Chapter 587 Conditions That Mimic Seizures

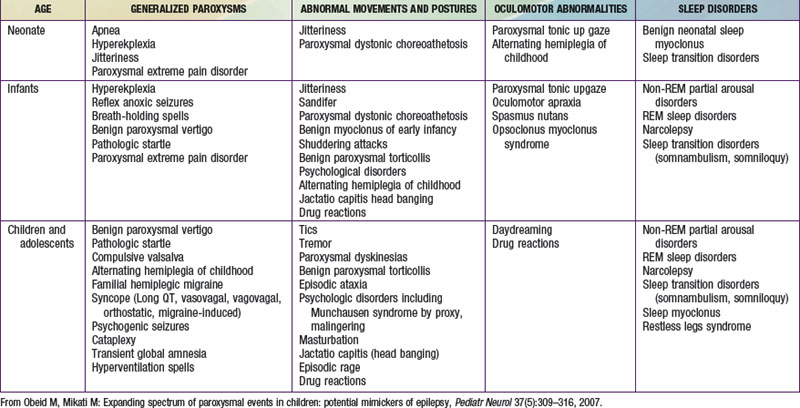

The misdiagnosis of epilepsy has been estimated to be as high as 5-40%, implying that many patients may be subjected to unnecessary therapy and tests. Often all that is needed to differentiate nonepileptic paroxysmal disorders from epilepsy is a careful history and thorough exam; but sometimes, more advanced testing may be necessary. Nonepileptic paroxysmal disorders can be classified according to the age of presentation and the clinical manifestations: (1) generalized paroxysms, (2) abnormal movements and postures, (3) oculomotor abnormalities, and (4) sleep-related disorders (see Table 587-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Generalized Paroxysms

Familial Hemiplegic Migraine

This is a rare type of migraine with a motor aura of weakness. Attacks begin as early as 5-7 yr of age. In a genetically susceptible person, attacks may be precipitated by head trauma, exertion, or emotional stress. Interictal cerebellar deficits (e.g., nystagmus, ataxia) may be present. Familial and sporadic cases are equally prevalent. The 3 genes implicated in the familial types are SCN1A (neuronal sodium channel subunit), CACNA1A (neuronal calcium channel subunit), and ATP1A2 (sodium potassium ATPase subunit). Several types of familial hemiplegic migraines can have coexisting seizures (e.g., in association with mitochondrial encephalopathy with lactic acidosis and strokelike episodes [MELAS], occipital epilepsy, and with episodic ataxia [Chapter 586.2]).

Psychologic Disorders

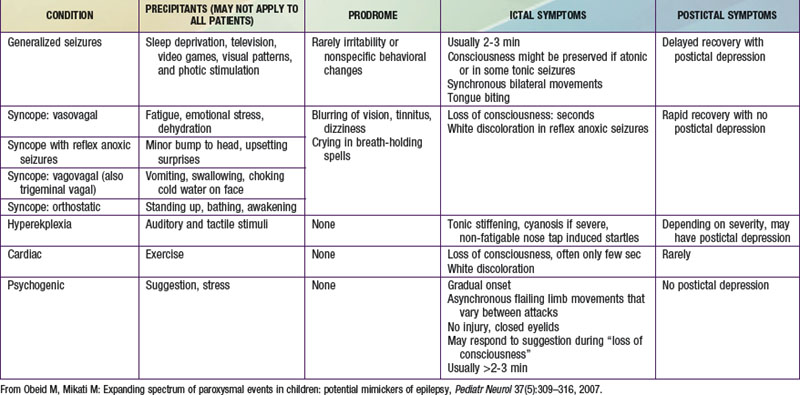

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures are conversion reactions that are usually suspected clinically based on the characteristics of the spells (Table 587-2). The diagnosis can be confirmed by video EEG with capture of an episode to eliminate any residual doubts about their nature, as they can often occur in patients who also have epileptic seizures. Psychogenic seizures are also less likely than epileptic seizures to be associated with increased serum prolactin levels 15-120 min after the event. They are best managed acutely by reassurance about their relatively benign nature and by a supportive attitude. Psychiatric evaluation and follow-up are needed to uncover potential underlying psychopathology, particularly in adolescents and adults, and to establish continued support as psychogenic seizures can persist over long periods of time. Malingering and Munchausen syndrome by proxy are often difficult to diagnose but an approach similar to that for psychogenic seizures, including video-EEG monitoring, is often helpful.

Abnormal Movements and Postures

Paroxysmal Dyskinesias and Other Movement Disorders

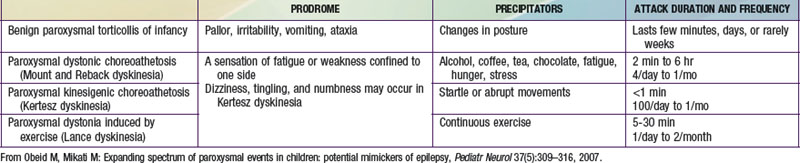

These disorders are characterized by sudden attacks that consist of choreic, dystonic, ballistic, or mixed movements (Table 587-3). A sensation of fatigue or weakness confined to 1 side may herald an attack. Consciousness is preserved and patients may be able perform a motor activity, like walking, despite the attack. The variability in the pattern of severity and localization between different attacks may also help in differentiating them from seizures. The frequency of attacks increases in adolescence, and steadily decreases in the third decade. Neurologic exam between attacks, EEG, laboratory investigations, and imaging studies are normal. These dyskinesias often respond to phenytoin, carbamazepine, clonazepam, or to antidopaminergic drugs such as haloperidol. Drug reactions can result in abnormal movements such as oculogyric crisis with many antiemetics, choreoathetosis with phenytoin, dystonia and facial dyskinesias with antidopaminergic drugs, and tics with carbamazepine. Strokes, focal brain lesions, connective tissue disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus), vasculitis, or metabolic and genetic disorders can also cause movement disorders. Mutations of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1/SLC2AI) gene have been described in patients with exercise-induced dyskinesia.

Oculomotor Abnormalities

Sleep Disorders

Bakker MJ, van Dijk JG, van den Maagdenberg AM, et al. Startle syndromes. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:513-524.

Crompton DE, Berkovic SF. The borderland of epilepsy: clinical and molecular features of phenomena that mimic epileptic seizures. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):370-381.

Dauvilliers Y, Arnulf I, Mignot E. Narcolepsy with cataplexy. Lancet. 2007;369:499-511.

DiMario FJJr. Paroxysmal nonepileptic events of childhood. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2006;13:208-221.

Fertleman CR, Ferrie CD, Aicardi J, et al. Paroxysmal extreme pain disorder (previously familial rectal pain syndrome). Neurology. 2007;69:586-595.

Tan KM, Lennon VA, Klein CJ, et al. Clinical spectrum of voltage-gated potassium channel autoimmunity. Neurology. 2008;70:1883-1890.

Webster G, Berul CI. Congenital long-QT syndromes: a clinical and genetic update from infancy through adulthood. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:216-224.