Chapter 5 Congenital Abnormalities of the Pericardium

Congenital absence of the pericardium was recognized by M. Realdus Columbus1 in 1559 and by Matthew Baille2 in 1793, but the anomaly was not clinically diagnosed in a chest x-ray until 1959.3 The pericardial abnormality varies from a localized defect to complete absence.4–6 The sternum, abdominal wall, pericardium, and part of the diaphragm arise from somatic mesoderm. Morphogenesis of congenital defects of the left pericardium has been attributed to premature atrophy of the left duct of Cuvier that results in deficient blood supply to the left pleuropericardial membrane.7,8

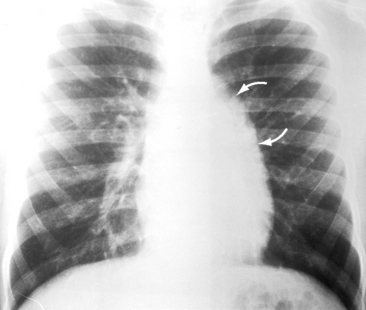

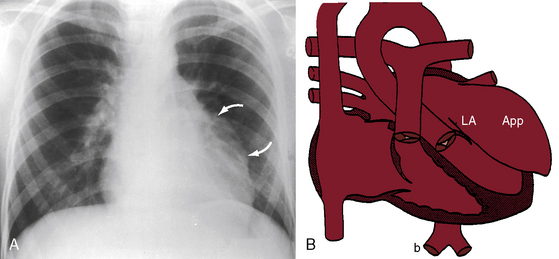

The necropsy incidence rate of congenital absence of the pericardium has been estimated at 1/14,000.9 About two thirds of cases are represented by partial absence of the left pericardium (Figure 5-1).9–11 Congenital absence of the right pericardium is rare (Figure 5-2).6,12 Approximately one third of congenital pericardial defects occur in conjunction with other congenital malformations, both cardiac (Figure 5-3) and noncardiac.4,13,14 A case in point is the Cantrell’s syndrome described in 195813 (also called the Cantrell-Heller-Ravitch syndrome) that consists of two major defects, ectopia cordis and epigastric omphalocele, and three lesser defects, cleft of the distal sternum and defects of the anterior diaphragm and diaphragmatic pericardium.13,15,16

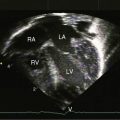

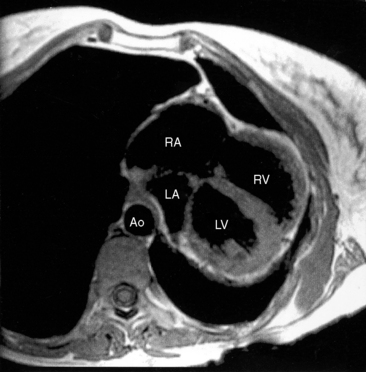

Figure 5-2 Magnetic resonance image with axial view from a 38-year-old woman with congenital complete absence of the pericardium and hypoplasia of the left lower lobe and the left pulmonary artery (see Figure 5-3). The strikingly mobile heart is displaced far into the left thoracic cavity. (LA/RA = left and right atrium; LV/RV = left and right ventricle; Ao = aorta.)

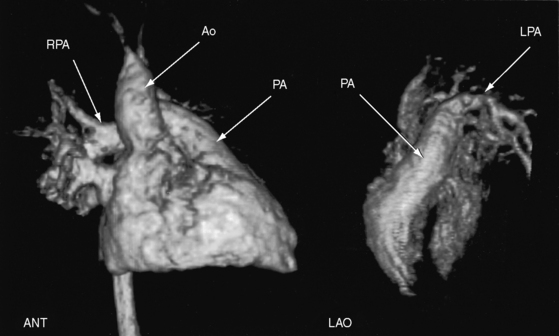

Figure 5-3 Three-dimensional reconstruction of gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography of the heart and great arteries from the 38-year-old woman with congenital complete absence of the pericardium with hypoplasia of the left lower lobe and left pulmonary artery (see Figure 5-2 for magnetic resonance image). The left anterior oblique view (LAO) discloses a hypoplastic left pulmonary artery (LPA). The anterior view (ANT) discloses a well-formed main pulmonary artery (PA) and a well-formed right pulmonary artery (RPA). (Ao = ascending aorta.)

The parietal pericardium exerts contact stress that contributes to ventricular diastolic pressure and limits acute dilation.17 The stress is greater on the relatively thin right ventricle and right atrium whose dimensions and pressures depend chiefly on pericardial constraint.17 Accordingly, congenital complete absence of the parietal pericardium is accompanied by alterations in systemic venous return18 and an increase in right ventricular size.17 Alternans of the right ventricular diastolic pressure has been reported during cardiac catheterization in a patient with congenital complete absence of the pericardium.19

History

Partial or complete absence of the pericardium usually comes to light because of an abnormality on the routine chest x-ray of an asymptomatic patient or in a chest x-ray taken as part of the cardiovascular evaluation of a symptomatic patient with coexisting cardiac defects.4 The most common symptom is chest pain that appears suddenly in a previously asymptomatic adult and that varies from mild and occasional to frequent, prolonged, and debilitating.4 The pain is stabbing; left-sided; brief, if not fleeting; unrelated to exertion but aggravated by position, especially the left lateral decubitus; awakens the patient from sleep; and is relieved with an upright position.6,20 The pain associated with partial absence of the left pericardium (see Figure 5-1) is attributed to herniation of the left atrial appendage through the pericardial defect. The pain associated with complete absence of the pericardium (see Figure 5-2) is believed to originate from torsion of the thoracic inlet.20 In light of evidence of transient compression of coronary arteries, myocardial ischemia is also a consideration.21,22

Familial congenital partial absence of the left pericardium has been reported.7 The male:female prevalence ratio is reportedly 3:1. Longevity is not affected by congenital partial absence of the pericardium20 but has not been established with congenital complete absence. However, one patient reportedly survived to the eighth decade.23

Physical appearance

Congenital partial absence of the left pericardium has been reported with abnormal facies and growth hormone deficiency24 and with VATER defects (V, vertebral defects; A, anal atresia; T, tracheo; E, esophageal fistula; R, radial atresia and renal dysplasia).25

Arterial pulse and jugular venous pulse

The arterial pulse is normal with congenital complete absence of the pericardium despite alternans of diastolic pressure.19 The jugular venous pulse is normal with congenital partial absence of the pericardium and is normal with congenital complete absence, despite the decrease in contact stress exerted on the right atrium and right ventricle.

Precordial movement and palpation

With congenital partial absence of the left pericardium, the position and movements of the heart are normal. With complete absence, a striking mobility of the heart shifts dramatically to the left (see Figure 5-2), a position that can be detected with percussion. Displacement is accompanied by major rotation (see Figure 5-2),6 so identification of a left or right ventricular impulse is not feasible.

Electrocardiogram

With congenital partial absence of the left pericardium, the electrocardiogram results are normal because the heart is not displaced and is inherently normal apart from the pericardial defect. With congenital complete absence of the pericardium, standard precordial lead placements show delayed transition that reflects the leftward position of the heart.4 Axis deviation, generally right, probably results from rotation.4 Incomplete right bundle branch block is frequently mentioned.4 Individual reports are found of complete heart block26 and sinus node dysfunction.27

X-ray

The posteroanterior chest x-ray is a major key to the diagnosis and was the basis for the earliest clinical recognition of congenital absence of the pericardium.3 Congenital partial absence of the left pericardium is accompanied by herniation of the left atrial appendage, represented in the x-ray by a convexity immediately below the pulmonary trunk or, if herniation is larger, by extension of the convexity to the second and third left interspaces (see Figure 5-1). The heart is not displaced, and the cardiac silhouette is otherwise normal. The x-ray of an intrapericardial congenital aneurysm of the left atrial appendage (Figure 5-4)28 is similar if not indistinguishable from the x-ray of partial absence of the left pericardium (see Figure 5-1). A congenital pericardial cyst typically presents as a smooth homogeneous radiodensity in the right cardiophrenic angle, touching the anterior chest wall and the anterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm (Figure 5-5).29 The distinction between congenital partial absence of the pericardium is less clear when the cyst presents along the left cardiac border above the left hemidiaphragm.29

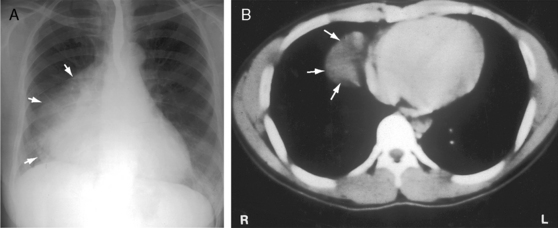

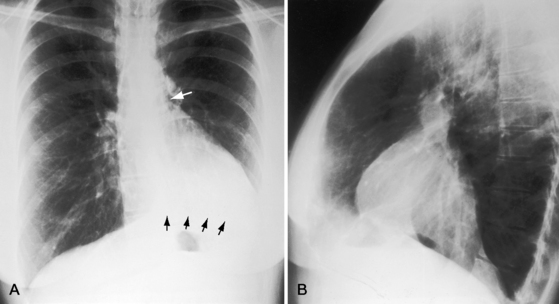

Congenital complete absence of the pericardium is characterized by dramatic mobility of the heart that results in striking leftward and posterior displacement (see Figure 5-5)4 that is even more striking if hypoplasia of the left pulmonary artery and left lung coexist (Figures 5-2 and 5-6). A cardiac shadow to the right of the vertebral column is absent. A tongue of lung tissue is typically interposed between the pulmonary trunk and aorta (see Figure 5-6).4 The definitive clinical diagnosis is based on computed tomographic scan and magnetic resonance imaging (see Figure 5-2).8,30,31

Figure 5-6 X-rays from the 38-year-old woman with congenital complete absence of the pericardium referred to in Figures 5-2 and 5-3. A, The frontal projection shows the marked leftward position of the mobile heart with no cardiac shadow to the right of the vertebral column. The leftward shift was exaggerated by hypoplasia of the left lung indicated by the elevated left hemidiaphragm (black arrows). The white arrow identifies a tongue of lung tissue interposed between the pulmonary trunk and aorta. B, The lateral projection shows the striking posterior position of the mobile heart.

Echocardiogram

The echocardiogram may strongly suggest the diagnosis of congenital absence of the pericardium and can be used to identify coexisting cardiac defects, but magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomographic scan are definitive.32 Distinctive features of the echocardiogram in congenital complete absence of the pericardium are the unorthodox windows required for imaging, leftward and posterior displacement and rotation of the heart, hypermobility with an abnormal swinging movement, paradoxical motion of the ventricular septum, and enlargement of the right ventricle and right atrium.4,33 Lack of normal pericardial constraint has a greater effect on the relatively thin-walled right ventricle, which accounts for right ventricular dilation, for a selective increase in systemic venous return, and for paradoxical motion of the ventricular septum.4,18,33 Congenital partial absence of the pericardium is not an echocardiographic diagnosis. A fetal echocardiogram was used to detect an intrapericardial aneurysm.34

1 Columbus M.R. De re anatomica, N. Beurlaque. 1559:265-269. Venice

2 Baille M. On the want of a pericardium in the human body. Transactions of the Society for Improved Medical and Chirurgical Knowledge. 1793;1:91.

3 Ellis K., Leeds N.E., Himmelstein A. Congenital deficiencies in partial pericardium: review with two new cases including successful diagnosis by plain roentgenography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1959;82:125-137.

4 Gatzoulis M.A., Munk M.D., Merchant N., Van Arsdell G.S., Mccrindle B.W., Webb G.D. Isolated congenital absence of the pericardium: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:1209-1215.

5 Nasser W.K., Helmen C., Tavel M.E., Feigenbaum H., Fisch C. Congenital absence of the left pericardium. Clinical, electrocardiographic, radiographic, hemodynamic, and angiographic findings in six cases. Circulation. 1970;41:469-478.

6 Ratib O., Perloff J.K., Williams W.G. Congenital complete absence of the pericardium. Circulation. 2001;103:3154-3155.

7 Taysi K., Hartmann A.F., Shackelford G.D., Sundaram V. Congenital absence of left pericardium in a family. Am J Med Genet. 1985;21:77-85.

8 Faridah Y., Julsrud P.R. Congenital absence of pericardium revisited. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2002;18:67-73.

9 Southworth H., Stevenson C.S. Congenital defects of the pericardium. Arch Intern Med. 1938;61:223.

10 Mehta S.M., Myers J.L. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: diseases of the pericardium. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69:S191-S196.

11 Van Son J.A., Danielson G.K., Schaff H.V., Mullany C.J., Julsrud P.R., Breen J.F. Congenital partial and complete absence of the pericardium. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:743-747.

12 Karakurt C., Oguz D., Karademir S., Sungur M., Ocal B. Congenital partial pericardial defect and herniated right atrial appendage: a rare anomaly. Echocardiography. 2006;23:784-786.

13 Cantrell J.R., Haller J.A., Ravitch M.M. A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1958;107:602-614.

14 Rais-Bahrami K., Granholm T., Short B.L., Eichelberger M.R. Absence of pericardium in an infant with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Perinatol. 1995;12:172-173.

15 Vazquez-Jimenez J.F., Muehler E.G., Daebritz S., et al. Cantrell’s syndrome: a challenge to the surgeon. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1178-1185.

16 Meeker T.M. Pentalogy of Cantrell: reviewing the syndrome with a case report and nursing implications. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2009;23:186-194.

17 Tyberg J.V., Smith E.R. Ventricular diastole and the role of the pericardium. Herz. 1990;15:354-361.

18 Fukuda N., Oki T., Iuchi A., et al. Pulmonary and systemic venous flow patterns assessed by transesophageal Doppler echocardiography in congenital absence of the pericardium. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:1286-1288.

19 Shah R.P. Diastolic pressure alternans: a new sign in congenital absence of the pericardium. Singapore Med J. 2001;42:78-79.

20 Beppu S., Naito H., Matsuhisa M., Miyatake K., Nimura Y. The effects of lying position on ventricular volume in congenital absence of the pericardium. Am Heart J. 1990;120:1159-1166.

21 Bennett K.R. Congenital foramen of the left pericardium. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:993-998.

22 Rees A.P., Risher W., Mcfadden P.M., Ramee S.R., White C.J. Partial congenital defect of the left pericardium: angiographic diagnosis and treatment by thoracoscopic pericardiectomy: case report. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1993;28:231-234.

23 Hammoudeh A.J., Kelly M.E., Mekhjian H. Congenital total absence of the pericardium: case report of a 72-year-old man and review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;109:805-807.

24 Boscherini B., Galasso C., Bitti M.L. Abnormal face, congenital absence of the left pericardium, mental retardation, and growth hormone deficiency. Am J Med Genet. 1994;49:111-113.

25 Lu C., Ridker P.M. Echocardiographic diagnosis of congenital absence of the pericardium in a patient with VATER association defects. Clin Cardiol. 1994;17:503-504.

26 Varriale P., Rossi P., Grace W.J. Congenital absence of the left pericardium and complete heart block. Report of a case. Dis Chest. 1967;52:405-410.

27 Hano O., Baba T., Hayano M., Yano K. Congenital defect of the left pericardium with sick sinus syndrome. Am Heart J. 1996;132:1293-1295.

28 Tanabe T., Ishizaka M., Ohta S., Sugie S. Intrapericardial aneurysm of the left atrial appendage. Thorax. 1980;35:151-153.

29 Feigin D.S., Fenoglio J.J., Mcallister H.A., Madewell J.E. Pericardial cysts. A radiologic-pathologic correlation and review. Radiology. 1977;125:15-20.

30 Bogaert J., Francone M. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in pericardial diseases. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:14.

31 Kim J.S., Kim H.H., Yoon Y. Imaging of pericardial diseases. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:626-631.

32 Centola M., Longo M., De Marco F., Cremonesi G., Marconi M., Danzi G.B. Does echocardiography play a role in the clinical diagnosis of congenital absence of pericardium? A case presentation and a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Med. 2009;10:687-692.

33 Connolly H.M., Click R.L., Schattenberg T.T., Seward J.B., Tajik A.J. Congenital absence of the pericardium: echocardiography as a diagnostic tool. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1995;8:87-92.

34 Fountain-Dommer R.R., Wiles H.B., Shuler C.O., Bradley S.M., Shirali G.S. Recognition of left atrial aneurysm by fetal echocardiography. Circulation. 2000;102:2282-2283.