4 Conscious Sedation for Interventional Pain Procedures

Conscious Sedation

Conscious sedation is an older term from 1985 to describe lightly sedated dental patients.1 It is defined as the sedation depth that permits appropriate response to physical stimulation or verbal command (e.g., “open your eyes”). Many groups, including the American Association of Anesthesiology and American College of Emergency Physicians believe that the term conscious sedation is imprecise and they propose terms such as sedation/analgesia2 or procedural sedation and analgesia (PSAA),1 or monitored anesthesia care (MAC).3 Indeed, in the first ASA guidelines from February 1996, a notable comment is that patients whose only response is reflex withdrawal from a painful stimulus are sedated to a greater degree than encompassed by sedation/analgesia.

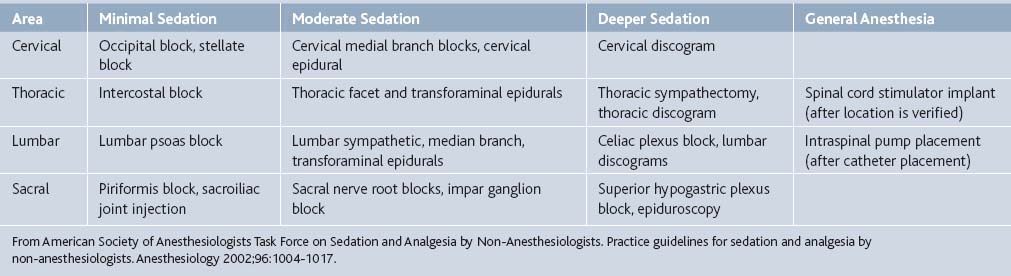

A continuum of depth of sedation was described in the second ASA guidelines for sedation/analgesia.4 From Table 4-1, concepts ranging from minimal sedation (anxiolysis) through moderate sedation/analgesia (conscious sedation) to general anesthesia are described related to responsiveness and airway management. Of note, moderate sedation/analgesia is described as purposeful response to verbal or tactile stimulation and that no airway intervention is required. A more detailed sedation continuum (Table 4-1) is proposed in a Canadian Emergency Department consensus guideline.5 However, the transition between moderate sedation and deep sedation where airway management is required can be different with each patient.

The best approach is to establish a sedation/analgesia plan prior to starting the procedure. Optimal goals include the following6:

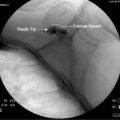

In addition, the complexity and duration of the procedure involved changes the sedation/analgesia plan. Simple and short procedures may require little or no sedation with only local or topical analgesia, such as trigger point injections or piriformis muscle injections. Many procedures requiring fluoroscopic guidance can be assisted with moderate sedation including midazolam and fentanyl. Although some interventional pain experts routinely perform medial branch blocks under local analgesia only, multiple-level procedures versus single-level procedures may require more than midazolam 2 mg and fentanyl 100 mcg IV, particularly at a training institution. Cancer neurolytic blocks that can be intensely stimulating often require deeper sedation. Prolonged sedation may be required for spinal cord stimulation trials or intrathecal catheter implants due to the duration of the procedure (see Table 4-1). Physician preparation and experience can decrease the duration of the procedure, thereby decreasing the need for sedation and analgesia.

Patient Preparation

One of the main ways of decreasing sedation and analgesia requirements is to prepare patients for what happens during the procedure and hence reducing their anxiety of the unknown. It is easiest for those patients who are returning for a series of the same procedure. Short procedural materials or websites describing the procedure can help patients with questions in the office or preoperative area. Although the literature is insufficient in supporting preprocedural preparation, the ASA consultants agree that “appropriate preprocedure counseling of patients regarding risks, benefits, and alternatives to sedation and analgesia increases patient satisfaction.”4

| Class | Systemic Disturbance | Mortality |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Healthy patient with no disease outside of the surgical process | <0.03% |

| 2 | Mild-to-moderate systemic disease caused by the surgical condition or by other pathologic processes | 0.2% |

| 3 | Severe disease process that limits activity but is not incapacitating | 1.2% |

| 4 | Severe incapacitating disease process that is a constant threat to life | 8% |

| 5 | Moribund patient not expected to survive 24 hours with or without an operation | 34% |

| E | Suffix to indicate an emergency surgery for any class | Increased |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

From Cohen MM, Duncan PG, Tate RB: Does anesthesia contribute to operative mortality? JAMA 1988;260:2859-2863.

Because interventional pain procedures are almost always elective, particularly for chronic pain patients, ASA fasting guidelines should be observed as per Table 4-3. Of note, patients can have a small amount of clear liquids up to 2 hours prior to procedure. Otherwise, many surgery centers will allow the procedure to be performed only under local or topical analgesia.4

Table 4-3 Summary of ASA Preprocedure Fasting Guidelines∗

| Ingested Material | Minimum Fasting Period† |

|---|---|

| Clear liquids‡ | 2 hr |

| Breast milk | 4 hr |

| Infant formula | 6 hr |

| Nonhuman milk§ | 6 hr |

| (Light meal) | 6 hr |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

(A light meal typically consists of toast and clear liquids. Meals that include fried or fatty foods or meat may prolong gastric emptying time. Both the amount and type of foods ingested must be considered when determining an appropriate fasting period.)

∗ These recommendations apply to healthy patients who are undergoing elective procedures. They are not intended for women in labor. Following the Guidelines does not guarantee a complete gastric emptying has occurred.

† The fasting periods apply to all ages.

‡ Examples of clear liquids include water, fruit juices without pulp, carbonated beverages, clear tea, and black coffee.

§ Since nonhuman milk is similar to solids in gastric emptying time, the amount ingested must be considered when determining an appropriate fasting period.

From American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 2002;96:1004-1017.

Medical morbid conditions, particularly cardiopulmonary disease, can be problematic for a nonanesthesiologist providing sedation. A history of sleep apnea and difficult airway physical habitus as specified by Table 4-4 may suggest less sedation or having a monitoring anesthesiologist for the procedure would be appropriate.

Table 4-4 Airway Assessment for Sedation and Analgesia

From American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 2002;96:1004-1017.

Allergies

Latex and iodine allergies can be easily prevented with advanced notice. Most interventional pain procedures can document correct placement fluoroscopically without contrast patterns and by anatomical landmarks. Surface preparation solutions, such as chlorhexidine can be used instead. Indeed, the authors routinely use chlorhexidine because some literature suggests that it may be the best antiseptic for regional and interventional pain procedures.8

Most local anesthetic allergies are caused by amide local anesthetic compounds, such as lidocaine or bupivacaine. Some patients also describe an allergy from a combination of these agents mixed with epinephrine. Often the epinephrine in a prior event was absorbed intravascularly causing an increase in heart rate. An alternative to using amide local anesthetics are esters: chloroprocaine or procaine. The main question to ask is whether the patient had a “true” allergic reaction with skin rash, throat tightness, difficulty breathing or swallowing. If the patient has a rash caused by benzocaine, a common ester local anesthetic in suntan lotions, the patient may be allergic to esters. Typically, patients are allergic to one chemical structure of local anesthetic: amides or esters; so the other class may be dosed during procedures. Dosing recommendations will follow later in this chapter.

Monitoring and Room Set-Up

According to Medicare guidelines:

The provider who monitors the patient should have training and understanding of the agents that are administered and they should be readily available. Emergency equipment should be available as listed on example III from ASA guidelines.4 Most outpatient surgery centers require on-site staff with ACLS certification and/or physicians trained in anesthesiology or emergency medicine who can manage airway emergencies (Table 4-5).

| Appropriate emergency equipment should be available whenever sedative or analgesic drugs capable of causing cardiorespiratory depression are administered. The lists below should be used as a guide, which should be modified depending on the individual practice circumstances. Items in brackets are recommended when infants or children are sedated. |

From American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology 2002;96:1004-1017.

Nonpharmacologic Management of Procedural Pain

Two main nonpharmacologic techniques have been used to reduce procedural pain: acupuncture and cognitive behavioral strategies. A recent metaanalysis review on acupuncture suggests that there is a small analgesic effect across multiple pain studies, including headache, low back pain, and postoperative pain, and it is difficult to separate whether the pain relief is independent of the psychological impact of the ritual treatment.9 The cognitive strategies of distraction and hypnosis in the treatment of procedural pain in children are clearly effective.10 It seems likely that distraction and other cognitive techniques can help with adult procedural pain as well.

Common Side-Effects and Complaints

Adjuvants: Particularly Antiemetics

Patient satisfaction is clearly an important aspect of any pain procedure. One study by Dr. Macario and others sought to survey what clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid from a patient’s perspective.11 Of the patients, 24% ranked vomiting as their least desirable outcome with avoiding nausea also having high importance. The main way of avoiding nausea for interventional pain procedures is to limit the amount of opioids, such as fentanyl, for analgesia.

An expert consensus was published by Dr. Gan and colleagues in 200312 for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. If a patient has received no prophylaxis, 5-HT3 receptor therapy is recommended, which includes ondansetron 1.0 mg, dolasetron 12.5 mg, granisetron 0.1mg, and tropisetron 0.5 mg. The panel agreed that there is no evidence of any difference in the efficacy and safety profiles of the serotonin receptor antagonists. Other alternative therapies for rescue include: droperidol 0.625 mg IV, dexamethasone 2 to 4 mg IV, and promethazine 12.5 mg IV. Of note, droperidol has a black box warning for QT prolongation and torsades de pointes as well as neuroleptic effects (Table 4-6).

| Initial Therapy | Failed Prophylaxis |

|---|---|

| No prophylaxis or dexamethasone 5-HT3 antagonist∗ plus second agent† Triple therapy with 5-HT3 antagonist∗ plus two other agents† when PONV occurs <6 hr after surgery (V) Triple therapy with 5-HT3 antagonist∗ plus two other agents† when PONV occurs >6 hr after surgery (V) |

Administer small-dose 5-HT3 antagonist∗ (IIA) Use drug from different class (V) Do not repeat initial therapy (IIIA) Use drug from different class (V) or propofol, 20 mg as needed in postanesthesia care unit (adults) (IIIB) Repeat 5-HT3 antagonist∗ and droperidol (not dexamethasone or transdermal scopolamine) Use drug from different class (V) |

5-HT3 = serotonin.

∗ Small-dose 5-HT antagonist dosing: ondansetron 1.0 mg, dolasetron 12.5 mg, granisetron 0.1 mg, and tropisetron 0.5 mg.

† Alternative therapies for rescue: droperidol 0.625 mg IV, dexamethasone 2-4 mg IV, and promethazine 12.5 mg IV.

From Gan TJ, Meyer T, Apfel CC, et al: Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 2003;97:62-71.

If a patient is known to have high risk for postoperative nausea and vomiting, dexamethasone 4 mg IV preoperatively can be highly effective both from an efficacy and cost perspective.13 One question is whether a single dose of dexamethasone IV can affect the interpretation of whether the interventional procedure has changed the patient’s pain scores. Even doses of up to 8 mg of dexamethasone preoperatively has no effect on pain and mobilization scores after colorectal surgery.14 Dexamethasone 8 mg can elevate postprocedural glucose concentrations in patients with impaired glucose tolerance and may not be the best first-line choice for nausea prophylaxis, especially if the patient is receiving steroids for the interventional block as well.

Medications

Sedatives and Amnestics

The main goal of intravenous sedation is to provide a short duration anxiolytic and amnestic that is controlled so that airway compromise is avoided. In general, benzodiazepines are used as first line agents. Benzodiazepines induce sedation and anxiolysis by modulating GABA transmission in the CNS. GABA is one of the most common inhibitory neurotransmitters in the brain and benzodiazepines bind to GABAA receptors, increase chloride ion channel influx, and subsequently decrease neuronal excitation.15 Midazolam (Versed) is usually the most preferred benzodiazepine administered compared to lorazepam (Ativan) or diazepam (Valium) because of the shorter elimination half-life (approximately 2 hours for midazolam compared to 12 hours for lorazepam, and 20 to 50 hours for diazepam).16 Typical intermittent dosages of midazolam range from 0.5 mg to 1 mg repeated, lorazepam 0.25 mg repeated, and diazepam 1 to 2 mg repeated. Habitual alcohol usage increases the clearance of midazolam so higher dosages may be required for sedation. Lorazepam is less affected by enzyme induction and other factors that alter cytochrome P450 metabolism. Age and smoking decrease the metabolism of diazepam and can prolong sedative effects. Diazepam may be used if the patient is already taking that agent as an antispasmotic or muscle relaxant or if it is used as an anxiolytic orally many hours prior to the procedure. Midazolam is probably the preferred choice for short interventional procedures, especially if the patient is not taking chronic benzodiazepines as anxiolytics.

Flumazenil is a benzodiazepine antagonist that is similar to midazolam in structure. It reverses benzodiazepine overdosage or oversedation in a dose-dependent manner. Although it is the primary benzodiazepine reversal agent available, compared with benzodiazepine antagonists (midazolam, lorazepam, diazepam), it has the highest clearance and shortest elimination half-life—approximately 1 hour.16 Hence, flumazenil will provide rapid onset of reversal but will require continued monitoring for resedation and even a continuous intravenous infusion to outlast the original benzodiazepine agonist. Flumazenil may be dosed at 0.1 to 0.2 mg every 1 to 2 minutes to a maximum of 1.0 mg. Practitioners should note that flumazenil will reverse any lowering of seizure threshold that the initial benzodiazepine dosage may have induced.

Deeper Sedation

Etomidate is an anesthetic induction drug that has a similar affect to benzodiazepines by increasing the number of GABA receptors and, thereby increasing GABA inhibition.15 The duration of a single dosage lasts approximately 5 minutes at standard induction dosages (0.3 mg/kg or about 20 to 40 mg) and is rapidly metabolized in the liver.17 In anesthesia, the main advantage of etomidate is that it does not produce cardiac hypotension when compared with other induction agents such as propofol. A single dose of etomidate can cause adrenocortical suppression18 as well as myoclonic activity. A single dosage of etomidate at 10 mg is used for cardioversion procedures in adults.

Propofol has revolutionalized outpatient surgical procedures with its rapid onset, short duration of action, and quick recovery for patients.19 It has a chemical structure that is unrelated to other sedative hypnotic compounds18 but does affect GABA-mediated transmission. It has amnestic properties but they are not as marked as the benzodiazepines. Of note, propofol is a cardiovascular depressant and can be associated with respiratory depression at anesthetic induction doses (2 to 2.5 mg/kg or approximately 140 to 175 mg). Propofol is also extensively metabolized and excreted in the urine (>88%).

There is an additive and synergistic hypnotic effect with propofol and other amnestics. So even when titrating propofol at 2.5 to 5 mg increments every few minutes after a base of midazolam and fentanyl, oversedation and respiratory compromise can occur. In addition, cognitive impairment can occur even after short procedures such as outpatient colonoscopy.20 Administration of >2 mg of midazolam was a predictor of impaired cognitive function at discharge. Typically, propofol seems to be used with interventional pain procedures that have become extended or problematic, often when moderate dosages of midazolam and/or fentanyl have been given.

Ketamine is one of the oldest anesthetics (>30 years) that provides moderate sedation and analgesia in one compound. It does not suppress pharyngeal and laryngeal reflexes and can be administered in nonoperating room conditions by nonanesthesiologists.21 Ketamine produces a “dissociative” anesthetic state, which is characterized as a state of catalepsy in which the eyes remain open with a slow nystagmic gaze while corneal and light reflexes remain intact.22 The chemical structure is similar to phencyclidine (PCP) so one of the main side-effects is psychotomimetic experiences or “weird trips.”23

Ketamine’s mechanism of action is at NMDA receptors as well as cholinergic receptors of the muscarinic type and brain acetylcholinesterase. Potentiation of GABA inhibition has also been reported with high doses.24 Because of activity at NMDA receptors, ketamine could theoretically be more effective in treating neuropathic pain states or patients who are opioid tolerant.25 Current evidence does not support routine use of ketamine for treatment of chronic pain.23

As an adjunct to outpatient interventional pain procedures, a dosage of 0.5 to 2 mg/kg (approximately 30 to 140 mg) can be administered as an induction bolus. One of the author’s recommendations would be to dose 20 to 30 mg IV bolus at one time and observe the effect, particularly if the patient has already received other sedative and analgesic agents. Ketamine undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism by the cytochrome P-450 system. It may produce hyperreactive airway reflexes, especially in the presence of inflammation of the upper respiratory tract22 and can give rise to myoclonic jerks or involuntary movements.26

Opioid Analgesics

Opioid analgesic agents are the first-line medications for the relief of acute pain.27 Although morphine, the gold standard, and meperidine have been available for many years, their slower onset >10 minutes and prolonged duration of 1 to 2 hours have steered most interventional pain physicians to use the short-acting fentanyl family of synthetic opioids for procedural analgesia. All opioids act at mu receptors at the spinal cord and supraspinal levels causing a decrease in nociceptive input at the spinal lamina and activation of descending inhibitory control centers of the periaqueductal grey.

Remifentanil is the most lipid-soluble opioid in the fentanyl family and can provide analgesia only by continuous infusion due to ultrahigh clearance by esterases in the blood and tissues. This agent probably does not have a use in standard interventional pain procedures particularly because of the possibility of increasing postoperative pain.28

Morphine and meperidine may be used sparingly in the postoperative setting. Titrating morphine at 2 to 4 mg intravenously every 10 minutes can provide additional pain relief for opioid-tolerant patients for a duration of 2 to 4 hours or the duration of most patient’s travel home. Nausea and urinary retention rates are higher with morphine than with fentanyl. Meperidine is a weak opioid agonist that has been used for treatment of postoperative shivers at 25 mg IV. Because higher doses (700 mg) can produce seizures from normeperidine accumulation making interpretation of local anesthetic toxicity difficult, the authors recommend not using more than 25 to 50 mg IV for perioperative shivering.

A Brief Word on Local Anesthetics

2-chloroprocaine is a rapid onset local anesthetic similar to lidocaine. It works within 5 minutes and has a duration of 30 to 60 minutes. It is the most rapidly metabolized local anesthetic in use. Prior concerns existed over reports of spinal toxicity when administered into the epidural space. New formulations have had the prior ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) removed, which may have caused paraspinal spasms in the past.27 Chloroprocaine may not be used if the patient reports an allergy to suntan lotion that contains benzocaine, a topical ester local anesthetic.

Postprocedural Care and Monitoring

The ASA has provided thorough recommendations for recovery and discharge criteria after sedation and analgesia (Table 4-7). In general, recovery room providers must be able to assess and manage procedural complications, such as respiratory distress, seizure, neurologic events, and cognitive changes. In particular, many outpatient surgery centers are requiring physicians and other staff to have ACLS credentialing particularly if anesthesiologists or emergency medicine specialists with airway management training are not available on site.

Table 4-7 Recovery and Discharge Criteria after Sedation and Analgesia

From American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-1017.

1. Green S.M., Krauss B. Procedural sedation terminology: Moving beyond “conscious sedation”. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:433-435.

2. Gross J.B., Bailey P.L., Caplan R.A., et al. Practice Guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists: A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:459-471.

3. Smith I., Taylor E. Monitored Anesthesia Care. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1994;32:99-112.

4. American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for sedation and analgesia by non-anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1004-1017.

5. Innes G., Murphy M., Nijssen-Jordan C., et al. Procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Canadian Consensus Guidelines. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:145-156.

6. Martin M.L., Lennox P.H. Sedation and analgesia in the interventional radiology department. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:1119-1128.

7. Cohen M.M., Duncan P.G., Tate R.B. Does anesthesia contribute to operative mortality? JAMA. 1988;260:2859-2863.

8. Dailey P.A. Chlorhexidine or Povidone-Iodine. CSA Bulletin, 58. 2009:45-47. http://www.csahq.org/pdf/bulletin/chlorhex_58_3.pdf. Accessed Nov 22, 2009

9. Madsen M.V., Gotzsche P.C., Hrobjartsson A. Acupuncture treatment for pain: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and no acupuncture groups. BMJ. 2009;338:a3115.

10. Stinson J., Yamada J., Dickson A., et al. Review of systematic reviews on acute procedural pain in children in the hospital setting. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:51-57.

11. Macario A., Weinger M., Carney S., Kim A. Which clinical anesthesia outcomes are important to avoid? The perspective of patients. Anesth Analg. 1999;89:652-658.

12. Gan T.J., Meyer T., Apfel C.C., et al. Consensus guidelines for managing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:62-71.

13. Apfel C.C., Korttila K., Abdalla M., et al. A factorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441-2451.

14. Kirdak T., Yilmazlar A., Cavun S., et al. Does single, low-dose preoperative dexamethasone improve outcomes after colorectal surgery based on an enhanced recovery protocol? Double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Am Surg. 2008;74(2):160-167.

15. Barash P.G. Clinical Anesthesia. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1993, p 388

16. Miller’s Anesthesia. 1994:249-258.

17. Absalom A., Pledger D., Kong A. Etomidate USP Dispensing Information. Micromedex. 2001;1:1459-1461.

18. Absalom A., Pledger D., Kong A. Adrenocortical function in critically ill patients 24h after a single dose of etomidate. Anaesthesia. 1999;54(9):861-867.

19. White P.F. Propofol: Its role in changing the practice of anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:1132-1136.

20. Padmanabhan U., Leslie K., Eer A.S., et al. Early cognitive impairment after sedation for colonoscopy: The effect of adding midazolam and/or fentanyl to propofol. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1448-1455.

21. Sobel R.M., Morgan B.W., Murphy M. Ketamine in the ED: Medical politics versus patient care. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:722-725.

22. White P.F., Way W.L., Trevor A.J. Ketamine: Its pharmacology and therapeutic uses. Anesthesiology. 1982;56:119-136.

23. Hocking G., Cousins M.J. Ketamine in chronic pain management: An evidence-based review. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1730-1739.

24. Raeder J.C., Stenseth L.B. Ketamine: A new look at an old drug. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2000;13:463-468.

25. Laulin J.P., Maurette P., Corcuff J.B., et al. The role of ketamine in preventing fentanyl-induced hyperalgesia and subsequent acute morphine tolerance. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1263-1269.

26. Ng K.C., Ang S.Y. Sedation with ketamine for paediatric procedures in the emergency department—A review of 500 cases. Singapore Med J. 2002;43:300-304.

27. Raj P.P. Practical Management of Pain, 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2000. 462

28. Guignard B., Bossard A.E., Coste C., et al. Acute opioid tolerance—Intraoperative remifentanil increases postoperative pain and morphine requirement. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:409-417.