Congenital and Neonatal Conditions

Normal Adrenal

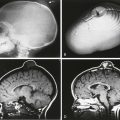

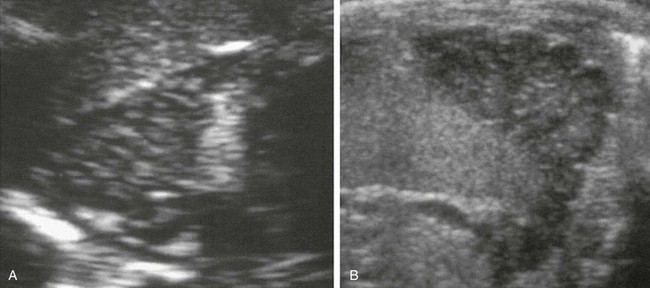

At birth, the adrenal glands are relatively large because of the presence of the fetal adrenal cortex, which accounts for about 80% of the gland.1 Because of this, both adrenals are easily visualized by using ultrasonography in the neonate (Fig. 122-1).

Figure 122-1 A longitudinal sonogram of a normal adrenal (arrows) in a 1-day-old newborn.

The central hyperechoic stripe represents the central veins, connective tissue, medullary tissue, and congested sinusoids of the inner part of the fetal cortex. The surrounding hypoechoic zone represents the less congested outer part of the fetal cortex and the thin peripheral definitive cortex. The surface of the gland is smooth.

On ultrasonography, the normal adrenal gland has a central hyperechoic stripe surrounded by a hypoechoic rim. The hypoechoic rim represents the fetal and the peripheral definitive cortex (see Fig. 122-1). The central hyperechoic stripe includes the medulla, the central veins of the adrenal, connective tissue, and probably also part of the fetal cortex.2 The surface of the adrenals is smooth or only slightly undulating (see Fig. 122-1). The easiest and most useful measurement of the adrenal is the limb width, which should normally be less than 4 mm.3

Abnormalities of Shape and Size

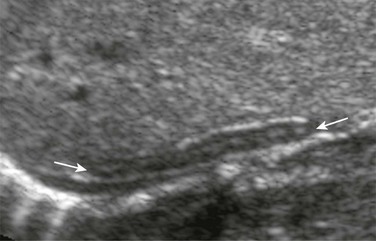

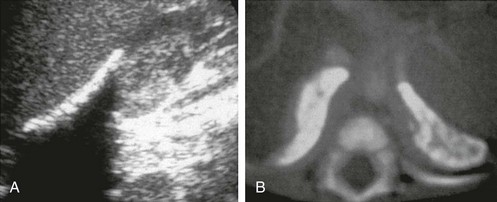

Overview and Imaging: A straight or discoid shape of the adrenal gland is seen on ultrasonography in association with certain congenital anomalies of the ipsilateral kidney, in which the kidney either is absent from its normal position in the renal fossa or is extremely small as a result of antenatal damage and dysplasia.4 The adrenal gland otherwise develops normally but assumes a flattened, discoid shape (Fig. 122-2). On ultrasonography, the adrenal retains its normal pattern of echogenicity. Straight adrenals are longer than otherwise normal glands, and they tend to be slightly thicker.

Figure 122-2 A longitudinal sonogram of the right adrenal gland shows a straight adrenal (arrows) in a patient with right renal agenesis.

The adrenal gland is straight and lacks the angulation and shapes illustrated in Figure 122-1. The central hyperechoic stripe, surrounding hypoechoic zone, and smooth surface are preserved.

Horseshoe Adrenal

Overview and Imaging: Horseshoe adrenal is a rare congenital anomaly, in which the right and left adrenal glands are fused. It is often associated with other anomalies of the kidneys and the central nervous system, asplenia with visceral heterotaxy, and other anomalies.5

A horseshoe adrenal appears on ultrasonography as a band of normal adrenal tissue crossing the midline in the upper abdomen above the kidneys (e-Fig. 122-3). The adrenal maintains normal echogenicity. The isthmus of the horseshoe adrenal usually passes behind the aorta, but in asplenia, it usually passes in front of the aorta.5

e-Figure 122-3 A transverse sonogram of the upper abdomen shows a horseshoe adrenal (arrows) in a patient with visceral heterotaxy (asplenia).

The adrenals are fused across the midline, giving a horseshoe shape. The central echogenic stripe and surrounding hypoechoic zone and smooth surface are maintained. The gland lies anterior to the aorta, which is to the right of the midline, and behind the inferior vena cava, which is to the left. (Courtesy Dr. Ulrich Willi, Kinderspital, Zürich, Switzerland.)

Adrenal Congestion

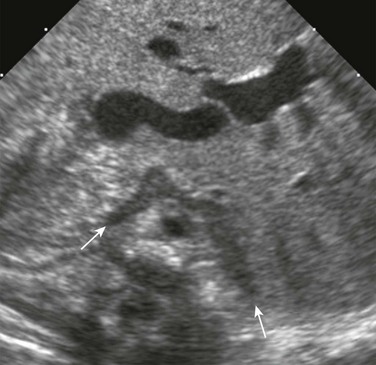

Overview and Imaging: Adrenal congestion may occur in perinatal asphyxia or stress, but the mechanism for this is not clearly understood. On ultrasonography, the glands appear markedly enlarged but maintain their general overall shape and smooth surface (Fig. 122-4). This usually occurs bilaterally but may be seen unilaterally or focally within one gland.2 Loss of the normal central echogenic stripe occurs, and the fetal cortex may become a broad band of slightly increased echogenicity. A very thin peripheral anechoic rim that represents the definitive cortex may be present. Follow-up ultrasonography may show development of focal hypoechoic areas that represent focal hemorrhages or infarction.2 The changes may be reversible and the sonographic pattern may return to that of normal adrenal glands in patients who survive.

Figure 122-4 Adrenal congestion in an 8-day-old full-term boy who developed necrotizing enterocolitis, cardiovascular collapse, and multiorgan failure.

Longitudinal (A) and transverse (B) sonograms reveal marked enlargement of the left adrenal, which, although has retained its normal shape and smooth surface, shows loss of the normal central echogenic stripe. The gland has a more homogeneous low-level echogenicity, and in parts, a peripheral anechoic thin rim is seen. A postmortem histologic examination revealed congestion of the fetal cortex. The peripheral thin rim represents the peripheral definitive cortex.

Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Overview: Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) refers to a group of autosomal recessive disorders, in which an enzymatic defect occurs in the pathway for cortisol biosynthesis in the adrenal cortex. The most common defect is a deficiency of the enzyme 21-hydroxylase, which affects females much more commonly than males.3 This leads to ambiguous sexual development in newborn girls or salt-losing crisis in newborns of either sex.

The diagnosis of CAH is confirmed by the presence of elevated serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP). In addition, in female neonates with genital ambiguity, normal internal genitalia are seen on pelvic ultrasonography, and a normal (46, XX) karyotype. The 17-OHP level is diagnostic only when measured after the third day of life because a relatively high level is present in the immediate neonatal period in a normal newborn. Furthermore, 17-OHP assays may not be easily available. These delays, although relatively short, may contribute to the diagnostic dilemma and heighten parental anxiety. Therefore, ultrasonography in the immediate neonatal period may play a role as some specific signs of CAH are seen on ultrasonography.3

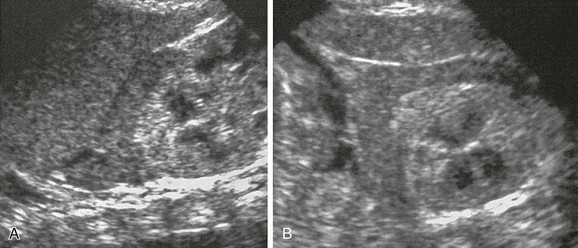

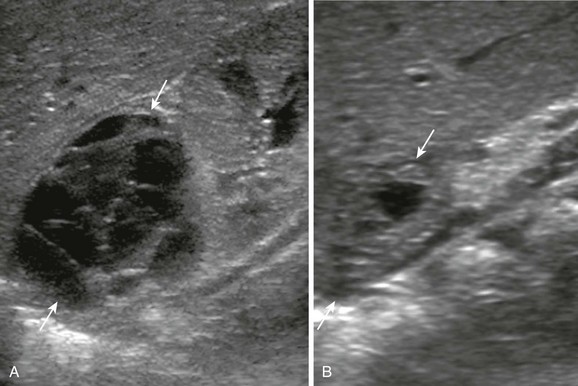

Imaging: Ultrasonography has shown to have a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 100% for the diagnosis of CAH with the use of the composite sonographic signs of adrenal gland size (limb width >4 mm), surface characteristics (cerebriform or crenated appearance), and internal echo pattern (diffusely stippled pattern of echogenicity or less commonly diffuse thickened band of echogenicity) (Fig. 122-5) to make the diagnosis.3 The presence of two or more of the three signs is diagnostic of CAH. These changes may also be present focally within the glands or may be markedly asymmetric between both adrenals.3 Rarely, the adrenals may appear normal, emphasizing the fact that the absence of the signs does not exclude the diagnosis of CAH.

Figure 122-5 Congenital adrenal hyperplasia in a 26-day-old boy.

Longitudinal (A) and transverse (B) sonograms of the left adrenal show marked enlargement of the gland, with a limb width greater than 4 mm in thickness. A clearly lobulated surface to the adrenal is seen better on transverse scan. The central echogenic stripe has been replaced by diffuse stippled echogenicity.

Wolman Disease

Overview: Wolman disease is a rare disorder of lipid metabolism (familial xanthomatosis). This inherited deficiency of lysosomal acid lipase leads to an accumulation of cholesterol esters and triglycerides in many organs, particularly the adrenals.6 The disorder manifests in the early weeks of life, and hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, vomiting, steatorrhea, abdominal distention, and growth failure may exist. The disease is rapidly progressive, and death occurs within the first year.

Imaging: A marked enlargement of both adrenals, which retain their overall shape, is seen on imaging. This is associated with marked, diffuse, punctate calcification (e-Fig. 122-6).6 This can be recognized on plain radiographs of the abdomen and cross-sectional imaging. On ultrasonography, the calcification in Wolman disease appears as dense punctate or granular calcification with marked posterior acoustic shadowing, the latter seldom seen with adrenal hemorrhage. On CT, the large size of both glands and the diffuse pattern of calcification differentiate this condition from resolving adrenal hemorrhage, in which the glands are smaller with more globular calcification.

e-Figure 122-6 Wolman disease.

Marked calcification and enlargement of both adrenals are seen. A, A longitudinal sonogram of the right adrenal shows linear echogenicity in the anterior part of the gland with a strong acoustic shadow posteriorly. B, On the computed tomography scan, the calcification appears to be more peripheral within the cortex of both adrenals.

Suprarenal Masses

Overview: Adrenal masses in the neonate are mainly caused by hemorrhage or neoplasm, particularly neuroblastoma. Extra-adrenal masses are rare with the most common being intra-abdominal pulmonary sequestration. An accurate diagnosis is of the utmost importance because of the different management for these entities. However, the diagnosis may be difficult because of overlapping imaging features and, therefore, may not be established on the initial imaging findings alone, often requiring follow-up imaging (mainly with ultrasonography), correlation with clinical history, and measurement of urine catecholamines. Because of the relatively good prognosis of perinatal neuroblastoma, an initial conservative management is warranted. CT and MRI have little role in the diagnosis of these lesions and are mainly indicated to assess extent and for staging of a suspected neuroblastoma.

Overview: Adrenal hemorrhage is the most common adrenal mass in neonates. It often occurs within the first few days of life but can occur prenatally and be seen on antenatal ultrasonography. It is more commonly right sided (70%) but may also be bilateral (10%).7 It usually occurs in situations of perinatal stress, including difficult or traumatic delivery, hypoxia, and sepsis. It may also occur in bleeding diatheses. Large infants and infants of mothers with diabetes are particularly susceptible. Adrenal hemorrhages in neonates may not infrequently be an incidental finding.

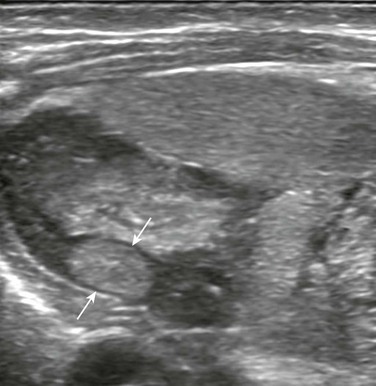

Imaging: Ultrasonography is the modality of choice for documentation of the presence of an adrenal hemorrhage and for follow-up. Ultrasonography shows a suprarenal mass of variable echogenicity (Fig. 122-7) without flow on color Doppler ultrasonography. These findings may overlap with those of neuroblastoma, and therefore, further confirmation of the diagnosis may be obtained from follow-up ultrasonography.7 The adrenal hemorrhage decreases in size and changes echogenicity within the first week (see Fig. 122-7), followed by development of peripheral increased echogenicity due to calcification. The calcification becomes more compacted as the mass becomes smaller, and the adrenal eventually resumes its more normal shape and size.

Figure 122-7 Adrenal hemorrhage detected in the third trimester of pregnancy in a neonate.

A, A longitudinal sonogram of the right upper quadrant at 17 days of age shows a multiseptated predominantly cystic mass (arrows) superior to the right kidney. No flow in the septa was evident on color Doppler interrogation (not shown). B, The follow-up sonogram at 38 days of age shows significant decrease in size of the mass (arrows) as well as a change in its echogenicity. The pattern of evolution of this lesion is compatible with an adrenal hemorrhage. In addition, urine catecholamines and metaiodobenzylguanidine scan were negative in this patient.

Neuroblastoma

Overview and Imaging: Neuroblastoma is the most common adrenal neoplasm found in the fetus on ultrasonography and in neonates.8 When detected antenatally, it is generally diagnosed in the third trimester. It is frequently right sided, may vary significantly in size (Fig. 122-8), and often has a more cystic appearance than in older infants and children (Fig. 122-9).8,9 However, the echogenicity on ultrasonography varies; some may be evenly echogenic (Fig. 122-10), whereas others are highly heterogeneous. Flow is often detected on color Doppler ultrasonography aiding in the differentiation from hemorrhage (see Fig. 122-10). However, the absence of flow does not exclude the diagnosis of neuroblastoma.

Figure 122-8 Left adrenal neuroblastoma found incidentally in a 13-day-old boy who had bladder perforation.

A longitudinal sonogram of the left upper quadrant shows a very small hyperechoic mass (arrows) within one of the limbs of the left adrenal.

Figure 122-9 Right adrenal neuroblastoma detected in the third trimester of pregnancy in an 8-day-old girl.

A longitudinal sonogram shows a complex, multiseptated, predominantly cystic mass (arrows) involving the right adrenal. No flow in the septa was evident on color Doppler interrogation (not shown). The mass has similar features to the adrenal hemorrhage illustrated in Figure 122-7, although in this case, urine catecholamines were elevated and the mass was metaiodobenzylguanidine avid.

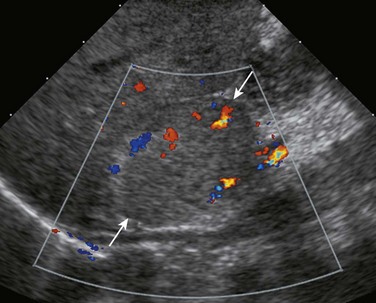

Figure 122-10 Right adrenal neuroblastoma detected in the third trimester of pregnancy in a 10-day-old boy.

A longitudinal sonogram shows a relatively homogenous hyperechoic mass (arrows) arising in a somewhat exophytic fashion from the inferior and anterior aspect of the right adrenal. Intralesional flow is shown on color Doppler interrogation.

Perinatal neuroblastoma also may present with metastatic disease, typically in the liver, skin, and bone marrow, corresponding to stage MS (equivalent to stage 4S of the formerly used International Neuroblastoma Staging System) (see Chapter 123). Diffuse infiltration of the liver may result in massive hepatomegaly (e-Fig. 122-11).

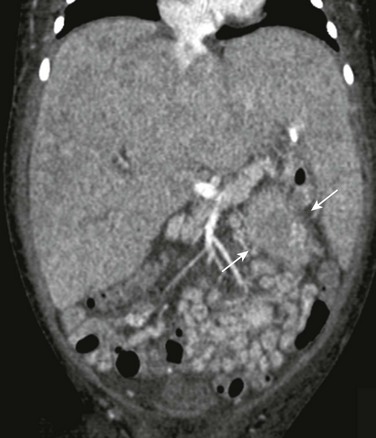

e-Figure 122-11 Bilateral adrenal neuroblastoma with liver metastatic disease.

Coronal reformatted computed tomography image shows marked hepatomegaly with heterogeneous attenuation of the parenchyma due to metastatic infiltration by neuroblastoma. Part of the left adrenal mass is evident (arrows).

In contrast to neuroblastoma in older children, in perinatal neuroblastoma urinary catecholamine metabolites are elevated in only 40% of cases, and metaiodobenzylguanidine avidity exists in only 70% of cases.8

Intra-abdominal Pulmonary Sequestration

Overview and Imaging: Intra-abdominal pulmonary sequestration is a mass of pulmonary tissue, separate from the lung, with systemic arterial supply, more commonly found in the suprarenal region, usually left sided. In contrast to adrenal neuroblastoma and hemorrhage, these are commonly diagnosed in the second trimester of pregnancy.10 In fact, a suprarenal mass diagnosed in the third trimester of pregnancy but with a normal second trimester sonogram militates against a sequestration. On ultrasonography, sequestrations appear homogeneously hyperechoic, although in more than half the cases, small (<5 mm), well-defined intralesional cysts exist because of the presence of associated congenital pulmonary airway malformation (Fig. 122-12).10,11 The normal adrenal gland is often identified, displaced anteriorly by the sequestration. These sequestrations may significantly decrease in size and even disappear on follow-up ultrasonography.11

Balassy, C, Navarro, OM, Daneman, A. Adrenal masses in children. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49(4):711–727.

Paterson, A. Adrenal pathology in childhood: a spectrum of disease. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2491–2508.

Rosado-de-Christenson, ML, Frazier, AA, Stocker, JT, et al. Extralobar sequestration: radiologic-pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 1993;13:425–441.

References

1. Rosenberg, ER, Bowie, JO, Andreotti, RF, et al. Sonographic evaluation of fetal adrenal glands. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;139:1145–1147.

2. Koplewitz, BZ, Daneman, A, Cutz, E, et al. Neonatal adrenal congestion: a sonographic-pathologic correlation. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:958–962.

3. Al-Allwan, I, Navarro, O, Daneman, D, et al. Clinical utility of adrenal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J Pediatr. 1999;135:71–75.

4. Hoffman, CK, Filly, RA, Callen, PW. The “lying down” adrenal sign: a sonographic indicator of renal agenesis or ectopia in fetuses and neonates. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:533–536.

5. Strouse, PJ, Haller, JO, Berdon, WE, et al. Horseshoe adrenal gland in association with asplenia: presentation of six new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:778–782.

6. Özmen, MN, Aygün, N, Kiliç, I, et al. Wolman’s disease: ultrasonographic and computed tomographic findings. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:541–542.

7. Deeg, KH, Bettendorf, U, Hofmann, V. Differential diagnosis of neonatal adrenal haemorrhage and congenital neuroblastoma by colour coded Doppler sonography and power Doppler sonography. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157:294–297.

8. Nuchtern, JG. Perinatal neuroblastoma. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15:10–16.

9. Forman, HP, Leonidas, JC, Berdon, WE, et al. Congenital neuroblastoma: evaluation with multimodality imaging. Radiology. 1990;175:365–368.

10. Curtis, MR, Mooney, DP, Vaccaro, TJ, et al. Prenatal ultrasound characterization of the suprarenal mass: the distinction between neuroblastoma and subdiaphragmatic extralobar pulmonary sequestration. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:75–83.

11. Daneman, A, Baunin, C, Lobo, E, et al. Disappearing suprarenal masses in fetuses and infants. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:675–681.