CHAPTER 13 Congenital Abnormalities of the Elbow

CAUSES OF CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

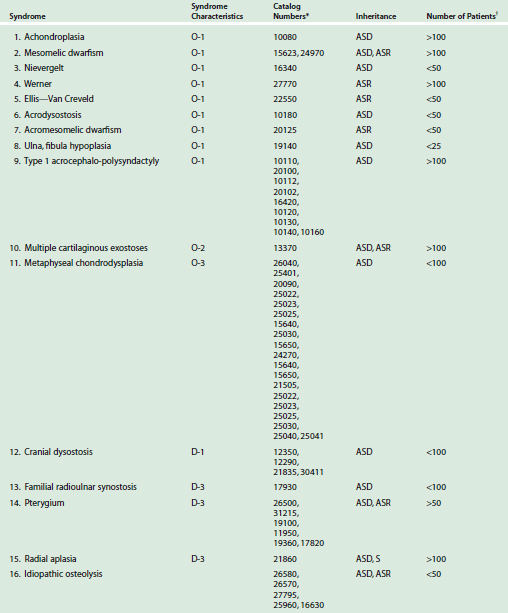

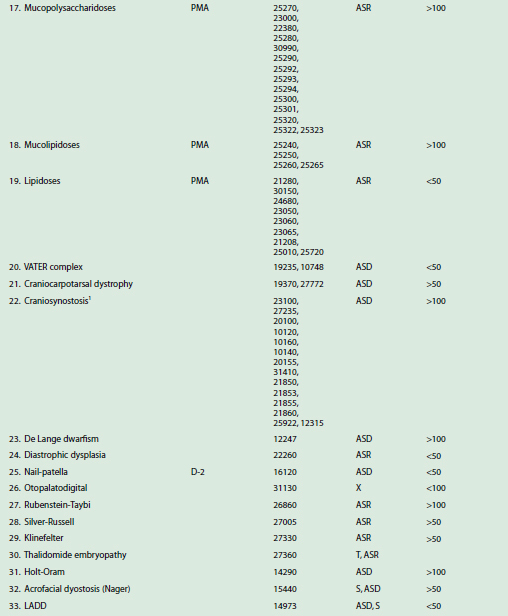

Conditions that commonly involve the elbow are constitutional diseases of bone, metabolic abnormalities, and syndromes featuring limb formation and differentiation failures36,38,43,54,82,90 (Table 13-1). Some of the syndromes can be grouped under broad categories such as osteochondrodysplasia,3,29,33,90 dysostoses,18 primary growth disturbances, primary metabolic abnormalities, and congenital myopathies. Most, however, are chromosomal syndromes, from the common dislocation of the radial head69 through fairly well-known syndromes such as trisomy 18, fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and the Antley-Bixler syndrome7 to such rarities as the Bruck syndrome (osteogenesis imperfecta with congenital joint contractures) and a congenital mirror movement syndrome. In some cases, the specific gene locus has now been identified; for example, elbow synostosis may also occur in the context of the multiple synostosis syndrome,53 which has been reported in large family groups and is the result of mutations in genes controlling TGF-b synthesis, including noggin, a protein believed to be important in establishing morphogenic gradients.

CLASSIFICATION

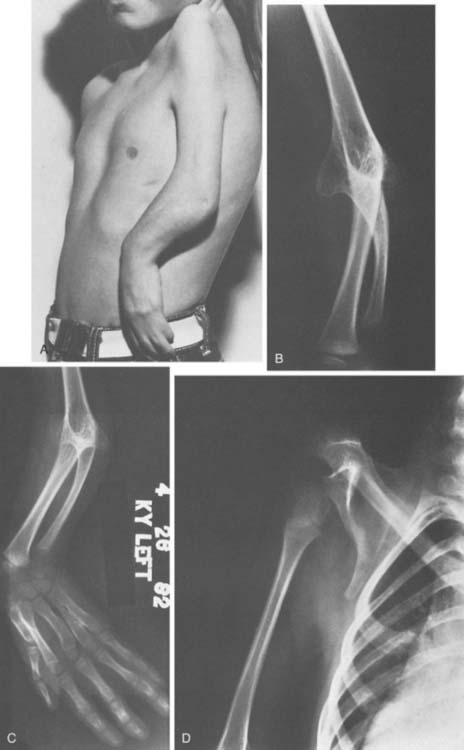

A multitissue defect classification can be based on the most obvious and most inhibiting tissue defect known to be present. Some degree of defect in other tissues is also commonly noted. The classification consists of three major categories: (1) bone and joint anomalies, (2) soft tissue anomalies, and (3) anomalies involving all tissues. Bone and joint abnormalities at the elbow may include major absences, but more commonly the skeletal structures are present but malformed. The common bone and joint problems are synostosis (Fig. 13-1), ankylosis (Figs. 13-2 to 13-4), and instability (Fig. 13-5). Soft tissue anomalies include malformations with contractures, control deficiencies, isolated tissue anomalies (Fig. 13-6), and congenital tumors (Fig. 13-7). Complete absence or disorganization of the whole limb, including elbow structures, may occur, as in phocomelia (Fig. 13-8); usually, recognizable though dysplastic structures are present (Fig. 13-9). Similar involvement, although more isolated to the elbow area, occurs in the pterygium syndromes.

With reference to the bone and joint deformities only, it has been useful to many authors to classify them as congenital, developmental, or post-traumatic. As noted earlier, there is much confusion and interplay between these diagnoses, particularly with reference to radial head subluxation or dislocation. In this classification, congenital refers to a primary genetic dysplasia of the skeletoarticular structure of the elbow, resulting in an observed deformity. Other congenital anomalies or a familial history of similar anomalies help confirm this as an etiology. Developmental refers to elbow skeletal structures that are relatively normal at birth but that are then secondarily deformed by abnormal stresses (perhaps from a congenital shortening of the ulna); by paralysis or other limited motion (arthrogryposis); neural, metabolic, endocrine or dyscrasia disturbances (hemophilia, loss of pain recognition, hemochromatosis, and so on); tumor or hamartomatous involvement (fibromatosis, osteochondromata, and so on), and disease (sickle cell anemia, Gorham’s disease, infections). The post-traumatic etiologic grouping is included in this chapter only because of the continuing confusion over early radial head dislocations, which are often post-traumatic, either as a variant of Monteggia fracture dislocation or as a pure dislocation of the soft cartilaginous radial head pulling through the annular ligament (see Chapter 20) and its residua.

Both early and late, dislocation of the radial head is often diagnosed as a congenital subluxation or dislocation, but it often is not. A radial head subluxation or dislocation in an elbow with normal, neural, muscular, and skeletal structures in both elbow and forearm is post-traumatic until proven otherwise; such an elbow with abnormal skeletal forearm structures is probably due to developmental stresses, but additional trauma may play a part. Such an elbow with a synostosis from birth or other skeletal deformity and no evidence of peri-birth trauma is due to congenital causes, but again, trauma may be an additional factor. The confusions highlighted by this classification have been much discussed in the literature.14,20,38,45,51,54,61,70,71,72,79

DIAGNOSIS

BONE AND JOINT ANOMALIES

Synostosis

Synostoses may occur between all or any two of the three bones present at the elbow. The most common synostosis is that between the radius and the ulna proximally in the forearm, near the elbow (Fig. 13-10), but these two bones also may be joined at any point in their paired course in the forearm. Mital55 has classified these synostoses as type I, proximal to the proximal radial physis, and type II, distal to the proximal radial physis. Type II synostoses are more likely to be associated with congenital dislocation of the radial head.45 Cleary and Omer12 suggested a four-level classification scheme, in which Type I is clinically but not radiographically fused with a reduced normal-appearing radial head; Type II is similar but with a clear, bony synostosis; Type III has a hypoplastic posteriorly dislocated radial head; and Type IV has a hypoplastic anteriorly dislocated radial head. Type III appears to be the most common deformity and the one most likely to be associated with significant rotational deformity (almost always pronation). In addition, radiohumeral synostosis, ulnohumeral synostosis, or synostosis among the radius, humerus, and ulna may be present; often, the synostosis is in association with other limb abnormalities, the most common of which is probably ulnar deficiency.30,31,42,57,84 Synostosis may also be associated with fetal alcohol syndrome.84 Incomplete synostosis may occur, but often, this is a radiologic appearance rather than an actual occurrence, because complete radiographic synostosis is usually present by maturity.27,38,50,82 Cleary and Omer’s five cases of type I synostosis are, however, genuine; all of the patients were skeletally mature at the time of final clinical and radiologic review.12

Synostosis between the humerus and either the radius, ulna, or both is less common. Of these, the humeroradial type is most common, followed by humeroradioulnar and humeroulnar types.52 However, anatomy is not the whole story, and McIntyre and Benson52 have proposed an etiologic classification of developmental elbow synostoses, specifically as to whether the synostosis occurs with (class I, or bony type) or without (class II, or joint type) limb hypoplasia. Within each class, the synostosis can be further characterized as occurring in a sporadic or familial pattern and, if familial, with dominant or recessive inheritance. In familial cases, the condition is usually bilateral.12 One of the more dramatic presentations is in the Antley-Bixler syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by radiohumeral synostosis, cranial synostosis, midface hypoplasia, and a variety of urogenital and cardiac abnormalities (Fig. 13-10C).7 Distal radioulnar dislocation is a common accompaniment of many of these syndromes.

Ankylosis

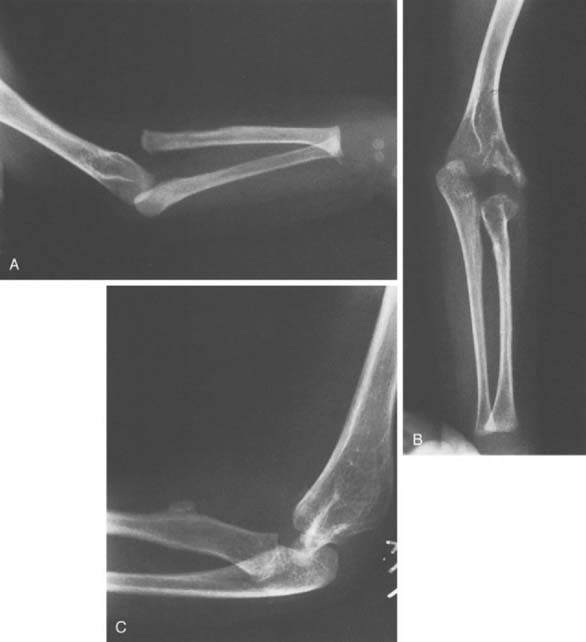

Partial ankylosis of the elbow or the proximal radioulnar joint is often overlooked because limited elbow-forearm motion is common in infancy28 and often not remarked in childhood. Causes include failure of complete synostosis, intrinsic abnormalities of the joint or surface formation mechanism, and abnormalities of the surrounding soft tissues, as occurs in pterygium cubitale. The joint must be formed correctly, must have adequate surface material and ligamentous support, and must move soon after its formation, or it will become ankylosed, as occurs, for example, in arthrogryposis, or, far more rarely, in Apert’s syndrome.35,89 There are instances when all or part of the elbow appears to be dislocated but proves to be only malformed and limited in motion (Fig. 13-11). Patients with dysplasia, such as those with Apert’s syndrome, may show a progressive loss of motion over time.89

FIGURE 13-11 A, Anteroposterior (AP) x-ray view of an apparent radiohumeral dislocation similar to that shown in Figure 13-2 is seen preoperatively. B, A postoperative AP x-ray view 4 years later shows repositioning of what was determined to be a congenital displaced radiohumeral joint without a dislocation of the radial head. C, A lateral postoperative view of the same elbow. Repositioning was obtained when the radius was shortened by removing a segment of the radial shaft. This segment of excised radius was then used to block the repositioned lateral condyle in its new position. This surgical procedure improved the x-ray position of the elbow but did not change function, which demonstrated both preoperatively and postoperatively mild loss of extension-flexion and moderate loss of supination-pronation.

Instability

The most common problem of instability at the elbow is that of radial head subluxation or dislocation.1,2,11,20,22,25,38,47,48,61,64,67,78,79 When subluxation is an isolated phenomenon, there is considerable doubt about whether it is congenital, developmental, or post-traumatic.14,20,38,45,51 The pulled elbow of infancy is a well-known clinical problem that is associated with trivial trauma and laxity or minor tears of the annular ligament.61,70,72,75 Children have been seen at birth or shortly thereafter with similar problems.14,61,75 Furthermore, such subluxations in the infant, if not treated by closed reduction or other means, may result in deformities similar to those described as indicative of congenital dislocation of the radial head. It has been said that the degree of deformity in the few cases of known infantile dislocation that have been left untreated but followed suggest that the resulting deformity is milder than that seen in definite congenital hypoplasia at the elbow. This may be so but the so-called criteria for classifying a radial head dislocation as congenital (see later) may be seen after any early radial head dislocation regardless of cause (Fig. 13-12). By contrast, when traumatic dislocation is unreduced in the older child, the development of the radial head and the capitellum remains fairly normal, displaying only minimally those radiographic features said to be characteristic of congenital radial head dislocation. These features are (1) a dislocated or subluxed radial head, (2) an underdeveloped radial head, (3) a flat or dome-shaped radial head, (4) a more slender radius than normal, (5) a longer radius than normal, (6) an underdeveloped capitellum humeri, and (7) a lack of anterior angulation of the distal humerus.4,20,56,63,88 Bilaterality, especially symmetric bilateral dislocation, is usually also considered evidence of a congenital etiology, but this is not an absolute requirement.48 However, many if not all the features of congenital dislocation can also be seen with developmental dislocation, due to mild degrees of ulnar or capitellar hypoplasia. In such cases the radial head may slowly dislocate with growth, as the paired forearm bones continue to grow at dissimilar rates.4

There may be only one absolute criterion of congenital elbow dislocation—dislocation with severe hypoplasia of all the osseous elements of the elbow. Absence of the capitellum is probably an example of congenital aplasia, but hypoplasia of the capitellum may occur after dislocation from any cause, as may a deformity of the radial head (see Chapter 20).

When radial head dislocation is familial, bilateral, or seen at birth, or when it occurs with other musculoskeletal anomalies, particularly anomalies in the same upper limb, the evidence is strong that the radial head dislocation is congenital. Cases that are diagnosed later in life may be associated with a discrepancy in length of the paired forearm bones and, therefore, may fall within the “developmental” category. It is well known that inadequate length of the ulna from any cause will result in increased compressive stresses along the radius, gradually leading to a subluxation and perhaps a dislocation of the radial head.38,47,79 Such subluxations, therefore, also may be a secondary phenomenon.48

Approximately half of all patients with isolated congenital radial head dislocation will have a problem bilaterally.2,48,56 Bell and associates4 have classified isolated congenital dislocations of the radial head as type I, subluxation; type II, posterior dislocation with minimal displacement; and type III, posterior dislocation with significant proximal migration of the radius. Type I is the least common dislocation but the one most likely to be associated with pain. Types II and III appear to be roughly equally prevalent. Type III is associated with the most loss of motion, usually supination. Deformity of the radial head without subluxation also has been reported.22 Finally, Wiley and colleagues86 have reported congenital anterior and lateral dislocations.

Other Bony Problems

Hypoplasia of the distal humerus may occur; the resulting deformity may cause ulnar neuropathy, either im-mediately, from synovial cysts, or chronically, due to abnormal elbow growth and nerve traction.74 Congenital pseudarthrosis of the olecranon has been reported but is exceedingly rare.66

SOFT TISSUE ANOMALIES

Contractures

The classic malformation with contracture is pterygium cubitale, in which almost every soft tissue is abnormal and a severe flexion contracture exists.23,24 The condition also has been called cutaneous webs and webbed elbow; it is but one manifestation of a congenital syndrome that may affect the neck, axilla, elbow, knee, or digits. A survey of 240 cases of cutaneous webs reported in the literature included 29 in the region of the elbow.23 The web may be unilateral or bilateral, or symmetric or asymmetric. The condition has been reported to result from both an autosomal dominant and a recessive gene. Associated abnormalities involving almost every body system have been reported.38,82 Other conditions resulting in formidable contractures about the elbow include fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and arthrogryposis.

Control Deficiencies

Arthrogryposis and its related syndromes are also included in this group but also are discussed elsewhere (see Chapters 71 and 72). Both flaccid and spastic palsies affect elbow control and range of motion. Simple absences or deficiencies of tissue also affect elbow control. Hypoplasia of the elbow includes deficient growth not only of osseous structures but also of the related soft tissue control elements and cover structures.13,58,81 Most characteristic is probably the extension contracture of arthrogryposis.87

Isolated Tissue Anomalies

The skin may be deficient or missing, with absence, hypoplasia, or scarring of the underlying tissues. Nerve, vascular, and lymphatic anomalies in the region of the elbow are common.38 The anconeus epitrochlearis occasionally is present as an anomalous muscle and may cover the ulnar nerve in the cubital tunnel area, contributing to the possibility of entrapment. Other anomalous muscles that may cause nerve entrapment problems are (1) Gantzer’s muscle, an anomalous head of the flexor pollicis longus or flexor profundus that usually originates from the medial epicondyle or the coronoid process of the ulna and occasionally is a factor in anterior interosseous nerve compression; (2) a solitary head of the supinator and other anomalies of this muscle; (3) accessory muscles of the anterolateral aspect of the elbow, including the accessory brachialis or accessory brachioradialis; (4) variations in the head, origin, or insertion of the pronator teres; (5) variations of a similar nature in the flexor carpi radialis, the flexor carpi ulnaris, and the palmaris longus53; and (6) an aberrant medial head of the triceps, which may snap over the medial epicondyle and irritate the ulnar nerve.16

COMBINED BONE AND SOFT TISSUE ANOMALIES

Soft tissue anomalies may coexist with mild osseous anomalies, such as those related to the supracondyloid process.13,53,80 The supracondyloid process is an anomalous bony prominence extending from the anteromedial aspect of the distal third of the humerus. Struthers81 in 1848 described the ligament associated with this process, and since then, various anomalies have been reported in connection with it. These include a more proximal branching of the ulnar artery off the brachial artery above the bony spur, a more proximal insertion of the pronator teres on the bony process, and various relationships of the neurovascular structures with bone and ligament. The symptoms—pain, tingling, numbness, and so on—usually are neuralgic, but they may be vascular.

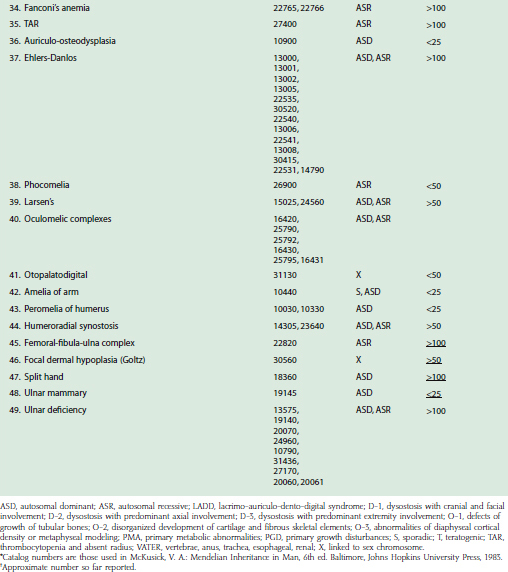

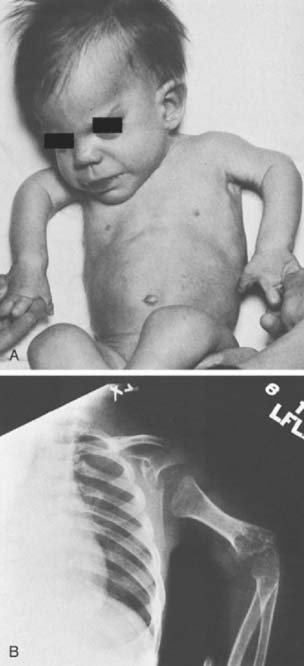

Severe ulnar hypoplasia is marked by radial head dislocation, diminishing segments (ranging from small to nonexistent) of the proximal ulna, variable but seldom normal motion and stability, and muscle and neurovascular abnormalities. Conditions are more normal proximal to the elbow, but distally, more abnormalities are apparent; the ulnar forearm and hand structures are particularly dysplastic. Lorea et al46 have proposed a classification of these findings based on a review of their own experience with 46 patients and a literature review. They propose three elbow types: type 1, normal; type 2, radiohumeral synostosis; and type 3, radial head subluxation. They further recommend subclassifying the elbows as having extension (type E) or flexion (type F) contractures. Unfortunately, they do not give the distribution of these types in their series. Phocomelia may present with similar findings, or the elbow may be even more dysplastic or absent altogether (hand, wrist, or forearm may be attached directly to the shoulder or trunk).

TREATMENT OF BONE AND JOINT DYSPLASIAS

TREATMENT OF SYNOSTOSIS

The treatment of synostosis of the elbow joint, whether radiohumeral60 or ulnohumeral, is dictated by the position of the forearm-wrist-hand unit and the function of the wrist-hand unit. These treatments have changed little over the past few decades. If the hand is absent or nonfunctional, repositioning of a synostotic elbow is clearly less important. If the hand is functional and the elbow is in a “functional” position (i.e., somewhere near midflexion), especially if the contralateral limb is normal, no treatment is likely to be necessary. For bilateral synostoses, some consideration probably should be given to positioning one arm in relative flexion and the other in relative extension.

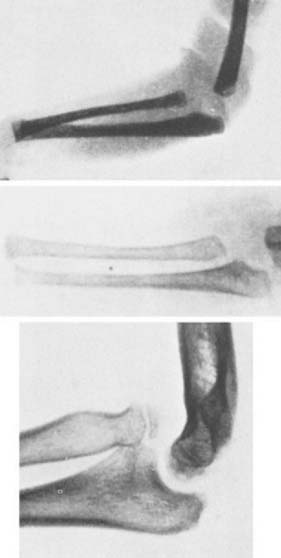

Frequently, only one forearm bone is well represented, and this may be bowed or deformed in some manner as well as short. In addition, there may be a rotational deformity. The forearm-wrist-hand unit may point directly posterior when the upper limb is in its usual dependent position beside the torso. Although simple rotational deformities can be corrected by osteotomy at any level, multiplane deformities should be corrected at the site of maximum deformity—that is, the humeral-forearm junction—perhaps extending the correction distally in the forearm (Fig. 13-13). One such method involves a posterior approach and a multiple-segment corrective osteotomy, making one or more of the segments trapezoidal in shape and rotating it 180 degrees, if necessary, to realign the unit as desired. If only one limb is involved, this desired position is usually at maximum length, with the forearm, wrist, and hand in the midposition. Derotation should be accomplished in the direction that causes the least torsion of the neurovascular structures, commonly from an internally rotated position through a clockwise rotation to a forearm midposition. Hyperextension, if present, is corrected simply to neutral or slight flexion, and the osteotomy segments are adjusted to make the best contact in the desired position; a segment may be excised if this is needed for contouring. If both limbs are involved, enough elbow flexion angle should be included on one side to allow one of the limbs to reach the face and the head. Arthroplasty has been attempted30,31,39,57 but with indifferent results; the usual result is recurrence.

Proximal forearm synostosis may occur with elbow synostosis, in which case the elbow is derotated as described previously. If, however, proximal radioulnar synostosis occurs in the presence of a functioning elbow joint, derotation of the forearm alone may be required. The indications for this procedure seem limited. Most patients have little functional deficit.12 Compensatory rotation at the wrist appears to be an important factor in minimizing symptoms.62 Although many authors have attempted and a few have claimed success for passive and even active mobilization of the forearm,8,15,19,27,37,55 there is no body of literature that substantiates these results in a significant number of patients who have been followed for an adequate period of time. When attempted, these procedures usually involve excision of the proximal radius, including the synostotic mass; division of the entire length of the interosseous membrane; interposition of some material between the contact areas of the radius and the ulna; and tendon transfers, such as rerouting the extensor carpi radialis longus to the volar wrist for supination and the flexor carpi radialis to the dorsal wrist for pronation. A similar procedure involving the interposition of a metallic swivel has been described by Kelikian and Doumanian,37 but few long-term results have been reported.

A more reliable procedure is that of derotation osteotomy.27,76 This procedure is best outlined by Green and Mital,24,55 who perform the rotational osteotomy through the synostosis itself. It is indicated primarily when the forearm is fused in the extreme of either pronation or supination; forearms synostotic in neutral or close to neutral function well and often are diagnosed only later in infancy or childhood because of this fact. The synostosis is approached through a dorsal incision and is transversely osteotomized. A radioulnar (in the coronal plane) K-wire or Steinmann pin is then placed distal to the osteotomy site and is left protruding externally on both sides. A longitudinal (in the sagittal plane) pin is then placed from the olecranon across the osteotomy site, and corrective rotation is carried out as desired. Because the indication is an extreme pronated or supinated position, in most instances, 70 to 90 degrees of rotation from pronation toward supination is required. If circulatory deficits appear during or after this derotation, less rotation is accepted, although an additional amount may be carried out 10 to 15 days later. The radioulnar pin may be fixed by either a plaster cast or an external fixation apparatus. Internal fixation should not be used because alteration of forearm rotation may be necessary to diminish circulatory difficulties. Goldner and associates21 claim that these circulatory problems may be minimized by the use of derotation in the distal forearm (radius only in younger patients; radius and ulna in older patients). Their results have yet to appear in the literature except in abstract form, but the rationale seems reasonable and the technique appropriate. They recommend cross-pin fixation in children and plate fixation in adolescents and adults.

One new and unusual problem has been reported recently, as an acute sequela of proximal radioulnar synostosis: flexion contracture. Matsuko et al49 have reported five cases in which an acute hyperflexion episode had resulted in the sudden onset of a fixed flexion contracture in teenaged boys (in four of the five cases). In each case, the problem was treated surgically. Through a lateral approach, the anterior elbow capsule was identified. In each case, a thickened band of anterior capsule was identified, under which the hyperflexed, anteriorly displaced radial head had become trapped. A simple excision of the band resulted in complete correction in each case.

TREATMENT OF ANKYLOSIS

Ankylosis that does not involve synostosis, subluxation, or dislocation of the elbow may occur. Paralyses, muscle disease, and other soft tissue abnormalities commonly restrict motion; treatment of these abnormalities is discussed elsewhere (see Chapters 71 and 72). Abnormalities of joint shape and joint cartilage occur but are usually treated only by physical therapy. Rotation ankylosis due to soft tissue abnormalities occurs but has minimal effect on the elbow; its treatment requires release not only of the proximal radioulnar area but also in the forearm and wrist.5

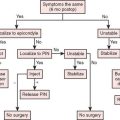

TREATMENT OF INSTABILITY

Treatment of infantile dislocations of the radial head, whether congenital, developmental, or traumatic, depends on the degree of hypoplasia present in the forearm and elbow area. If in doubt about the configuration of the various components of the elbow joint, an arthrogram should be performed61; this study may show that there is no dislocation at all but merely a deformed elbow joint with the radiocapitellar joint displaced from the usual position (see Fig. 13-12). Attempts at open reduction have been made, but the result is often recurrence unless both annular ligaments and ulnar length/configuration are restored (Fig. 13-14). Most authors do not advise the procedure,4,56,86 although recently Sachar and Mih71 have reported good short-term results (maintenance of reduction and improved forearm rotation) in 10 of 12 children with congenital radial head dislocation operated on between ages 7 months and 6 years. They reported that the most common finding was an interposition of the annular ligament, which they divided and then repaired in its anatomic position. Follow-up was short, however, averaging less than 2 years, with the longest being only 41 months.

The alternative to attempted reduction of congenital or infantile radial head dislocation is to accept the imposed disability (some limitation of forearm rotation, ranging from a few degrees to more than 90 degrees; occasional limitation of elbow motion; and infrequent pain) and proceed with radial head excision, if needed, at maturity.19–21,38,48,79 As noted in a long-term follow-up study,4 painful arthritis is typical only of the least common type I deformity. Relief of pain and cosmesis are more likely to be benefited from surgical excision; motion is seldom improved.4

TREATMENT OF SOFT TISSUE DYSPLASIAS

Treatment of most soft tissue problems at the elbow level is discussed in other chapters. Arthrogryposis, as well as other flaccid palsies, is covered in Chapter 71. Spastic neurogenic problems are discussed in Chapter 72, and nerve entrapment around the elbow is discussed in Chapter 80. Successful treatment for other soft tissue dysplasias at the elbow is rare. Aplasia cutis congenita has occurred in the elbow area. In the author’s experience, it was associated with scarring and hypoplasia of the regional forearm muscles plus reactive deformity of the underlying bones. Resurfacing with a skin and subcutaneous flap was eventually necessary, followed by tendon transfers, which in this instance were required to provide extensor function of the wrist and hand. Muscle anomalies may result in either mechanical problems (snapping or catching)16 or neurovascular entrapment, as discussed in Chapter 80.

TREATMENT OF COMBINED BONE AND SOFT TISSUE DYSPLASIAS

Pterygium cubitale remains an unsolved challenge. Attempts at treatment have included Z-plasty, skin grafts, and release of other tight structures. Improvement has been limited, and risks are high.23,24 Because there is no substantial report in the literature describing a reliable and useful method of treatment, no recommendations for surgical treatment are offered. Techniques of bone shortening to permit a greater safe excursion of the neurovascular structures or techniques of vascular and nerve grafting have been attempted, but adequate reporting is not yet available. The lengthening-stretching techniques of Ilizarov have been tried by a few investigators, so far with limited success. The hands in pterygium cubitale are often deficient also, but because limited excursion of the elbow is available in flexion, at least they are usually able to reach the upper trunk, the face, and the head.

In severe forms of ulnar dysplasia, the elbow often displays adequate range and stability. Occasionally, the displaced radial head is sufficiently limiting or symptom provoking so that treatment is offered. Although excision of the radial head and a sufficient portion of the shaft to resolve the mechanical block might suffice, the desire to stabilize and lengthen the forearm plus the fear of recurrent encroachment by the radial shaft usually lead to a recommendation for a one-bone forearm procedure (Fig. 13-15).9 This is carried out as follows:

In phocomelia, the elbow is seldom the site of the infrequent surgical attention given to this condition, but there may be an occasional indication for a one-bone forearm procedure or for simultaneous lengthening and stabilization at an unstable elbow segment.77

COMPLICATIONS

Overtreatment

In many cases, the severe upper limb anomaly, particularly if it is of the sporadic variety, is associated with a completely normal contralateral upper limb. In such cases, surgical treatment may have little effect on the long-term functional level of the patient.6 Therefore, it also is important to consider the likely practical gains from therapy before proposing an intervention. As has been noted, many synostotic forearms function well, even if in a poor position owing to compensatory hyper-rotation at the wrist. Such factors need to be considered carefully before embarking on a surgical adventure.

CONGENITAL ELBOW REDUX

Can a topic be brought to life, or at least reinvigorated? These questions arise as the authors peruse their prior efforts and the literature since those efforts and note that little has changed. There is still uncertainty regarding the relative incidence of the two most common congenital problems at the elbow, radial head subluxation or dislocation versus proximal radio-ulnar synostosis. Treatment for radial head dislocation still runs the gamut from waiting for symptoms/disability, then removing the radial head10 to open reduction, which may vary from removal of the annular ligament from the joint and reconstructing it in normal position to open reduction, corrective osteotomy of the ulna and reconstruction of an annular ligament, similar to the methods used for similar problems in old Monteggia injuries.85 Usually, radioulnar synostosis continues to be treated by corrective osteotomy, although new methods have been designed with osteotomies of both the radius (distally) and the ulna (proximally) with immediate correction if the deformity is not too severe59 or staged correction for the severe deformities.44 The venturesome among us are still, case by case, trying synostosis excision and interposition of various substances, recently using a vascular fascio-fat graft.34 The association of radial head subluxation or dislocation with other conditions continues to be newsworthy with new reports including congenital pseudarthrosis of the forearm41 treated by a one-bone forearm procedure in one case26 and treated by resection and internal fixation plus a vascularized fibular graft in another case.68 There are many reports of radial head subluxation or dislocation with other conditions17,40,73 and with paralyses.65 It is well known that shortening of the ulna from any cause risks of subluxation or dislocation of the radial head, but the association with radial longitudinal deficiency (44% of extremities with type 1 [more than 2 mm. shortening of the radius] radial deficiency32) is not as well known. However, it is certain that there is a familial component to some instances of radial head dislocation.69

So, what has changed in the last decade in this troublesome arena? Very little, and this is also troublesome. The potential for advances is overwhelming. Stem cell manipulation, embryonic and fetal alterations, early and late childhood intervention offer different and, as yet, minimally explored options. Solutions to the unsolved problems will involve both biologic and biotechnology approaches, and probably combinations of the two. The authors believe that this niche area has been dormant long enough and anticipate a need for both national and international interactions between all interested parties. In the next edition of this text, we hope to report on a tsunami of interactive investigations.

1 Abbott F.C. Congenital dislocation of radius. Lancet. 1892;1:800.

2 Almquist E.E., Gordon L.H., Blue A.L. Congenital dislocation of the head of the radius. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1969;51A:1118.

3 Bailey J.A. Elbow and other upper limb deformities in achondroplasia. Clin. Orthop. 1971;80:75.

4 Bell S.N., Morrey B.F., Bianco A.J. Chronic posterior subluxation and dislocation of the radial head. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73A:392.

5 Bert J.M., McElfresh E.C., Linscheid R.L. Rotary contracture of the forearm. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:1163.

6 Blair S.J., Swanson A.B., Swanson G.D. Evaluation of impairment of hand and upper extremity function. Instr. Course Lect. 1989;38:73.

7 Bottero L., Cinalli G., Labrune P., Lajeunie E., Renier D. Antley-Bixler syndrome. Description of two new cases and a review of the literature. Childs Nerv. Syst. 1997;13:275.

8 Brady L.P., Jewett E.L. A new treatment of radioulnar synostosis. South. Med. J. 1960;53:507.

9 Broudy A.S., Smith R.J. Deformities of the hand and wrist with ulnar deficiency. J. Hand Surg. 1979;4:304.

10 Campbell C.C., Waters P.M., Emans J.B. Excision of the radial head for congenital dislocation. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74:726.

11 Caravias D.E. Some observations on congenital dislocations of the head of the radius. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1957;39B:86.

12 Cleary J.E., Omer G.E. Congenital proximal radioulnar synostosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67A:539.

13 Crotti F.M., Mangiagalli E.P., Rampini P. Supracondyloid process and anomalous insertion of pronator teres as sources of median nerve neuralgia. J. Neurol. Sci. 1981;25:41.

14 Danielsson L.G., Theander G. Traumatic dislocation of the radial head at birth. Acta Radiol. 1981;22:379.

15 Dawson H.G.W. A congenital deformity of the forearm and its operative treatment. Br. Med. J. 1912;2:833.

16 Dreyfuss U., Kessler I. Snapping elbow due to dislocation of the medial head of the triceps. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1978;60B:56.

17 Eady J.L., Lundquist J.E., Grant R.E., Nagel A., Kim D.D. Congenital bowing of the ulna and aggressive fibromatosis. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 1991;83:978.

18 Falvo K.A., Freidenberg Z.B. Osteo-onychodysplasia. Clin. Orthop. 1971;81:130.

19 Ferguson A.B.Jr. Orthopedic surgery in infancy and childhood, 2nd ed. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins, Co., 1963.

20 Fox K.W., Griffen L.L. Congenital dislocation of the radial head. Clin. Orthop. 1960;18:234.

21 Goldner J.L., Lipton M.A. Congenital radioulnar synostosis: Diagnosis and treatment based on anatomic and functional assessment. Orthop. Trans. 1982;6:466.

22 Good C.J., Wicks M.H. Developmental posterior dislocation of the radial head. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1983;65B:64.

23 Green D.C. Operative Hand Surgery. New York: Churchill-Livingstone, 1982;267.

24 Green W.T., Mital M.A. Congenital radioulnar synostosis: Surgical treatment. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:738.

25 Gunn D.R., Pillay V.K. Congenital posterior dislocation of the head of the radius. Clin. Orthop. 1964;34:108.

26 Hadlow V. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the ulna: a case report. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1979;49:100.

27 Hansen O.H., Anderson N.O. Congenital radioulnar synostosis: Report of 37 cases. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1970;41:225.

28 Hoffer M.M. Joint motion limitation in newborns. Clin. Orthop. 1980;148:94.

29 Hollister D.W., Lachman R.S. Diastrophic dwarfism. Clin. Orthop. 1976;114:61.

30 Hunter A.G.W., Cox D.W., Rudd N.L. The genetics of and associated clinical findings in humeroradial synostosis. Clin. Genet. 1976;9:470.

31 Jacobsen S.T., Crawford A.H. Humeroradial synostosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1983;3:96.

32 James M.A., McCarroll H.R.Jr., Manske P.R. The spectrum of radial longitudinal deficiency: a modified classification. [see comment]. J. Hand Surg. 1999;24:1145.

33 Kaitila I.I., Leistei J.T., Rimoin D.L. Mesomelic skeletal dysplasia. Clin. Orthop. 1976;114:94.

34 Kanaya F., Ibaraki K. Mobilization of a congenital proximal radioulnar synostosis with use of a free vascularized fascio-fat graft [see comment]. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:1186.

35 Kasser J., Upton J. The shoulder, elbow and forearm in Apert syndrome. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1991;18:381.

36 Kelikian H. Congenital Deformities of the Hand and Forearm. Philadelphia: W B Saunders Co., 1974;310. 714, 902.

37 Kelikian H., Doumanian A. Swivel for proximal radioulnar synostosis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1957;39A:945.

38 Kelly D.W. Congenital dislocation of the radial head spectrum and natural history. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1981;1:245.

39 K’Iery L., Wouters H.W. Congenital ankylosis of joints. Arch. Chir. Neerl. 1971;2:173.

40 Lee D.Y., Cho T.J., Choi I.H., Chung C.Y., Yoo W.J., Kim J.H., Park Y.K. Clinical and radiological manifestations of osteogenesis imperfecta type V. J. Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:709.

41 Lee K.S., Lee S.H., Ha K.H., Lee S.J. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the ulna treated by free vascularized fibular graft—a case report. Hand Surg. 2000;5:61.

42 Leisti J., Lachman R.S., Rimoin D.L. Humeroradial ankylosis associated with other congenital defects (the boomerang arm sign). Birth Defects Orig. Artic. Ser. 1975;11:306.

43 Lenz W. Genetics and limb deficiencies. Clin. Orthop. 1980;148:9.

44 Lin H.H., Strecker W.B., Manske P.R., Schoenecker P.L., Seyer D.M. A surgical technique of radioulnar osteoclasis to correct severe forearm rotation deformities. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1995;15:53.

45 Lloyd-Roberts G.C., Bucknill T.M. Anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: Aetiology, natural history and management. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1977;59B:402.

46 Lorea P., Pajardi G., Medina J., Szabo Z., Foucher G. [The ulnar longitudinal deficiency: proposition of a des-criptive classification]. Chir. Main. 2004;23:294.

47 Mann, R. A., Johnston, J. O., and Ford, J.: Developmental posterior dislocation of the radial head: Ten cases resulting from ulnar hypoplasia. In 38th Annual Meeting of the Western Orthopedic Association. 1974. Honolulu, Hawaii.

48 Mardam-Bey T., Ger E. Congenital radial head dislocation. J. Hand Surg.. 1979;4:316.

49 Masuko T., Kato H., Minami A., Inoue M., Hirayama T. Surgical treatment of acute elbow flexion contracture in patients with congenital proximal radioulnar synostosis. A report of two cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am.. 2004;86-A:1528.

50 McCredie J. Congenital fusion of bones: Radiology, embryology, and pathogenesis. Clin. Radiol.. 1975;26:47.

51 McFarland B. Congenital dislocation of the head of the radius. Br. J. Surg.. 1936;24:41.

52 McIntyre J.D., Benson M.K. An aetiological classification for developmental synostoses at the elbow. J. Pediatr. Orthop.. 2002;11:313.

53 McIntyre J.D., Brooks A., Benson M.K. Humeroradial synostosis and the multiple synostosis syndrome: case report. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 2003;12:192.

54 McKusick V. Mendelian Inheritance in Man, 6th ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1983.

55 Mital M.A. Congenital radioulnar synostosis and congenital dislocation of the radial head. Orthop. Clin. North. Am.. 1976;7:375.

56 Miura T. Congenital dislocation of the radial head. J. Hand Surg.. 1990;15B:377.

57 Mnaymneh W.A. Congenital radiohumeral synostosis. A case report. Clin Orthop.. 1978;131:183.

58 Murakami Y., Komiyama Y. Hypoplasia of the trochlea and the medial epicondyle of the humerus associated with ulnar neuropathy. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1978;60B:225.

59 Murase T., Tada K., Yoshida T., Moritomo H. Derotational osteotomy at the shafts of the radius and ulna for congenital radioulnar synostosis. J. Hand Surg. Am.. 2003;28:133.

60 Murphy H.S., Hansen C.G. Congenital humeroradial synostosis. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1945;27:712.

61 Ogden J.A. Skeletal Injury in the Child. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1982;319.

62 Ogino T., Hikino K. Congenital radioulnar synostosis: Compensatory rotation around the wrist and rotation osteotomy. J. Hand Surg.. 1987;12B:173.

63 Pfeiffer R. Die angeborene Verrenkung des Speichenkopfchens als Teilerscheinung anderer kongenitaler Ellenbogengelenkmissbildungen. Mensch Vererb Konstitutionslehre. 1938;21:530.

64 Phillips S. Congenital dislocation of radii. Br. Med. J.. 1883;1:773.

65 Pletcher D.F., Hoffer M.M., Koffman D.M. Non-traumatic dislocation of the radial head in cerebral palsy. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1976;58:104.

66 Pouliquen J.C., Pauthier F., Kassis B., Glorion C. Bilateral congenital pseudarthrosis of the olecranon. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B. 1997;6:223.

67 Powers C.A. Congenital dislocations of the radius. J. A. M. A.. 1903;41:165.

68 Ramelli G.P., Slongo T., Tschäppeler H., Weis J. Congenital pseudarthrosis of the ulna and radius in two cases of neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatr. Surg. Intern.. 2001;17:239.

69 Reichenbach H., Hormann D., Theile H. Hereditary congenital posterior dislocation of radial heads. Am. J. Med. Genet.. 1995;55:101.

70 Ryan J.R. The relationship of the radial head to radial neck diameters in fetuses and adults with reference to radial head subluxation in children. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1969;51A:781.

71 Sachar K., Mih A.D. Congenital radial head dislocations. Hand Clin.. 1998;14:39.

72 Salter R., Zaltz C. Anatomic investigations of the mechanism of injury and pathologic anatomy of “pulled elbow” in children. Clin. Orthop. 1971;77:134.

73 Sanatkumar S., Rajagopalan N., Mallikarjunaswamy B., Srinivasalu S., Sudhir N.P., Usha K. Benign fibrous histiocytoma of the distal radius with congenital dislocation of the radial head: a case report. J. Orthop. Surg. (Hong Kong). 2005;13:83.

74 Sato K., Miura T. Hypoplasia of the humeral trochlea. J. Hand Surg. 1990;15A:1004.

75 Schubert J.J. Dislocation of the radial head in the newborn infant. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1965;47A:1019.

76 Simmons B.P., Southmayd W.W., Riseborough E.J. Congenital radioulnar synostosis. J. Hand Surg. 1983;9:829.

77 Smith R.J., Lipke R.W. Treatment of congenital deformities of the hand and forearm, Part II. N. Engl. J. Med. 1979;300:402.

78 Smith R.W. Congenital luxations of the radius. Dublin Q. J. Med. Sci. 1852;13:208.

79 Southmayd W., Ehrlich M.G. Idiopathic subluxation of the radial head. Clin. Orthop. 1976;121:271.

80 Stone C.A. Subluxation of the head of the radius: Report of a case and anatomical experiments. J. A. M. A. 1916;1:28.

81 Struthers J. A peculiarity of the humerus and humeral artery. Month. J. Med. Sci. 1848;28:264.

82 Temtamy S.A., McKusick V.A. Carpal/tarsal synostosis. Birth Defects. 1978;14:502.

83 Tubiana R. The Hand. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co., 1981.

84 Uthoff K., Bosch U. Die proximale radioulnare synostose im rahmen des fetalen alkoholsyndrom. Unfallchirug. 1997;100:678.

85 Wang M.N., Chang W.N. Chronic posttraumatic anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: thirteen cases treated by open reduction, ulnar osteotomy, and annular ligament reconstruction through a Boyd incision. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2006;20:1-5.

86 Wiley J.J., Loehr J., McIntyre W. Isolated dislocation of the radial head. Orthop. Rev. 1991;20:973.

87 Williams P.F. The elbow in arthrogryposis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55B:834.

88 Windfeld P. On congenital and acquired luxation of the capitellum radii with discussion of some associated problems. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1946;16:126.

89 Wood V.E., Sauser D.D., O’Hara R.C. The shoulder and elbow in Apert syndrome. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1995;15:648.

90 Wynne-Davies R. Heritable Disorders in Orthopaedic Practice. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1973.