Connective tissue

Structural composition

Connective tissue cells

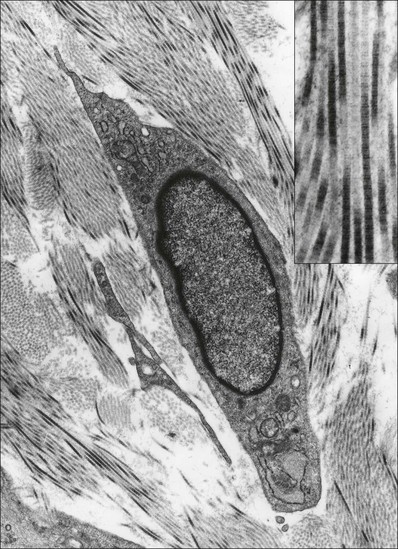

Fibroblasts, the majority of cells in ordinary connective tissue, arise from the relevant undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells1 and are involved in the production of fibrous elements and non-fibrous ground substance (Fig. 3.1). During wound repair they are particularly active and migrate along strands of fibrin by amoeboid movements to distribute themselves through the healing area to start repair. Fibroblast activity is influenced by various factors such as the partial pressure of oxygen, levels of steroid hormones, nutrition and the mechanical stress present in the tissue.2

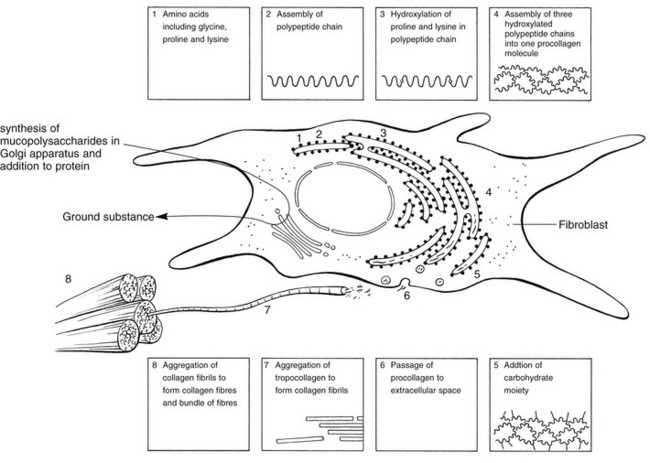

The other cell types are migrant cells and only occasionally present, such as: macrophages, lymphocytes, mast cells, and granulocutes (Table 3.1).3,4

Extracellular matrix (ECM)

The extracellular matrix is composed of insoluble protein fibres, the fibrillar matrix and a mixture of macromolecules, the interfibrillar matrix. The latter consists of adhesive glycoproteins and soluble complexes composed of carbohydrate polymers linked to protein molecules (proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans), which bind water. The extracellular matrix distributes the mechanical stresses on tissues and also provides the structural environment of the cells embedded in it, forming a framework to which they adhere and on which they can move.5

Non-fibrous ground substance

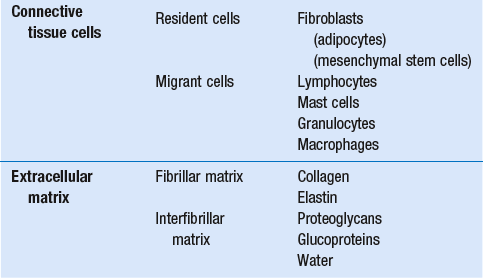

The interfibrillar ground substance is composed of proteoglycans (a family of macromolecules) which bind a high proportion of water (60–70%) and glycoproteins. The latter have a complex shape and are soluble polysaccharide molecules (glycosaminoglycans) bound to a central protein core. In cartilage, the proteoglycans are in turn bound to hyaluronan (a long chain of non-sulphated disaccharides) to form a proteoglycan aggregate – a bottlebrush three-dimensional structure (Fig. 3.2).6 Glycoprotein secures the link between proteoglycan and hyaluronan and also binds the components of ground substance and cells.

Fibrous elements

The fibrous elements are collagen and elastin – both insoluble macromolecular proteins. Collagen is the main structural protein of the body with an organization and type that varies from tissue to tissue. Collagen fibres are commonest in ordinary connective tissue such as fascia, ligament and tendon. The fibrillar forms have great tensile strength but are relatively inelastic and inextensible. By contrast elastin can be extended to 150% of its original length before it ruptures. Elastin fibres return a tissue to its relaxed state after stretch or other considerable deformation. They lose elasticity with age when they tend to calcify. Box 3.1 outlines the components of connective tissue.

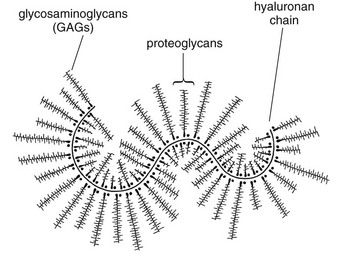

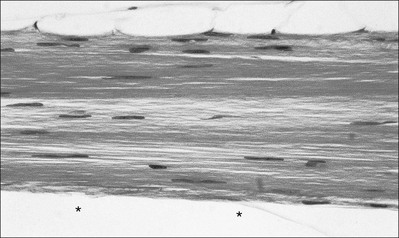

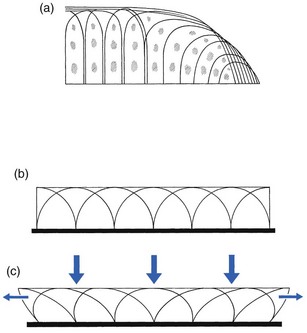

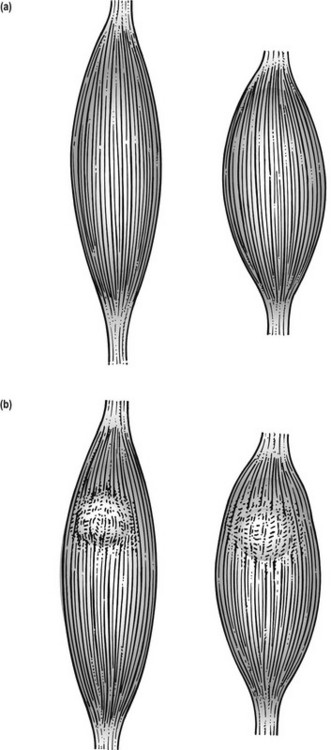

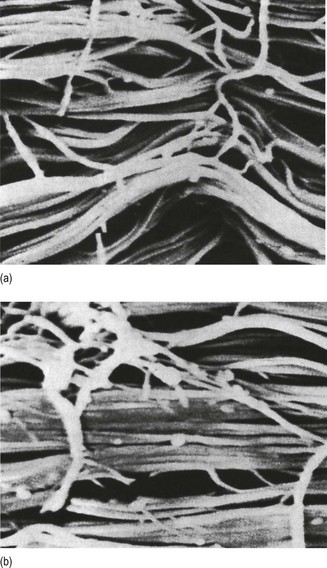

The basic molecule of collagen is procollagen, synthesized in the fibroblast, illustrated in Figure 3.3, steps 1–4. It is formed of three polypeptide chains (α-chains). Each chain is characterized by repeating sequences of three amino acids – glycine, proline and lysine joined together in a triple helix. The helical molecules are secreted into the extracellular space where they slowly polymerize and crosslink (Fig. 3.4). They overlap each other by a quarter of their length, lie parallel in rows and are collected into large insoluble fibrils. The fibrils unite to form fibres, finally making up a bundle. An aggregate of bundles makes up a whole structure such as a ligament or a tendon. The individual bundles are in coils, which increases their structural stability and resilience, and permits a small physiological deformation before placing the tissue under stress, and in consequence permits a more supple transfer of tractive power in the structure itself and at points of insertion (Fig. 3.5). The process of collagen synthesis is stimulated by some hormones (thyroxine, growth hormone and testosterone), although corticosteroids reduce activity.

Fig 3.5 (a) Unloaded collagen fibres in a human knee ligament. (b) Physiological deformation after stress. From Kennedy et al7 with permission (http://jbjs.org/).

• Type I: the most abundant of all collagen. Strong thick fibres packed together in high density. It predominates in bone, tendon, ligament, joint capsule and the annulus fibrosus of the intervertebral disc.

• Type II: thin fibres found in articular cartilage and the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disc. They particularly function in association with a high level of hyaluronan and sulphated proteoglycans to provide a hydrated and pressure-resistant core.

• Type III: essentially present in the initial stages of wound healing and scar tissue formation. It secures early mechanical strength of the newly synthesized matrix. These relatively thin, weak fibres are replaced by the strong type I fibres as healing proceeds.

Regular types

Highly fibrous tissues such as ligaments, tendons, fascia and aponeuroses are predominantly collagenous and show a dense and regular orientation of the fibres with respect to each other. The direction of the fibres is related to the stress they experience. Collagen bundles in ligaments and tendons are very strong and rupture usually takes place at the bony attachments rather than by tearing within their substance (Fig. 3.6).

Innervation

Structural and physiological studies8,9 have shown the presence of at least four types of receptor. Three of these have encapsulated endings but the fourth consists of free unencapsulated endings:

• Type 1 (Ruffini endings) are present in the superficial layers of a fibrous joint capsule. They respond to stretch and pressure within the capsule and are slow adapting with a low threshold. They signal joint position and movement.

• Type 2 are particularly located in the deep layers of the fibrous capsule. They respond to rapid movement, pressure change and vibration but adapt quickly. They have a low threshold and are inactive when the joint is at rest.

• Type 3 are found in ligaments. They transmit information on ligamentous tension so as to prevent excessive stress. Their threshold is relatively high and they adapt slowly. They are not active at rest.

• Type 4 are free unencapsulated nociceptor terminals which ramify within the fibrous capsule, around adjacent fat pads and blood vessels. They are thought to sense excessive joint movements and also to signal pain. They have a high threshold and are slow adapting. Synovial membrane is relatively insensitive to pain because of the absence of these nerve endings.

Structures containing connective tissue

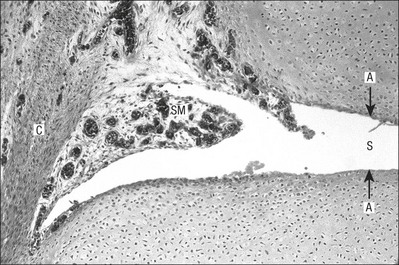

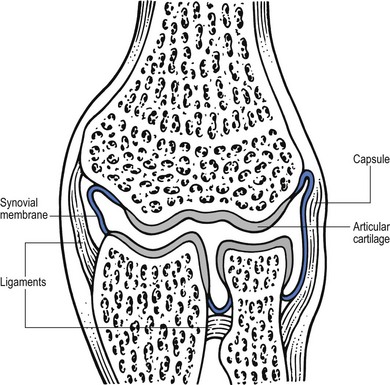

Synovial joints (Fig. 3.7)

Fig 3.7 Example of a synovial joint.

Fibrous capsule and ligaments

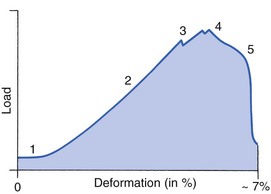

The mechanical response of a ligament to a load can be represented on a load–deformation curve (Fig. 3.8). In the first part of such a curve (its foot) the ground substance is almost completely responsible for absorbing the stress and displaces the fibres in the direction of the stress. When the load is increased, ligamentous tissue responds slowly and maximum resistance to distraction is only possible if there is enough time for realignment of the collagen bundle. The linear part of the curve shows the slow elastic stretching of the collagen. During this stage, recovery of the original shape of the tissue occurs when the deforming load is removed. This slow rate of deformation is known as ‘creep deformation’. Even in this linear part of the curve, breaking of intermolecular crosslinks begins. For this reason it is assumed that, in physiological circumstances, the load on ligaments is kept within that shown in the foot of the curve, where collagen is not yet under undue strain and the role of ground substance is maximal.10 The composition and the amount of gel ground substance are therefore important in load bearing. On reaching the yield point, a non-elastic or plastic deformation occurs and the ligament progressively ruptures. Some investigators have found that in bone–ligament–bone preparations, separation occurs at the point of insertion.11

Fig 3.8 Mechanical response of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee to a load. 1. Foot of the curve, the ground substance alone almost completely absorbs the stress. 2. Linear part of the curve, slow elastic stretching of the collagen which is known as ‘creep deformation’. 3. Yield point, a non-elastic or plastic deformation occurs. 4 and 5, the ligament progressively ruptures. Redrawn from Frankel33 with permission.

Synovial membrane and fluid

The synovial membrane lines the non-articular parts of synovial joints such as the fibrous capsule and the intra-articular ligaments and tendons within the margins of articular cartilage. The internal surface of the membrane has a few small synovial villi which increase in size and number with age. It also has flexible folds, fringes and fat pads. These accommodate to movement so as to occupy potential spaces and may promote the distribution of synovial fluid over the joint surfaces (Fig. 3.9).

Structurally the membrane consists of a cellular intima which is one to four cells deep that rests upon a loose connective tissue subintima and contains the vascular and lymphatic network which has an important function in the supply and removal of fluid. On ultrastructural examination, two cell types (A and B) are apparent. These are closely involved not only with the production of synovial fluid12 but also in the absorption and removal of debris from the joint cavity. The A cells especially have marked phagocytic potential.13 Some synovial cells can also stimulate the immune response by presenting antigens to lymphocytes if foreign material threatens the joint cavity.14

Synovial fluid is a clear, viscid (glairy) substance formed as a dialysate containing some protein. It occurs not only in synovial joints but also in bursae and tendon sheaths. Secretion and absorption are functions of the cells of the intima and of the vascular and lymphatic plexus in the subintima. The synovial initima cells also secrete hyaluronan molecules into the fluid and much evidence has accumulated to show that the viscoelastic and plastic properties of the fluid are largely determined by its hyaluronan content. Chains of hyaluronan bind proteins; these complexes are negatively charged and in turn bind water. The biophysical process is similar to that of the proteoglycans in the matrix of connective tissue and a thick viscous liquid which resembles egg white is formed. Its viscosity varies widely according to circumstances. With a low rate of shear, water is driven out of the hyaluronan–protein complexes and the fluid becomes highly viscous; increase in shear lowers viscosity and the fluid tends to behave more like water. In contrast to viscosity, elasticity increases with higher rates of shear. Both viscosity and elasticity decrease with increasing pH and temperature.15

Cartilage

Articular cartilage is essentially a specialized type of connective tissue.

Composition

Cartilage cells or chondrocytes occupy small spaces in the matrix

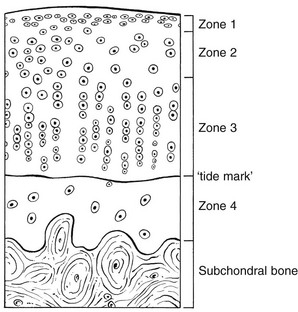

Chondrocytes change with increasing depth from the surface1,16 (Fig. 3.10). In the superficial stratum (zone 1), cells are small, flattened and disposed parallel to the surface. They are surrounded by fine tangentially arranged collagen fibres. A thin superficial layer of this zone has been shown to be cell-free. Cell metabolism in this part is low, which is consistent with the absence of wear and tear in normal healthy tissue. The cells of the intermediate stratum (zone 2) are larger and more rounded and those in the radiate stratum (zone 3) are large, rounded and arranged in columns perpendicular to the surface. In these deeper zones, cells are screened from the coarse fibres by a coat of pericellular matrix bordered by a network of fine collagen fibres. In this way, cells are protected against the stresses generated by load conditions.

The collagen fibres vary in structure and position with increasing depth from the surface (Fig. 3.11a)

In the intermediate stratum, collagen fibres are coarser and more spread out to pursue an oblique course that forms a three-dimensional network. In non-load conditions the fibres are orientated at random but when load is applied they are immediately stretched in a direction perpendicular to that of the applied force (Fig. 3.11c). When the load is removed the fibres return to their original oblique position. This behaviour partly explains the resilience and elasticity of cartilagenous tissue.

Characteristics of cartilage

Articular cartilage lacks a nerve supply and is also completely avascular. Nutrition is derived from three sources: synovial fluid, vessels of the synovial membrane and vessels in the underlying marrow cavity which penetrate the deepest part of the cartilage over a short distance. This last source is available only during growth because, after growth is completed, the matrix at the deepest part of the cartilage becomes impregnated with hydroxyapatite crystals which form a zone of calcified cartilage impenetrable by blood or lymph vessels (Fig. 3.10, zone 4).

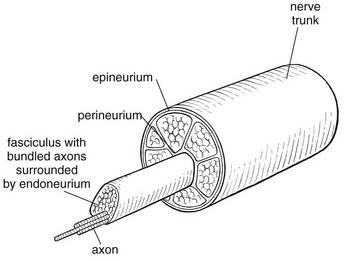

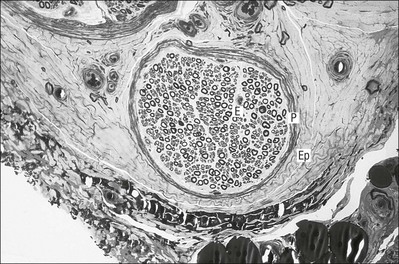

Nerves

Peripheral nerves also possess supporting connective tissue. Within the nerve trunk the efferent and afferent axons are grouped together in a number of fasciculi (Fig. 3.12). The bundled axons in the fasciculi lie roughly parallel, surrounded by loose delicate collagen fibres running longitudinally along them. Both structures show a wavy appearance which disappears when gentle traction is applied.

Each fasciculus is surrounded by a fibrous perineurium, a regular structure of flattened laminae of fibroblasts alternating with fine collagen, running in various directions. These fibroblasts are connected together and form a diffusion barrier against noxious chemical products, bacteria and viruses. In this way, the enclosed axons are to some extent isolated from the external environment. Inside this perineural tube a protein-poor liquid flows centrifugally. This axoplasma is cerebrospinal fluid, which is re-assimilated into the blood circulation at the end of the peripheral nerve. In this respect, the spinal canal and the endoneural spaces are continuous (Fig. 3.13).

The epineurium encases the nerve trunk as a collagen coat with little regular organization. Connective tissue surrounding nerves serves as an important mechanical protection to maintain the conductile properties of the nerve.17 During movement, nerves are potentially exposed to tensile forces that can be avoided by mobility in relation to surrounding structures. Here, the wavy form of both axons and surrounding collagen fibres is an important consideration: this ‘waviness’ of the axons is paramount, allowing them to remain relaxed even when the collagen fibres are stretched. Thus, within the normal range of movement, the axons will be protected by the tensile force of the collagen component. When there is a severe sprain or fracture perhaps with dislocation, the range of plastic deformation of collagen can be exceeded and ultimately rupture of collagen fibres and neurotmesis results.

The tolerance of nerves to tension is much greater than it is to compression. However, the mobility of nerves allows them to move laterally, so avoiding a compressive force. When space is inadequate for such movement or the nerve is firmly anchored – which is the case in cervical nerve roots – the epineurium may absorb a certain amount of pressure but sooner or later the blood supply within the nerve is affected by increasing compression. Further compression may result in interference with the conductile properties of the nerve. In such circumstances, the Schwann cells and subsequently the myelinated sheath are damaged. Although the axons remain intact, action potentials become blocked, leading to loss of sensory and motor function (see Ch. 2).

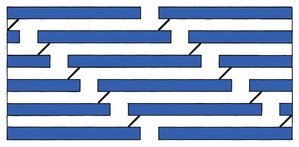

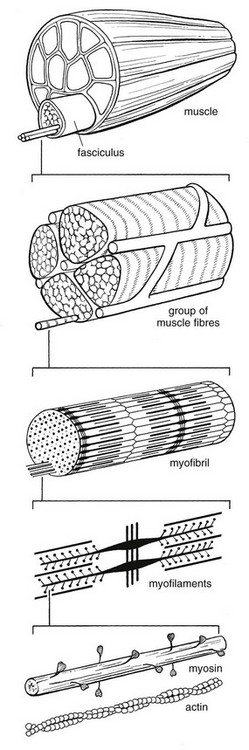

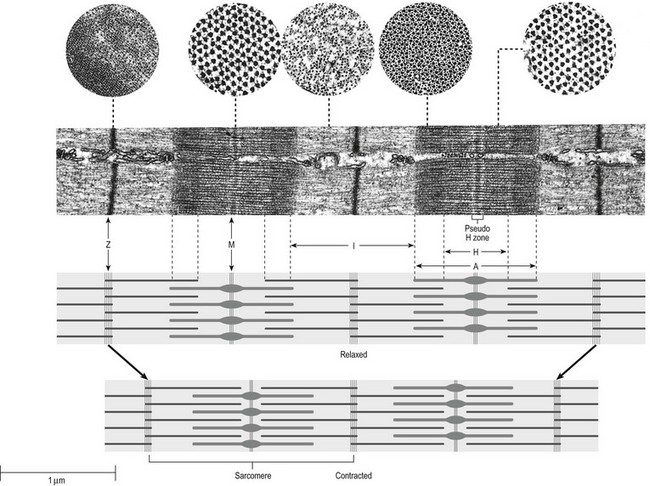

Muscles

The muscle cell or myofibril consists of sarcomeres or myofilaments – the basic contractile units of a muscle – arranged in parallel (Fig. 3.14). In each sarcomere two types of filament are distinguishable, chemically characterized as actin and myosin. The actin filaments are each attached at one end to the inner side of the cell membrane forming the so-called Z-line. At the other end they are free and interdigitate with the central myosin filaments. During muscle contraction, the actin filaments slide in relation to the myosin towards the centre of the sarcomere which brings the attachments at the Z-lines closer together with shortening of the whole contractile unit (Fig. 3.15).

Finally, the whole muscle is surrounded by the stout epimysium, which is continuous with the septa of the outer perimysium and blends with the connective tissue that forms the tendon, fascia or aponeurosis (Fig. 3.16).

Tendons

These structures are largely composed of collagen fibres with a low amount of proteoglycans. On a dry weight basis, collagen represents 60–80% of the total weight of tendon.18

At the surface, the epitendineum or tendon sheath consists of irregularly arranged condensed collagen as well as elastin fibres. It is continuous with the loosely arranged connective tissue that permeates the tendon between its fascicles and provides a route of ingress and egress for vessels and nerves. At the insertion, the collagen bundles of the tendon permeate into bone. It has been shown19,20,21 that the insertion of the connective tissue of ligaments into bone involves a transition from non-mineralized through mineralized fibrocartilage to bone.

In young growing tendons, fibril diameter and tensile strength can be increased by exercise. In adults, however, the effect is minimal although regularly applied tension is necessary to maintain structural integrity. Immobilization has demonstrated loss of tensile strength (see p. 46).

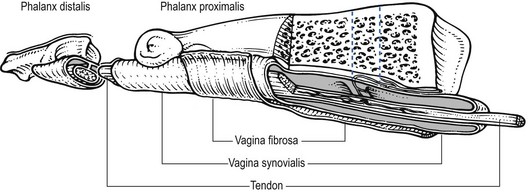

Where tendons pass under ligaments or through osteofibrous tunnels, synovial sheaths are formed which separate the tendon completely from its surroundings. These synovial sheaths have two concentric layers, separated by a thin film of synovial fluid and form a closed double-walled cylinder (Fig. 3.17). The fluid acts as a lubricant and ensures easy mobility of the tendon. The internal (visceral) layer is attached to the tendon and the external (parietal) layer to neighbouring structures such as periosteum and retinaculum.

Trauma to soft connective tissue

Introduction

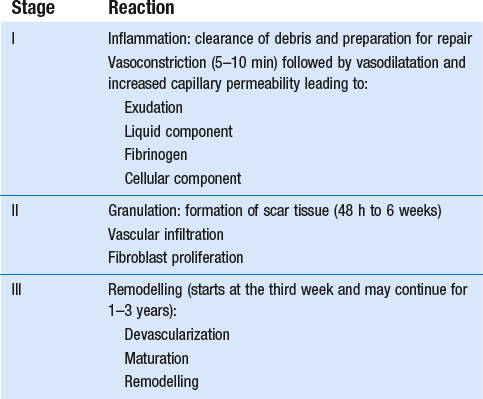

Soft tissue injury involves damage to the structural elements of connective tissue with rupture of arterioles and venules. A general inflammatory reaction follows (Table 3.2), one role of which is defensive in that it prompts the subject to restrict activities while recovery takes place.

Regardless of the site of injury and the degree of damage, healing comprises three main phases: inflammation, proliferation (granulation) and remodelling. These events do not occur separately but form a continuum of cell, matrix and vascular changes that begin with the release of inflammatory mediators and end with the remodelling of the repaired tissue. Connective tissue regenerates largely as a consequence of the action of inflammatory cells, vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells and of fibroblasts.22,23

Inflammation

The first reaction is vasoconstriction of small local arterioles that lasts about 5–10 minutes and is followed by active vasodilatation and increased blood flow for 1–3 days. In major injuries with damage to blood vessels, blood escapes to form a haematoma that temporarily fills the injured site. Within the haematoma, fibrin accumulates and platelets bind to collagen fibrils to form a clot that provides the framework for invasion of vascular cells and fibroblasts.24 The vascular changes and further inflammatory reactions are initiated by chemical mediators released from destroyed tissue cells.25,26 Mast cells release heparin (anticoagulant) and histamine (vascular dilator). Plasma cells produce bradykinins and substance P (pain and vasodilatation). Platelets produce serotonin, prostaglandins and growth factors that stimulate migration, proliferation and differentiation of cells.27,28 In addition, mediators cause migration of leukocytes into the injured area and swelling of the endothelial cells that line vascular channels. The endothelial cells pull away from their attachment to each other to leave sizeable gaps between cells that increase the permeability of vessels and so allow plasma, cells and proteins to escape. As a result, the presence of these proteins enhances the flow by osmosis of more plasma into the injured extracellular space. The whole process is the exudative phase. The liquid part of the plasma exudate dilutes potentially noxious substances and products of cell destruction and helps in their elimination by the supply of globulins and enzymes.

The cellular parts of the exudate are:

• neutrophil granulocytes responsible for phagocytosis and proteolysis of the products of cell destruction

• lymphocytes which increase permeability and help to activate the phagocytosis of damaged cells

• macrophages whose role is probably to engulf and digest protein and to supply amino acids to the fibroblast; macrophages remain present throughout the entire inflammatory phase to assist in the phagocytosis of tissue debris and are also key cells in repair.

Repair

During their proliferation, fibroblasts develop into cells termed myofibroblasts that generate a traction-like activity on the matrix required for the reduction of any gap in the healing area.29

Remodelling

Around the end of the third week maturation begins – the process of reshaping and strengthening the scar tissue by removing, reorganizing and replacing cells and matrix. A better structural orientation and increase in tensile strength result.30 The remodelling phase can be divided into a consolidation and maturation stage:31

• First, vascularization decreases and many of the new vessels atrophy and disappear as the blood supply becomes appropriately adjusted to the needs of the scar tissue.

• Second, the amount, form and strength of scar collagen changes: the immature and weak tissue with a random orientation of fibres in three planes is remodelled into linearly arranged bundles of connective tissue. The process is the result of a number of factors, including turnover of collagen, fibre linkage and increased intermolecular bonding.

It is now generally recognized that internal and external mechanical stress applied to the repair tissue is the main stimulus for remodelling. Tension by gentle movements in functional directions reorientates the collagen and breaks any weak or unnecessary crosslinks that may have formed. Mechanical stress thus has its greatest influence on remodelling at this time. Non-functional collagen is cleared away by phagocytosis.32–36

Remodelling may continue for years although more slowly as time passes. The tensile strength of replaced or repaired collagen in ligaments reaches 50% of normal by 6–25 months after injury and 100% only after 1–3 years.37 The strength of a scar formed in an injured muscle increases faster because of its superior vascular supply.25

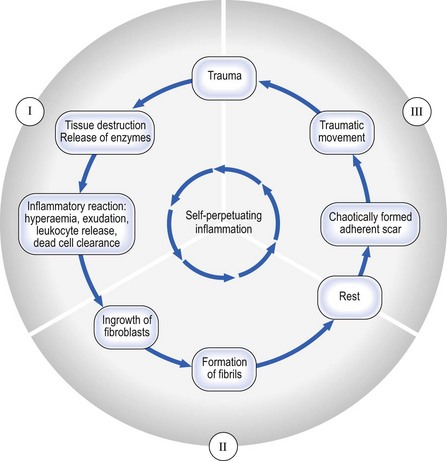

Self-perpetuating inflammation

Cyriax drew attention to such chronic types of inflammation of soft tissues that began as a result of trauma but continued long after the cause had ceased to operate – self-perpetuating inflammation (see Fig. 3.18) – particularly prone to happen after a minor injury to a ligament. Occasionally it also occurs as an overuse phenomenon in a tendon. With knowledge of the inflammatory reaction in traumatized soft tissues, it is clear that lack of movement during the period of repair and remodelling which leads to adhesive scar tissue formation can be responsible for some chronic lesions.

The decision whether a lesion requires rest or movement cannot be taken by the patient, who feels pain and loss of function and interprets these symptoms as a potential threat that can be reduced by immobilization. The main goal in the treatment of musculoskeletal lesions is therefore to guide the healing soft tissues through the stages of inflammation and repair by the provision of sufficient and appropriate motion that can restore painless function. If a chronic self-perpetuating inflammation has become established, a local infiltration of corticosteroid may interrupt the process. The scar becomes painless and the tissue, no longer deprived of its functional motion and appropriate stress, starts to remodel. Another approach which helps to reduce the amount of disorganized scar tissue is to perform deep transverse friction followed by manipulation (see p. 54).

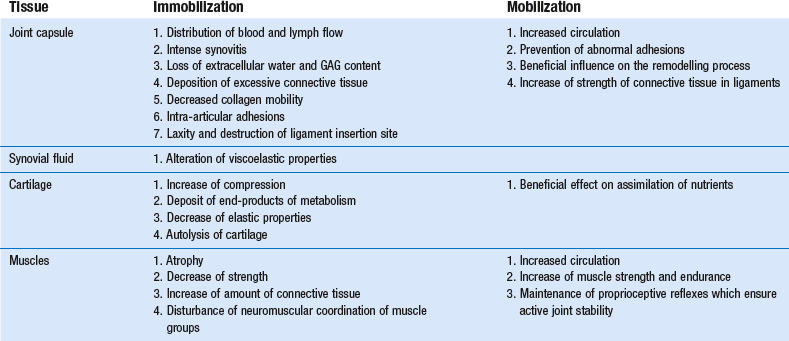

Effects of immobilization on healing

Joint capsule and ligaments

Disturbance of the blood and lymph stream in the synovial membrane influences the supply of nutrients and the scavenging of metabolic products and destroyed cells. Joint immobilization reduces synovial fluid hyaluronan concentration and is accompanied by changes in the synovial intimal cell populations.38

In a study on the effects of immobilization of knee joints of dogs, deposition of excessive connective tissue was noted.39 In the course of time, mature scar and intra-articular adhesions were found which restricted joint motion. Within the matrix a 4.4% loss of extracellular water and a significant reduction in GAG content (30–40%) was established. Ingrowth of new capillaries at the edge of injured tissue was diminished. Other workers studied the effects of immobilization on the knee joint of the rabbit.40,41 They confirmed the findings in the dog but also postulated that loss of water and GAG content would decrease the space between collagen fibres and thus restrict normal interfibre movement. Random orientation of newly generated fibrils and the formation of crosslinks between newly regenerated fibrils and pre-existing collagen fibres were other findings responsible for decreased collagen mobility and restricted movements. These matrix changes are relatively uniform in ligament, capsule, tendon or fascia. Some specific studies on collateral and cruciate ligaments have demonstrated laxity, destruction of ligament insertion site and failure at a lower load after immobilization for 3 months.42–44

Cartilage

Several authors have also demonstrated the deleterious effects of immobilization on cartilage:44–51

• Shortening and thickening of fibrous articular capsule gives rise to a three-fold increase of the compression of articular cartilage, which may eventually initiate degenerative changes in the joint.

• Loss of water content and GAGs in cartilage decreases its elastic properties.

• Decreased capsular blood supply leads to a deposit of some end-products of metabolism at the joint surface.

• Lysosomal enzymes released from dead chondrocytes lead to an autolysis of cartilage which is proportional to the time of immobilization.

Muscle

Muscular reactions to immobilization have also been investigated.52,53 There is:

• decreased capillary density and muscle atrophy

• decrease in muscle strength most dramatically during the first week of immobilization. After 2 weeks in a plaster cast, there is 20% loss of maximum strength. Slow muscle fibres, with predominantly oxidative metabolism, are more susceptible to immobilization atrophy than are fast fibres

• an increased amount of connective tissue. Proliferation first takes place in the perimysial spaces, followed sometimes by the endomysial spaces. It is suggested53 that this may impair the vascular supply of muscle fibres and could facilitate degeneration and also could make regeneration more difficult. Although muscle structure, metabolism and function are severely impaired after immobilization, almost complete recovery is possible provided that the training programme starts with very moderate exercises and avoids maximum voluntary efforts of regenerating muscle fibres

• disturbance of neuromuscular coordination of muscle groups.

Effects of mobilization on healing

The benefit of early mobilization in most soft tissue lesions was advocated by Hippocrates more than 2400 years ago. Capsular circulation is increased (Table 3.3) which aids the supply of nutrients and elimination of cartilagenous debris. Physical joint movements have a beneficial effect on the assimilation of nutrients by the cartilage.54

Experimental findings11,55,56 on the influence of physical activity on ligaments and tendons support the view that the strength of connective tissue is increased with exercise training and decreased with immobilization, provided that the exercise programme is of an endurance nature. Trained animals have significantly heavier ligaments, stronger ligament–bone junctions and junction strength to body weight ratios. Similar effects pertain in repaired ligaments,42,57 which show significantly higher strength values after repair is complete if they have not been immobilized. Early mobilization also considerably influences the remodelling process and prevents formation of abnormal adhesions that may restrict joint movements.58

Another advantage of early mobilization is the positive effect on skeletal muscles,57,59,60 with increased circulation, muscle strength and endurance and maintenance of proprioceptive reflexes, which ensure the active stability of the joint.

Treatment of traumatic soft connective tissue lesions

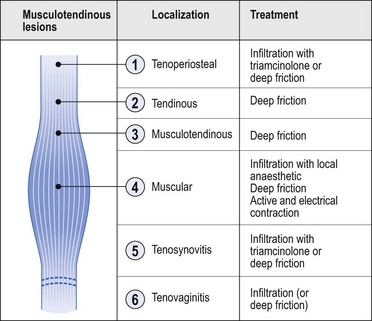

Muscular lesions

Delayed muscle soreness

A delayed, specific soreness sometimes appearing 12–24 hours after intense exercise is well known in athletics and may be caused by the disturbance of metabolism, with a high concentration of lactic acid and the resulting inflammatory reactions: vasodilation, increased capillary permeability and intercellular oedema. Swelling and oxygen deficiency may irritate free nerve endings and lead to muscle spasm.61 Another, more recent, theory is that there is injury to sarcomeres and intramuscular collagen fibres and, in consequence, an inflammatory reaction.62

Minor muscular tears (or ‘muscle strain injuries’)

Acute lesions

These are the common ‘muscle pull’ or ‘strain’ injuries that result from sudden and over-violent effort or movement in the muscle and usually cause immediate disability. Tears occur most often during unusual contractions,63 which produce significantly higher muscle force than when the muscle is held at the same length or is allowed to shorten. It has also been shown that muscles crossing two joints, such as hamstrings and gastrocnemii, are particularly at risk. The vulnerable site appears to be near the muscle–tendon junction. The immediate response to the trauma is inflammation, associated oedema and localized haemorrhage. Excessive oedema and haemorrhage should be reduced as much as possible. Blood collections are not confined to the muscle proper but escape through the perimysium and fascia into the subcutaneous space. As a rule, the degree of pain is consistent with the extent of the rupture.

Treatment

The immediate induction of local anaesthesia at the site of the lesion effectively blocks the nociceptive impulses which are responsible for muscle spasm at the site of damage. Cold therapy as an alternative has been criticized.64 Although it has a positive effect on pain threshold,65,66 physiological effects and procedures of application are still chiefly based on empirical and clinical findings. Van Wingerden suggests that cold therapy, especially when applied in the acute phase of injury, could lead to increased oedema, inhibition of the healing process and even to increased inflammatory reactions.64

From the next day on, active or electrical contractions follow, with the muscle in a fully shortened position to maintain mobility by broadening the muscle belly. Meshwork of regenerating fibrils in the healing breach may hinder the broadening capacity of the muscle fibres during contraction. In the later stages of healing (granulation and remodelling), intramuscular formation of abnormal crosslinks takes place and the inappropriate scar tissue will form a mechanical barrier to broadening during contraction, a chief muscle function (Fig. 3.19).

Deep transverse friction also imitates broadening and prevents newly formed bonds from matting muscle fibres together. It should be started the day after injury, as it can be expected that repair has begun by this time. A gentle type of massage is performed daily for a short period of time (see Ch. 5). At this stage, it should not be done to an extent that interferes with the capillaries and fibrils consolidating themselves in the healing breach. Both intensive passive stretching and resisted movements may cause damage at the site of injury and must be avoided until recovery is well established. It has been demonstrated67,68 that contractile ability recovers rapidly.

Once the patient is free from pain and has a full range of mobility, repetitive stretching exercises seem to make an important contribution to the future prevention of these injuries.69–72 Return to sport can be allowed when the strength of the injured limb has been restored to within 10% of that of the unaffected limb (usually after 3–6 weeks).73

Chronic lesions

Treatment

Steroids do not have a place in the treatment of muscular lesions. Recent research in an animal model indicates that corticosteroids may be beneficial in the short term but they cause irreversible damage to healing muscle in the long term, including disordered fibre structure and a marked diminution in force-generating capacity.74

Myosynovitis

Myosynovitis is a painful condition described by Cyriax,75 arising from a muscle as the result of overuse. In severe cases it is accompanied by crepitus on movement. This uncommon condition seems to occur only in the bellies of the long abductor and the extensor muscles of the thumb and in the musculotendinous junction of the tibialis anterior. The last disorder is a well-known complaint in new military recruits who march unaccustomed distances.

Myositis ossificans

There is the following triad of symptoms:

• Palpable and increasing firm mass in the affected muscle

• Gradual decrease in the range of movement of the neighbouring joint(s).76,77

The history of severe contusion to the affected muscle is helpful in the early evaluation of these patients because radiographic changes become evident only 2–4 weeks following the trauma. The condition can mimic benign or malignant bone tumour and osteomyelitis.78,79

Specific treatment is not recommended. Bone formation may resorb with time but recovery may take from 1 to 2 years. Early surgery is to be avoided because it may exacerbate the bone formation. Removal can be considered if symptoms persist, but only after the heterotopic bone is mature and no further radiological changes occur.80,81

Tendinous lesions

Terminology

Within the literature, there is much confusion about the terminology and over the last decades, numerous terms have been used to describe the pathology of tendons. The most common term is ‘tendinitis’ which focuses on clinical inflammatory signs. Puddu et al.82 proposed the term tendinosis as a histological description of a degenerative pathology with a lack of inflammatory change. As these terms are often used interchangeably and without precision83 it may be more appropriate to refer to a symptomatic primary tendon disorder as a tendinopathy as this makes no assumption as to the underlying pathological process.84

‘Tendinitis’

When strain on a tendon tears some fibres, it always seems to occur in those parts of the tendon where vascularization is relatively poor. The insertion into bone and sometimes a specific part of a tendon are such ‘critical’ vascularized zones. Good examples are a zone in the Achilles tendon about 2.5 cm above its insertion into the calcaneus85,86 and the supraspinatus tendon close to its insertion on the major tubercle.87

Chronic (overuse) lesions

Treatment

Modalities and effects of this treatment form are discussed in the online chapter Applied anatomy of the cervical spine but transverse friction aims to achieve transverse movement of the collagen structure of the connective tissue. In this way adhesion formation is prevented and existing adhesions are mobilized. The cyclic loading and motion of the healing connective tissues may also stimulate formation and remodelling of the collagen.

Tenosynovitis

Tendinosis

This is a degenerative condition of the tendon without accompanying inflammatory reactions and therefore often without clinical symptoms. The lesion is characterized by visible discolouring of the tissue and loss of the mirror-like gloss of the tendon surface and is typically described as ‘mucoid degeneration’.88

Tendinosis and mucoid degeneration often lead to spontaneous ruptures (long head of the biceps, Achilles tendon). It is suggested that the ‘typical’ histopathological changes characterized by tendon degeneration may not necessarily be directly linked to increased nociception giving the patients warning signals; while in painful ‘tendinitis’ the mechanically weaker tendons may be protected from ruptures due to decreased impact levels since painful activities will be avoided.89

Complete rupture

Complete rupture of a tendon usually results from indirect trauma. It always seems to occur at the midsubstance of the tendon. Acute tears are those occurring suddenly, usually as a result of a single injury. Chronic tears are those that are insidious in onset and result from repetitive loading of a degenerated and weakened tendon (see above). Tendinous ruptures occur predominantly at the shoulder, wrist and heel. At the shoulder, the incidence of full thickness rotator cuff tears in cadaveric populations ranges from 30%90 to 60%.91

Mechanical strength of a healing tendon is related to the histological process of repair. During the second phase, strength increases but is still insufficient to prevent further stretching of the healing wound. For this reason, the region always has to be immobilized until the process of maturation has begun (about 3 weeks after injury). At that time the arrangement of collagen fibrils is not organized and remodelling depends entirely upon the presence of repetitive tensile forces applied to the scar tissue. Several studies support the concept that controlled cyclic passive loading of the healing tendon, performed after the initial healing phase (3 weeks) is effective in decreasing the formation of abnormal adhesions and increasing the tensile strength of the healing tissue.92–94

Ligamentous lesions

Rationale for treatment of acute and chronic lesions

Treatment regimes remain the subject of controversy and range from a policy of no treatment through early mobilization and strapping to plaster immobilization. However, experimental studies of the past decades confirm the existing clinical feeling that sprained ligaments heal better and stronger under functional loading than they do during rest. The effects of loading on healing ligaments have been studied extensively and the available evidence indicates that the remodelling of the repair tissues responds extremely well to cyclic loading and motion.95 Long-term studies in ankle sprains have shown better results when early mobilization is used.96,97 Other prospective and randomized studies also show the best results with early functional treatment (see Cyriax98 p. 8, Larsen99 and Freeman100). Because late reconstruction of ruptured ligaments at the ankle still gives very good results,101–103 there is no need for early surgical treatment and conservative treatment with early mobilization must always be tried first. At the knee joint, several studies have also demonstrated that the non-operative management of an isolated medial collateral ligament rupture gives results equally as good as surgical repair but with significantly quicker rehabilitation.104–109

‘Sprain’ of a ligament is the result of excessive joint movement with lack of muscular control. The transitional zone between mineralized fibrocartilage and bone is the site of most separations between ligaments and bones.11 However, sprain may also occur in the substance of a ligament. A good example of this is the medial collateral ligament at the knee, where tears are often situated in the midportion or just below the joint line adjacent to the tibia. Experiments with strength and failure characteristics of rat medial collateral ligaments110 have shown that this especially results from a large load that is rapidly applied. The failure point is reached before significant elongation can take place. The same load applied more slowly results in failure at the transitional zone between mineralized fibrocartilage and bone, where the connective structure is weakest.

In accordance with the degree of the injury, ligamentous lesions can be divided into three grades:

• Grade 1: a slight overstretching with some micro-tears within the ligamentous structure

• Grade 2: a more severe sprain with partial rupture of the ligament

• Grade 3: the ligament is completely torn across or is avulsed from the bony attachment.

This classification is of importance in relation to treatment.

Treatment

Steroid injections during granulation and repair may lead to fewer fibroblasts, a diminished collagen fibre formation and a weaker scar.111 However, these effects are not seen after a single injection during the acute, inflammation stage.112

Overstretching a ligament often leads to permanent laxity with consequent instability of the joint. Cyriax emphasized the propensity of ligaments not controlled by muscles to develop such permanent laxity and cited the sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, sacroiliac and sacrococcygeal ligaments, the symphysis pubis, the cruciate ligaments at the knee and the inferior tibiofibular ligaments as examples.75 After trauma, reflex muscle spasm is not capable of stabilizing these joints. In intracapsular ligaments (e.g. the cruciate ligaments), unsuccessful repair may also result from the synovial environment, limited fibroblast migration and reduced vascular ingrowth.

In joints controlled by muscles, permanent laxity is much less likely to occur. Reflex muscle spasm efficiently stabilizes the joint. Grade I and II lesions treated on the lines set out will heal adequately. The results of conservative treatment in grade III lesions are also successful in almost all cases but it is essential that the lesion is isolated.106,113 It is then advisable to immobilize the joint partially so as to prevent any unwanted movement taking place during recovery. Lasting instability in these joints can be more or less compensated for by tautness of the muscles and tendons passing over the joint. Strength-building exercises are of great importance and must be on an exact and planned basis. If necessary, strapping or braces may provide added support.

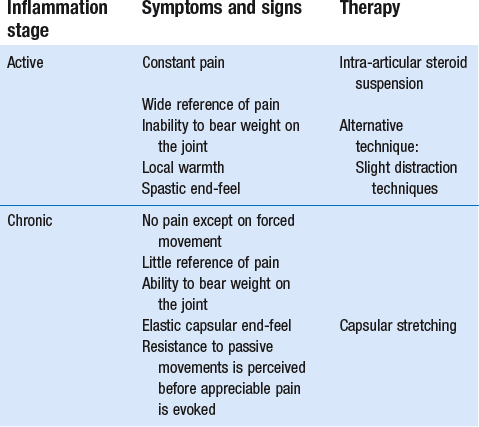

Capsular lesions

After injury, joints supported by muscles soon develop limitation of movement with a capsular pattern (see Ch. 4). In recent arthritis such limitation results from defensive muscle action which is reflexive and controls movements that could further irritate the capsule. Muscles spring into action, which can be felt (hard end-feel) and seen on gently forcing a particular movement.

Treatment (Table 3.4)

Movements retain mobility at a joint. They have the effect of keeping a joint structure normal.98

Forced movements should not be done in traumatic arthritis of the following peripheral joints (see also Box 3.2):

• Elbow: passive mobilization for recent posttraumatic stiffness is apt to diminish rather than increase the range of movement; moreover, it is contraindicated because of the ever-present danger of setting up myositis ossificans. An intra-articular injection with corticosteroid suspension is indicated and will give quick recovery

• Hip: traumatic arthritis is best treated by rest in bed

• Interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints of the hand and foot: these joints respond badly to forced movements. Joints of the toes can be injected with corticosteroid suspension

• Lower radioulnar joint: aggravation of symptoms can be expected even with active exercises.

• Joints not under voluntary control: after an injury the formation of adhesions is not to be expected. Forced movements are useless and harmful. Rest, support and corticosteroid injections are then good alternatives.

Treatment of acute and chronic ligamentous lesions is summarized in Table 3.5.

Table 3.5

Treatment of ligamentous lesions

| Phase | Treatment (1) | Treatment (2) |

| Acute phase | ||

| Joints controlled by muscles | ||

| First day | Compression | Alternative (within 48 hours) |

| Elevation | Steroid infiltration | |

| Following days | Effleurage + | Controlled movements (active and passive) |

| Deep transverse massage | Gait instruction | |

| Controlled movements (active and passive) | ||

| Gait instruction | ||

| Joints not controlled by muscles | Deep transverse massage | Infiltration (steroid or sclerosant) |

| Immobilization | Immobilization | |

| Chronic phase | ||

| Adhesive scar formation | Deep transverse friction + | (Steroid infiltration) |

| Manipulation | ||

| Lasting instability | Strength-building exercises | Surgical reconstruction |

| Proprioceptive training | (Infiltration with sclerosant) |

References

1. Warwick, L, Williams, PL. Gray’s Anatomy, 36th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1980.

2. McAnulty, RJ, Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts: their source, function and role in disease. Int J Biochem & Cell Biol 2007; 39:666–671. ![]()

3. Lewis, CE, McGee, JOD. The Macrophage. Oxford: IRL Press; 1992.

4. Holgate, ST. Mast cells and their mediators. In: Holborrow EJ, Reeves WG, eds. Immunology in Medicine. 2nd ed. London: Academic Press; 1983:979–994.

5. Pollard, TD, Earnshaw, WC. Section VIII, Cell adhesion and the extracellular matrix. In: Cell Biology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

6. Walker, PS. Human Joints and their Artificial Replacements. Springfield: Thomas; 1977.

7. Kennedy, JC, Hawkins, RJ, Willis, RB, Tension studies of human knee ligaments. J Bone Joint Surg 1976; 50A:350–355. ![]()

8. Wyke, B, The neurology of joints. Ann R Coll Surg 1967; 41:25. ![]()

9. Rowinski, M. Afferent neurobiology of the joint. In: Davies GJ, Gould JA, eds. Orthop and Sports: Physical Therapy. St Louis: Mosby; 1985:50.

10. de Morree, JJ. Dynamiek van het menselijk bindweefsel. Functie, beschadiging en herstel. Utrecht/Antwerp: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema; 1989.

11. Tipton, CM, Matthes, RD, Maynard, JA, Carey, RA, The influence of physical activities on ligaments and tendons. Med Sci Sports. 1975;7(3):165. ![]()

12. Henderson, B, Pettipher, ER, The synovial cell: biology and pathobiology. Sem Arthritis Rheum 1985; 15:1–32. ![]()

13. Linck, G, Porte, A. Cytophysiology of the synovial membrane: distinction of two cell types of the intima revealed by their reaction with horseradish peroxidase and iron saccharate in the mouse. Biol Cell. 1981; 42:147–152.

14. Klareskog, L, Forsum, U, Kabelitz, D, et al, Immune functions of human synovial cells. Phenotypic and T cell regulator properties of macrophage-like cells that express HLA-DR. Arthritis Rheum 1982; 25:488–501. ![]()

15. Jay, JD, Characterization of a bovine fluid lubricating factor. I. Chemical, surface activity and lubricating properties. Connect Tissue Res 1992; 28:71–88. ![]()

16. Ghadially, FN. Fine Structure of Synovial Joints. London: Butterworth; 1983.

17. Sunderland, S. Nerves and Nerve Injuries, 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1978.

18. Harkness, RD. Mechanical Properties of Collagenous Tissue. Treatise on Collagen. London: Academic Press; 1968.

19. Cooper, RR, Misol, S, Tendon and ligament insertion: a light and electron microscopy study. J Bone Joint Surg 1970; 52A:1–21. ![]()

20. Laros, GS, Tipton, CM, Cooper, RR, Influence of physical activity on ligament insertions in the knees of dogs. J Bone Joint Surg 1971; 53A:275–286. ![]()

21. Benjamin, M, Toumi, H, Ralphs, JR, et al, Where tendons and ligaments meet bone: attachment sites (‘entheses’) in relation to exercise and/or mechanical load. J Anat 2006; 208:471–490. ![]()

22. Hunt, ThK. Wound healing. In: Dunphy JL, Way LW, eds. Current Surgical Diagnosis and Treatment, chapter 9. Los Altos, California: Lange Medical; 1975:97.

23. Peacock, EE, van Winckle, W. Surgery and Biology of Wound Repairs. Saunders; 1980.

24. Lehto, M, Durance, VC, Restall, D, Collagen and fibronectin in a healing skeletal muscle injury. J Bone Joint Surg 1985; 67B:820–827. ![]()

25. Zarins, B, Soft tissue injury and repair: biomechanical aspects. Int J Sports Med 1982; 3:9. ![]()

26. Kellett, J, Acute soft tissue injuries: A review of the literature. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1986; 18:5. ![]()

27. Banks, AR. The role of growth factor in tissue repair. In: Clark RAF, Henson PM, eds. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Repair. New York: Plenum Press; 1988:2059–2079.

28. Fox, GM. The role of growth factor in tissue repair. In: Clark RAF, Hensoon PM, eds. The Molecular and Cellular Biology of Wound Repair. New York: Plenum Press; 1988:266–272.

29. Ehrlich, HP, Rajaratnam, JBM, Cell locomotion versus cell contraction forces for collagen lattice contraction: an in vitro model for wound contraction. Tissue Cell 1990; 22:407–417. ![]()

30. Buckwalter, JA, Crues, R. Healing of musculoskeletal tissues. In: Rockwood CA, Green DP, eds. Fractures. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1991.

31. Tillman, LJ, Chasan, NP. Properties of dense connective tissue and wound healing. In: Hertling D, Kessler RM, eds. Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1996:8–21.

32. Stearns, ML. Studies on development of connective tissue in transparant chambers in rabbit’s ear. Am J Anat. 1940; 67:55.

33. Frankel, VH, Nordin, M. Basic Biomechanics of the Skeletal System. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1980.

34. McGaw, WT, The effect of tension on collagen remodelling by fibroblasts: a stereological ultrastructural study. Connect Tissue Res 1986; 14:229. ![]()

35. van der Meulen, JCH, Present state of knowledge on processes of healing in collagen structures. Int J Sports Med 1982; 3:4. ![]()

36. Hardy, MA, The biology of scar formation. Phys Ther 1989; 69:1014–1023. ![]()

37. Frank, G, Woo, SL-Y, Amiel, D, et al, Medial collateral ligament healing. A multidisciplinary assessment in rabbits. Am J Sports Med 1983; 11:379. ![]()

38. Pitsillides, AA, Skerry, TM, Edwards, JC, Joint immobilization reduces synovial fluid hyaluronan concentration and is accompanied by changes in the synovial intimal cell populations. Rheumatology. 1999;38(11):1108. ![]()

39. Akeson, WH, Amiel, D, Woo, S, Immobility effects of synovial joints; the pathomechanics of joint contracture. Biocheology 1980; 17:95–110. ![]()

40. Akeson, WH, An experimental study of joint stiffness. J Bone Joint Surg 1961; 43A:1022. ![]()

41. Akeson, WH, Ameil, D, LaViolette, D, The connective tissue response to immobility: an accelerated aging response. Exp Gerontol 1968; 3:329. ![]()

42. Erikson, E, Sports injuries of the knee ligaments; their diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and prevention. Medicine Science & Sports 1976; 8:133–144. ![]()

43. Akeson, WH, Amiel, D, Abel, MF, Effects of immobilization on joints. Clin Orthop 1987; 219:33. ![]()

44. Matthiass, AH, Immobilisation und Druckbelastung in ihrer Wirkung auf die Gelenke. Arch Orthop Unfall-Chir 1966; 60:380. ![]()

45. Cotta, H, Pathophysiologie des Knorpelschadens. Hefte Unfallheikunde 1976; 127:1–22. ![]()

46. Dustmann, HO, Knorpelveränderungen beim Hämarthros unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Ruhigstellung. Arch Orthop Unfall-Chir 1971; 71:148. ![]()

47. Giucciardi, E, Some observations on the effect of blood and fibrinolytic enzyme on articular cartilage in the rabbit. J Bone Joint Surg 1967; 49B:342–350. ![]()

48. Sood, SC, A study on the effects of experimental immobilisation on rabbit articular cartilage. J Anat 1971; 108:497. ![]()

49. Videman, T, Connective tissue and immobilisation: key factors in musculoskeletal degeneration? Clin Orthop Rel Res 1987; 221:26–32. ![]()

50. Ratcliffe, A, Mow, VC. Articular cartilage. In: Comper WD, ed. Extracellular Matrix, vol I, Tissue Function. Amsterdam: Harwood; 1996:234–306.

51. Salter, RB, Simmonds, DF, Malcolm, BW, et al, The biological effect of continuous passive motion on the healing of full-thickness defects in articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg 1980; 62A:1232–1251. ![]()

52. Gerber, CH, Matter, P, Chrisman, OD, Langhans, M, Funktionelle Rehabilitation nach komplexen Knieverletzungen. Wissenschaftliche Grundlagen und Praxis. Schweiz Z Sprtmed 1980; 28:37–56. ![]()

53. Appell, H-J, Muscular atrophy following immobilization. A review. Sports Med. 1990;10(1):42–58. ![]()

54. Maroudas, A, Distribution and diffusion of solutes in articular cartilage. Biophys J 1970; 10:365. ![]()

55. Tittel, K. Zur Anpassungsfähigkeit einiger Gewebe des Haltungs- und Bewegungsapparates an Belastungen unterschiedlicher Intensität und Dauer. Med Sport. 1973; 13:147–156.

56. Robbins, JR, Evanko, SP, Vogel, KG, Mechanical loading and TGF-beta regulate proteoglycan synthesis in tendon. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;342(2):203–211. ![]()

57. Ehricht, HG. Zur Diagnostik und Therapie der veralteten Bandruptur am oberen Sprunggelenk fibular. Med Sport. 1978; 18:274–280.

58. Smillie, IS. Injuries to the Knee Joint, 5th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1978.

59. Cooper, RR, Alterations during immobilization and regeneration of skeletal muscles in cats. J Bone Joint Surg 1972; 54A:919–951. ![]()

60. Järvinen M. Healing of a crush injury in rat striated muscle with special reference to treatment by early mobilization or immobilization. Dissertation Turku, 1976.

61. Vries de, HA, Quantitative EMG investigation of the spasm theory of muscle pain. Am J Phys Med 1966; 45:119–134. ![]()

62. Bobbert, MF, Hollander, AP, Huijing, PA, Factors in delayed onset muscular soreness of man. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1986; 18:75–81. ![]()

63. Stauber, WT, Eccentric action of muscles; physiology, injury and adaption. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 1989; 17:157–185. ![]()

64. van Wingerden, BAM. Ijstherapie in de sport – Indicatie of contraindicatie. Kine 2000, Eur Tijdschr Kinesither. 1993; 1.

65. Travell, J, Ethyl chloride spray for painful muscle spasm. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1952; 32:291–298. ![]()

66. Waylonis, GW, The physiologic effects of ice massage. Arch Phys Med Rehab 1967; 48:37–47. ![]()

67. Obremskey, WT, Seaber, AV, Ribbeck, BM, Garrett, WE, Jr. Biomechanical and histological assessment of a controlled muscle strain injury treated with piroxicam. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1988; 13:338.

68. Clanton, TO, Coupe, KJ, Hamstring strains in athletes: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(4):237–248. ![]()

69. Beaulieu, JE. Developing a stretching program. Physician Sportsmed. 1981; 9:59–65.

70. Stanish, WD, Hubley-Kozey, CL. Separating fact from fiction about a common sports activity: can stretching prevent athletic injuries? J Musculoskeletal Med. 1984; 25–32.

71. Wiktorsson-Moller, M, Oberg, B, Ekstrand, J, Gillquist, J, Effects of warming up, massage, and stretching on range of motion and muscle strength in the lower extremity. Am J Sports Med 1983; 11:249–252. ![]()

72. Garrett, WE, Jr., Muscle strain injuries: clinical and basic aspects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22(4):436–443. ![]()

73. Ryan, JB, Wheeler, JH, Hopkinson, WJ, Arciero, RA, Kolakowski, KR, Quadriceps contusions. West Point update. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):299–304. ![]()

74. Beiner, JM, Jokl, P, Cholewicki, J, Panjabi, MM, The effect of anabolic steroids and corticosteroids on healing of muscle contusion injury. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(1):2–9. ![]()

75. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol 1. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

76. Penniello, MJ, Chapon, F, Olivier, D, et al, Myositis ossificans progressiva. Arch Pediatr. 1995;2(1):34–38. ![]()

77. Traore, O, Yiboudo, J, Cisse, R, et al, Non-traumatic circumscribed myositis ossificans. Apropos of a bilateral localization. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1998;84(1):79–83. ![]()

78. Howard, CB, Porat, S, Bar-On, E, Nyska, M, Segal, D, Traumatic myositis ossificans of the quadriceps in infants. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;7(1):80–82. ![]()

79. Weinstein, L, Fraerman, S, Difficulties in early diagnosis of myositis ossificans. JAMA 1954; 154:994. ![]()

80. Gilmer, W, Anderson, L. Reactions of the somatic tissue which progress to bone formation. South Med J. 1959; 52:1432.

81. Huss, CD, Puhl, JJ, Myosititis ossificans of the upper arm. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8(6):419. ![]()

82. Puddu, G, Ippolito, E, Postacchini, F, A classification of Achilles tendon disease. Am J Sports Med 1976; 4:145–150. ![]()

83. Khan, KM, Cook, JL, Kannus, P, et al, Time to abandon the ‘tendinitis’ myth. Br Med J 2002; 324:626–667. ![]()

84. Maffulli, N, Khan, KM, Puddu, G, Overuse tendon conditions: time to change a confusing terminology. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(8):840–843. ![]()

85. Carr, AJ, Norris, SH, The blood supply of the calcanean tendon. J Bone Joint Surg 1989; 71B:100–101. ![]()

86. Ahmed, IM, Lagopoulos, M, McConnell, P, Soames, RW, Sefton, GK, The blood supply of the Achilles tendon. J Orthop Res. 1998;16(5):591–596. ![]()

87. Katzer, A, Wening, JV, Becker-Manich, HU, Lorke, DE, Jungbluth, KH, Rotator cuff rupture. Vascular supply and collagen fiber processes as pathogenetic factors. Unfallchirurgie. 1997;23(2):52–59. ![]()

88. Kannus, P, Józsa, L, Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(10):1507–1525. ![]()

89. Tallon, C, Maffulli, N, Ewen, SW, Ruptured Achilles tendons are significantly more degenerated than tendinopathic tendons. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(12):1983–1990. ![]()

90. Kummer, FJ, Zuckerman, JD, The incidence of full thickness rotator cuff tears in a large cadaveric population. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1995;54(1):30–31. ![]()

91. Milgrom, C, Schaffler, M, Gilbert, S, van Holsbeeck, M, Rotator cuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand dominance and gender. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;77B(2):296–298. ![]()

92. Gelberman, RH, Vande Berg, JS, Lundborg, GN, Akeson, WH, Flexor tendon healing and restoration of the gliding surfaces. J Bone Joint Surg 1983; 65A:70–80. ![]()

93. Takai, S, Woo, SL, Horibe, S, Tung, DK, Gelberman, RH, The effects of frequency and duration of controlled passive mobilization on tendon healing. J Orthop Res. 1991;9(5):705–713. ![]()

94. Stenho-Bittel, L, Reddy, GK, Gum, S, Enwemeka, CS, Biochemistry and biomechanics of healing tendon. Part I. Effects of rigid plaster casts and functional casts. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30(6):788–793. ![]()

95. Buckwalter, JA, Effects of early motion on healing of musculoskeletal tissues. Hand Clin. 1996;12(1):113–124. ![]()

96. Peterson, L, Althoff, B, Renström, P, Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle joint, 1979.

97. Cass, JR, Ankle instability: comparison of primary repair and delayed reconstruction after long-term follow-up study. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1985; 198:110–117. ![]()

98. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol II, 11th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1984.

99. Larsen, E, Taping the ankle for chronic instability. Acta Orthop Scand 1984; 55:551–553. ![]()

100. Freeman, MAR, The etiology and prevention of functional instability of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg 1965; 47B:678–685. ![]()

101. De Carlo, MS, Talbot, RW, Evaluation of ankle joint proprioception following injection of the anterior talofibular ligament. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1986; 8:70–76. ![]()

102. Oostendorp, RAB. Functionele instabiliteit na het inversie-trauma van enkel en voet: een effectonderzoek pleisterbandage versus pleisterbandage gecombineerd met fysiotherapie. Geneeskd Sport. 1987; 20(2):323–329.

103. Lynch, SA, Renstrom, PA, Treatment of acute lateral ankle ligament rupture in the athlete. Conservative versus surgical treatment. Sports Med. 1999;27(1):61–71. ![]()

104. Fetto, JF, Marshall, JL, Medial collateral ligament injuries to the knee: a rationale for treatment. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1978; 132:206. ![]()

105. Hastings, DE, The non-operative management of collateral ligament injuries of the knee joint. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1980; 147:22. ![]()

106. Indelicato, PA, Non-operative treatment of complete tears of the medial collateral ligament of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg 1983; 65A:323. ![]()

107. Jones, RE, Henley, B, Francis, P, Non-operative management of isolated grade III collateral ligament injury in high school football players. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1986; 213:137–140. ![]()

108. Indelicato, PA, Hermansdorfer, J, Huegel, M, Non-operative management of complete tears of the medial collateral ligament of the knee in intercollegiate football players. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1990; 256:174–177. ![]()

109. Kannus, P, Järvinen, M, Non-operative treatment of acute knee ligament injuries. Sport Med. 1990;9(4):244–260. ![]()

110. Crowninshield, RD, Pope, MH, Strength and failure characteristics of rat medial collateral ligaments. J Trauma 1969; 16:99. ![]()

111. Wiggins, ME, Fadale, PD, Ehrlich, MG, Walsh, WR, Effects of local injection of corticosteroids on the healing of ligaments. A follow-up report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77A(11):1682–1691. ![]()

112. Campbell, RB, Wiggins, ME, Canistra, LM, Fadale, PD, Akelman, E, Influence of steroid injection on ligament healing in the rat. Clin Orthop 1996; 332:242–253. ![]()

113. Hughston, JC, Eilers, AF, The role of the posterior oblique ligament in repairs of acute medial collateral ligament tears of the knee. J Joint Bone Surg 1973; 55A:923–940. ![]()