Chapter 29 Congenital Anomalies of Vena Caval Connection

Anomalous vena caval connections comprise a wide range of malformations that vary from minor to major and that occur in isolation or with coexisting congenital heart disease. Persistent left superior vena cava occurs in 0.3% of the general population and in 4.3% of congenital heart disease.1 A left-sided inferior vena cava occurs in 0.2% to 0.5% of the general population.1 This chapter focuses on isolated anomalous vena caval connections in situs solitus hearts (Table 29-1). Anomalies of vena caval connection with cardiac malpositions or with atrial isomerism are dealt with in Chapter 3.

Table 29-1 Congenital Anomalies of Vena Caval Connection

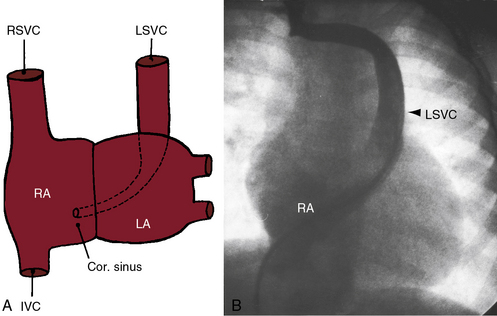

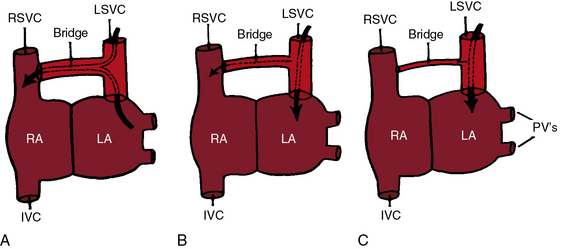

In early embryonic development, the common cardinal veins are bilaterally symmetric and are potentially responsible for bilateral superior vena cavae.2 The left common cardinal vein initially drains into the left portion of the sinus venosus, which becomes the coronary sinus.2 Failure of obliteration of the left common cardinal vein results in persistent connection of a left superior vena cava to the coronary sinus (Figure 29-1),2 a relatively common anomaly estimated at 0.3% to 0.5% of the general population and 1.5% to 10% of patients with congenital heart disease.3 An isolated left superior vena cava in itself produces no physiologic derangements when it drains harmlessly into the right atrium via the coronary sinus (see Figure 29-1). However, the coronary sinus dilates sometimes appreciably,4 especially if there is atresia of its right atrial orifice5 or absence of the right superior vena vava.6,7 When the right superior cava is absent, the sinus node pacemaker is absent because the pacemaker is normally located at the junction of the right superior vena cava and the morphologic right atrium.8–11 A persistent left superior vena cava is a significant anomaly when it connects to the left atrium (Figures 29-2 and 29-3).12–14 The coronary sinus is usually absent15 with partial or complete unroofing of its anterosuperior wall. Unroofing results in a connection between the left atrium and the right atrium—a coronary sinus type of atrial septal defect (see Chapter 15).16 A right-to-left shunt coexists through the left superior vena caval to left atrial connection.14,17 An absent coronary sinus with bilateral superior vena cavae (right superior cava connected to the right atrium, left superior cava connected to the left atrium) is thought to represent a developmental complex.18 If the right superior vena cava is absent or atretic (see Figure 29-3), the innominate vein crosses the midline and terminates in the left superior vena cava.19 The left atrium occasionally receives the azygos vein, the hepatic vein, or the coronary sinus,14 variations that are not considered in this chapter.

Direct connections between vena cavae and left atrium are uncommon.7,20,21 Rarely, a right superior vena cava connects to the left atrium.22–24 Still more rarely, a right superior vena cava connects to the left atrium, and a left superior vena cava connects to the right atrium.25 Connection of a right superior vena cava to the left atrium must be distinguished from drainage of a right superior vena cava into both atria caused by a contiguous superior vena caval sinus venosus atrial septal defect (see Chapter 15).20 When a right superior vena cava is congenitally absent (see Figure 29-3), brachiocephalic veins join a left superior vena cava that connects to the coronary sinus.6,26

Bilateral superior vena cavae3 are illustrated in Figure 29-2. The innominate bridge that connects the two superior cavae may be widely patent, narrow, or atretic (see Figure 29-2), and the size of the left superior vena cava ranges from large to rudimentary.3 Bilateral superior vena cavae with atrial isomerism are dealt with in Chapter 3.

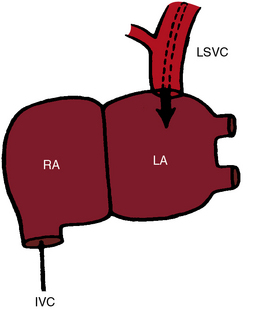

Anomalous connection of the inferior vena cava to the left atrium consists of a morphogenetic spectrum represented by combinations of persistence of the valve of the right sinus venosus, fusion of the valve with the septum secundum, and incomplete development of the atrial septum.27 The inferior vena cava penetrates the diaphragm at its expected site. An enlarged azygos vein may arise from the anomalous inferior cava and convey inferior caval blood into the right atrium (Figure 29-4).21,28,29 An isolated left-sided abdominal inferior vena cava usually crosses to the right after receiving the renal veins, then penetrates the diaphragm and enters the right atrium at the normal site. A distinction must be made between connection of the inferior vena cava to the left atrium and anomalous inferior vena caval drainage into the left atrium from persistence of a large Eustachian valve (right valve of the sinus venosus) that directs flow toward a patent foramen ovale or across an ostium secundum atrial septal defect (see Chapter 15).27

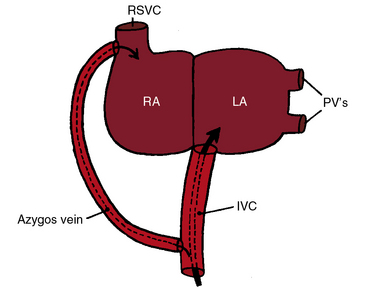

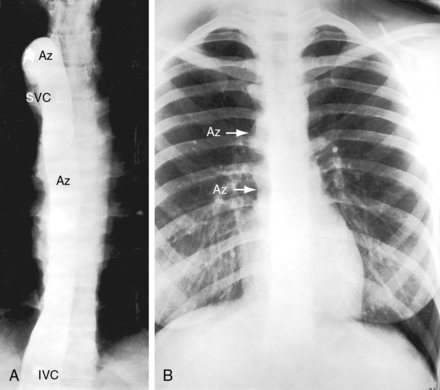

Inferior vena caval interruption with azygous continuation is rare as an isolated malformation and is of no physiologic significance but can be mistaken for the descending thoracic aorta (Figure 29-5).30 Interruption is immediately proximal to the renal veins and continues into a dilated azygos vein that enters the thorax to the right of the aorta, runs in the posterior mediastinum, and connects to a right superior vena cava (see Figure 29-5). There is an association with congenital absence of the portal vein.31 Inferior vena caval interruption with azygos continuation and left isomerism are dealt with in Chapter 3.

Anomalous connection of either vena cava to the left atrium is rare enough, but connection of the right superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava to the left atrium—total anomalous systemic venous connection—is even rarer (Figures 29-6 and 29-7). 7,20,32 Survival depends on adequate mixing through an interatrial communication.

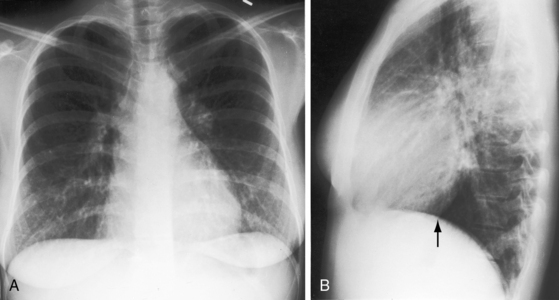

Figure 29-7 X-rays from the 28-year-old woman with total anomalous systemic venous connection whose electrocardiogram is shown in Figure 29-6. A, The size and configuration of the heart are normal. Pulmonary vascularity is not reduced. Increased markings in the left lower lung fields are superimposed breast tissue. B, In the lateral projection, the inferior vena caval shadow is absent (arrow).

The physiologic consequences of anomalous vena caval connections to the left atrium take into account two variables: (1), the direction and volume of blood flow through the connection; and (2), the effect of the connection on the amount of blood flow entering the right and left sides of the heart. Flow patterns are complex when a persistent left superior vena cava communicates with the left atrium (see Figure 29-2).14,17 The left superior vena cava may be the only superior cava (see Figure 29-3), or bilateral superior cavae may fail to communicate with each other because of stenosis or atresia of the innominate bridge (see Figures 29-2B and C). All or nearly all of left superior vena caval blood is then channeled into the left atrium (Figure 29-2B and C), so cyanosis is obligatory. Alternatively, when bilateral superior vena cavae communicate freely through a nonrestrictive innominate bridge, the direction of blood flow is from the left atrium into the anomalous left superior vena cava, across the innominate bridge and into the right superior vena cava (Figure 29-2A).17,33 The pathway constitutes a left-to-right shunt, so cyanosis is absent.14 With this exception, communications between vena cavae and left atrium result in right-to-left shunts and in a decrease in systemic arterial oxygen saturation. When a right superior vena cava connects to the left atrium, caval blood flow is into the left atrium, so cyanosis is inevitable. When the inferior vena cava connects to the left atrium, unoxygenated blood is directed into the left atrium despite a large azygos vein, so cyanosis is obligatory (see Figure 29-4).

Now consider the relative volume of blood flowing through the two sides of the heart in the presence of vena caval–to–left atrial connections. Normally, the entire systemic venous return from the superior and inferior vena cavae enters the right side of the heart, and the entire pulmonary venous return from the pulmonary veins enters the left side of the heart. If one vena cava connects to the left atrium, the right side of the heart is effectively bypassed, so right ventricular output and pulmonary blood flow fall reciprocally.34 Left ventricular output theoretically remains unchanged because the increment in anomalous caval flow into the left atrium is matched by the reciprocal decrement in pulmonary venous flow. Accordingly, as systemic venous return to the left atrium increases, pulmonary venous return to the left atrium decreases by the same amount, so total blood flow to the left side of the heart remains unchanged. In the absence of compensatory mechanisms, anomalous caval connections to the left atrium should be associated with reduced pulmonary flow and normal systemic flow,34 patterns that should pertain irrespective of whether the superior or inferior vena cava connects anomalously. Do these circulatory patterns really exist? Clinical and experimental observations indicate that right atrial and right ventricular pressures are normal or low34 and pulmonary blood flow is usually,34 but not always, reduced. Necropsy descriptions of a small right atrium and a small right ventricle are relevant.35 However, left ventricular output tends to be moderately increased.34 The mechanisms responsible for these deviations from theoretical blood flow patterns are not known.

When the superior vena cava and inferior vena cava both connect to the left atrium (total anomalous systemic venous connection), flow patterns are modified by obligatory mixing at atrial level. The left atrium receives blood from both cavae and from the pulmonary veins. Part of this mixture reaches the left ventricle directly across the mitral valve, and the remainder enters the right side of the heart across an atrial septal defect. Pulmonary blood flow is not increased even in the presence of a nonrestrictive atrial septal defect and normal pulmonary vascular resistance (see Figure 29-7).

History

Isolated anomalous vena caval connection to the left atrium has an equal gender distribution. Cyanosis dates from birth or infancy20,27 unless bilateral superior cavae are connected by a nonrestrictive innominate bridge (see Figure 29-2A). Despite conspicuous cyanosis, there is a paucity of symptoms.21,27 the syndrome of cyanosis and clubbing with normal heart. Adult survival is expected, with longevities recorded in the sixth, seventh, and eighth decades.12,20 Effort intolerance, dyspnea, and light-headedness develop late if at all and are generally mild.20,21 One man tolerated training in the armed forces.27 Brain abscess and paradoxical embolus have been reported.20,23

The cause of death is usually unrelated to the isolated congenital anomalies of vena caval connection. However, unexplained sudden death has been reported with isolated left superior vena caval connection to the coronary sinus, especially if the right superior vena cava is absent.9

Physical appearance

Cyanosis and clubbing are the only abnormalities of physical appearance.20 Cyanosis increases with effort because caval venous return increases. Cyanosis is greater when the inferior vena cava connects to the left atrium because approximately twice as much blood is delivered to the heart via the inferior vena cava (see previous).34,36 A large azygos venous system allows substantial inferior vena caval flow into the right atrium and proportionately less flow into the left atrium (see Figure 29-4), so cyanosis is relatively mild.21 A superior vena cava that connects to the left atrium (see Figure 29-3) is accompanied by conspicuous cyanosis. When a nonrestrictive innominate bridge joins bilateral superior vena cavae, cyanosis is absent because the direction of flow is from the left atrium into the anomalous left superior vena cava (see Figure 29-2A).17

Arterial pulse and jugular venous pulse

The arterial pulse is normal because left ventricular stroke volume increases little if at all.

Precordial movement and palpation

The left ventricular impulse is normal or only moderately increased, which reflects the normal or only moderate increase in systemic output. A right ventricular impulse is absent. These physical signs indicate that cyanosis is occurring with a dominant left ventricle, an important observation in the clinical recognition of cyanotic congenital heart disease (see Box 1-1).

Auscultation

Left ventricular stroke volume is seldom sufficient to generate a flow murmur into the aorta.20,21 The second heart sound is single because decreased right ventricular stroke volume and decreased pulmonary capacitance result in early pulmonary valve closure and synchrony or near synchrony of the two components.20 The intensity of the pulmonary component is normal or reduced because pulmonary arterial pressure is normal or low.34

Electrocardiogram

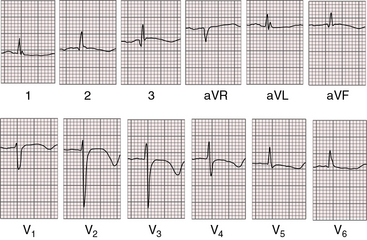

When a left superior vena cava connects to the coronary sinus (see Figure 29-1), the atrial rhythm may be ectopic and abnormalities of atrioventricular conduction may coexist.2,8,9 When a right superior vena cava is absent or connects to the left atrium, the sinus node is absent, so the atrial focus is ectopic and the P wave axis is abnormal (see Figure 29-6).11 Atresia or absence of the segment of superior vena cava adjacent to the right atrium is accompanied by developmental abnormalities of the sinus node and an ectopic atrial focus.9

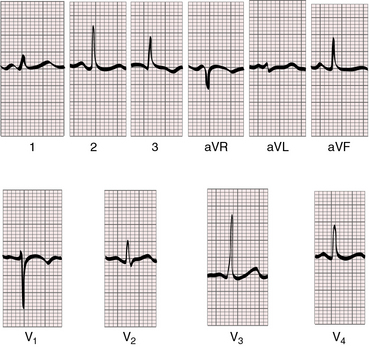

The QRS pattern is normal with vena caval–to–left atrial connections (Figure 29-8). Adult survival anticipates age-related electrocardiographic abnormalities.12,20,21 Right ventricular hypertrophy is absent because flow into the right side of the heart is normal or reduced. Left ventricular electrical forces retain their normal adult dominance (Figures 29-6 and 29-9), but the modest increment in left ventricular volume is seldom sufficient to cause hypertrophy.

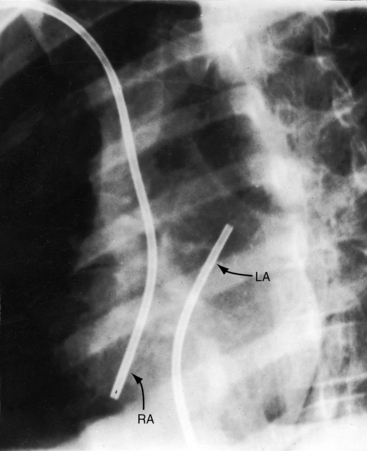

Figure 29-8 Left anterior oblique projection from a 9-year-old girl with isolated inferior vena caval connection to the left atrium. One catheter entered the right atrium (RA) from the superior vena cava, and a second catheter entered the left atrium (LA) from the inferior vena cava (see Figure 29-6 for electrocardiogram).

(With permission, from Venables AW. Isolated drainage of the inferior vena cava to the left atrium. British Heart Journal 1963;25:545.)

X-Ray

The size and configuration of the heart are normal (see Figure 29-8),20,21,35 even when both superior and inferior vena cavae connect to the left atrium (see Figure 29-7). A left superior vena cava may form a concave or crescentic shadow as it emerges from beneath the middle third of the left clavicle.14,17,37 When the inferior vena cava communicates with the left atrium, the inferior vena caval shadow is absent from its expected location at the angle formed by the posterior cardiac silhouette and the diaphragm (see Figure 29-7B). An inferior vena caval shadow is also absent when there is inferior caval interruption with azygos continuation (see Figure 29-5). The azygos vein ascends along the right edge of the vertebral column, forming a knuckle as it courses anteriorly to join the right superior vena cava (see Figure 29-5).

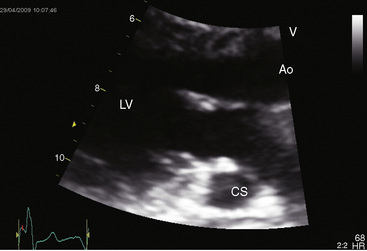

Echocardiogram

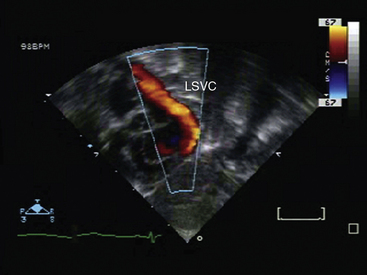

Echocardiography with color flow and contrast imaging establishes the diagnoses of most if not all anomalies of vena caval connection described in this chapter,1,16,38–43 including intrauterine.44 A dilated coronary sinus in the parasternal long-axis view arouses suspicion of a hitherto unsuspected connection of a left superior vena cava to the coronary sinus (Figure 29-10 and Video 29-1).45 The coronary sinus is absent when a left superior vena cava connects directly to the left atrium (see Figure 29-2). Color flow imaging confirms the course of a persistent left superior vena cava (Figure 29-11 and Video 29-2), which can sometimes be visualized together with the innominate bridge associated with bilateral cavae (see Figure 29-2). When the right superior vena cava is absent, a persistent left superior vena cava is imaged along the left side of the aorta.46,47

Contrast echocardiography identifies specific vena caval to left atrial connections.38,40,48 When a left superior vena cava connects directly to the left atrium, injection of echo contrast into the left antecubital vein is followed by immediate opacification of the left atrium.38 Conversely, when a right superior vena cava connects directly to the left atrium, injection of contrast into the right antecubital vein promptly opacifies the left atrium.38 Contrast echocardiography is more complex when the inferior vena caval connects to the left atrium49 because contrast material injected into the femoral vein may appear in the right as well as the left atrium depending on the size of the azygos vein that leaves the inferior vena cava and joins the right atrium via a right superior vena cava (see Figure 29-4). When a right superior vena cava and an inferior connect both connect to the left atrium (see Figure 29-7), injection of contrast into the right antecubital vein and into the femoral vein result in a combination of the patterns just described.

1 Guray Y., Yelgec N.S., Guray U., et al. Left-sided or transposed inferior vena cava ascending as hemiazygos vein and draining into the coronary sinus via persistent left superior vena cava: case report. Int J Cardiol. 2004;93:293-295.

2 Nsah E.N., Moore G.W., Hutchins G.M. Pathogenesis of persistent left superior vena cava with a coronary sinus connection. Pediatric Pathol. 1991;11:261-269.

3 Buirski G., Jordan S.C., Joffe H.S., Wilde P. Superior vena caval abnormalities: their occurrence rate, associated cardiac abnormalities and angiographic classification in a paediatric population with congenital heart disease. Clin Radiol. 1986;37:131-138.

4 Ascuitto R.J., Ross-Ascuitto N.T., Kopf G.S., et al. Persistent left superior vena cava causing subdivided left atrium: diagnosis, embryological implications, and surgical management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987;44:546-549.

5 Imai S., Matsubara T., Yamazoe M., et al. Atresia of the right atrial orifice of the coronary sinus with persistent left superior vena cava: a case report. J Cardiol. 1999;34:341-344.

6 Chan K.L., Abdulla A. Images in cardiology. Giant coronary sinus and absent right superior vena cava. Heart. 2000;83:704.

7 Winter S. Persistent left superior vena cava. Survey of world literature and report of 30 additional cases. Angiology. 1954;5:90.

8 James T.N., Marshall T.K., Edwards J.E. De subitaneis mortibus. XX. Cardiac electrical instability in the presence of a left superior vena cava. Circulation. 1976;54:689-697.

9 Lenox C.C., Hashida Y., Anderson R.H., Hubbard J.D. Conduction tissue anomalies in absence of the right superior caval vein. Int J Cardiol. 1985;8:251-260.

10 Momma K., Linde L.M. Abnormal rhythms associated with persistent left superior vena cava. Pediatr Res. 1969;3:210-216.

11 Langford E.J., Sulke A.N., Curry P.V. Atrial permanent pacing for sinus node dysfunction with absent right superior vena cava. Int J Cardiol. 1993;40:177-178.

12 Arsenian M.A., Anderson R.A. Anomalous venous connection of the superior vena cava to the left atrium. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:989-990.

13 Kabbani S.S., Feldman M., Angelini P., Leachman R.D., Cooley D.A. Single (left) superior vena cava draining into the left atrium. Surgical repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 1973;16:518-525.

14 Taybi H., Kurlander G.J., Lurie P.R., Campbell J.A. Anomalous ssystemic venous connection to the left atrium or to a pulmonary vein. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1965;94:62-77.

15 Wiles H.B. Two cases of left superior vena cava draining directly to a left atrium with a normal coronary sinus. Br Heart J. 1991;65:158-160.

16 Chen M.C., Hung J.S., Chang K.C., et al. Partially unroofed coronary sinus and persistent left superior vena cava: intracardiac echocardiographic observation. J Ultrasound Med. 1996;15:875-879.

17 Odman P. A persistent left superior vena cava communicating with the left atrium and pulmonary vein. Acta Radiologica. 1953;40:554-560.

18 Foster E.D., Baeza O.R., Farina M.F., Shaher R.M. Atrial septal defect associated with drainage of left superior vena cava to left atrium and absence of the coronary sinus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1978;76:718-720.

19 De Leval M.R., Ritter D.G., Mcgoon D.C., Danielson G.K. Anomalous systemic venous connection. Surgical considerations. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975;50:599-610.

20 Shapiro E.P., Al-Sadir J., Campbell N.P., et al. Drainage of right superior vena cava into both atria. Review of the literature and description of a case presenting with polycythemia and paradoxical embolization. Circulation. 1981;63:712-717.

21 Venables A.W. Isolated drainage of the inferior vena cava to the left atrium. Br Heart J. 1963;25:545-548.

22 Bharati S., Lev M. Direct entry of the right superior vena cava into the left atrium with aneurysmal dilatation and stenosis at its entry into the right atrium with stenosis of the pulmonary veins: a rare case. Pediatr Cardiol. 1984;5:123-126.

23 King R.E., Plotnick G.D. Isolated right superior vena cava into the left atrium detected by contrast echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1991;122:583-586.

24 Tandon R. Anomalous drainage of right superior vena cava into the left atrium. Indian Heart J. 1999;51:345.

25 Leys D., Manouvrier J., Dupard T., et al. Right superior vena cava draining into the left atrium with left superior vena cava draining into the right atrium. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:855.

26 Bartram U., Van Praagh S., Levine J.C., et al. Absent right superior vena cava in visceroatrial situs solitus. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:175-183.

27 Meyers D.G., Latson L.A., Mcmanus B.M., Fleming W.H. Anomalous drainage of the inferior vena cava into a left atrial connection: a case report involving a 41-year-old man. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1989;16:239-244.

28 Cabrera A., Arriola J., Llorente A. Anomalous connection of inferior vena cava to the left atrium. Int J Cardiol. 1994;46:79-81.

29 Genoni M., Jenni R., Vogt P.R., Germann R., Turina M.I. Drainage of the inferior vena cava to the left atrium. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:543-545.

30 Blanchard D.G., Sobel J.L., Hope J., et al. Infrahepatic interruption of the inferior vena cava with azygos continuation: a potential mimicker of aortic pathology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1998;11:1078-1083.

31 Le Borgne J., Paineau J., Hamy A., et al. Interruption of the inferior vena cava with azygos termination associated with congenital absence of portal vein. Surg Radiol Anat. 2000;22:197-202.

32 Pugliese P., Murzi B., Redaelli S., Eufrate S. Total anomalous systemic venous drainage into the left atrium. Report of a case of successful surgical correction. G Ital Cardiol. 1983;13:62-67.

33 Lam W., Danoviz J., Witham D., Wyndham C., Rosen K.M. Left-to-right shunt via left superior vena cava communication with left atrium. Chest. 1981;79:700-702.

34 Hultgren H.N., Gerbode F. A physiological study of experimental left atrium inferior vena caval anastomoses. Am J Physiol. 1954;177:164-169.

35 Vaquez-Perez J., Frontera-Izquierdo P. Anomalous drainage of the right superior vena cava into the left atrium as an isolated anomaly. Rare case report. Am Heart J. 1979;97:89-91.

36 Levy S.E., Blalock A. Fractionation of the output of the heart and of the oxygen consumption of normal unanesthetized dogs. Am J Physiol. 1937;118:368.

37 Gensini G.G., Caldini P., Casaccio F., Blount S.G.Jr. Persistent left superior vena cava. Am J Cardiol. 1959;4:677-685.

38 Foale R., Bourdillon P.D., Somerville J., Rickards A. Anomalous systemic venous return: recognition by two-dimensional echocardiography. Eur Heart J. 1983;4:186-195.

39 Hibi N., Fukui Y., Nishimura K., et al. Cross-sectional echocardiographic study on persistent left superior vena cava. Am Heart J. 1980;100:69-76.

40 Pan C., Chen C., Wang S., Al E. Echocardiographic evidence for drainage of a persistent left supeior vena cava into the left atium. J Cardiovasc Ultrasonog. 1984;3:329.

41 Chin A.J. Subcostal two-dimensional echocardiographic identification of right superior vena cava connecting to left atrium. Am Heart J. 1994;127:939-941.

42 Kogon B.E., Fyfe D., Butler H., Kanter K.R. Anomalous drainage of the inferior vena cava into the left atrium. Pediatr Cardiol. 2006;27:183-185.

43 Miraldi F., Carbone I., Ascarelli A., Barretta A., D’Angeli I. Double superior vena cava: right connected to left atrium and left to coronary sinus. Int J Cardiol. 2009;131:e78-e80.

44 Galindo A., Gutierrez-Larraya F., Escribano D., Arbues J., Velasco J.M. Clinical significance of persistent left superior vena cava diagnosed in fetal life. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:152-161.

45 Gonzalez-Juanatey C., Testa A., Vidan J., et al. Persistent left superior vena cava draining into the coronary sinus: report of 10 cases and literature review. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27:515-518.

46 Srivastava V., Mishra P., Kumar S., et al. Persistent left SVC with absent right SVC: a rare anomaly. J Card Surg. 2007;22:535-536.

47 Waikar H.D., Lahie Y.K.M., De Zoysa L., Chand P., Kamalanesan R.P.P. Systemic venous anomalies: absent right superior vena cava with persistent left superior vena cava. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18:332-335.

48 Gorenflo M., Sebening C., Ulmer H.E. Anomalous connection of the right superior caval vein to the morphologically left atrium. Cardiol Young. 2006;16:184-186.

49 Burri H., Vuille C., Sierra J., et al. Drainage of the inferior vena cava to the left atrium. Echocardiography. 2003;20:185-189.