Confusion and delirium

Introduction

The manifestation of any confusional state or delirium depends on the premorbid state of the patient. A patient with a pre-existing higher function deficit will be more prone to florid delirium than someone with normal higher function. Common causes of confusion include metabolic illness, drug toxicity, systemic infections and CNS pathology such as encephalitis or subdural haematoma. Difficult to diagnose but treatable causes are non-convulsive status epilepticus (uncommon) and autoimmune ‘limbic’ encephalitis (rare) which is often a paraneoplastic condition (p. 96).

Clinical features

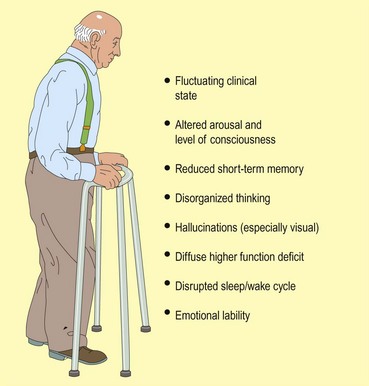

Delirium comes on within hours to a few weeks (Fig. 1). There is a prominent fluctuation in symptomatology. Patients are distractible and disorganized in thinking. They are slow to respond and may find it difficult to answer questions without going off at a tangent. Their speech may be slurred. They may report hallucinations which are often visual, florid and menacing. Their sleep pattern becomes disrupted with sleeping in the day and waking at night. Most patients become physically slowed. They usually have a prominent loss of short-term memory, reflecting their poor attention. Patients become emotionally labile, being tearful or frightened, or become angry and agitated relatively easily. Some patients can become hyperactive and very agitated.

Differential diagnosis

Assessment

Prior level of mental function and pattern of behaviour. Were there any clues to suggest an impaired premorbid intellect?

Prior level of mental function and pattern of behaviour. Were there any clues to suggest an impaired premorbid intellect? Any coexistent medical problems, particularly diabetes, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, cardiac or respiratory problems.

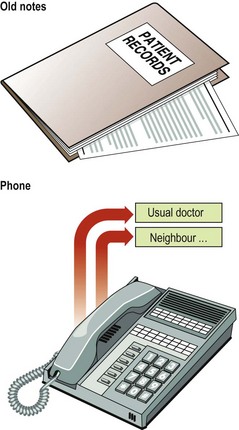

Any coexistent medical problems, particularly diabetes, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease, cardiac or respiratory problems.This will often be available from the spouse, another relative or carer. If there is no-one with the patient who can give the essential background information then it needs to be sought from neighbours, the local doctor or anyone else who might be able to provide it, or from any previous medical records. Figure 2 illustrates important investigative tools used in this process.

Neurological examination usually reveals no focal signs. The Glasgow Coma Scale is a standard way of recording level of consciousness (p. 129). Focal signs, especially in the elderly, raise the possibility of a chronic subdural haematoma. There may be signs in keeping with pre-existing neurological disease such as Parkinson’s disease. Fidgeting and picking at objects that are not there is common in delirium, especially relating to alcohol withdrawal. Very occasionally a confused patient will have stereotyped movements of a limb or the face, which are a manifestation of recurrent complex partial seizures or non-convulsive status epilepticus (continuous absence or complex partial seizures). These can be very subtle and an EEG is required for diagnosis.

Bed-side higher function testing (pp. 12–13) documents the pattern of disturbance. Disorientation is particularly prominent with marked abnormal measures of attention, for example digit span. Usually the most useful documentation is specific observation regarding behaviour. Simple scales such as the Mini-Mental State score can be useful if somewhat crude.

Investigations

metabolic screen – glucose, sodium, urea, calcium, liver function tests, gamma-glutamyl transferase, drug screen, blood gases, red cell transketolase

metabolic screen – glucose, sodium, urea, calcium, liver function tests, gamma-glutamyl transferase, drug screen, blood gases, red cell transketolase