Congenital and Neonatal Abnormalities

Kidney and Ureter

Overview, Etiology, and Clinical Presentation: A multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) is the most common form of cystic renal dysplasia. With high-grade obstruction or atresia of the upper urinary tract (renal pelvis and/or ureter) during early renogenesis, disordered parenchymal development results in an MCDK.1 Two types of MCDK exist: the pelvoinfundibular type (common) and the hydronephrotic type (uncommon).2,3 MCDK can occur in half of a duplex kidney (usually the upper moiety) or in renal fusion anomalies, such as a horseshoe kidney and crossed fused renal ectopia. MCDK is sporadic in most cases, although familial cases have been described.1,4 Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) (both ipsilateral and contralateral) and contralateral ureteropelvic junction obstruction are common.1,5 Long-term sequelae (e.g., infection and hypertension) are rare, because most affected kidneys either partially or completely involute on their own over time.6–9

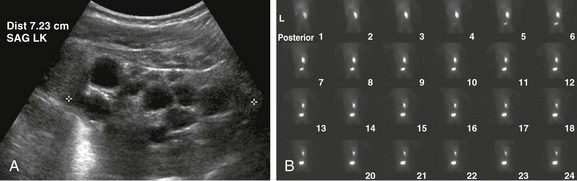

Imaging: On ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a classic MCDK is characterized by multiple cysts of various sizes (ranging from 1 mm to several cm) that do not communicate, with no normal intervening renal parenchyma (Fig. 114-1). The affected kidney may be small, normal, or enlarged.1 Compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral kidney often is present.10 The hydronephrotic form has cysts that communicate, mimicking pelvocaliectasis, but no normal functioning renal tissue.2 The diagnosis of both classic and hydronephrotic MCDK can be confirmed by diuretic renal scintigraphy (e-Fig. 114-2) or MR urography (MRU) (e-Fig. 114-3). A voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) may reveal VUR into a blind-ending ureter on the side of the MCDK.11,12

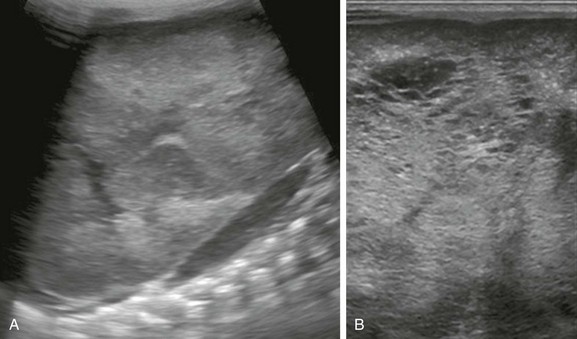

Figure 114-1 A multicystic dysplastic kidney in a 3-month-old boy.

A longitudinal ultrasound image of an enlarged left kidney shows multiple noncommunicating simple cysts of variable size, mimicking hydronephrosis. The very small amount of remaining renal parenchyma is abnormally echogenic.

e-Figure 114-2 A multicystic dysplastic kidney in a 6 month-old boy.

A, A longitudinal ultrasound image of the left kidney shows multiple noncommunicating cysts of variable size. Visualized renal parenchyma is abnormally echogenic. B, Posterior diuretic renal scintigraphy images show no appreciable left kidney function with no uptake or excretion of radiotracer. Right kidney function is normal.

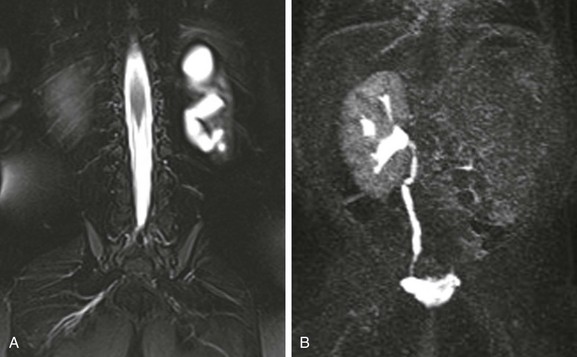

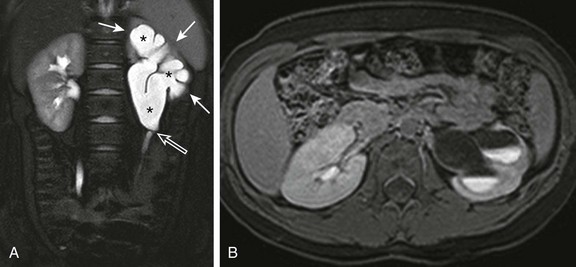

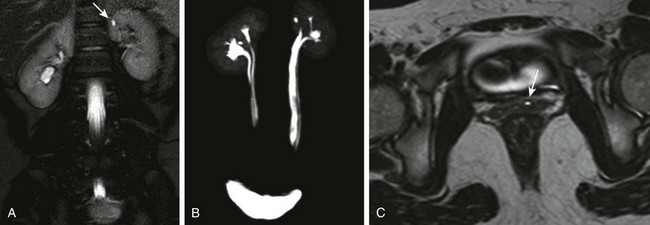

e-Figure 114-3 A multicystic dysplastic kidney and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, hydronephrotic form.

A, A coronal T2-weighted MR image with fat saturation shows a fluid signal within the left kidney that has a configuration similar to that of the renal collecting system. Only a small amount of left kidney parenchyma is present. B, A coronal T1-weighted MR urogram maximum intensity projection image obtained 15 minutes after contrast material injection confirms the absence of the left kidney function. The right kidney is normal.

Treatment: Follow-up ultrasound typically demonstrates involution of the cysts over time, eventually resulting in remnant dysplastic renal tissue that may be impossible to visualize.13,14 Immediate resection of an MCDK is rarely indicated15 and is reserved for cases in which the size of the kidney is a problem. In the past, routine nephrectomies were performed because of a fear of malignant degeneration. Current belief discounts this possibility, and as long as no other complication exists, surgery is not indicated.

Autosomal-Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

Overview and Etiology: Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), the most common form of inherited renal cystic disease, is seen in 1 in 800 live births.16,17 Two types of ADPKD exist, each with clearly defined chromosomal mutations. The more severe form (PKD1) accounts for about 85% to 90% of cases, whereas the milder phenotype (PKD2) presents later in life, results in less morbidity, and is less common.16,18 Cysts arise from both the renal cortex and the medulla.16,19

Clinical Presentation: Systemic hypertension, hematuria, and slowly progressive renal insufficiency are the typical clinical manifestations.1,20 ADPKD is very rarely detected prenatally because fewer than 5% of nephrons are cystic before birth.1 Diagnosis of ADPKD early in life portends a poor prognosis; 43% of affected persons die in the first year of life, hypertension develops in 67%, and some affected children progress rapidly to end-stage renal disease.20 Because it can be difficult to delineate between autosomal-recessive and autosomal-dominant forms of polycystic kidney disease in a neonate, screening of siblings and parents may be helpful.

Imaging: The diagnosis of ADPKD usually is made on the basis of ultrasound (Fig. 114-4), although CT or MRI also can suggest it. Although the kidneys may be normal during the first decade of life, they also may contain one or more simple cysts (Fig. 114-5).16,21 The kidneys may be abnormally enlarged and echogenic, mimicking autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) in early life (e-Fig. 114-6).16,22 Although it is typically a bilateral process, imaging findings may be asymmetric, and in young children they can manifest as a unilateral abnormality.16,21,23 Microscopic cysts, as well as larger cysts that can be detected by cross-sectional imaging techniques, are common in the liver and less frequent in the pancreas, spleen, lungs, thyroid, ovaries, and testes.19 The remainder of the urinary tract is usually normal.

Figure 114-4 Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in a newborn.

A longitudinal ultrasound image shows a small lower pole simple renal cyst (arrow). The renal cortex appears echogenic as well. Three additional simple renal cysts were identified in this neonate with a maternal history of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Figure 114-5 Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in an 8-year-old girl.

A coronal reformatted contrast-enhanced computed tomography image shows multiple low attenuation lesions in both kidneys due to the presence of cysts.

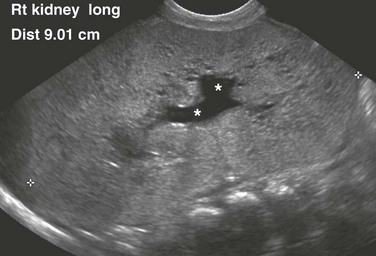

e-Figure 114-6 Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) in a neonate mimicking autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD).

A longitudinal ultrasound image shows a markedly enlarged echogenic kidney with loss of corticomedullary differentiation. Multiple tiny cystic spaces are present within the kidney. Mild pelvocaliectasis (asterisks) is present as well. Although the imaging features favor ARPKD, a maternal history of ADPKD led to disease.

Treatment: Although renal function is generally maintained during childhood, ADPKD is responsible for the need for chronic dialysis in 10% to 12% of adult patients.1 Hypertension should be managed medically to prevent long-term complications. About 12% to 15% of patients with ADPKD have an intracranial aneurysm, most often arising from the circle of Willis.19,23–25 Screening MR angiography usually is not performed in childhood, however, because aneurysm rupture is rare in this period.

Autosomal-Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease

Overview: ARPKD is a rare disorder (occurring in 1 : 20,000 live births) that affects both kidneys.26,27 Genetic studies have localized the inheritance of ARPKD to chromosome 6p.27,28 The PKHD1 gene is expressed in fetal and adult kidneys and livers, the two major sites affected by the disease.28 Approximately 1 in 70 persons are a carrier for this condition.26,27

Clinical Presentation: ARPKD has been subdivided into categories based on clinical presentation. The perinatal and neonatal forms, which have the poorest prognosis, are associated with severe renal dysfunction and minimal hepatic portal tract fibrosis. Affected children often die of the disease early in life.27,29 Infantile and juvenile forms are associated with less severe renal dysfunction and more significant hepatic fibrosis.27 The degrees of renal and hepatic abnormalities tend to be inversely proportional.17,27 A number of children with ARPKD also have Caroli disease (see Chapter 88).27

Pathology: Histologically, the kidneys have a spongelike appearance, replaced by myriad minute 1- to 2-mm cysts of relatively uniform size, representing markedly dilated and elongated collecting ducts.1,27 These cysts radiate from the hilum to the surface of the kidney without a clear demarcation between the medulla and cortex. Fibrosis is present in the renal interstitium. Children with significant hepatic involvement are at increased risk for complications related to portal hypertension, and ascending cholangitis can lead to sepsis and death.27

Imaging: Abdominal radiography in the neonatal period commonly reveals bilateral abdominal or flank masses with centralized gas-filled bowel loops. The lungs may appear small because of a combination of pulmonary hypoplasia and mass effect from marked nephromegaly (e-Fig. 114-7).27

e-Figure 114-7 Autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease in a newborn boy.

An anteroposterior chest radiograph shows small lungs due to pulmonary hypoplasia. Bulging of the flanks and centralization of bowel gas is due to bilateral nephromegaly.

On ultrasound, affected neonatal kidneys tend to be smoothly enlarged (frequently more than four standard deviations above the mean expected length for age), are hyperechoic as a result of the multiple acoustic interfaces at the walls of the dilated ducts, and have poor corticomedullary differentiation (e-Fig. 114-8).1,27,29,30 On occasion, discrete cysts (solitary or multiple) of variable size (most commonly <1 cm) may be seen (Fig. 114-9).26,30 A sonolucent rim may be seen at the periphery of the kidney, especially in older infants, as a result of cortical compression and relative sparing.26,27 Contrast-enhanced CT (Fig. 114-10) or MRI show delayed opacification of the renal parenchyma with a prolonged and striated nephrogram. When studied with MRI, the dilated tubules in affected kidneys appear linear and hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging, radiating from the medulla toward the cortex (Fig. 114-11).31

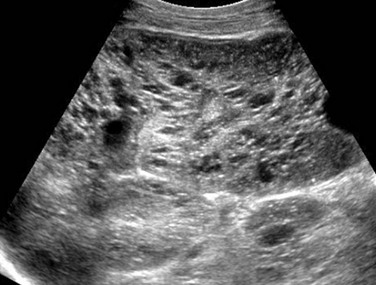

Figure 114-9 Autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease in a 6-month-old boy presenting with acute renal failure and bilateral renal masses.

A longitudinal ultrasound image of the right kidney shows nephromegaly, loss of normal corticomedullary differentiation, and innumerable tiny cystic structures replacing the renal parenchyma.

Figure 114-10 Autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease.

A computed tomography image shows that the pathologic process is primarily medullary. The dilated tubules have produced a linear pattern that can be seen clearly in a few regions. Marked cortical thinning present along the anterior aspect of each kidney is not a typical finding, because the cortex is usually spared.

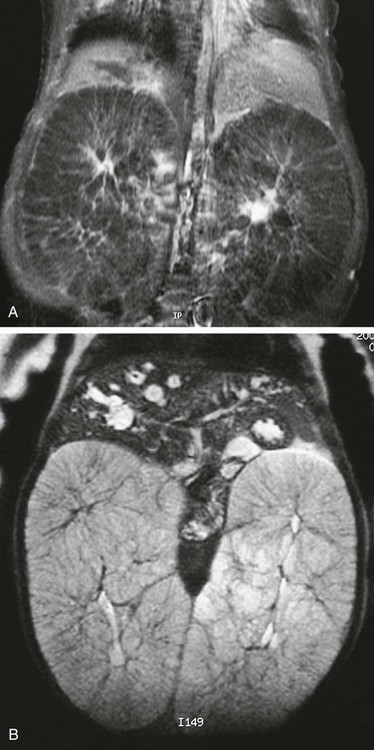

Figure 114-11 Autosomal-recessive polycystic disease.

T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) magnetic resonance images of an infant with autosomal-recessive polycystic disease. The kidneys are enormously enlarged, and on the T1-weighted image, the spoke wheel is appreciated. The patient also has Caroli disease as seen by the dilated biliary system on the T2-weighted image.

e-Figure 114-8 Autosomal-recessive polycystic kidney disease in a newborn girl.

A, A longitudinal ultrasound image of the left kidney confirms the presence of a nephromegaly with loss of corticomedullary differentiation. B, Further assessment of the kidney using a linear high-frequency transducer reveals numerous tiny cystic structures within the kidney due to dilated ducts and tubules. The peripheral cortex is relatively hypoechoic.

Treatment: Eighty-six percent of patients who survive beyond 1 month of age are alive at 1 year, and 67% are alive at 15 years.32 In infants who have initially adequate (although not normal) renal function, the disease may not be detected until later in the first decade, when ultrasound is being performed for unrelated purposes. Systemic renovascular hypertension may occur and require medical management.17,27 Persons with ARPKD who have severely impaired renal function eventually will require renal replacement therapy, either dialysis or renal transplantation.

Other Renal Cystic Diseases in Children

Many rare inherited syndromes and genetic disorders are associated with renal cystic disease (Box 114-1).

Calyceal Diverticulum

Overview, Etiology, and Clinical Presentation: A calyceal diverticulum represents a focal outpouching of the renal collecting system that is located within the renal parenchyma and that contains urine.33 This condition has an incidence of 3.3-4.5 : 1000 in children, based on excretory urography.34–36 Calyceal diverticula are likely developmental in origin; they are lined with urothelium and surrounded by muscularis mucosa.33,35 Although these structures most commonly are an incidental finding, they can be associated with both infection and calculus formation as a result of urinary stasis.33,35,37

Imaging: Abdominal radiographs may be normal or may demonstrate one or more calculi (or milk of calcium) within a calyceal diverticulum.35 Upon ultrasound, such diverticula may mimic a solitary renal cyst, appearing as a round, thin-walled anechoic structure (Fig. 114-12).34 They can vary in size ranging from a few millimeters to several centimeters (with a mean size around 11 mm).35,37 They most commonly occur within the upper pole of the kidney.33 Upon excretory phase imaging (including excretory urography, MRI, and CT), calyceal diverticula typically fill with contrast material (Fig. 114-13). A thin connection, or neck, to an adjacent calyceal fornix may or may not be identified.35

Figure 114-12 Calyceal diverticulum.

A longitudinal ultrasound image reveals a medullary cyst (arrows). On a subsequent intravenous urography procedure, the cyst filled with contrast material.

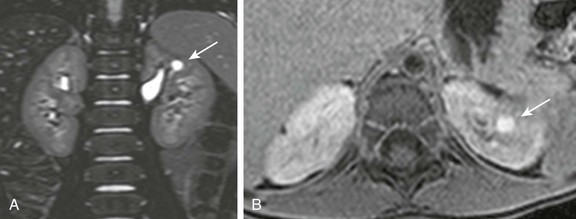

Figure 114-13 Calyceal diverticulum in a 4-year-old girl.

A, A coronal three-dimensional T2-weighted fast spin echo magnetic resonance (MR) image with fat saturation shows a round structure within the upper pole of the left kidney demonstrating signal intensity identical to urine. B, An axial delayed postcontrast T1-weighted MR image with fat saturation reveals excreted contrast material filling this abnormality.

Congenital Infundibulopelvic Stenosis

Overview, Etiology, and Clinical Presentation: Congenital infundibulopelvic stenosis is a very rare congenital anomaly of the renal collecting system that presents as unilateral or bilateral caliectasis. Although the exact etiology of this condition is uncertain, Lucaya et al.39 hypothesized that this abnormality is a milder manifestation of the process that results in multicystic dysplastic kidney. Affected children may be predisposed to urinary tract infections, and this condition may be associated with other renal and urinary tract anomalies.39

Imaging: Upon contrast-enhanced excretory phase imaging studies (including excretory urography, MRU, and CT), this condition has a specific appearance: the renal collecting system infundibula are abnormally narrowed but not entirely obliterated, and the calyces appear abnormally rounded and dilated (Fig. 114-14). The renal pelvis also appears narrowed as a result of stenosis or hypoplasia. This condition may be unilateral or bilateral. Despite the cystlike appearance of the calyces on such contrast-enhanced studies, the ultrasound appearance of the kidneys can be normal. Renal function may be normal to severely impaired.39

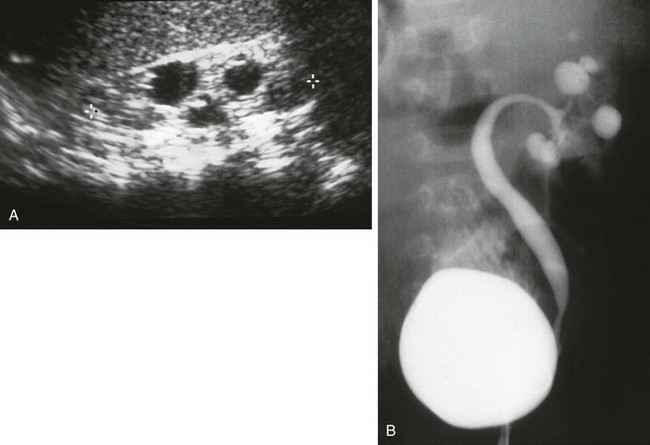

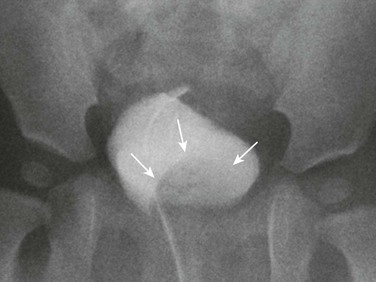

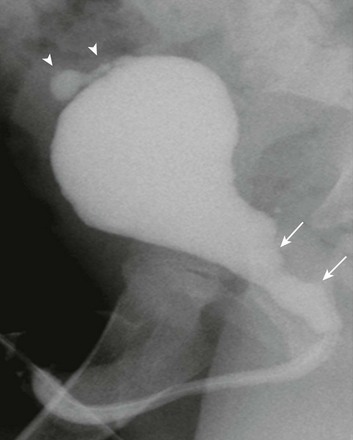

Figure 114-14 Infundibulopelvic stenosis simulating cystic kidney disease.

A, A longitudinal ultrasound image shows multiple “cysts” scattered throughout the kidney in this child with VACTERL association. B, A voiding cystourethrogram shows vesicoureteral reflux into the abnormal pelvocalyceal system. The ureter has a greater caliber than the renal pelvis, infundibula, and calyces. The most peripheral portion of each calyx is rounded, producing the cystic spaces seen with ultrasound.

Congenital Megacalyces (Megacalycosis)

Overview, Etiology, and Clinical Presentation: Congenital megacalyces is a very rare anomaly of the renal collecting system that may be easily confused for hydronephrosis.40 Calyceal involvement may be unilateral or bilateral. This abnormal calyceal dilatation is not due to urinary tract obstruction but instead is likely a result of underdevelopment/hypoplasia of the renal medullary pyramids.41,42 Boys are more commonly affected than are girls. Associated urinary stasis may predispose affected children to urinary tract infection and urolithiasis.41

Imaging: Congenital megacalyces may be misidentified as obstructive caliectasis by ultrasound. With excretory urography, however, this condition is easily identifiable because of the presence of abnormally dilated calyces that lack normal papillary impressions, have a polygonal or faceted shape, and appear to be increased in number (20 or more calyces may be seen) (Fig. 114-15).42 The renal parenchyma overlying affected calyces may appear thin. The renal pelvis can be normal in caliber or mildly dilated,41 and classically, no related urinary tract obstruction should be present. This appearance of the calyces on MRU and excretory-phase CT (CT urography) also should suggest the diagnosis.

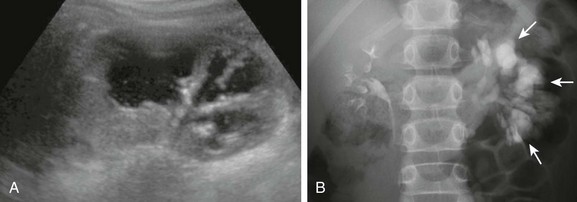

Figure 114-15 Congenital megacalyces in a 6-year-old boy.

A, A longitudinal ultrasound image shows multiple dilated calyces with overlying parenchymal thinning. Debris within the renal collecting system was due to infection. B, A subsequent excretory urography image demonstrates contrast material filling an increased number of left kidney polygon-shaped calyces (arrows), confirming the diagnosis of congenital megacalyces.

Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction

Overview: Ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction is the most common type of congenital urinary tract obstruction, occurring in 3 per 1000 live births. Boys are more frequently affected than are girls, and the left kidney is more commonly involved than the right kidney. About 30% of cases are bilateral, although severity of obstruction and pelvocaliectasis may be asymmetric.1

Pathophysiology: An intrinsic narrowing (e.g., smooth muscle deficiency, increased fibrosis and collagen, stricture, valve, kinking, and altered peristalsis) occurs at the level of the UPJ, leading to dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system.1,43 On occasion, extrinsic narrowing can be seen from a crossing renal vessel in older children and adults.44 UPJ obstruction often is seen in association with other urinary tract anomalies, such as contralateral multicystic dysplastic kidney, upper urinary tract duplication,45,46 VUR,47 and ureterovesical junction obstruction.48

Clinical Presentation: When UPJ obstruction is not detected prenatally, affected children commonly present with a palpable abdominal mass in the neonatal period. Older children may present with intermittent hydronephrosis and flank pain, often associated with crossing vessels. UPJ obstruction can be complicated by calculi, infection (pyonephrosis), and hemorrhage, especially when diagnosis is delayed.29

Imaging: On ultrasound, abnormal dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system of varying degrees is seen, whereas the ureter is normal in caliber.1,29 Ultrasound findings suggestive of renal dysplasia may be present in cases of severe obstruction (described later). Debris within the collecting system can represent infection or hemorrhage (Fig. 114-16). Careful interrogation of the UPJ region with Doppler ultrasound may identify a crossing vessel, when present.49 Frequently, separating dilated nonobstructed from dilated obstructed renal collecting systems is difficult by ultrasound alone.

Figure 114-16 Ureteropelvic junction obstruction in a newborn boy with a typical ultrasound appearance.

A longitudinal image of the left kidney shows moderate to severe dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system (asterisks), with the renal pelvis being more dilated that the calyces. The proximal ureter could not be seen. Debris is present in the renal pelvis.

Abdominal radiographs may show soft tissue fullness, bulging of the flank, and displacement of bowel loops from the affected side (e-Fig. 114-17). On contrast-enhanced excretory phase CT, the obstructed kidney demonstrates delayed opacification and excretion of contrast material.43 CT angiography with multiplanar reformatted and three-dimensional images may be used to depict suspected crossing vessels as a cause of UPJ obstruction in older children and adults.50

e-Figure 114-17 Ureteropelvic junction obstruction.

An abdominal radiograph reveals mass effect in the central and left abdomen, displacing bowel to the right.

Diuretic renal scintigraphy is commonly used to evaluate UPJ obstruction; both renal function (including perfusion and differential function) and drainage are evaluated (e-Fig. 114-18).51,52 MRU is an increasingly important tool in the evaluation of untreated and treated UPJ obstructions.53 This imaging technique currently allows for the detailed assessment of urinary tract anatomy, while also providing information regarding renal function, including differential renal function, and the presence or absence of obstructive uropathy (Fig. 114-19).53–55 Both a retrograde pyelogram and a antegrade nephrostogram also can be performed to establish the level of upper urinary tract obstruction, if clinically necessary.

Figure 114-19 Ureteropelvic junction obstruction in a 9-year-old girl.

A, A coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image with fat saturation shows moderate to severe left pelvocaliectasis (asterisks) with overlying parenchymal thinning (white arrows). The left ureter is normal in caliber, and there is apparent kinking of the left ureteropelvic junction (open arrow). B, A postfurosemide axial T1-weighted MR image with fat saturation obtained 20 minutes after intravenous contrast material injection confirms left obstructive uropathy. Only a small amount of contrast material is present in the left collecting system, and multiple urine-contrast levels are present as a result of stasis. Because a substantial amount of enhancing left renal parenchyma was seen, the patient was treated with surgical pyeloplasty to preserve renal function.

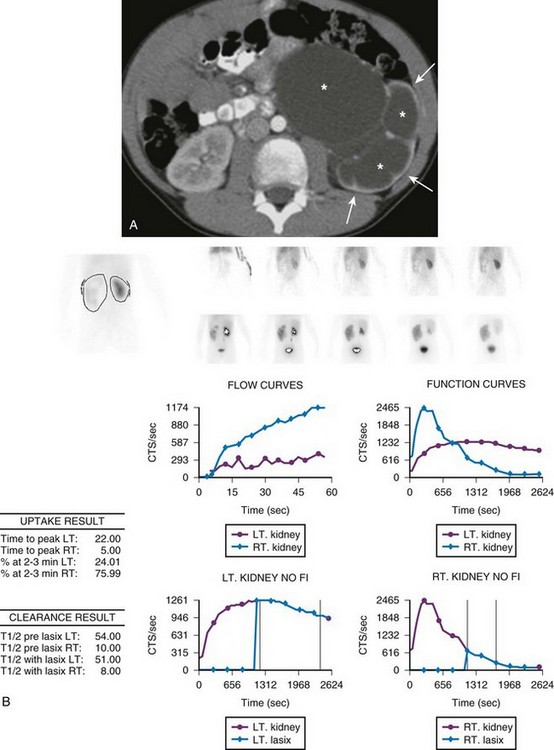

e-Figure 114-18 Ureteropelvic junction obstruction in a 7-year-old with gross hematuria after a fall.

A, An axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography image demonstrates marked left pelvocaliectasis (asterisks) and renal parenchymal thinning (arrows). The left ureter was normal in caliber. B, Diuretic renal scintigraphy demonstrates decreased perfusion of the left kidney. The left kidney shows substantially delayed uptake and excretion of radiotracer despite intravenous furosemide administration, a pattern consistent with obstruction. CTS, Counts; LT, left; RT, right.

Treatment: Recent literature has emphasized the conservative management of neonates with UPJ obstruction, especially with preserved renal function shown by biochemical parameters and renal scintigraphy.1,56–58 A substantial number of cases that are identified prenatally resolve spontaneously without requiring surgery.56–58 Indications for surgery include reduced renal function, sustained increase in pelvicalyceal dilation, breakthrough infections, a solitary kidney, and severe bilateral hydronephrosis.58,59 Treatment, if deemed necessary, usually is accomplished with a dismembered pyeloplasty.1

Upper Urinary Tract Duplication

Overview and Etiology: A duplex kidney consists of a single renal unit that is drained by two collecting systems. If two ureteric buds are present or the ureteric bud bifurcates before meeting the metanephric blastema, duplication of the renal collecting system and ureter occur.60 Possibilities include a simple bifid renal pelvis, a bifid ureter (i.e., incomplete ureteral duplication), complete ureteral duplication, an ectopic ureter, and an ectopic ureterocele. Incomplete duplication of the upper urinary tract is more common than is complete duplication. Even when two ureters are present distally, they frequently enter the bladder via a common sheath.

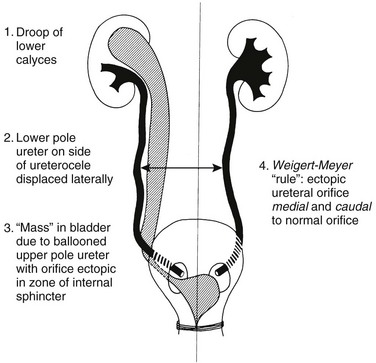

In cases of complete ureteral duplication, one ureter takes up a near-normal position within the urinary bladder, and the other moves inferiorly with the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct into an abnormal location (e.g., the bladder neck, urethra, vagina, or perineum in girls or the ejaculatory system in boys).60 The Weigert-Meyer rule, which is applied only to complete duplications, states that the ureter that drains the upper moiety inserts inferior and medial to the lower moiety ureter (Fig. 114-20). In addition, the ectopic ureter is more likely to be obstructed, whereas the lower moiety ureter is more likely to reflux. Extravesical ureter insertion is far more common in girls than in boys. Extravesical ureter insertions in boys are almost always above the sphincter mechanism; they can be below the sphincter mechanism in girls and present with urinary dribbling and daytime and nighttime wetness. On occasion, ectopic ureteroceles may be detected in the setting of a diminutive pelvicalyceal system, the so-called “ureterocele disproportion.”60,61

Clinical Presentation: Clinically, incomplete duplication of the upper urinary tract may be asymptomatic or may present with urinary tract infections as a result of ureteroureteral reflux and stasis (so-called “yo-yo” reflux).60 Children with complete duplication may present in a variety of manners, including hydronephrosis, urinary tract infection, and bladder outlet obstruction due to a large ureterocele.60,62 Complete duplications in girls also may present with enuresis (both daytime and nocturnal wetness) as a result of insertion of the ectopic ureter into the urethra below the level of the sphincter mechanism or vagina.60

Imaging: Ultrasound may identify a prominent renal parenchymal column that appears to separate the sinus fat, providing indirect evidence of collecting system duplication (Fig. 114-21). More commonly, complete duplications present with upper moiety hydronephrosis. Dilatation of the lower moiety can be due to VUR or, less often, concomitant UPJ obstruction (e-Fig. 114-22).45,60 Ultrasound of the urinary bladder may show a thin-walled intraluminal cystic structure, consistent with a ureterocele (Fig. 114-23).1 Ureteroceles can vary in size and may appear septated or multiloculated, and when they are located in the midline, it may be difficult to establish the exact side from which they arise.62

Figure 114-21 Upper urinary tract duplication in a 6-week-old girl.

A longitudinal ultrasound image through the left kidney shows separate abnormally dilated upper and lower moiety collecting systems. Thinning of overlying renal parenchyma is seen.

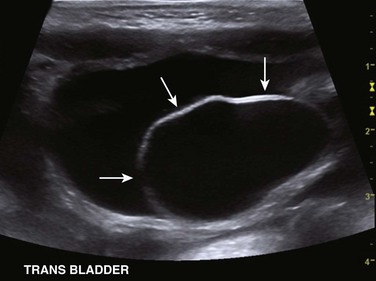

Figure 114-23 Upper urinary tract duplication in a 6-week-old girl.

A transverse ultrasound image through the bladder confirms the presence of a large left ureterocele (arrows).

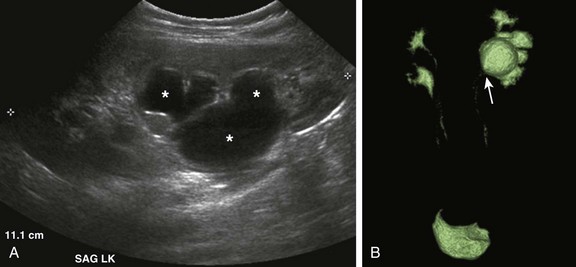

e-Figure 114-22 Bilateral upper urinary tract duplication and left lower moiety ureteropelvic junction obstruction in a 6-year-old girl.

A, A longitudinal ultrasound image of the left kidney demonstrates moderate pelvocaliectasis (asterisks) of uncertain etiology. A voiding cystourethrogram showed no vesicoureteral reflux. B, A contrast-enhanced MR urogram volume-rendered image confirms duplication of the bilateral upper urinary tracts. The left lower moiety collecting system is hydronephrotic and is obstructed at the level of the ureteropelvic junction (arrow).

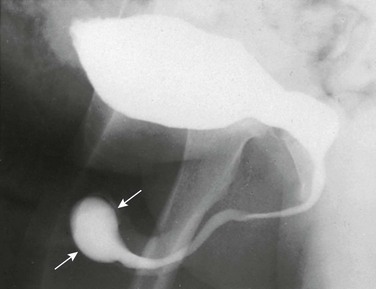

In the early bladder filling phase of a VCUG examination, a smooth round filling defect is observed, consistent with a ureterocele (Fig. 114-24). Ureteroceles become more difficult to visualize as the urinary bladder distends with contrast material because of obscuration, flattening, or even eversion.60,62 VUR into the lower moiety collecting system of a duplex kidney commonly reveals too few calyces and has a “drooping lily” appearance as a result of abnormal long-axis orientation (Fig. 114-25).60 The normal long axis of the renal collecting system should parallel that of the ipsilateral psoas muscle. On occasion, VUR may be noted involving the upper moiety of a duplicated system (in about 11% of children), sometimes only after ureterocele incision.60,63 VUR also can be used to discriminate incomplete from complete ureteral duplications (Fig. 114-26).

Figure 114-24 Left upper urinary tract duplication in a 1-year-old girl.

A voiding cystourethrogram image demonstrates a large urinary bladder-filling defect (arrows), consistent with a ureterocele. No vesicoureteral reflux was visualized.

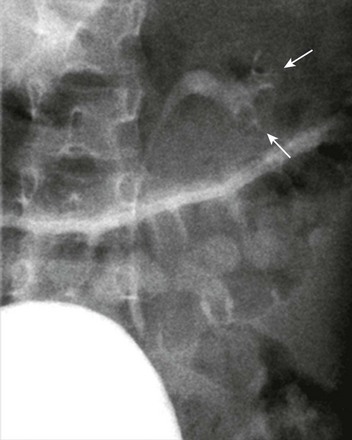

Figure 114-25 Left upper urinary tract duplication in a 6-year-old girl.

A voiding cystourethrogram image shows left grade 2 vesicoureteral reflux. The left renal collecting system has too few calyces and its axis is abnormally oriented, giving rise to the “drooping lily” appearance (arrows).

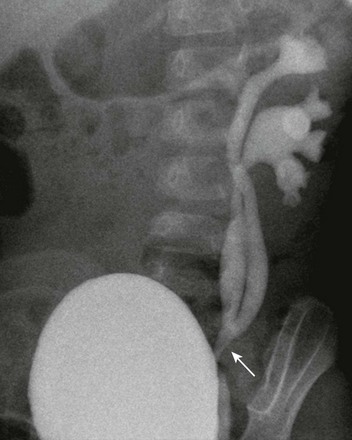

Figure 114-26 Incomplete duplication of the left upper urinary tract in a 1-year-old girl.

A voiding cystourethrogram image shows reflux of contrast material into two separate left renal collecting systems and proximal/mid ureters. The ureters join distally (arrow), above the left ureterovesical junction.

MRI (particularly MRU) provides a precise assessment of duplicated upper urinary tract anatomy (e-Fig. 114-27). A variety of T2-weighted imaging techniques can be used to image urine-filled structures, even in the setting of obstruction. MRU also allows for the assessment of renal function and the presence of obstructive uropathy and is optimal for the assessment of the extravesical ureteric insertions (e-Fig. 114-28).60,64

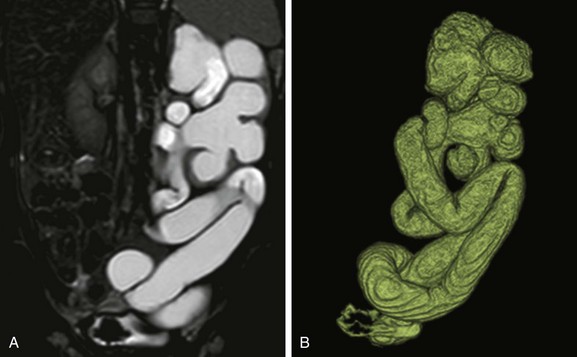

e-Figure 114-27 Left upper urinary tract duplication in a 1-year-old girl.

A, A coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image shows marked left kidney hydroureteronephrosis and left renal parenchymal thinning. B, A three-dimensional T2-weighted MR urogram volume-rendered image confirms the presence of left upper urinary tract duplication with marked dilatation and tortuosity of the both the upper and lower moiety upper tracts.

e-Figure 114-28 Upper urinary tract duplication and an ectopic ureter in a 10-year-old girl.

A, A coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image shows an apparent tiny renal cyst (arrow) in the upper pole of the left kidney. B, A three-dimensional (3D) T2-weighted MR urogram maximum intensity projection image confirms the presence of bilateral upper urinary tract duplication. The left upper moiety renal collecting system consists of a single rudimentary calyx. The distal ureters are not well visualized. C, A high-resolution axial 3D T2-weighted fast spin echo MR image through the lower pelvis shows the left upper moiety ectopic ureter (arrow) located in the anterior wall of the vagina. The ureter drained into the lower urethra just above the vaginal introitus.

Treatment: Incomplete duplications of the upper urinary tract are frequently asymptomatic and require no specific treatment. Specific treatments for upper moiety obstruction include endoscopic puncture or excision of an obstructing ureterocele, ureteroureterostomy, and upper moiety heminephrectomy in the setting of poor or absent function.60,65,66 Lower moiety dilatation due to VUR may require ureteral reimplantation, whereas dilatation due to UPJ obstruction may require surgical pyeloplasty. Multicystic dysplastic upper moieties commonly involute over time without the need for surgical intervention.67

Urinary Bladder

Prune-Belly Syndrome (Eagle-Barrett Syndrome)

Overview, Etiology, and Clinical Presentation: Prune-belly syndrome, also known as Eagle-Barrett or triad syndrome, includes the constellation of bilateral cryptorchidism, anterior abdominal wall muscular deficiency, and a variety of urinary tract anomalies, including megacystis and hydroureteronephrosis.68,69 The appearance of the abdominal wall on physical examination and radiographs has a characteristic appearance. Although the pathogenesis of prune-belly syndrome is controversial, two main theories are currently suggested: (1) bladder outlet obstruction early in utero and (2) a primary mesodermal defect.68–70 This condition is usually nonhereditary (although familial cases have been reported), almost always affects boys (3% to 5% of cases occur in girls), and is present in 1 : 29,000 to 1 : 50,000 live births.68,69 Associated anomalies of the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and gastrointestinal systems also may be present.

Imaging: On physical examination and radiographs, the abdominal wall of affected neonates has a characteristic wrinkled appearance with bulging of the flanks resulting from muscular deficiency (e-Fig. 114-29). VCUG allows depiction of the urinary bladder and urethral anatomy, identifies VUR, and determines whether a urachal anomaly is present. Markedly dilated, tortuous ureters are common because of a combination of muscular deficiency and VUR, which is present in approximately 75% of patients with prune-belly syndrome (Fig. 114-30).69 Upper urinary tract obstruction typically is not present. The urinary bladder usually has a smooth wall, increased capacity (megacystis), and may contain multiple diverticula. Urethral findings include dilatation and elongation of the prostatic urethra (e-Fig. 114-31), an enlarged utricle, megalourethra (e-Fig. 114-32), and rarely urethral atresia.68 A minority of patients with prune-belly syndrome have urethral obstruction due to an obstructing membrane or valve.68 The primary role of ultrasound in the neonatal period is to establish the status of the kidneys. The kidneys commonly show findings compatible with renal dysplasia, including small size, abnormally increased parenchymal echogenicity, loss of corticomedullary differentiation, and cortical cysts.

Figure 114-30 A neonatal boy with prune-belly syndrome.

A, An abdominal radiograph shows laxity of the anterior abdominal wall and bulging flanks. B, A longitudinal ultrasound image of the left kidney shows dilatation of the collecting system and proximal ureter. The kidney demonstrates abnormally increased parenchymal echogenicity and contains a few subcortical cysts (not shown), suggestive of renal dysplasia. C, A voiding cystourethrogram demonstrates dilatation of the posterior urethra (arrow) and high-grade vesicoureteric reflux (asterisks).

e-Figure 114-29 Prune-belly syndrome in a newborn boy.

The testes were undescended, and flank masses representing huge ureters were easily palpated.

e-Figure 114-31 Prune-belly syndrome.

An oblique voiding cystourethrogram image shows abnormal dilatation of the posterior urethra (arrows) that is likely due to prostatic hypoplasia. A contrast material–filled outpouching from the urinary bladder dome is consistent with a urachal diverticulum (arrowheads). No evidence of posterior urethral valves or urethral obstruction was seen.

Treatment: Children with prune-belly syndrome may require multiple surgical procedures. The testes should be relocated from the abdomen to the scrotum (orchiopexy) to minimize the risk of future testicular torsion and neoplasm.68 Urethral obstruction, if present, should be surgically addressed. VUR and poor upper urinary tract drainage may be managed with chronic antibiotic prophylaxis (which is currently preferred) or surgical reimplantation of the ureters to attempt to preserve renal function. Megacystis and poor urinary bladder emptying may be treated with reduction cystoplasty or vesicostomy.71 In more severe cases, anterior abdominal wall surgical reconstruction (abdominoplasty) is performed and may improve urinary bladder emptying.68,71 Because of chronic kidney disease and frequent underlying renal dysplasia, affected children eventually may require renal transplantation or dialysis therapy.

Megacystis-Microcolon-Intestinal Hypoperistalsis-Malrotation Syndrome

Overview, Etiology, and Clinical Presentation: The name “megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis-malrotation syndrome” actually describes the pertinent clinical and radiologic findings. Features of this syndrome may overlap with prune-belly syndrome. This syndrome is an autosomal-recessive disorder seen mostly in girls. It presents clinically with severe abdominal distention during the neonatal period because of functional bowel obstruction and severe urinary bladder distention.72,73

Imaging: Abdominal radiography may demonstrate a large, round mass emanating from the pelvis because of megacystis. Ultrasound and VCUG show an abnormally distended urinary bladder (Fig. 114-33) and, in most cases, hydroureteronephrosis.73 Urinary bladder emptying is abnormal, although no anatomic obstruction is found. Contrast enema examination reveals a severe microcolon and diminished or absent colonic peristalsis (Fig. 114-34).72,73

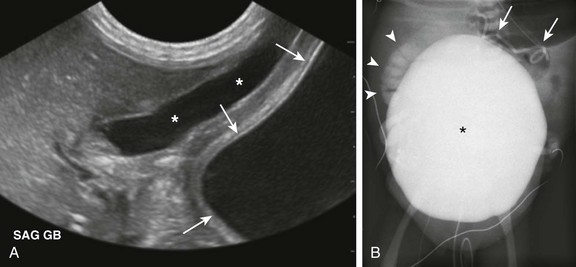

Figure 114-33 A 1-day-old boy with megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis-malrotation syndrome (Berdon syndrome).

A, A longitudinal ultrasound image demonstrates a markedly dilated urinary bladder (arrows), which extends into the upper abdomen and abuts the gallbladder (asterisks). B, A voiding cystourethrogram image shows the urinary bladder (asterisk) occupying most of the abdomen and pelvis. High-grade right vesicoureteral reflux is present (arrowheads), and a retained peritoneoamniotic shunt (arrows) projects over the left upper quadrant of the abdomen.

Treatment: This syndrome is commonly fatal in the first year of life because of malnutrition or sepsis, unless the patient receives parenteral nutrition.72–75 Bowel transplantation has been attempted as a treatment option.76 A cutaneous vesicostomy or suprapubic cystostomy may assist with urinary bladder drainage.73

Bladder Exstrophy

Overview: Deficiency of the anterior abdominal wall with an open, everted, incompletely formed urinary bladder is referred to as bladder exstrophy. The anterior wall of the urinary bladder and overlying skin are absent, and the rectus abdominis muscles are separated inferiorly.1,77 The remaining posterior urinary bladder wall is continuous with the skin.77

Etiology and Clinical Presentation: Failure of migration of mesenchymal cells between ectoderm and cloaca during the fourth week of fetal life leads to incomplete closure of the midline lower anterior abdominal wall in utero, resulting in bladder exstrophy.1,77,78 This rare, unpredictable, congenital defect occurs in 1 : 10,000 to 1 : 40,000 live births and is more common in boys.1 Upon physical examination, the ureteral orifices may be visualized draining into the posterior urinary bladder wall. Epispadias in boys and bifid clitoris in girls often are noted as well.77 Other skeletal, scrotal, renal, spinal, and anorectal anomalies also may be present.1,77

Imaging: Radiographs show abnormal pubic symphyseal widening (Fig. 114-35).77,79 The hips may be dislocated. Renal imaging is most commonly normal at birth.77 Recently, MRI has been used to assess pelvic anatomy after bladder exstrophy repair.80

Figure 114-35 A neonate with bladder exstrophy and a bifid scrotum.

An abdominal radiograph shows symphyseal diastasis, consistent with bladder exstrophy. A round, masslike opacity projecting over the pelvis is due to a large umbilical hernia. Incidental note is made of multiple lumbar vertebral anomalies.

Treatment: The prognosis for bladder exstrophy is generally good. Although certain patients may be amenable to complete primary closure,81 others may require multiple surgeries involving the genitourinary and skeletal systems early in life. An increased incidence of adenocarcinoma of the bladder later in life is found compared with age-matched control subjects.1,82

Cloacal Exstrophy

Overview, Etiology, and Clinical Presentation: Cloacal exstrophy is a nonhereditary constellation of congenital anomalies that involves the anterior abdominal wall and multiple organ systems. This condition is a result of maldevelopment of the cloacal membrane during organogenesis. The infraumbilical cloacal membrane persists, which interferes with normal infraumbilical anterior abdominal wall closure and leads to failure of urogenital septum separation from the rectum. Two hemibladders are separated by ileocecal bowel mucosa.83 The terminal ileum prolapses through the exposed cecum (sometimes called an “elephant trunk” deformity).83 Associated anomalies include omphalocele, abnormal genitalia, a two-vessel umbilical cord, closed spinal defects, and renal abnormalities.

Imaging: Radiographs may demonstrate a variety of abnormalities, including abnormal widening of the pubic symphysis, lumbosacral spine anomalies, developmental dysplasia of the hip, and clubfoot. Imaging of the kidneys may reveal agenesis or ectopia, and various Müllerian anomalies may be detected in the pelvis (Fig. 114-36 and Box 114-2). Ultrasound and MRI imaging of the spine commonly reveal spinal dysraphism and spinal cord tethering (e-Fig. 114-37). At some point, upper gastrointestinal series evaluation should be performed because midgut malrotation may be present in up to 30% of affected children.83

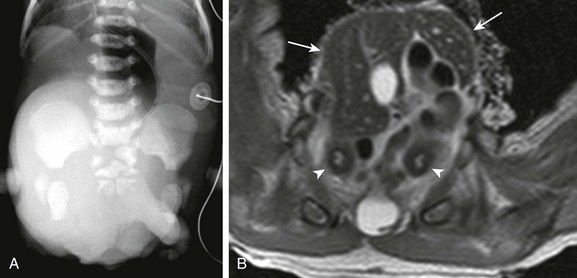

Figure 114-36 A neonate with cloacal exstrophy.

A, An abdominal radiograph shows multiple sacral anomalies and abnormal widening of the pubic symphysis. A masslike opacity projecting over the lower abdomen and pelvis was due to a large omphalocele. B, An axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image shows a large liver-containing omphalocele at the level of the pelvis (arrows). Two separate uterine horns (arrowheads) can be seen, consistent with uterus didelphys. The ileum had prolapsed through the exposed cecum on physical examination (the so-called “elephant trunk” deformity).

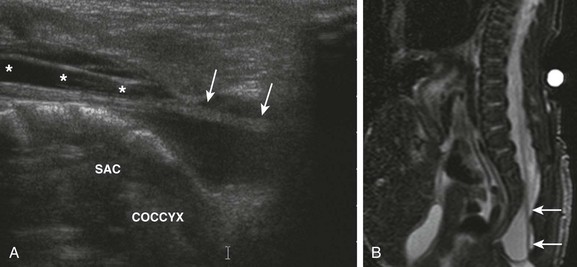

e-Figure 114-37 A neonate with cloacal exstrophy and a tethered spinal cord.

A, A longitudinal ultrasound image of the lumbosacral spinal canal demonstrates a low-lying, elongated conus medullaris (asterisks) with thickening of the filum terminale (arrows). The sacral portion of the thecal sac is abnormally dilated. B, A sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the lumbosacral spine reveals a thickened, tethered filum terminale (arrows).

Cloacal Malformation

Overview, Etiology, and Clinical Presentation: Cloacal malformation is diagnosed when the urinary, genital, and gastrointestinal tracts all come together to form a single outflow channel of variable length.62,85 On physical examination, the perineum has a single opening that eliminates urine, feces, and genital tract secretions.85 Unlike with cloacal exstrophy, the anterior abdominal wall is intact.62 Although the etiology of this congenital anomaly is not entirely understood, it is thought to be the result of failure of urorectal septum to join the cloacal membrane in utero.62 This condition only affects 1 : 40,000 to 1 : 50,000 phenotypic newborn girls.85

Imaging: Contrast injection through a catheter placed within the single perineal orifice under fluoroscopic observation can be used to confirm the diagnosis and definitely characterize perineal anatomy.62,85 Jaramillo et al.85 divided these malformations into urethral and vaginal subtypes based on the appearance of the common channel. Numerous genitourinary tract abnormalities may be seen in the setting of cloacal malformation, including VUR, ureteral ectopia, urinary bladder diverticula, urinary bladder duplication, urachal anomalies, urethral duplication, and a variety of uterine and vaginal anomalies.85 Renal abnormalities may include agenesis, obstruction, and horseshoe kidney, whereas osseous abnormalities may include widening of the pubic symphysis and partial sacral agenesis. Abnormalities of the spinal cord may be present and are best characterized by ultrasound or MRI (Fig. 114-38). Contrast material injection through the distal limb of a diverting colostomy also may be performed to further assess perineal anatomy.62,85

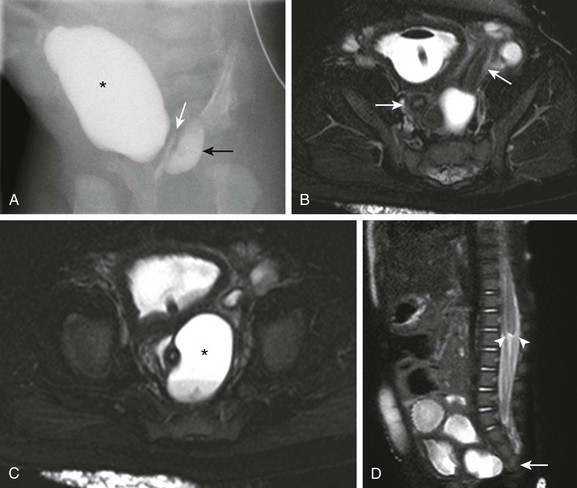

Figure 114-38 Cloacal malformation in a 2-month-old girl.

A, Fluoroscopic contrast material injection through the common channel fills the urinary bladder (asterisk), vagina (white arrow), and rectum (black arrow). B, An axial heavily T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image with fat saturation shows two separate uterine horns (arrows), consistent with uterus didelphys. A balloon catheter is present in the urinary bladder. C, Another axial MR image at a slightly lower level reveals two vaginas. The left hemivagina is obstructed (asterisk) and contains a fluid-fluid level due to hematocolpos. D, A sagittal single shot fast spin echo MR image with fat saturation demonstrates partial sacral agenesis (arrow) and truncation of the lower spinal cord with blunting of the conus medullaris (arrowheads). (From Jarboe MD, Teitelbaum DH, Dillman JR. Combined 3D rotational fluoroscopic MRI cloacagram procedure defines luminal and extraluminal pelvic anatomy prior to surgical reconstruction of cloacal and other complex pelvic malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:757-763.)

Treatment: The goals of surgery are to achieve urinary and fecal continence and to preserve future sexual function. The surgical approach depends, at least in part, on the length of the common channel. A diverting colostomy may be performed soon after birth as a temporizing measure. Hematocolpos/hydrocolpos due to vaginal obstruction should be drained when present. Posterior sagittal anorectovaginourethroplasty often is performed to definitely repair the entire malformation with good results, although laparotomy also may be required.86

Avni, FE, Guissard, G, Hall, M, et al. Hereditary polycystic kidney diseases in children: changing sonographic patterns through childhood. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:169–174.

Avni, FE, Nicaise, N, Hall, M, et al. The role of MR imaging for the assessment of complicated duplex kidneys in children: preliminary report. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:215–223.

Berrocal, T, Lopez-Pereira, P, Arjonilla, A, et al. Anomalies of the distal ureter, bladder, and urethra in children: embryologic, radiologic, and pathologic features. Radiographics. 2002;22:1139–1164.

Jain, M, LeQuesne, GW, Bourne, AJ, et al. High-resolution ultrasonography in the differential diagnosis of cystic diseases of the kidney in infancy and childhood: preliminary experience. J Ultrasound Med. 1997;16:235–240.

Jaramillo, D, Lebowitz, RL, Hendren, WH. The cloacal malformation: radiologic findings and imaging recommendations. Radiology. 1990;177:441–448.

McDaniel, BB, Jones, RA, Scherz, H, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR urography in the evaluation of pediatric hydronephrosis: Part 2, anatomic and functional assessment of uteropelvic junction obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1608–1614.

Rabelo, EA, Oliveira, EA, Diniz, JS, et al. Natural history of multicystic kidney conservatively managed: a prospective study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:1102–1107.

Traubici, J, Daneman, A. High-resolution renal sonography in children with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1630–1633.

References

1. Cohen, HL, Kravets, F, Zucconi, W, et al. Congenital abnormalities of the genitourinary system. Semin Roentgenol. 2004;39:282–303.

2. Felson, B, Cussen, LJ. The hydronephrotic type of unilateral congenital multicystic disease of the kidney. Semin Roentgenol. 1975;10:113–123.

3. Griscom, NT, Vawter, GF, Fellers, FX. Pelvoinfundibular atresia: the usual form of multicystic kidney: 44 unilateral and two bilateral cases. Semin Roentgenol. 1975;10:125–131.

4. Belk, RA, Thomas, DF, Mueller, RF, et al. A family study and the natural history of prenatally detected unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney. J Urol. 2002;167:666–669.

5. Aslam, M, Watson, AR. Unilateral multicystic dysplastic kidney: long term outcomes. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:820–823.

6. Snodgrass, WT. Hypertension associated with multicystic dysplastic kidney in children. J Urol. 2000;164:472–473. [discussion 473-474].

7. Rabelo, EA, Oliveira, EA, Diniz, JS, et al. Natural history of multicystic kidney conservatively managed: a prospective study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:1102–1107.

8. Rickwood, AM, Anderson, PA, Williams, MP. Multicystic renal dysplasia detected by prenatal ultrasonography. Natural history and results of conservative management. Br J Urol. 1992;69:538–540.

9. Vinocur, L, Slovis, TL, Perlmutter, AD, et al. Follow-up studies of multicystic dysplastic kidneys. Radiology. 1988;167:311–315.

10. Rottenberg, GT, De Bruyn, R, Gordon, I. Sonographic standards for a single functioning kidney in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:1255–1259.

11. Flack, CE, Bellinger, MF. The multicystic dysplastic kidney and contralateral vesicoureteral reflux: protection of the solitary kidney. J Urol. 1993;150:1873–1874.

12. Karmazyn, B, Zerin, JM. Lower urinary tract abnormalities in children with multicystic dysplastic kidney. Radiology. 1997;203:223–226.

13. Strife, JL, Souza, AS, Kirks, DR, et al. Multicystic dysplastic kidney in children: US follow-up. Radiology. 1993;186(3):785–788.

14. Avni, EF, Thoua, Y, Lalmand, B, et al. Multicystic dysplastic kidney: natural history from in utero diagnosis and postnatal followup. J Urol. 1987;138:1420–1424.

15. Gordon, AC, Thomas, DF, Arthur, RJ, et al. Multicystic dysplastic kidney: is nephrectomy still appropriate? J Urol. 1988;140:1231–1234.

16. Avni, FE, Garel, L, Cassart, M, et al. Perinatal assessment of hereditary cystic renal diseases: the contribution of sonography. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:405–414.

17. Wood, BP. Renal cystic disease in infants and children. Urol Radiol. 1992;14(4):284–295.

18. Hateboer, N, v Dijk, MA, Bogdanova, N, et al. Comparison of phenotypes of polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. European PKD1-PKD2 Study Group. Lancet. 1999;353:103–107.

19. Hartman, DS. Renal cystic disease in multisystem conditions. Urol Radiol. 1992;14:13–17.

20. MacDermot, KD, Saggar-Malik, AK, Economides, DL, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (PKD1) presenting in utero and prognosis for very early onset disease. J Med Genet. 1998;35:13–16.

21. Hayden, CK, Jr., Swischuk, LE. Renal cystic disease. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1991;12:361–373.

22. Pretorius, DH, Lee, ME, Manco-Johnson, ML, et al. Diagnosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in utero and in the young infant. J Ultrasound Med. 1987;6:249–255.

23. Wood, BP. Renal cystic disease in infants and children. Urol Radiol. 1992;14(4):284–295.

24. Xu, HW, Yu, SQ, Mei, CL, et al. Screening for intracranial aneurysm in 355 patients with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Stroke. 2011;42:204–206.

25. Butler, WE, Barker, FG, 2nd., Crowell, RM. Patients with polycystic kidney disease would benefit from routine magnetic resonance angiographic screening for intracerebral aneurysms: a decision analysis. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:506–515. [discussion 515-516].

26. Traubici, J, Daneman, A. High-resolution renal sonography in children with autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(5):1630–1633.

27. Lonergan, GJ, Rice, RR, Suarez, ES. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20:837–855.

28. Ward, CJ, Hogan, MC, Rossetti, S, et al. The gene mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease encodes a large, receptor-like protein. Nat Genet. 2002;30:259–269.

29. Mercado-Deane, MG, Beeson, JE, John, SD. US of renal insufficiency in neonates. Radiographics. 2002;22:1429–1438.

30. Avni, FE, Guissard, G, Hall, M, et al. Hereditary polycystic kidney diseases in children: changing sonographic patterns through childhood. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:169–174.

31. Kern, S, Zimmerhackl, LB, Hildebrandt, F, et al. Rare-MR-urography—a new diagnostic method in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Acta Radiol. 1999;40:543–544.

32. Roy, S, Dillon, MJ, Trompeter, RS, et al. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease: long-term outcome of neonatal survivors. Pediatr Nephrol. 1997;11:302–306.

33. Stunell, H, McNeill, G, Browne, RF, et al. The imaging appearances of calyceal diverticula complicated by urolithiasis. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:888–894.

34. Kavukcu, S, Cakmakci, H, Babayigit, A. Diagnosis of caliceal diverticulum in two pediatric patients: a comparison of sonography, CT, and urography. J Clin Ultrasound. 2003;31:218–221.

35. Siegel, MJ, McAlister, WH. Calyceal diverticula in children: unusual features and complications. Radiology. 1979;131:79–82.

36. Timmons, JW, Jr., Malek, RS, Hattery, RR, et al. Caliceal diverticulum. J Urol. 1975;114:6–9.

37. Monga, M, Smith, R, Ferral, H, et al. Percutaneous ablation of caliceal diverticulum: long-term followup. J Urol. 2000;163:28–32.

38. Gross, AJ, Herrmann, TR. Management of stones in calyceal diverticulum. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:136–140.

39. Lucaya, J, Enriquez, G, Delgado, R, et al. Infundibulopelvic stenosis in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:471–474.

40. Gittes, RF, Talner, LB. Congenital megacalices versus obstructive hydronephrosis. J Urol. 1972;108:833–836.

41. Pieretti-Vanmarcke, R, Pieretti, A, Pieretti, RV. Megacalycosis: a rare condition. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:1077–1079.

42. Vargas, B, Lebowitz, RL. The coexistence of congenital megacalyces and primary megaureter. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:313–316.

43. Shopfner, CE. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1966;98:148–159.

44. Ross, JH, Kay, R, Knipper, NS, et al. The absence of crossing vessels in association with ureteropelvic junction obstruction detected by prenatal ultrasonography. J Urol. 1998;160:973–975. [discussion 994].

45. Fernbach, SK, Zawin, JK, Lebowitz, RL. Complete duplication of the ureter with ureteropelvic junction obstruction of the lower pole of the kidney: imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:701–704.

46. Joseph, DB, Bauer, SB, Colodny, AH, et al. Lower pole ureteropelvic junction obstruction and incomplete renal duplication. J Urol. 1989;141:896–899.

47. Lebowitz, RL, Blickman, JG. The coexistence of ureteropelvic junction obstruction and reflux. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;140:231–238.

48. McGrath, MA, Estroff, J, Lebowitz, RL. The coexistence of obstruction at the ureteropelvic and ureterovesical junctions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;149:403–406.

49. Frauscher, F. Value of contrast-enhanced color Doppler imaging for detection of crossing vessels in patients with ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Radiology. 2000;217:916–917.

50. Mitsumori, A, Yasui, K, Akaki, S, et al. Evaluation of crossing vessels in patients with ureteropelvic junction obstruction by means of helical CT. Radiographics. 2000;20:1383–1393. [discussion 1393-1395].

51. Conway, JJ, Maizels, M. The “well tempered” diuretic renogram: a standard method to examine the asymptomatic neonate with hydronephrosis or hydroureteronephrosis. A report from combined meetings of The Society for Fetal Urology and members of The Pediatric Nuclear Medicine Council—The Society of Nuclear Medicine. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:2047–2051.

52. Rossleigh, MA. Renal cortical scintigraphy and diuresis renography in infants and children. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:91–95.

53. Little, SB, Jones, RA, Grattan-Smith, JD. Evaluation of UPJ obstruction before and after pyeloplasty using MR urography. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(suppl 1):S106–S124.

54. McDaniel, BB, Jones, RA, Scherz, H, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR urography in the evaluation of pediatric hydronephrosis: Part 2, anatomic and functional assessment of uteropelvic junction obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1608–1614.

55. Perez-Brayfield, MR, Kirsch, AJ, Jones, RA, et al. A prospective study comparing ultrasound, nuclear scintigraphy and dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of hydronephrosis. J Urol. 2003;170:1330–1334.

56. Takla, NV, Hamilton, BD, Cartwright, PC, et al. Apparent unilateral ureteropelvic junction obstruction in the newborn: expectations for resolution. J Urol. 1998;160:2175–2178.

57. Ylinen, E, Ala-Houhala, M, Wikstrom, S. Outcome of patients with antenatally detected pelviureteric junction obstruction. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:880–887.

58. Chertin, B, Pollack, A, Koulikov, D, et al. Conservative treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children with antenatal diagnosis of hydronephrosis: lessons learned after 16 years of follow-up. Eur Urol. 2006;49:734–738.

59. Gonzalez, R, Schimke, CM. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction in infants and children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:1505–1518.

60. Fernbach, SK, Feinstein, KA, Spencer, K, et al. Ureteral duplication and its complications. Radiographics. 1997;17:109–127.

61. Share, JC, Lebowitz, RL. Ectopic ureterocele without ureteral and calyceal dilatation (ureterocele disproportion): findings on urography and sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:567–571.

62. Berrocal, T, Lopez-Pereira, P, Arjonilla, A, et al. Anomalies of the distal ureter, bladder, and urethra in children: embryologic, radiologic, and pathologic features. Radiographics. 2002;22:1139–1164.

63. Lee, PH, Diamond, DA, Duffy, PG, et al. Duplex reflux: a study of 105 children. J Urol. 1991;146:657–659.

64. Avni, FE, Nicaise, N, Hall, M, et al. The role of MR imaging for the assessment of complicated duplex kidneys in children: preliminary report. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:215–223.

65. dorisio, O, Elia, A, Landi, L, et al. Effectiveness of primary endoscopic incision in treatment of ectopic ureterocele associated with duplex system. Urology. 2011;77:191–194.

66. Garcia-Aparicio, L, Krauel, L, Tarrado, X, et al. Heminephroureterectomy for duplex kidney: laparoscopy versus open surgery. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;6(2):157–160.

67. Lin, CC, Tsai, JD, Sheu, JC, et al. Segmental multicystic dysplastic kidney in children: clinical presentation, imaging finding, management, and outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:1856–1862.

68. Das Narla, L, Doherty, RD, Hingsbergen, EA, et al. Pediatric case of the day. Prune-belly syndrome (Eagle-Barrett syndrome, triad syndrome). Radiographics. 1998;18:1318–1322.

69. Herman, TE, Siegel, MJ. Prune belly syndrome. J Perinatol. 2009;29:69–71.

70. Volmar, KE, Fritsch, MK, Perlman, EJ, et al. Patterns of congenital lower urinary tract obstructive uropathy: relation to abnormal prostate and bladder development and the prune belly syndrome. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001;4:467–472.

71. Strand, WR. Initial management of complex pediatric disorders: prune belly syndrome, posterior urethral valves. Urol Clin North Am. 2004;31:399–415. [vii].

72. Levin, TL, Soghier, L, Blitman, NM, et al. Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis and prune belly: overlapping syndromes. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:995–998.

73. Berdon, WE, Baker, DH, Blanc, WA, et al. Megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: a new cause of intestinal obstruction in the newborn. Report of radiologic findings in five newborn girls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;126:957–964.

74. Munch, EM, Cisek, LJ, Jr., Roth, DR. Magnetic resonance imaging for prenatal diagnosis of multisystem disease: megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. Urology. 2009;74:592–594.

75. Magana Pintiado, MI, Al-Kassam Martinez, M, Bousono Garcia, C, et al. The megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome: apropos of a case with prolonged survival. Nutr Hosp. 2008;23:513–515.

76. Masetti, M, Rodriguez, MM, Thompson, JF, et al. Multivisceral transplantation for megacystis microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome. Transplantation. 1999;68:228–232.

77. White, P, Lebowitz, RL. Exstrophy of the bladder. Radiol Clin North Am. 1977;15:93–107.

78. Mildenberger, H, Kluth, D, Dziuba, M. Embryology of bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23:166–170.

79. Muecke, EC, Currarino, G. Congenital widening of the pubic symphysis: associated clinical disorders and roentgen anatomy of affected bony pelves. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1968;103:179–185.

80. Halachmi, S, Farhat, W, Konen, O, et al. Pelvic floor magnetic resonance imaging after neonatal single stage reconstruction in male patients with classic bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 2003;170:1505–1509.

81. Grady, RW, Carr, MC, Mitchell, ME. Complete primary closure of bladder exstrophy. Epispadias and bladder exstrophy repair. Urol Clin North Am. 1999;26:95–109. [viii].

82. Paulhac, P, Maisonnette, F, Bourg, S, et al. Adenocarcinoma in the exstrophic bladder. Urology. 1999;54:744.

83. Meglin, AJ, Balotin, RJ, Jelinek, JS, et al. Cloacal exstrophy: radiologic findings in 13 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:1267–1272.

84. Thomas, JC, DeMarco, RT, Pope, JC, 4th., et al. First stage approximation of the exstrophic bladder in patients with cloacal exstrophy—should this be the initial surgical approach in all patients? J Urol. 2007;178:1632–1635. [discussion 1635-1636].

85. Jaramillo, D, Lebowitz, RL, Hendren, WH. The cloacal malformation: radiologic findings and imaging recommendations. Radiology. 1990;177:441–448.

86. Pena, A, Levitt, MA, Hong, A, et al. Surgical management of cloacal malformations: a review of 339 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:470–479.