Table 39.1). Furthermore, outcomes following patient re-transplantation after rejection or graft failure have improved. As a result, it is likely that non-transplant anaesthetists are more likely to encounter transplant recipients presenting for elective surgery in the future. Transplant recipients are more likely than the general population to require surgery for malignancy or emergency procedures especially for acute gastrointestinal pathology. In addition, the increased success of solid organ transplantation has led to the recipient population being older and having more comorbidities than previously. Furthermore, the use of ‘marginal’ donor organs, secondary to the relative shortage of organs, is likely to make the management of these patients more complex. In general, wherever recipients present for non-transplant surgery, the patient is likely to have both residual evidence of chronic disease, be immunocompromised and have reduced organ function. In the emergency situation, the effect of acute illness may also complicate further anaesthetic management.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

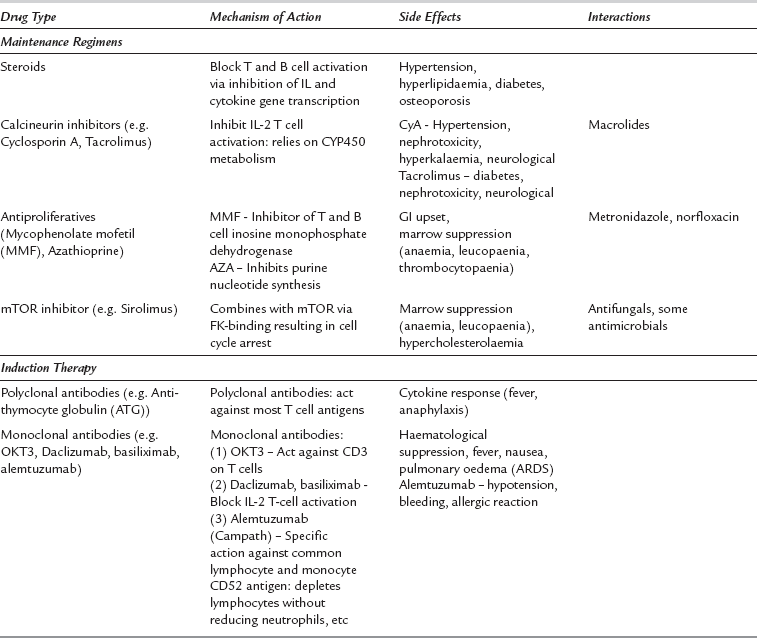

induction therapies – to reduce both early rejection episodes and complications associated with long-term treatments using either high dose conventional immunosuppressive agents or polyclonal/monoclonal antibodies.

induction therapies – to reduce both early rejection episodes and complications associated with long-term treatments using either high dose conventional immunosuppressive agents or polyclonal/monoclonal antibodies.

maintenance treatments – to prevent chronic rejection episodes with reduced dose therapies.

maintenance treatments – to prevent chronic rejection episodes with reduced dose therapies.

The characteristics, side effects and drug interactions of the main immunosuppressive agents are shown in Table 39.2.

increased risk of infection (see Table 39.3) – all staff should be aware of the risks of opportunistic infections and take appropriate precautions, including aseptic techniques and microbiological monitoring.

increased risk of infection (see Table 39.3) – all staff should be aware of the risks of opportunistic infections and take appropriate precautions, including aseptic techniques and microbiological monitoring.

TABLE 39.3

Organisms Causing Common Opportunistic Infections in Transplant Recipients

CMV (cytomegalovirus)

Fungi – Aspergillus sp, Candida sp

Pneumocystis sp

Legionella sp

Toxoplasma sp

Listeria sp

reduced wound healing – long-term immunosuppression also reduces the tensile strength of tissues and therefore may impair wound healing.

reduced wound healing – long-term immunosuppression also reduces the tensile strength of tissues and therefore may impair wound healing.

major drug interactions – immunosuppressive drugs can cause interactions with a number of medications used for anaesthesia or postoperative pain relief.

major drug interactions – immunosuppressive drugs can cause interactions with a number of medications used for anaesthesia or postoperative pain relief.

ANAESTHETIC CONSIDERATIONS

SPECIFIC ISSUES

Indications for Renal Transplantation

Typical indications for renal transplantation include:

diabetic nephropathy (often combined as simultaneous kidney–pancreas transplant)

diabetic nephropathy (often combined as simultaneous kidney–pancreas transplant)

The effects of renal transplantation on quality of life issues are profound: most recipients are rendered dialysis-free. However, any systemic complications already present as a component of renal disease may continue to pose problems. Patients presenting for surgery may retain diabetic-related illnesses, ischaemic heart disease, hypertension and pulmonary disease. They are also maintained on relatively severe immunosuppressive regimens with the risk of adverse effects (Table 39.2).

Liver

Cardiac

Anaesthetic Considerations

Intraoperatively, the use of regional anaesthesia is somewhat controversial but where there is normal cardiac function, it is unlikely to cause major complications. Right internal jugular vein cannulation is best avoided since it provides venous access for frequent myocardial biopsies. Drugs affecting the autonomic system are of minimal use in these patients due to the denervation occurring after heart transplantation. A requirement for an increased chronotropic or inotropic effect requires the use of direct-acting drugs including dobutamine, ephedrine and noradrenaline. Drugs that have direct action on heart allografts are shown in Table 39.4.

TABLE 39.4

Drugs that have Direct Action on Heart Allografts

| Direct-Acting Drugs – Retained Action on Denervated Heart | No Activity on Denervated Heart |

| Dobutamine | Atropine, Glycopyrrolate |

| Ephedrine | Neostigmine |

| Dopamine | Pancuronium |

| Glugacon | Pyridostigmine |

| Digoxin | |

| Adrenaline | |

| Noradrenaline | |

| Beta-blockers | |

| Phosphodiesterase inhibitors |