CHAPTER 16 Congenital Abnormalities and Dysmorphic Syndromes

The formation of a human being, a process sometimes known as morphogenesis, involves extremely complicated cell biology that, though only partially understood, is beginning to yield its mysteries (see Chapter 6). Given the complexity, it is not surprising that on occasion it goes wrong. Nor is it surprising that in many congenital abnormalities genetic factors can clearly be implicated. Approximately 2400 dysmorphic syndromes are described that are thought to be due to molecular pathology in single genes, and for at least 500 the genes have been identified and more than 200 mapped. A further 500 or so sporadically occurring syndromes are recognized, for which the precise cause remains elusive. In this chapter, we shall consider the overall impact of abnormalities in morphogenesis by reviewing the following.

Incidence

Newborn Infants

Surveys reviewing the incidence of both major and minor anomalies in newborn infants have been undertaken in many parts of the world. A major anomaly can be defined as one that has an adverse outcome on either the function or the social acceptability of the individual (Table 16.1). In contrast, minor abnormalities are of neither medical nor cosmetic importance (Box 16.1). However, the division between major and minor abnormalities is not always straightforward; for instance, an inguinal hernia occasionally leads to strangulation of bowel and always requires surgical correction, so there is a risk of serious sequelae.

Table 16.1 Examples of Major Congenital Structural Abnormalities

| System and Abnormality | Incidence per 1000 Births |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 10 |

| Ventricular septal defect | 2.5 |

| Atrial septal defect | 1 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 1 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 1 |

| Central nervous system | 10 |

| Anencephaly | 1 |

| Hydrocephaly | 1 |

| Microcephaly | 1 |

| Lumbosacral spina bifida | 2 |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 |

| Cleft lip/palate | 1.5 |

| Diaphragmatic hernia | 0.5 |

| Esophageal atresia | 0.3 |

| Imperforate anus | 0.2 |

| Limb | 2 |

| Transverse amputation | 0.2 |

| Urogenital | 4 |

| Bilateral renal agenesis | 2 |

| Polycystic kidneys (infantile) | 0.02 |

| Bladder exstrophy | 0.03 |

These surveys have consistently shown that 2% to 3% of all newborns have at least one major abnormality apparent at birth. The true incidence, taking into account abnormalities that present later in life, such as brain malformations, is probably close to 5%. Minor abnormalities are found in approximately 10% of all newborns. If two or more minor abnormalities are present in a newborn, there is a 10% to 20% risk that the baby will also have a major malformation.

Childhood Mortality

Collating the incidence data on abnormalities noted in early spontaneous miscarriages and newborns, at least 15% of all recognized human conceptions are structurally abnormal (Table 16.2), and genetic factors are probably implicated in at least 50% of these.

| Incidence | (%) |

|---|---|

| Spontaneous Miscarriages | |

| First trimester | 80–85 |

| Second trimester | 25 |

| All Babies | |

| Major abnormality apparent at birth | 2–3 |

| Major abnormality apparent later | 2 |

| Minor abnormality | 10 |

| Death in perinatal period | 25 |

| Death in first year of life | 25 |

| Death at 1–9 years | 20 |

| Death at 10–14 years | 7.5 |

Definition and Classification of Birth Defects

Single Abnormalities

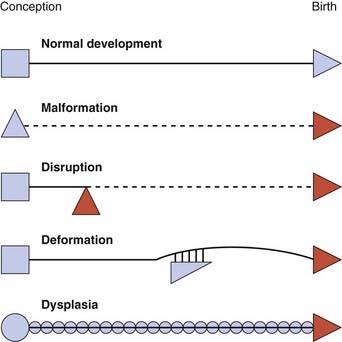

Single abnormalities may have a genetic or non-genetic basis. The system of terms used helps us to understand the different mechanisms that might be implicated, and these can be illustrated in schematic form (Figure 16.1).

Malformation

A malformation is a primary structural defect of an organ, or part of an organ, that results from an inherent abnormality in development. This used to be known as a primary or intrinsic malformation. The presence of a malformation implies that the early development of a particular tissue or organ has been arrested or misdirected. Common examples include congenital heart abnormalities such as ventricular or atrial septal defects, cleft lip and/or palate, or neural tube defects (Figure 16.2). Most malformations involving only a single organ show multifactorial inheritance, implying an interaction of gene(s) with other factors (p. 143). Multiple malformations are more likely to be due to chromosomal abnormalities but may be due to single gene mutations.

Disruption

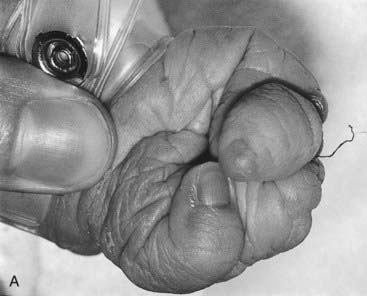

The term disruption refers to an abnormal structure of an organ or tissue as a result of external factors disturbing the normal developmental process. This used to be known as a secondary or extrinsic malformation, and includes ischemia, infection, and trauma. An example of a disruption is the effect seen on limb development when a strand or band of amnion becomes entwined around a baby’s forearm or digits (Figure 16.3). By definition a disruption is not genetic, although occasionally genetic factors can predispose to disruptive events. For example, a small proportion of amniotic bands are caused by an underlying genetically determined defect in collagen that weakens the amnion, making it more liable to tear or rupture spontaneously.

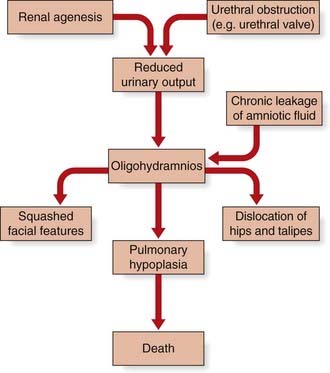

Deformation

A deformation is a defect resulting from an abnormal mechanical force that distorts an otherwise normal structure. Examples include dislocation of the hip and mild ‘positional’ talipes (‘clubfoot’) (Figure 16.4) resulting from reduced amniotic fluid (oligohydramnios) or intrauterine crowding from twinning or a structurally abnormal uterus. Deformations usually occur late in pregnancy and convey a good prognosis with appropriate treatment—for instance, gentle splinting for talipes, because the underlying organ is fundamentally normal in structure.

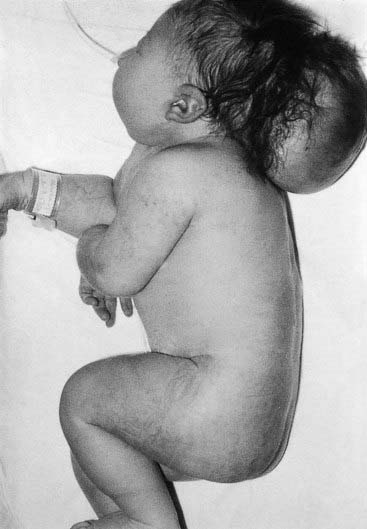

Dysplasia

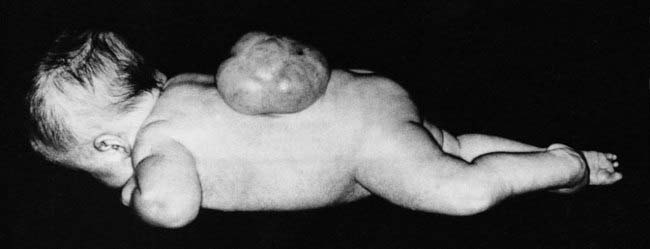

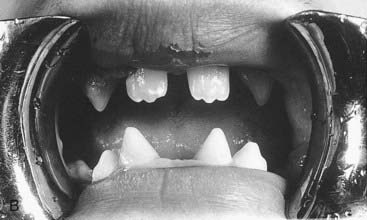

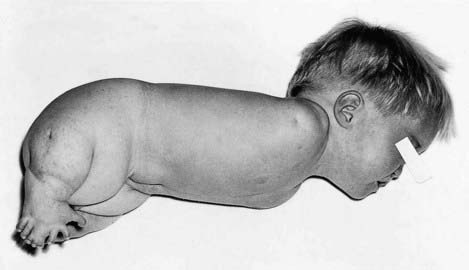

A dysplasia is an abnormal organization of cells into tissue. The effects are usually seen wherever that particular tissue is present. For example, in a skeletal dysplasia such as thanatophoric dysplasia, which is caused by mutations in FGFR3 (p. 93), almost all parts of the skeleton are affected (Figure 16.5). Similarly, in an ectodermal dysplasia, widely dispersed tissues of ectodermal origin, such as hair, teeth, skin, and nails, are involved (Figure 16.6). Most dysplasias are caused by single-gene defects and are associated with high recurrence risks for siblings and/or offspring.

Multiple Abnormalities

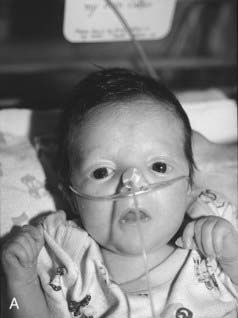

Sequence

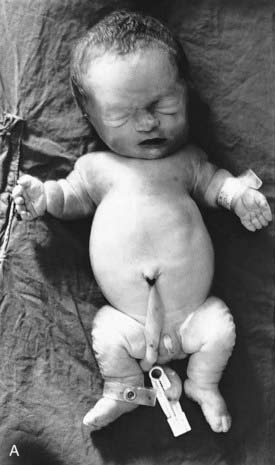

This concept describes the findings that occur as a consequence of a cascade of events initiated by a single primary factor and may result in a single organ malformation. In the ‘Potter’ sequence, chronic leakage of amniotic fluid or defective fetal urinary output results in oligohydramnios (Figure 16.7). This, in turn, leads to fetal compression, resulting in squashed facial features, dislocation of the hips, talipes, and pulmonary hypoplasia (Figure 16.8), usually resulting in neonatal death from respiratory failure.

Syndrome

In practice the term syndrome is used very loosely (e.g., the amniotic band ‘syndrome’), but in theory it should be reserved for consistent and recognizable patterns of abnormalities for which there will often be a known underlying cause. These underlying causes can include chromosome abnormalities, as in Down syndrome, or single gene defects, as in the Van der Woude syndrome, in which cleft lip and/or palate occurs in association with pits in the lower lip (Figure 16.9).

Several thousand multiple malformation syndromes are recognized, and their clinical study has been the discipline of dysmorphology. Clinical diagnosis has been greatly helped by the development of computerized databases (see Appendix) with a search facility based on key abnormal features. Even with the help of this extremely valuable diagnostic tool, there are many dysmorphic children for whom no diagnosis is reached, so that it can be very difficult to provide accurate information about the likely prognosis and recurrence risk (p. 266). The technique of microarray-CGH (p. 281) is making inroads into this large group of undiagnosed patients.

Association

This classification of birth defects is not perfect—it is far from being either fully comprehensive or mutually exclusive. For example, bladder outflow obstruction caused by a primary malformation such as a urethral valve will result in the oligohydramnios or Potter sequence, leading to secondary deformations such as dislocation of the hip and talipes. To complicate matters further, the absence of both kidneys, which will result in the same sequence of events, is usually erroneously referred to as Potter syndrome. Despite this semantic confusion, classifications can aid understanding of causes and recurrence risks (Chapter 17).

Genetic Causes of Malformations

There are many recognized causes of congenital abnormality, although it is notable that in up to 50% of all cases no clear explanation can be established (Table 16.3).

| Cause | % |

|---|---|

| Genetic | 30–40 |

| Chromosomal | 6 |

| Single gene | 7.5 |

| Multifactorial | 20–30 |

| Environmental | 5–10 |

| Drugs and chemicals | 2 |

| Infections | 2 |

| Maternal illness | 2 |

| Physical agents | 1 |

| Unknown | 50 |

| Total | 100 |

Chromosome Abnormalities

These account for approximately 6% of all recognized congenital abnormalities. As a general rule, any perceptible degree of autosomal imbalance, such as duplication, deletion, trisomy, or monosomy, will result in severe structural and developmental abnormality, which may lead to early miscarriage. Common chromosome syndromes are described in Chapter 18. It is not known whether malformations caused by a significant chromosome abnormality, such as a trisomy, are the result of dosage effects of the individual genes involved (‘additive’ model) or general developmental instability caused by a large number of abnormal developmental gene products (‘interactive’ model).

Single-Gene Defects

These account for 7% to 8% of all congenital abnormalities. Some of these are isolated—i.e., they involve only one organ or system (Table 16.4). Other single-gene defects result in multiple congenital abnormality syndromes involving many organs or systems that do not have any obvious underlying embryological relationship. For example, ectrodactyly (Figure 16.10) in isolation can be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait, occasionally autosomal recessive, and rarely X-linked. It can also occur as one manifestation of the EEC syndrome (ectodermal dysplasia, ectrodactyly and cleft lip/palate), which follows autosomal dominant inheritance. Therefore different mutations, allelic or non-allelic, can cause similar or identical malformations.

Table 16.4 Congenital Abnormalities that can be Caused by Single-Gene Defects

| Inheritance | Abnormalities | |

|---|---|---|

| Isolated | ||

| central nervous system | ||

| Hydrocephalus | XR | |

| Megalencephaly | AD | |

| Microcephaly | AD/AR | |

| ocular | ||

| Aniridia | AD | |

| Cataracts | AD/AR | |

| Microphthalmia | AD/AR | |

| limb | ||

| Brachydactyly | AD | |

| Ectrodactyly | AD/AR/XR | |

| Polydactyly | AD | |

| other | ||

| Infantile polycystic | AR kidneys | |

| Syndromes | ||

| Apert | AD | Craniosynostosis, syndactyly |

| EEC | AD | Ectodermal dysplasia, ectrodactyly, cleft lip/palate |

| Meckel | AR | Encephalocele, polydactyly, polycystic kidneys |

| Roberts | AR | Cleft lip/palate, phocomelia |

| Van der Woude | AD | Cleft lip/palate, lip pits |

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; XR, X-linked recessive.

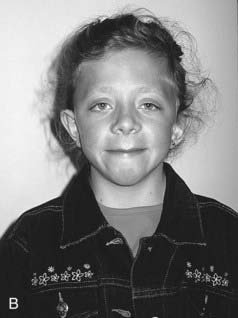

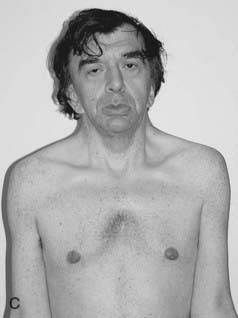

Noonan Syndrome

First described by Noonan and Ehmke in 1963, this well-known condition has incidence that may be as high as 1 : 2000 births, with equal sex ratio. The features resemble those of Turner syndrome in females—short stature, neck webbing, increased carrying angle at the elbow and congenital heart disease. Pulmonary stenosis is the most common lesion but atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, and occasionally hypertrophic cardiomyopathy occur. A characteristic mild pectus deformity may be seen, and the face shows hypertelorism, down-slanting palpebral fissures, and low-set ears (Figure 16.11). Some patients have a mild bleeding diathesis, and learning difficulties occur in about one-quarter.

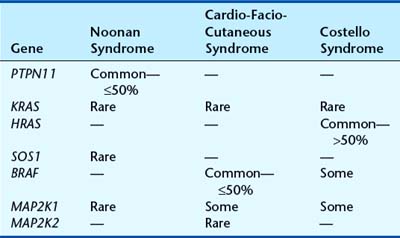

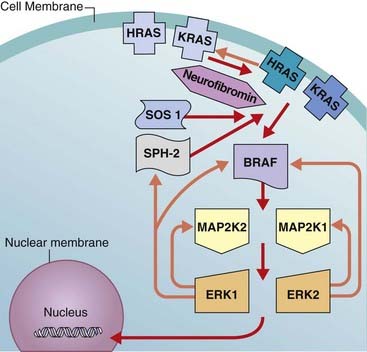

In a three-generation Dutch family, Noonan syndrome (NS) was mapped to 12q22 in 1994, but it was not until 2001 that mutations were identified in the protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor-type, 11 (PTPN11) gene. Attention has turned rapidly to phenotype–genotype correlation, and mutation-positive cases have a much higher frequency of pulmonary stenosis than mutation-negative cases, and very few mutations have been found in patients with cardiomyopathy. However, facial features are similar, whether or not a mutation is found. Mutations in PTPN11 account for about half of all cases of NS. Mutations in the SOS1, SHOC2, KRAS, and MAPZK1 genes have been found in a small proportion of PTPN11-negative cases. These genes belong to the same pathway, known as RAS-MAPK. The protein product of PTPN11 is SHP-2 and this, together with SOS1, positively transduces signals to Ras-GTP, a downstream effector (Figure 16.12). The KRAS mutations in NS appear to lead to K-ras proteins with impaired responsiveness to GTPase activating proteins (p. 213). Neurofibromatosis, the most common of this group, is dealt with in Chapter 18 (p. 298).

FIGURE 16.12 The RAS-MAPK pathway. HRAS and KRAS are activated by SPH-2 and SOS1 (red arrows). Orange arrows = inhibition. The pathway is dysregulated by mutations in key components, resulting in the distinct but related phenotypes of Noonan syndrome, CFC syndrome, Costello syndrome, and neurofibromatosis (see Table 16.5). Neurofibromin is a GAP (GTPase activating) protein that functions as a tumor-suppressor. Mutant RAS proteins display impaired GTPase activity and are resistant to GAPs. The effect is for RAS to bind GTP, which results in activation of the pathway (gain of function).

For years dysmorphologists recognized overlapping features between NS and the rarer conditions known as cardio-facio-cutaneous and Costello syndromes. These conditions are now recognized to form part of a spectrum of disorders explained by mutations in different components of the RAS-MAPK pathway, with each syndrome displaying considerable genetic heterogeneity (Table 16.5). Many of the mutations are gain-of-function missense mutations, which may explain the increase in solid tumors in Costello syndrome as well as cellular proliferation in some tissues in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome (e.g., hyperkeratosis). The effect is for RAS to bind GTP, which results in activation of the pathway (gain-of-function). Neurofibromin is a GTPase activating protein, and functions as a tumor-suppressor.

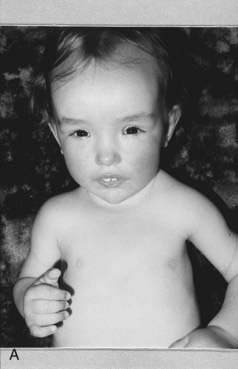

Sotos Syndrome

First described in 1964, this is one of the ‘overgrowth’ syndromes, previously known as cerebral gigantism. Birth weight is usually increased and macrocephaly noted. Early feeding difficulties and hypotonia may prompt many investigations and there is often motor delay and ataxia. Height progresses along the top of, or above, the normal centile lines, but final adult height is not necessarily markedly increased. Advanced bone age may be present, as well as large hands and feet, and the cerebral ventricles may be mildly dilated on imaging. The face is characteristic (Figure 16.13), with a high prominent forehead, hypertelorism with down-slanting palpebral fissures, a characteristic nose in early childhood, and a long pointed chin. Scoliosis develops in some cases during adolescence. Parent–child transmission is rare, probably because most patients have learning difficulties. However, the author has seen a three-generation family including individuals with above average intelligence.

Among patients with Sotos syndrome reported to have balanced chromosome translocations were two with breakpoints at 5q35. From these crucial patients a Japanese group in 2002 went on to identify a 2.2-Mb deletion in a series of Sotos syndrome cases. The deletion takes out a gene called NSD1, an androgen receptor-associated co-regulator with 23 exons. The Japanese found a small number of frameshift mutations in their patients but, interestingly, a study of European cases found that mutations were far more common than deletions. For the large majority of cases the mutations and deletions occur de novo.

Multifactorial Inheritance

This accounts for the majority of congenital abnormalities in which genetic factors can clearly be implicated. These include most isolated (‘non-syndromal’) malformations involving the heart, central nervous system, and kidneys (Box 16.2). For many of these conditions, empirical risks have been derived (p. 346) based on large epidemiological family studies, so that it is usually possible to provide the parents of an affected child with a clear indication of the likelihood that a future child will be similarly affected. Risks to the offspring of patients who were themselves treated successfully in childhood are becoming available. These are usually similar to the risks that apply to siblings, as would be predicted by the multifactorial model (p. 143).

Genetic Heterogeneity

It has long been recognized that specific congenital malformations can have many different causes (p. 346), hence the importance of trying to distinguish between syndromal and isolated cases. This causal diversity has become increasingly apparent as developments in molecular biology have led to the identification of highly conserved families of genes that play crucial roles in early embryogenesis.

This subject is discussed at length in Chapter 6. In the current chapter, two specific malformations, holoprosencephaly and neural tube defects, will be considered to demonstrate the rate of progress in this field and the extent of the challenge that lies ahead.

Holoprosencephaly

This severe and often fatal malformation is caused by a failure of cleavage of the embryonic forebrain or prosencephalon. Normally this divides transversely into the telencephalon and the diencephalon. The telencephalon divides in the sagittal plane to form the cerebral hemispheres and the olfactory tracts and bulbs. The diencephalon develops to form the thalamic nuclei, the pineal gland, the optic chiasm, and the optic nerves. In holoprosencephaly, there is incomplete or partial failure of these developmental processes, and in the severe alobar form this results in an abnormal facial appearance (see Figure 6.7, p. 88) with profound neurodevelopmental impairment.

Etiologically, holoprosencephaly can be classified as chromosomal, syndromal, or isolated. Chromosomal causes account for around 30% to 40% of all cases, with the most common abnormality being trisomy 13 (p. 275). Other chromosomal causes include deletions of 18p, 2p21, 7q36, and 21q22.3, duplication of 3p24-pter, duplication or deletion of 13q, and triploidy (p. 276). Syndromal causes of holoprosencephaly are numerous and include relatively well known conditions such as the deletion 22q11 (DiGeorge) syndrome (p. 282) and a host of much rarer multiple malformation syndromes, some of which show autosomal recessive inheritance. One of these, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (p. 87), is associated with low levels of cholesterol; this is relevant in that it is known that cholesterol is necessary for normal functioning of the sonic hedgehog pathway (p. 86).

That so many familial cases remain unexplained indicates that more holoprosencephaly genes await identification. Causal heterogeneity is further illustrated by its association with poorly controlled maternal diabetes mellitus (p. 261).

Neural Tube Defects

Neural tube defects (NTDs), such as spina bifida and anencephaly, illustrate many of the underlying principles of multifactorial inheritance and emphasize the importance of trying to identify possible adverse environmental factors. These conditions result from defective closure of the developing neural tube during the first month of embryonic life. A defect occurring at the upper end of the developing neural tube results in either exencephaly/anencephaly or an encephalocele (Figure 16.14). A defect occurring at the lower end of the developing neural tube leads to a spinal lesion such as a lumbosacral myelocele or meningomyelocele (see Figure 16.2), and a defect involving the head plus cervical and thoracic spine leads to craniorachischisis. These different entities relate to the different embryological closure points of the neural tube. Most NTDs have serious consequences. Anencephaly and craniorachischisis are not compatible with survival for more than a few hours after birth. Large lumbosacral lesions usually cause partial or complete paralysis of the lower limbs with impaired bladder and bowel continence.

No single NTD susceptibility genes have been identified in humans, although there is some evidence that the common 677C > T polymorphism in the Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene can be a susceptibility factor in some populations. Reduction in MTHFR activity results in decreased plasma folate levels, which are known to be causally associated with NTDs (see the following section). Research efforts have also focused on developmental genes, such as the PAX family (p. 91), which are expressed in the embryonic neural tube and vertebral column. In mouse models, about 80 genes have been linked to exencephaly, about 20 genes to lumbosacral meningomyelocele, and about 5 genes to craniorachischisis. One example is an interaction between mutations of PAX1 and the Platelet-derived growth factor α gene (PDGFRA) that results in severe NTDs in 100% of double-mutant embryos. This rare example of digenic inheritance (p. 119) serves as a useful illustration of the difficulties posed by a search for susceptibility genes in a multifactorial disorder. However, to date there have been no equivalent breakthroughs in understanding the processes in human NTDs.

Environmental factors include poor socioeconomic status, multiparity, and valproic acid embryopathy (p. 261). Firm evidence has also emerged that periconceptional multivitamin supplementation reduces the risk of recurrence by a factor of 70% to 75% when a woman has had one affected child. Several studies have shown that folic acid is likely to be the effective constituent in multivitamin preparations. In both the United Kingdom and the United States, it is recommended that all women who have had a previous child with a NTD should take 4 to 5 mg folic acid daily both before and during the early stages of all subsequent pregnancies. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, it has been recommended that all women who are trying to conceive should take 0.4 mg folic acid daily. In the United States, where bread is fortified with folic acid, this recommendation applies to all women of reproductive age throughout their reproductive years. In the United Kingdom, this recommendation has not as yet resulted in a noticeable decline in the incidence of NTDs.

Environmental Agents (Teratogens)

Drugs and Chemicals

Drugs and chemicals with a proven teratogenic effect in humans are listed in Table 16.6. These may account for approximately 2% of all congenital abnormalities.

| Drug | Effects |

|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors | Renal dysplasia |

| Alcohol | Cardiac defects, microcephaly, characteristic facies |

| Chloroquine | Chorioretinitis, deafness |

| Diethylstilbestrol | Uterine malformations, vaginal adenocarcinoma |

| Lithium | Cardiac defects (Ebstein anomaly) |

| Phenytoin | Cardiac defects, cleft palate, digital hypoplasia |

| Retinoids | Ear and eye defects, hydrocephalus |

| Streptomycin | Deafness |

| Tetracycline | Dental enamel hypoplasia |

| Thalidomide | Phocomelia, cardiac and ear abnormalities |

| Valproic acid | Neural tube defects, clefting, limb defects, characteristic facies |

| Warfarin | Nasal hypoplasia, stippled epiphyses |

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme.

The Thalidomide Tragedy

The most characteristic abnormality caused by thalidomide was phocomelia (Figure 16.15). This is the name given to a limb that is malformed due to absence of some or all of the long bones, with retention of digits giving a ‘flipper’ or ‘seal-like’ appearance. Other external abnormalities included ear defects, microphthalmia and cleft lip/palate. In addition, approximately 40% died in early infancy from severe internal abnormalities affecting the heart, kidneys, or gastrointestinal tract. Some ‘thalidomide babies’ have grown up and had children of their own, and in some cases these offspring have also had similar defects. It is therefore most likely, not surprisingly, that thalidomide was wrongly blamed in a proportion of cases that were in fact from single-gene conditions following autosomal dominant inheritance (e.g., SALL4 mutations [see Figure 6.21, C, p. 99] in Okihiro syndrome).

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

Children born to mothers who have consistently consumed large quantities of alcohol during pregnancy tend to show a degree of microcephaly, a distinctive facial appearance with short palpebral fissures, and a long smooth philtrum (Figure 16.16). They also show developmental delay with hyperactivity and clumsiness. This condition is referred to as fetal alcohol syndrome, but if the physical aspects are lacking the term ‘alcohol-related neurodevelopmental defects’ may be applied. There is uncertainty about the ‘safe’ level of alcohol consumption in pregnancy and there is evidence that mild-to-moderate ingestion can be harmful. Generally, total abstinence from alcohol is advised throughout pregnancy.

Maternal Infections

Several infectious agents can interfere with embryogenesis and fetal development (Table 16.7). The developing brain, eyes, and ears are particularly susceptible to damage by infection.

| Infection | Effects |

|---|---|

| Viral | |

| Cytomegalovirus | Chorioretinitis, deafness, microcephaly |

| Herpes simplex | Microcephaly, microphthalmia |

| Rubella | Microcephaly, cataracts, retinitis, cardiac defects |

| Varicella zoster | Microcephaly, chorioretinitis, skin defects |

| Bacterial | |

| Syphilis | Hydrocephalus, osteitis, rhinitis |

| Parasitic | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Hydrocephalus, microcephaly, cataracts, chorioretinitis, deafness |

Rubella

The rubella virus, which damages 15% to 25% of all babies infected during the first trimester, causes cardiovascular malformations such as patent ductus arteriosus and peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis. Congenital rubella infection can be prevented by the widespread use of immunization programs based on administration of either the measles, mumps, rubella vaccine in early childhood or rubella vaccine alone to young adult women.

Physical Agents

Ionizing Radiation

Heavy doses of ionizing radiation, far in excess of those used in routine diagnostic radiography, can cause microcephaly and ocular defects in the developing fetus. The most sensitive time of exposure is 2 to 5 weeks post-conception. Ionizing radiation can also have mutagenic (p. 26) and carcinogenic effects and, although the risks associated with low-dose diagnostic procedures are minimal, radiography should be avoided during pregnancy if possible.

Maternal Illness

Several maternal illnesses are associated with an increased risk of an untoward pregnancy outcome.

Phenylketonuria

Another maternal metabolic condition that conveys a risk to the fetus is untreated phenylketonuria (p. 167). A high serum level of phenylalanine in a pregnant woman with phenylketonuria will almost invariably result in serious damage (e.g., mental retardation). Structural abnormalities may include microcephaly and congenital heart defects. All women with phenylketonuria should be strongly advised to adhere to a strict and closely monitored low phenylalanine diet before and throughout pregnancy.

Maternal Epilepsy

There is a large body of literature devoted to the question of maternal epilepsy, the link with congenital abnormalities, and the teratogenic effects of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). The largest and best controlled studies suggest that maternal epilepsy itself is not associated with an increased risk of congenital abnormalities. However, all studies have shown an increased incidence of birth defects in babies exposed to AEDs. The risks are in the region of 5% to 10%, which is two to five times the background population risk. These figures apply mainly to single drug therapy, and may be doubled if the fetus is exposed to more than one AED. Some drugs are more teratogenic than others, with the highest risks applying to sodium valproate. The range of abnormalities occurring in the ‘fetal anticonvulsant syndromes’ (FACS) are wide, including neural tube defect (about 2%), oral clefting, genitourinary abnormalities such as hypospadias, congenital heart disease, and limb defects. The abnormalities themselves are not specific to FACS, and making a diagnosis in an individual case can therefore be difficult. Sometimes characteristic facial features are seen, particularly in fetal valproate syndrome (Figure 16.17).

Malformations of Unknown Cause

Symmetry and Asymmetry

When trying to assess whether a birth defect is genetic or non-genetic, it may be helpful to consider aspects of symmetry. As a very broad generalization, symmetrical and midline abnormalities frequently have a genetic basis. Asymmetrical defects are less likely to have a genetic basis. In the examples shown in Figure 16.18, the child with cleidocranial dysplasia (Figure 16.18, A) has symmetrical defects (absent or hypoplastic clavicles) and other features indicating a generalized tissue disorder that is overwhelmingly likely to have a genetic basis. The striking asymmetry of the limb deformities in Figure 16.18, B is likely to have a non-genetic basis.

Counseling

In cases where the precise diagnosis is uncertain, an assessment of symmetry and midline involvement may be helpful for genetic counseling. Although it may be very frustrating that no detailed explanation is possible, in many cases reassurance about a low recurrence risk in a future pregnancy can be given, based on empirical data. It is worth noting that this does not necessarily mean that genetic factors are irrelevant. Some ‘unexplained’ malformations and syndromes could well be due to new dominant mutations (p. 113), submicroscopic microdeletions (p. 280), or uniparental disomy (p. 121). All of these would convey negligible recurrence risks to future siblings, although those cases from new mutations or microdeletions would be associated with a significant risk to the offspring of affected individuals. There is optimism that molecular techniques will provide at least some of the answers to these many unresolved issues.

Aase J. Diagnostic dysmorphology. London: Plenum; 1990.

A detailed text of the art and science of dysmorphology.

Hanson JW. Human teratology. In: Rimoin DL, Connor JM, Pyeritz RE, editors. Principles and practice of medical genetics. 3rd edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:697-724.

A comprehensive, balanced overview of known and suspected human teratogens.

Jones KL. Smith’s recognizable patterns of human malformation, 6th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006.

The standard pediatric textbook guide to syndromes.

Smithells RW, Newman CGH. Recognition of thalidomide defects. J Med Genet. 1992;29:716-723.

A comprehensive account of the spectrum of abnormalities caused by thalidomide.

Spranger J, Benirschke K, Hall JG, et al. Errors of morphogenesis: concepts and terms. Recommendations of an international working group. J Pediatr. 1982;100:160-165.

Stevenson RE, Hall JG, Goodman RM. Human malformations and related anomalies. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993.

The definitive guide, in two volumes, to human malformations.

Elements