CHAPTER 7 Conditions of the Reproductive Organs

UTERINE FIBROIDS

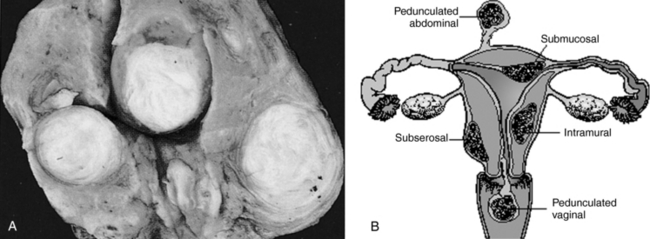

Uterine fibroids (properly called leiomyomata or myomas) are solid, well-defined benign monoclonal tumors of the smooth muscle cells of the uterus (Fig. 7-1).1,2 They range in size from microscopic to many pounds in weight, and may be singular or clustered. Multiple myomas in the same uterus are not clonally related.3 Fibroid size is described in comparison to a pregnant uterus (i.e., a fibroid the size of a 16-week pregnancy). As many as 20% to 40% of all women develop fibroids by age 40.1 Approximately 17% of all hysterectomies performed in the United States are for uterine myomas, with a peak incidence of surgery occurring for women around age 45, making fibroids the primary annual cause of premenopausal hysterectomy in the United States.3,4 They are rare in a premenarchal young women and shrinkage typically occurs in post-menopausal women with the natural decline in estrogen levels, unless stimulated by exogenous estrogen (foreign estrogens usually a result of environmental exposure, for example, from pesticides or plastics).1 For unknown reasons, fibroids are two to three times more common in black women than white, Asian, and Hispanic women.1,3 Fibroids are classified according to their site of growth in the uterine or surrounding tissue as submucosal, intramural, and subserous (see Figure 7-1). They also may occur in the cervix (cervical fibroids), between the uterine broad ligaments (interligamentous fibroids), or they may be attached to a stalk (pedunculated fibroids) and protrude into the uterine cavity (pedunculated submucosal fibroids) or through the cervix.1,3

Figure 7-1 Uterine fibroids.

Salvo S: Mosby’s Pathology for Massage Therapists, St. Louis, 2004, Mosby.

The exact etiology of uterine fibroids remains undetermined.5 Leiomyomas are hormone dependent. This is evidenced by the fact that they develop during hormonally active years and decline during menopause, fibroid tissue has an increased number of estrogen and progesterone receptors, fibroid tissue is hyperestrogenic, hypersensitive to estrogen, and does not possess the normal regulatory mechanism that limits estrogen response, the peak mitotic activity occurs during the luteal phase, and they respond to treatment with gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists.3, 6 7 8 Growth factor also plays a role in leiomyomata development.3,9 As estrogen and progesterone levels rise, insulin is released causing the transient hypoglycemia commonly experienced premenstrually. When plasma glucose levels fall, pituitary growth hormone is released, exerting bodywide effects. Its action on hepatocytes causes the release of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs). In a study by Vollenhoven et al., it is postulated that the net effect of these changes increases the bioavailability of free (bioactive) IGF, which may play a major role in promoting fibroid growth.9 A further study by De Leo and Morgante states that concentrations of epidermal growth factor, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF 1), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF AB) are present in myomatous tissues together with their receptors.6 Prolactin also may be a factor. Leiomyomata express a number of hormones, including parathyroid hormone–related protein (a growth factor), prolactin, and IGF.3

Factors that might increase fibroid development and growth include:

The use of oral contraceptives is not associated with any changes in fibroid size, and may even be protective; however, one study reported a slight increase in risk with a history of OC use beginning in the early teenage years. 2 3 4

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Myoma risk is inversely related to increasing parity and age at last pregnancy, and is decreased by smoking (due to its inhibition of estrogen) and increased by obesity (likely due to increased estrogen levels) and hypertension. 1 2 3,10 Fibroids occur in 1% to 2% of pregnancies. However, it is uncertain whether this relationship is entirely causal. Infertility, as well as early pregnancy loss, may be due to mechanical obstruction of implantation or distortion of the cervix or endometrium. Once a pregnancy is established, it is rare for myomata to interfere with its progress, and most proceed uncomplicated. However, a higher rate of cesarean section has been noted, and premature labor may result from very large myomata.1 Degeneration of fibroids, caused by hemorrhagic infarction, may rarely occur during late pregnancy and is marked by pain, and also may be accompanied by rebound tenderness, fever, nausea, vomiting, and leukocytosis.3 Treatment consists of rest and analgesia; surgery is a last resort.

Anemia and fatigue can be caused by excessive blood loss associated with fibroids. Pressure on the bowel or bladder can cause constipation, urinary frequency, and dyspareunia. Large fibroids may mask the diagnosis of serious gynecologic neoplasm. Rapidly growing fibroids may indicate a more serious pathology such as leiosarcoma and should be investigated. Malignancy is rarely associated with uterine fibroids; however, they occur with increased frequency in endometrial hyperplasia and are associated with a fourfold increased risk of developing endometrial cancer.1

SYMPTOMS

Most women with myomas are asymptomatic, never knowing that they have them unless informed of such by gynecologic examination. This was actually discovered based on ultrasound and autopsy results revealing that many more women had fibroids than had ever been diagnosed or treated for symptoms.2 The most common symptoms are menorrhagia and the physical effects caused by large myomata such as increased pelvic pressure, frequent urination, difficulty with defecation, and dyspareunia with deep penetration.1,3,5 Abnormal uterine bleeding is present in about 30% of all patients, and periods are typically heavy and prolonged, often with premenstrual and postmenstrual spotting.2,4 Uterine bleeding caused by myomas can be associated with significant social, emotional, financial, and medical difficulties; women’s concerns should be addressed. Some women experience dysmenorrhea.2 Metrorrhagia, may occur, but should be evaluated with an endometrial biopsy to rule out other endometrial disease.4 About 2% to 10% of women experience infertility as a result of fibroids, ostensibly due to abnormal uterine of tubal motility, interference with sperm movements, or abnormal uterine blood flow.3,11 Fibroid degeneration, torsion, or compression of a nerve against the pelvis caused by encroachment by a fibroid can lead to significant pain.4,11

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis can be determined by:

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Unless fibroids are symptomatic, observation is the most prudent form of treatment and no other intervention is necessary.1,4 GnRH agonists (e.g., Leuprolide) have been used effectively to control symptoms and reduce myoma size through suppression of estrogen and progesterone production.3,12 Mean uterine size decreases 30% to 64% after 3 to 6 months of treatment, and symptoms associated with fibroids are alleviated as a result. Possible side effects include hot flashes, headache, vaginal dryness and vaginitis, decreased libido, joint and muscle stiffness, and depression, and 30% of patients continue to have light, irregular vaginal bleeding.3,12 Local allergic reaction occurs in about 10% of patients.3 Bone loss occurs but is reversible, and a small number of women (2%) experience major vaginal hemorrhage 5 to 10 weeks after treatment commences. Steroid add-back therapy has been investigated to prevent bone loss in women requiring long-term GnRH therapy; however, because of the risk of osteoporosis, long-term therapy is inadvisable.3,12

Surgery should be reserved for women who are past childbearing, who are heavily symptomatic and not responsive to drug therapy, or who have suspected malignancies. Women wanting to preserve childbearing ability should be given the option of conservative therapy. GnRH therapy may be prescribed as pretreatment for surgical procedures to reduce fibroid size and bleeding. Myomectomy may be performed vaginally, hysteroscopically, or laparoscopically, and when performed skillfully, improves symptoms in 80% to 90% of patients. Between 15% and 30% experience fibroid regrowth after 5 years. Uterine scarring may occur from the procedure and affect fertility.12 Endometrial ablation and uterine artery embolization (UAE) are additional options.13,14 UAE is increasingly popular, and appears generally safe, but it is uncertain how long the treatment lasts and whether future fertility may be affected. The procedure involves injection of polyvinyl or gelatin particles into the uterine arteries to cut off blood supply to the fibroids, which leads to shrinkage over the next 3 to 12 months. Approximately 85% of patients gain relief from the procedure, which has been performed since 1995. However, it is not risk free. Adverse outcomes include infection, bleeding, and formation of emboli, as well as future fertility problems. For women intending to become pregnant in the future, myomectomy may still be the most certain conventional surgical intervention.14 Hysterectomy is generally recommended when women are past childbearing age, are symptomatic, malignancy is suspected, or if other therapies are ineffective.1,3,12

BOTANICAL TREATMENT

Among Western herbalists specializing in gynecologic complaints, there is a common perception that although symptoms of uterine fibroids are not difficult to control with botanical medicines, and their growth can be arrested, they are difficult to eliminate entirely unless the fibroid is small at the onset of treatment (smaller than 12-week size). Many women are content to have symptom control over pharmaceutical or surgical intervention, as long as the fibroids present no mechanical problems.15 Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has clearly defined diagnostic constructs, many herbal formulae, and well-developed adjunctive treatment protocols (e.g., acupuncture, moxibustion) for treating uterine fibroids and has claimed success in entirely eliminating uterine fibroids.

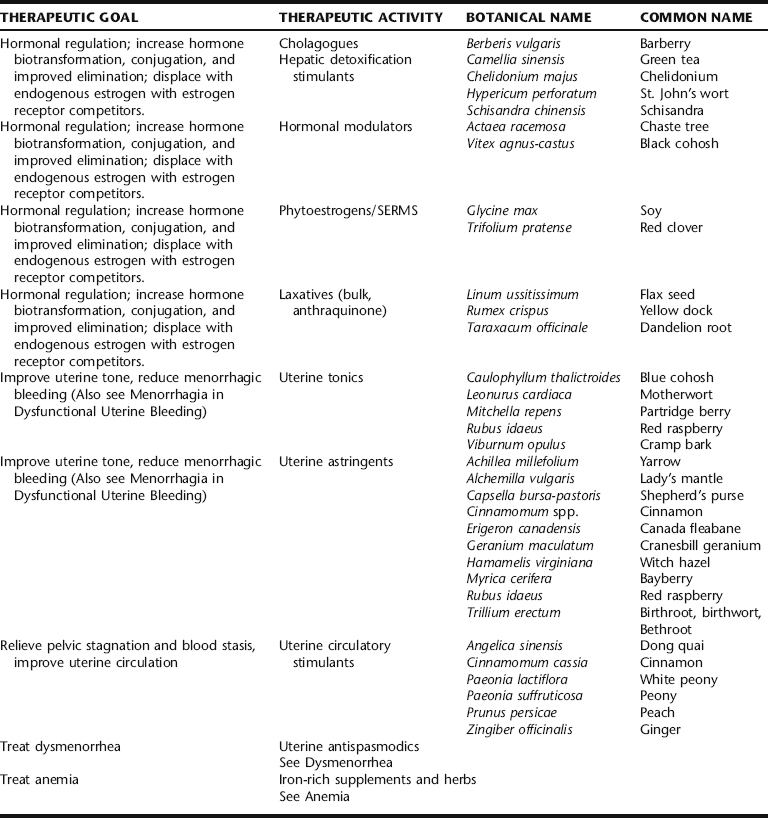

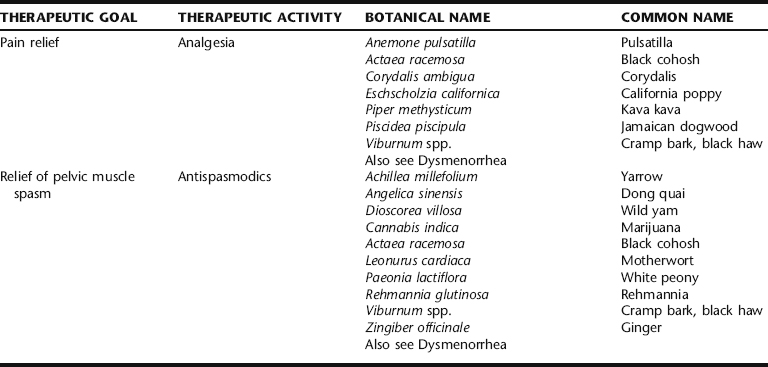

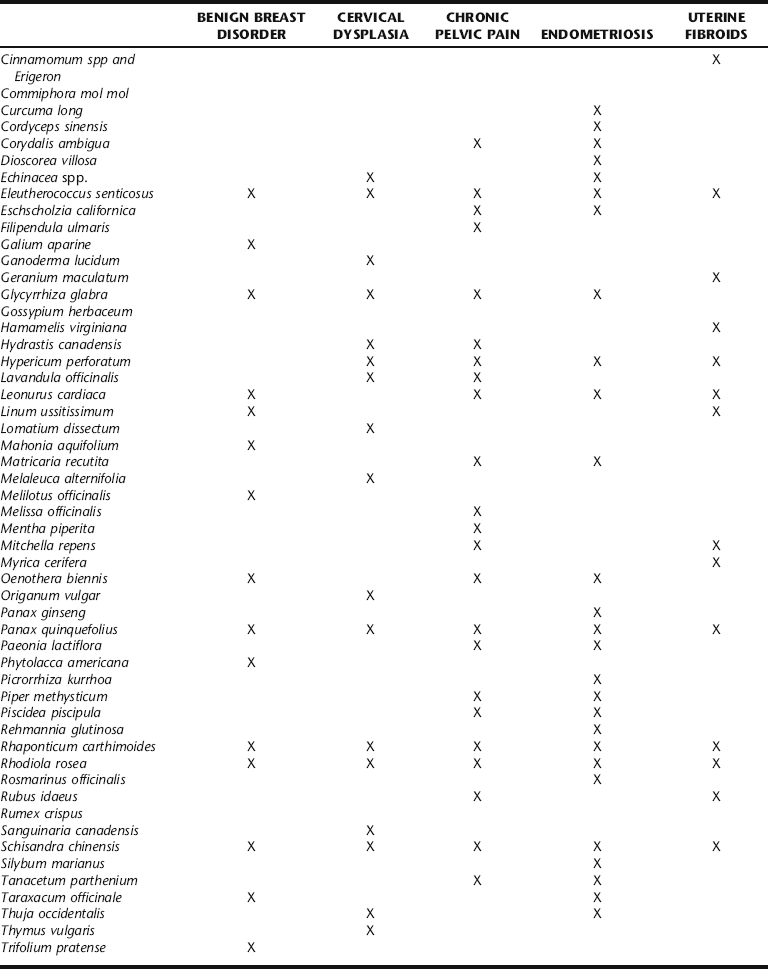

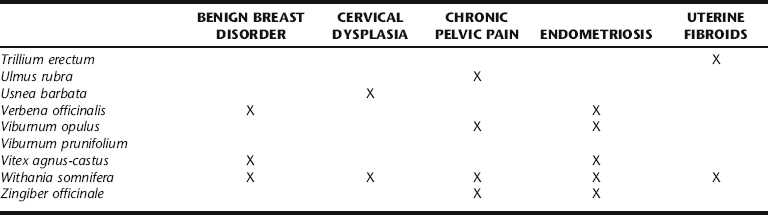

Western herbal treatment protocols include a variety of strategies (Table 7-1). These include weight reduction, promoting hormonal balance, specifically through the elimination of estrogens by enhancing liver detoxification mechanisms, promoting pelvic circulation while simultaneously controlling bleeding if necessary, and general improvement of uterine tone. These are integrated with the general recommendation to avoid excess exposure to xenoestrogens (environmental estrogens) and reduce overall estrogen levels, exposure to both being a risk factor for the development of uterine fibroids. Women with fibroids report greater frequency of red meat and pork intake, and less frequent green vegetable, fruit, and fish consumption.4 Although there is little correlation between the development of uterine fibroids and cancer, numerous studies have demonstrated a connection between diet, estrogen levels, and hormone-dependent cancers, as well as a protective effect of fruit and vegetables against cancer.4 No studies have evaluated the effects of US dairy consumption and the development of uterine fibroids. However, an association between dairy intake and increased risk of ovarian cancer has been reported.16,17 Herbalists recommend that patients avoid foods that increase risk, and emphasize intake of those shown to facilitate estrogen biotransformation, for example, by increasing dietary fiber, and regular intake of complex carbohydrates as found in vegetables and grains.11,18,19 Botanical strategies are aimed at reducing the estrogen burden through liver detoxification and improved elimination, promoting gynecologic health in general by improving pelvic circulation, reducing symptoms, and controlling fibroid size.

TCM treatment for fibroids has been evaluated through several preliminary studies, which are presented in the following section. Western botanical protocol for the treatment of uterine fibroids has not been subjected to controlled trials.4 The Western botanical information presented in this chapter reflects the opinions of herbalists practicing in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, regarding the efficacy and safety of the primary herbs used to treat myomas. Given the general safety of the botanicals being discussed, and the lack of noninvasive long-term effective medical treatments for fibroids, it seems that investigation of the primary Western herbal protocols cited in Table 7-1 is warranted. Nervines, laxatives, adaptogens, and other herbs included in fibroid protocol are discussed elsewhere throughout this text. Stress reduction should not be overlooked as part of the treatment protocol for women with symptomatic fibroids, as chronic uterine bleeding can cause emotional, social, financial, and medical consequences.2

Traditional Chinese Medicine Treatment

Cinnamon and Peony

Traditional Chinese medicine has numerous well-developed treatment protocols and formulations, some of which have been used for several centuries for promoting gynecologic health in general and for treating uterine fibroids specifically. For a more comprehensive review of the Chinese treatments for gynecologic problems, readers are referred to the primary TCM literature. Generally speaking, TCM views uterine myomas as a result of poor circulation of chi (energy) and blood through the pelvic region. Many formulas are designed to dispel pelvic stagnation and increase the flow of blood to uterine and ovarian tissues and facilitate the smooth flow of blood via menses. A classic TCM formula used for relieving blood stagnation is Cinnamon Twig and Poria Pill (gui zhi fu ling wan) consisting of: Cinnamomum aromaticum twigs, Poria cocos, Paeonia lactiflora root, Paeonia suffruticosa root, and Prunus persica seed. It should also be noted that in TCM, each herbal formula has specific diagnostic criteria for which it is used as well as clear contraindications and cautions. For maximum efficacy in using TCM protocols, a qualified herbal TCM practitioner should be consulted. In addition to herbal protocol for promoting gynecologic health and specifically treating uterine fibroids, TCM also employs numerous other modalities, which may include walking to promote circulation in general and abdominal circulation specifically, moxibustion, acupuncture, external application of compresses, and other such adjunctive therapies. Specific lifestyle recommendations also can be given such as the avoidance of cold foods and drink (in TCM coldness is said to cause congealment and stagnation) and constrictive clothing.20

Several studies have looked at the efficacy of the Cinnamon Twig and Poria Pill formula noted in the preceding section for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Specifically, the studies investigated the effectiveness of the Japanese version of this formula (Keishi-bukuryo-gan, KBG) in an open study on 110 premenopausal women with symptomatic uterine fibroids measuring less than 10 cm in diameter. They were treated with 22.5 g/day of a freeze-dried decoction of the herbs for 12 weeks. Twenty-one women were considered “normal” and 47 women much improved by the end of the trial. This herbal formula is frequently used to treat a range of gynecologic disorders including dysmenorrhea, cervical erosion, ovarian cysts, chronic salpingitis, and endometriosis, to name a few conditions.15 There is research to suggest that the Paeonia species in this formula may act as an LH-releasing hormone (LH-RH) antagonist with weakly antiestrogenic effects in the presence of estrogen.21 In another study, the authors applied individualized TCM formulations and treatments to treat 223 cases of uterine fibroids with a reported 72% reduction of menorrhagia in 160 women complaining of this symptom, 58% improvement in backache, and an overall effectiveness rate of 92.4%. Myomas were eliminated in 29 of 223 patients and markedly diminished in 42 patients. In 32 patients, no changes were seen and there were no positive results in 12.5% of patients.15 If the TCM treatments were tailored to the individual patients, then this can be kept with the addition I made. If the treatment was specific, a similar level of detail as the previously reported study should be given for consistency of presentation.

In an interesting study by Mehl-Madrona et al., an integrated TCM-Western medicine pilot study was conducted to compare the cost and efficacy of a set of therapies typically used by CAM practitioners and conventional medicine on ability to reduce uterine fibroid size. All patients were premenopausal and age 24 to 45 years, educated, employed, and from a socioeconomic bracket that allowed them to pay cash for all treatments. None were on pharmaceutical treatment or hormonal contraceptives at the time of the study and all received a pelvic ultrasound before and again 6 months after treatment. Sonograms were obtained on patients who dropped out of the study as well, so sonograms were available on all patients. Uterine fibroids measured at least 6- to 8-week pregnancy size, with palpable fibroids 2 to 3 cm in diameter. Inclusion in the study required hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL, with fibroid growth of less than 6 cm/year. CAM treatment included a combination of nutritional, herbal, acupuncture, bodywork, and psychological interventions. Acupuncture and herbal protocols were selected individually for the patient, using formulae and points traditionally indicated for the patient’s patterns: symptoms, constitution (based on TCM pulse and tongue diagnosis), and condition. The comparison group used progestational agents, oral contraceptives, and NSAIDs. The results of this study demonstrated no statistically significant difference in change of symptoms between the two groups when measured after 6 months of treatment. Both experienced improvement in symptoms and fibroid size. Patients in the treatment group considered the pilot study a success because they were able to achieve results equivalent to pharmaceutical interventions using nonconventional methods.15

Hormonal Modulators

Chaste Berry

Chaste berry is the primary herb employed by herbalists and integrative medicine practitioners for hormonal modulation in the botanical treatment of fibroids.4,22 It acts as a dopamine agonist, resulting in a reduction in prolactin release.23 Prolactin may play a role in fibroid growth. No scientific evidence in the literature has been found for the use of chaste berry specifically in the treatment of fibroids, and although its use may result in reduction of apparent estrogen excess due to relative progesterone deficiency, increased progesterone levels have been shown to result in increased mitotic division in fibroid tissue. Wuttke et al. studied the putative estrogenic effects of a chaste berry extract and found it contained substances that replaced radiolabeled estradiol from a cytosolic estrogen receptor preparation, and appeared to be agonistic to ERβ. However, because the uterus expresses ERα, no effects on the uterine expression of estrogen were expected or have been experimentally observed.23

Phytoestrogens and Selective Estrogen Receptor Modules

Phytoestrogens are plant compounds with a similar molecular shape and structure to endogenous estrogen molecules, and which can bind competitively to estrogen receptors, preventing the binding of more potent estrogen and estrogen metabolites (see Part IV).24 They appear to behave similarly to selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs). Low Dog explains their potential clinical application in conditions of estrogen excess, in relationship to the role of phytoestrogens in breast cancer treatment:

By binding to estrogen receptors in the premenopausal woman, phytoestrogens “turn down” estrogen production through negative feedback at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland…when endogenous estrogen levels are high, phytoestrogens may have an antiestrogenic activity by preventing estrogen from binding to the estrogen receptor through competitive inhibition.25

Legumes, including soybeans and red clover, are rich in phytoestrogens.26 In a study by Liu et al. methanol extracts of red clover (Trifolium pratense), chaste berry, and hops (Humulus lupulus) showed significant competitive binging to both ERα and ERβ. In the same study, dong quai (Angelica sinensis) and licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis) showed weak ER binding, whereas black cohosh did not exhibit any competitive binding. Controversy abounds as to the mechanisms of action of black cohosh, which do not appear to be directly phytoestrogenic.27 Current research is suggesting a dopaminergic or serotonergic effect for this botanical.25,27 The application of phytoestrogens may be a promising area for further investigation for the botanical treatment of fibroids, and should be considered in the development of botanical protocols.

Hormone Excretion and Biotransformation

Greater than 50% of all estrogen metabolism and conjugation occurs in the liver, suggesting a basis for the belief among herbalists that herbs that improve liver function may increase estrogen excretion and either treat or lower the risk for uterine fibroids.4,22 Herbalists commonly include liver-specific herbs in formulae for treating fibroids. Several herbs actively effect phase 1 and phase 2 liver detoxification systems and CYP450, an enzyme system partially involved in the metabolism of estrogen. These effects and their relationship to uterine fibroid treatment, if any, have not been formally investigated but are often applied by modern herbal practitioners in putatively reducing estrogen burdens. Cholagogues, herbs which stimulate the release of bile from the gallbladder, also may be useful for clearing estrogen through increased bowel clearance resulting from their indirect laxative action. Examples of cholagogues include bayberry and chelidonium.22

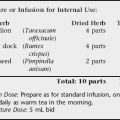

Uterine Tonics, Astringents, and Hemostatics

Because bleeding is a common symptom of uterine fibroids, numerous antihemorrhagic herbs are used in botanical medicine protocols (see Menorrhagia in Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding).22 Yarrow dried plant infusion is perhaps one of the most widely used uterine antihemorrhagics, reliably reducing acute uterine bleeding, but conversely promoting menstrual flow when suppressed. It has been used since ancient times as a styptic.25 Either dry or fresh plant can be used as a tea or tincture. Many herbalists believe that yarrow herb taken as tea is more quickly effective for stopping acute uterine bleeding than other preparations. Other traditionally used uterine antihemorrhagic herbs include lady’s mantle, shepherd’s purse (fresh only), cranesbill geranium, witch hazel, bayberry, red raspberry, and bethroot. These are all generally

| Yarrow | (Achillea millefolium) | 40 mL |

| Lady’s mantle | (Alchemilla vulgaris) | 20 mL |

| Bayberry bark | (Myrica cerifera) | 15 mL |

| Shepherd’s purse | (Capsella bursa-pastoris) | 15 mL |

| Cinnamon | (Cinnamomum cassia) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

taken in tincture form in 2- to 4-mL doses repeated every 15 minutes as needed until bleeding subsides, or combined into larger formulae for the treatment or prevention of chronic menorrhagia. Shepherd’s purse in particular has been used traditionally as a uterine antihemorrhagic. The 1986 Commission E monograph recommends daily oral doses of 10 to 15 g of crude herb (or equivalent in extract) for mild gynecologic bleeding.28 Extracts of the drug contain a hemostyptic action, likely owing to the presence of a peptide that has demonstrated oxytocin-like activity in vitro.28,29 Many modern Western herbalists believe that it is imperative to prepare Shepherd’s purse from fresh, not dry, plant material. Lady’s mantle’s mechanism of action lies in its high tannin content, indicating it for bleeding, diarrhea, and wound healing, a likely mechanism for many of the other herbs used as uterine antihemorrhagics.29 The combination of Cinnamomum and Erigeron was relied upon by the Eclectics for uterine hemorrhage, and is still employed by midwives today for the treatment of nonemergency postpartum bleeding, and by herbalists for the treatment of menorrhagia.30,31 Red raspberry leaf is typically used more as a long-term uterine tonic than to arrest acute bleeding. Blue cohosh has been used historically for its utero-tonic actions. It is listed in the 1918 US Dispensatory for the treatment of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea, and is still widely used by herbalists for these conditions.32

Relieving Uterine Stasis: Circulatory Stimulants

Improving pelvic circulation and relieving stasis is a common approach to fibroid treatment in both Western and traditional Chinese herbal medicine, based on the belief that relieving stagnation and congestion in the pelvis will facilitate the removal of “blockages” and growths (e.g., fibroid tissues), remove wastes, and promote greater health and nourishment of the pelvic organs in general.11,18,20 Decreasing pelvic stagnation is also thought to help reduce uterine hemorrhage. Ginger and cinnamon are both traditionally used to increase circulation to the reproductive organs. Further, cinnamon has been used historically to reduce uterine bleeding, making it specific for the treatment of uterine fibroids with menorrhagia or metrorrhagia.30,31 White peony, an ingredient in Keishi-bukuryo-gan, discussed in the preceding, is a common herb used in TCM for the treatment of women’s disorders, including menstrual dysfunction and uterine bleeding.33 Red peony is often combined with white peony and peach seed to dispel blood stasis, and conditions associated with it, including excessive uterine bleeding, particularly with the presence of thick, purple clots.33

Treatment Protocol

| Lady’s mantle | (Alchemilla vulgaris) | 25 mL |

| Raspberry | (Rubus idaeus) | 30 mL |

| Nettles | (Urtica dioica) | 20 mL |

| White peony | (Paeonia lactiflora) | 15 mL |

| Ginger | (Zingiber officinalis) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

After 3 months the above protocol was modified to:

| Red raspberry leaf | (Rubus idaeus) | 40 mL |

| White peony | (Paeonia lactiflora) | 40 mL |

| False unicorn | (Chamaelirium luteum) | 15 mL |

| Ginger | (Zingiber officinalis) | 5 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

| Ashwagandha | (Withania somnifera) | 40 mL |

| Lemon Balm | (Melissa officinalis) | 30 mL |

| Hops | (Humulus lupulus) | 15 mL |

| Valerian | (Valeriana officinalis) | 15 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Xenoestrogens/Endocrine Disruptors

Avoid xenoestrogen ingestion from pesticide and herbicide residue by eating organically cultivated foods and avoiding foods in plastic containers. Xenoestrogens are found most concentrated in the fat of meat, farmed fish, and nonorganic dairy products.12 Eating primarily organic meat, dairy, and produce, washing fruits and vegetables thoroughly before eating, and minimizing the use of soft plastics, such as for food storage, can help reduce xenoestrogen intake.

Estrogen Biotransformation and Diet

Metabolism and detoxification of estrogen in the body ultimately determines its biological effects. Estrogen biotransformation occurs mainly in the liver through phase I hydroxylation and phase II methylation and glucuronidation, allowing estrogen to become a water-soluble, excretable compound.11 This is predominantly excreted by the liver in bile (see Dietary Fiber). Phase I detoxification yields three estrogen metabolites with highly variable biological activity: 2-hydroxyestrone (2-HE), 16-alpha-hydroxyestrone (16α-HE), and 4-hydroxyestrone (4-HE). 2-HE is a beneficial estrogen metabolite in that among its effects, it competitively binds estrogen sites, blocking more potent estrogens. Conversely, 4-HE and 16α-HE are potent estrogens that may promote the growth of estrogen-sensitive tissue.11 Dietary consumption of cruciferous vegetables, such as broccoli and cabbage, as well as green tea, garlic, and rosemary can increase the amount of 2-HE by modifying P450 activity in phase I, and have antioxidant effects as well.11,34

Dietary Fiber

Once estrogen metabolites are excreted by the liver in bile, the metabolites are soaked up by fiber in the small intestines and excreted via defecation. If the diet lacks fiber, bile, along with the estrogen metabolites are reabsorbed, adding an unnecessary estrogen burden to the body. Soluble fiber such as the lignins found in flax seeds also increases sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), decreasing the amount of available active estrogen, as estrogen bound to SHBG is rendered inactive.11 Brassicae vegetables such as cabbage and broccoli contain indole glucosinolates, which when chewed, are degraded by a plant enzyme into a variety of indole structures. When degraded in the body, these structures induce cytochrome P450 expression (CY1A1) in hepatic and extrahepatic tissue, leading to greater conversion of 2-hydroxyestrone (2-HE), and decreasing the availability of E1 for conversion to 16-HE, thereby reducing the estrogen burden overall.25 This is partly associated with the anticancer effects associated with these foods.

ADDITIONAL THERAPIES

Treatment Summary: Uterine Fibroids

What to expect with treatment

Eclectic Specific Condition Review: Uterine Fibroids—a Historical Perspective

stress. Herbalists often recommend specific yoga postures or Kegel exercises to assist in improving pelvic circulation particularly.35 Vigorous walking, hip circling, pelvic thrusts, and belly dancing can all be useful to improve pelvic circulation.

FIBROCYSTIC BREASTS AND BREAST PAIN

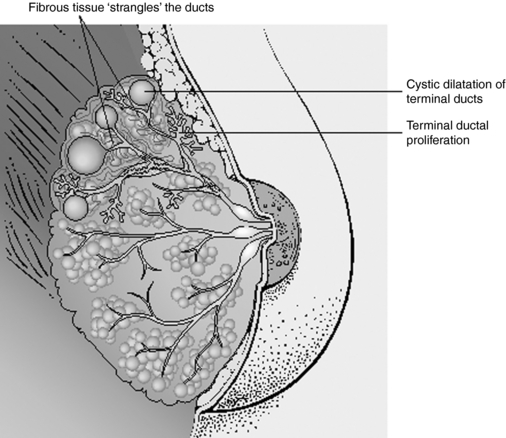

Benign breast conditions are a common finding in clinical practice, with fibrocystic breast changes and fibroadenomas occurring in 60% to 90% of all women.36 The hallmark of fibrocystic breast changes is that the cysts fluctuate in size and shape, may entirely disappear and reappear cyclically, and are associated with hormonal changes in the menstrual cycle. Women with this condition describe their breasts as feeling lumpy, “ropey,” and tender. The changes occur bilaterally. Fibroadenomas are mobile, solid, firm, rubbery masses that typically occur singly, and are not usually painful (Fig. 7-2). They are second only to fibrocystic changes as the most common of the benign breast conditions, and are commonly found in women in their 20s. Breast tenderness that accompanies the menstrual cycle is known as cystic mastalgia.38,39 Cyclic mastalgia may be associated with other premenstrual complaints. The terms benign breast disorder and benign breast disease are unfortunate misnomers, as they are neither a disorder nor disease. In only a small percentage of cases are the atypical ductal and lobular hyperplasias associated with increased risk of breast carcinoma. Practitioners consulting with women for fibrocystic breast changes and other findings must be sensitive to a patient’s increased anxiety about finding a breast lump, and provide clear information and calming reassurance both during the exam and while the patient awaits tests results if any were deemed necessary.

Figure 7-2 Comparison of normal and fibrocystic breast tissue.

Salvo S: Mosby’s Pathology for Massage Therapists, St. Louis, 2004, Mosby.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Fibrocystic breast changes are an exaggerated response to cyclic ovarian hormones.39 The etiology of fibroadenomas and cyclic mastalgia may also be hormonal, though in some cases, the cause of a fibroadenoma may be unclear. When this occurs in women over 30, removal of the mass is generally recommended.

DIAGNOSIS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are two primary aims when arriving at a diagnosis of fibrocystic breasts. The first is to rule out breast cancer, and the second is to determine if benign breast symptoms warrant treatment. A careful history, physical exam, and cancer risk assessment are indicated (Box 7-1 and Table 7-2).36 A thorough breast exam is best performed after the menses, as examination prior to menses (when the pain is actually likely to be most acute) can obscure problematic lumps caused by normal breast tissue proliferation and nodularity from normal hormonal changes. If a suspicion of breast cancer remains after the history and physical, further diagnostic tests should be performed as appropriate.36 Diagnosis of fibrocystic breasts can be made on the basis of cancer exclusion. For women experiencing symptoms including pain, tenderness, swelling, inflammation, or nipple discharge, the comprehensive history and physical can be used to determine if the problem is cyclic or noncyclic in nature and whether it is associated with other signs and symptoms, including fever or premenstrual mood swings. It is also important to gently move aside the breast tissue and examine the chest wall and muscle to determine whether breast pain or muscle pain is the proper diagnosis.40 Depending on the associated signs and symptoms, a diagnosis, including breast infection, muscle sprain/strain, premenstrual syndrome, or noncyclic mastalgia can be determined.

TABLE 7-2 Risk for Development of Breast Cancer by Type of Benign Breast Disease

| HISTOLOGIC PATTERN | APPROXIMATE RELATIVE RISK OF DEVELOPING BREAST CARCINOMA | PROPORTION OF BENIGN LESIONS* |

|---|---|---|

| Nonproliferative changes | No increased risk | 70% |

| Proliferative disease without atypical hyperplasia | Twofold increased risk | 27% |

** Family history limited to mother, daughter, or sister with breast cancer

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Conventional treatment for fibrocystic breasts includes encouraging women to wear loose fitting brassieres, decreased caffeine consumption, and smoking cessation, and a pharmacologic focus on hormonal modulation, including oral contraceptives (OCs), prolactin antagonists, and antiestrogen agents as well as diuretics for moderate premenstrual mastalgia; and analgesics such as ibuprofen, salicylates, and acetaminophen for pain.36,38 Hormonal therapies often carry unwanted side effects, including weight gain, lipid profile changes, depression, and abnormal bleeding.36 Although OCs reduce symptoms in up to 90% of women, symptoms return upon discontinuation.36 Danazol, which suppresses the pituitary ovarian axis by inhibiting the output of both FSH and LH from the pituitary gland, is also used for mastalgia. Its side effects include virilization, muscle cramps, CPK elevations, and liver damage. Bromocriptine is also used for breast pain and nodularity but has several common side effects, including nausea, giddiness, and postural hypotension.36 Reduction in dietary fat intake has been shown to reduce cyclic mastalgia.

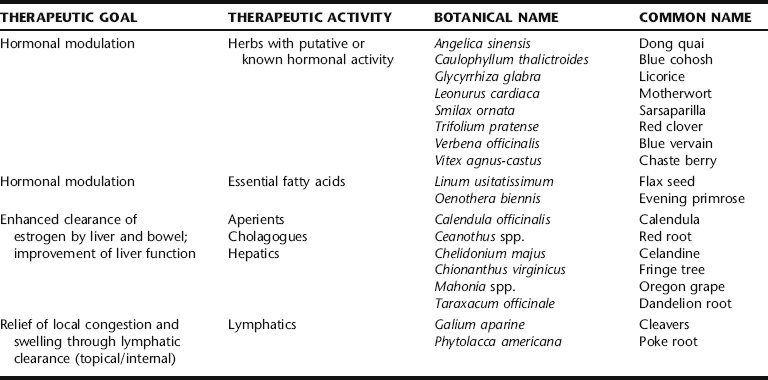

BOTANICAL TREATMENT

Botanical treatment for fibrocystic breasts has not been widely subject to scientific evaluation, in spite of this being a commonly treated condition in the herbal clinic. Treatment aims primarily at hormonal regulation through direct (i.e., HPA and HPO axes) and indirect (i.e., improved hormonal biotransformation and excretion) actions, and reduction of local congestion and symptomatic pain relief through topical applications (Table 7-3). The liver plays a central role in metabolizing and detoxifying sex hormones.34 Consequently, herbal practitioners typically include herbs that are known or thought to enhance hepatic detoxification functions in formulae for treatment of fibrocystic breasts.34 Such herbs, many of them considered “bitters,” include dandelion root, burdock, root, licorice root, Oregon grape root, fringe tree, motherwort, blue vervain, and celandine. These botanicals are usually included in ranges of 5% to 20% of formulae, in tincture or decoction forms. Although there has been little investigation of such herbs to establish their pharmacologic or physiologic action for such use, they are nonetheless a common part of the protocol for many gynecologic concerns, including benign breast complaints, and their role in formulae should be considered and further evaluated.

Chaste Berry

Chaste berry is extensively recommended by herbal practitioners for cyclic breast pain and fibrocystic breasts, both when it presents independently and when associated with PMS. This traditional use is supported by clinical trials. Chaste berry may be used singly or in combination with other herbs that enhance hormonal regulation and hormone metabolism (e.g., herbs that promote liver function and hormonal conjugation and elimination). There have been three placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized clinical trials (RCT) examining the effects and safety of a proprietary chaste berry extract–containing solution (VAC) on cyclic mastalgia. VAC is sold as Mastodynon®, and manufactured by Bionorica Arzneimittel GmbH (Neumark/Opf. Germany).41 It contains 32.4 mg of chaste berry fruit extract/60 drops as well as a mixture of homeopathic ingredients, including Caulophyllum thalictroides, Cyclamen, Ignatia, Iris, and Lilium. This product is available as both a tablet (MR 1025 E1) and a liquid extract in Germany. German drug indications for the product include menstrual disorders based on a temporary or permanent corpus luteum insufficiency, infertility resulting from corpus luteum insufficiency, and menstrually related complaints, including mastodynia.42 All three of the studies used the liquid solution, which contained 53% (v/v) alcohol, although the study by Wuttke et al. also used the tablets.41,43 All three studies defined cyclic mastalgia as having at least 5 days of breast pain the previous cycle and treated women for three menstrual cycles with 30 drops two times daily of VAC (1.8 mL/equivalent to 32.4 mg extract of chaste berry drug). Researchers found that both the severity (assessed on a 1- to 100-mm visual analog scale [VAS]) and presence of breast pain (as measured by women’s diaries) were significantly improved in the women who were assigned to the chaste berry groups compared with placebo after the first month of treatment. Although pain intensity was reduced by 30% in the chaste berry group compared with 11% in placebo after one cycle, pain intensity was even more reduced at the end of the second month of treatment, with 53% of women receiving chaste berry having decreased severity of breast pain compared with 25% of the placebo group (p = 0.006).41 No further improvement was obtained with longer treatment periods. However, to reduce the number of days with severe pain women needed to receive VECS for three to four cycles before they had significantly fewer days with breast pain compared with the placebo group (p = 0.21).41,44 Two of the studies also measured serum hormone levels including estradiol, progesterone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and basal prolactin levels at baseline and in the premenstrual weeks of cycles 1, 2, and 3.43,45 One study found a significant rise in prolactin levels and a decrease in progesterone levels,45 whereas another study found no effect on FSH, LH, and progesterone, but did see a decrease in estradiol levels and a significant decrease in basal prolactin levels (3.7 ng/mL tablets and 4.35 ng/mL liquid extracts) compared with placebo.43 Adverse events were rare and did not differ from placebo in any of the RCTs.

Dong Quai and Blue Cohosh

Along with chaste berry, dong quai and blue cohosh are commonly employed by herbal clinicians to modulate hormone levels. Blue cohosh, as part of the German herbal formulation Mastodyn® (reviewed in the preceding), may provide some of the therapeutic benefit of that formulation. However, to date, no studies have demonstrated that blue cohosh has any effect on hormonal levels. Dong quai in vitro can weakly bind to estrogenic receptors and induce progesterone receptors. However, it did not stimulate vaginal cells or increase endometrial thickness and had no estrogenic effect showing no transactivation of either alpha- or beta-estrogen receptors.27,46,47 Additionally, dong quai showed no significant effect on either hormonal levels or symptoms in an RCT in menopausal women.48,49 Consequently, dong quai appears to have a limited if any effect on hormone levels. In a recent study, dong quai was found to have significant anti-inflammatory effects because of one of its constituents, ferulic acid.50 Although this study is very preliminary, it may offer an alternative mechanism through which dong quai could be helping to decrease mastalgia in women with fibrocystic breasts. According to TCM theory, dong quai dissolves blockages and relieves blood stagnation, and is thus a common ingredient in formulae for mastalgia.

Flax Seed and Evening Primrose Oil

Flax seeds are the richest source of plant-based omega-3 fatty acids, with a-linolenic acid (ALA) being the primary fatty acid (18:3n-3).51 These fatty acids are considered strongly anti-inflammatory, being precursors for the anti-inflammatory series prostaglandins (PGE3). Flax seeds are also rich in fibers called lignins. Like isoflavones in soy and other foods, lignins and their associated phenolic compounds are classified as phytoestrogens.52,53 Flax seeds are an especially rich source of dietary lignins, with 75 to 800 times more than any other food source.51,54 Research has shown lignins to be a promising agent for binding excess sex hormones, including testosterone and estrogens. Through both its anti-inflammatory and possible anti-estrogenic effects researchers believed that flax may prove a beneficial treatment for fibrocystic breasts. One study examined the effect of eating one muffin daily supplemented with 25 g of ground flax seeds in 127 women with mastalgia.55 Women experienced a significant reduction of symptoms; however, the full results of this study were never published and thus it is unknown how long women needed to take the flax seed–enriched muffins, what symptoms were reduced, what the degree of symptom reduction was, or if there was any placebo control to assess for the considerable level of spontaneous remission (60% to 80%) of symptoms in women with breast pain over time.55 Evening primrose oil (EPO), is a rich source of omega-6 essential fatty acids (EFAs). EFAs are precursors to either series 1 or 2 prostaglandins, depending on substrate availability. The more omega-6 EFAs there are in the diet, the more likely it is for the inflammatory series prostaglandins to be made; conversely, the less omega 6 EFAs there are in the diet, the more likely it is for anti-inflammatory series 1 prostaglandins to be produced. Because of EPO’s potential anti-inflammatory properties, two randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials and one open-labeled trial of EPO in both cyclic and noncyclic mastalgia have been conducted. One double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study in 73 women with either cyclic or noncyclic mastalgia found that 1000 mg of EPO or placebo three times daily over 3 months significantly reduced symptoms of pain and tenderness in the women who received EPO compared with placebo.56 In a similar study, 291 women with severe persistent breast pain given either placebo or 1000 mg EPO three times daily for 3 to 6 months found that 45% of women with cyclic pain improved. Further, 27% of women with noncyclic breast pain improved compared with 9% in the placebo group.57 In a nonrandomized open-labeled study, 94 women with cyclic and 32 women with noncyclic mastalgia received 3 g of EPO for at least 4 months. Severity of pain was diminished in a “clinically useful”40 manner in 58%49 of the women with cyclic mastalgia and 38%12 of the women with noncyclic mastalgia taking EP. Unfortunately, all three of these studies are difficult to assess because of lack of reporting of how pain and symptoms were measured and how great the effect, and thus how clinically relevant the effect of EPO is in women with breast pain.40 The recommended dose of flax oil to treat and prevent mastalgia and nodularity is two to four 500-mg capsules twice daily or 1 to 2 tablespoons of the oil daily. One to three grams daily is the recommended dose of ground seeds.58 A typical dose of EPO is 1500 mg daily.

Red Clover

Red clover is rich in isoflavones, especially genistein and daidzein. Genistein and daidzein have weak estrogenic effects, which have led researchers to hypothesize that genistein may compete with stronger endogenous estrogens such as estradiol for estrogen receptors; although what effects this may have on breast tissue is unclear at this time. One unpublished study found that a red clover extract had a significant effect on improving mastalgia. No further information is available concerning this trial.59

Topical Applications

Poke Root

Poke root has traditionally been used to stimulate the immune system, relieve lymph congestion, and resolve

Botanical Protocol for the Treatment of Fibrocystic Breasts

I. Prepare the Following Tincture:

| Calendula | (Calendula officinalis) | 20 mL |

| Chaste berry | (Vitex agnus-castus) | 20 mL |

| Burdock root | (Arctium lappa) | 20 mL |

| Sarsaparilla | (Smilax ornata) | 20 mL |

| Dandelion root | (Taraxacum officinale) | 20 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

lumps and cysts, and by extension, has been widely applied topically for the treatment of fibrocystic breasts. Poke root oil is applied topically by rubbing in a small amount (1 tsp) of the oil throughout the affected breast(s) for at least 5 nights per week for 1 to 2 months. The addition of 5 to 7 drops each of rose geranium and sandalwood essential oils makes the oil slightly more stimulating to the local circulation and also adds a pleasant scent to the oil. All parts of the plant are toxic and can lead to contact dermatitis or even toxicity from handling large amounts. Internal use is not recommended without the supervision of a qualified practitioner.

CASE HISTORY: CYCLIC MASTALGIA

She was prescribed the following tea for her to take after supper to help her sleep:

| Passionflower | (Passiflora incarnata) | 2 parts |

| Chamomile | (Matricaria chamomilla) | 2 parts |

| Skullcap | (Scutellaria lateriflora) | 1 part |

For her mastalgia and menstrual irregularities, she was prescribed the following tincture:

| Chaste berry | (Vitex agnus-castus) | 20 mL |

| Burdock root | (Arctium lappa) | 20 mL |

| Cleavers | (Galium aparine) | 20 mL |

| Dong quai | (Angelica sinensis) | 40 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Elimination of Coffee, Tea, and Other Caffeinated Products

An association between caffeine, or methylxanthines, and fibrocystic breast disease has been reported but remains controversial. In one study of a group of 102 women who had mammograms performed to measure the level of fibrocystic breast disease, a strong correlation was found with both caffeine and total methylxanthine ingestion and fibrocystic breasts as determined by a series of questionnaires.60 Similar results were found in a large case control study of 634 women.61 Other studies, however, have found only weak associations. Normal fluctuations in hormonal effects on breast tissue and difficulty in consistently measuring caffeine or methylxanthine intake make it difficult to conclusively demonstrate a causal relationship.62,63 In a review of the literature presented on AltMedex, the following studies are cited: A controlled clinical trial showed no clinically or statistically significant effects of alcohol- or methylxanthine-free diets on signs and symptoms of fibrocystic breast disease. One hundred sixty-two women with clinical and thermographic diagnoses of fibrocystic breast disease completed the study with evaluation at 6 months. It was concluded that abstinence from alcohol or methylxanthine-containing beverages is not likely to substantially reduce severity of fibrocystic breast disease within a few months.64 A case control study examined the relationship between coffee consumption and the development of benign breast disease involving the analysis of 854 cases of histologically diagnosed benign breast disease and 1748 control subjects. No association between coffee consumption and benign breast disease was found; neither was a dose–response relationship between methylxanthine consumption and benign breast disease development noted. These results suggest no association between caffeine intake and the development of benign breast disease.65 In a randomized study, 158 women with breast concerns were divided into two groups; one group abstained from consumption of methylxanthine-containing foods and beverages. The second group (controls) had no dietary restrictions. The patients were re-examined at 4 months for palpable breast findings. One hundred forty patients completed the study. There was a statistically significant decrease in clinically palpable breast findings in the abstaining group compared with controls, but the absolute change was minor and may be of little clinical significance. This study offered little support for the claim that caffeine-free diets are associated with clinically significant improvement in benign breast disease.66 In a study of 66 patients, restriction of dietary caffeine ingestion can cause improvement in fibrocystic breast disease. Graphic stress telethermometry (GST) was performed as an objective monitor for fibrocystic breast. At baseline, an average score of 83.5 on GST was observed in these women. Following dietary methylxanthine restriction, these scores were observed to be an average of 69.5 at 2 months and 55.5 at 6 months. Forty-two of the 66 patients had decreases in GST scores of more than 20 points at 6 months. Eighty-five percent of the patients showed improvement in GST patterns at 6 months, 15% of patients showed no change, and none showed worsening in GST patterns. Subjectively, at 6 months, 22 of 66 patients reported marked improvement, 30 of 66 moderate improvement, 6 of 66 mild improvement, and 8 of 66 no change in symptoms of fibrocystic breast disease. At pretreatment, 78% of patients had 2+ or 3+ nodularity on palpation. At the 6-month examination, 89% of patients had no or 1+ nodularity on palpation (91% had improvement, 9% had no change, and none had worsening). In 85 US women with clinical and mammographically confirmed fibrocystic disease, complete abstention from methylxanthine consumption resulted in complete resolution of fibrocystic breast disease in 82.5% and significant improvement in 15% of the patients studied.67

Vitamin E and B6 Supplementation

Supplementation with vitamin E (400 to 800 IU) may be beneficial for reducing mastalgia and nodularity of fibrocystic breasts and pyridoxine (vitamin B6/50 to 100 mg) to reduce breast tenderness and pain.68,69 Women are also encouraged to increase dietary fiber and complex carbohydrates, reduce dietary fat to 15% to 20% of their diet, and move toward a more plant-based diet, rich in phytoestrogens. A recent review examined various dietary therapies, and their potential effects in treating fibrocystic breasts.38 The review found that some dietary therapies, including vitamin E and B6, do not have adequate evidence to support their use in fibrocystic breasts. Studies were either of poor quality or had too few study participants to make definitive conclusions. Because of the dynamic nature and very high placebo response (20%) in fibrocystic breast complaints, only well-designed studies with large numbers of participants can address the efficacy of these treatments. Indeed, better-designed studies of vitamin E have all showed no significant effect on any parameter of fibrocystic breast. Studies on reducing caffeinated products from the diet have been variable, some showing positive outcome, others showing no benefit at all. This review found no studies that had examined the effect on fibrocystic breasts of low-fat diets, increased dietary fibers, soy isoflavones, or a more plant-based diet. However, there are considerable mechanistic data, including increasing unabsorbable estrogen conjugates for excretion, reducing the recirculation of estrogen, and positively affecting bowel microflora populations that support the use of these dietary strategies. The general health benefits of adjunct therapies such as adding vitamin E, reducing poor-quality fat intake, or reducing caffeine consumption suggest that these may be worthwhile strategies to try.38

ADDITIONAL THERAPIES

Exercise

It is important to evaluate whether women with breast pain are exercising appropriately and properly. Some women who believe that they are experiencing breast pain or tenderness are instead having chest wall pain, often resulting from inappropriate or overexercise, especially strength-building exercises that emphasize the pectoral muscles.39 No studies have examined the impact of any type of exercise on the symptoms or nodularity of fibrocystic breasts. Consequently, it is difficult to know what duration, type, or frequency of exercise would most benefit women with fibrocystic breasts.

Clothing

Inadequate support of the breasts is thought to lead to suspensory ligament strain, which may cause or contribute to pain and tenderness.55 No randomized controlled studies have examined breast support and its relationship to breast pain.

Stress Reduction

No studies have examined the effect of stress, anxiety, depression, or sleep disturbances on fibrocystic symptoms. However, many other pain syndromes, including fibromyalgia and vulvar pain, are closely associated with levels of “distress” in a woman’s life.70 No randomized clinical trials have been conducted using acupuncture for fibrocystic breast symptoms; however, several open label trials have found that up to 95% of women’s mastalgia was improved after acupuncture treatment.

TREATMENT SUMMARY FOR FIBROCYSTIC BREASTS AND BREAST PAIN

ENDOMETRIOSIS

Amanda McQuade Crawford, Aviva Romm

Endometriosis is one of the most common gynecologic problems in the United States and a leading gynecologic cause of both hospitalization and hysterectomy.25,71,72 Women with symptomatic endometriosis face chronic and sometimes debilitating pain; asymptomatic and symptomatic women alike may experience significant fertility problems due to this condition. The least-biased estimate for the overall prevalence of endometriosis in reproductive-age women is about 10%.73 Endometriosis is defined as the presence and growth of endometrial tissue in locations outside of the uterus. These cells may appear on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, bowel, bladder, peritoneal tissue, ligaments, or other structures in the abdominal cavity, and rarely may occur at other sites, including the nasal and respiratory passages leading to nosebleeds or pink frothy sputum at the time of the menses. Displaced endometrial tissue responds to cyclic hormonal changes, proliferating and shedding outside of the uterus. The bleeding is accompanied by inflammation caused by irritation of local tissue, such as, the peritoneum. Recurrent inflammation can cause scarring and adhesions that can cause pain and dysfunction of other affected sites. Endometriosis is common in women between menarche and menopause, and is associated with as many as 25% of cases of infertility; however, causality has not been definitively established.3,73

Endometriosis occurs across all socioeconomic and ethnic populations, is more common in women who experience early menstruation and fewer than two pregnancies, is associated with menstrual cycle length greater than 30 days, and is more prevalent in women with IUD use greater than 2 years (Box 7-2). Studies demonstrate that women who have experienced repeated vaginal and uterine infections have higher rates of endometriosis than the general population.3 Women with a mother or sister with endometriosis are more likely to suffer from severe endometriosis, suggesting a genetic predisposition; however, milder forms do not always have familial association. The literature is conflicting on the relationship between oral contraceptive (OC) use and the risk of endometriosis. A 1993 review by Vercellini et al. showed that four prospective investigations found a nonsignificant reduction in risk of up to 20%.74 Of three case control studies, two suggested an increased risk and one indicated a reduced risk of developing endometriosis with OC use. The 1994 analysis of the Oxford Family Planning Association OC study found a significantly reduced risk of endometriosis in current OC users. The researchers found that OCs were associated with a 60% reduction in endometriosis. The risk of endometriosis was significantly related to age with the highest risk occurring at ages 40 to 44 years when compared with women ages 25 to 29 years. On the other hand, the risk of endometriosis was elevated among women who formerly used the pill by almost twice the rate of women who had never used OCs. 75 76 77

Multiple theories exist on the etiology of this condition, including retrograde menstrual flow, lymphatic flow theory, and de novo origin. In fact, Konickx et al. propose that mild endometriotic lesions are common and to some extent normal at varying times in all women, and that it is symptomatic, aggressive, or deeply infiltrating endometriosis that should be considered a disease.78 Retrograde menstrual flow theory describes menstrual or endometrial tissue flowing backward through the fallopian tubes and into the abdominal cavity. Lymphatic flow theory suggests the spread of endometrial tissue throughout the body via the lymphatic system. Some researchers postulate that coelomic metaplasia, a de novo origin, might be induced by pathologic processes as a result of chemical exposure. A role for oxidative stress has also been suggested as one of the contributing factors for the development of endometriosis, possibly as part of a conglomeration of factors that pair immunologic and inflammatory factors in its etiology.79,80

There is substantial evidence that immunologic factors play a role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis and endometriosis-associated infertility, and that there is a bidirectional relationship between the endocrine and immune systems.81 In early endometriosis, elevated levels of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, lymphocytes, and macrophages can be identified in the peritoneal fluid. Immune alterations include increased number and activation of peritoneal macrophages, decreased T-cell reactivity and natural killer cell cytotoxicity, increased circulating antibodies, the presence of autoantibodies, and changes in the cytokine network. Decreased natural killer cell cytotoxicity leads to an increased likelihood of implantation of endometriotic tissue. In addition, macrophages and a complex network of locally produced cytokines modulate the growth and inflammatory behavior of ectopic endometrial implants.79, 82 83 84 There also may be a positive correlation between immunosuppression and disease progression in the presence of established disease.85,86 Further, women with endometriosis appear to have higher rates of atopic conditions and susceptibility to opportunistic infections (e.g., candidiasis) than women who do not have endometriosis.87

SYMPTOMS

The following symptoms (Box 7-3), alone or in constellations, should alert a woman and her practitioner to the possibility of endometriosis: premenstrual pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, generalized pelvic pain throughout the month without other explanation, atypical periods, nausea, vomiting, exhaustion, bladder problems, frequent infections, dizziness, painful defecation, rectal pain, low backache, irritable bowels, or infertility. The far-reaching nature of these symptoms and their possible association with other conditions helps to explain why this condition is difficult to diagnose. Dysmenorrhea and painful intercourse become even more suggestive of endometriosis if they begin after a history of relatively pain-free menstruation and intercourse. Severity of pain is not indicative of the severity of the condition, with the exception of severe pain, which is associated with extensive endometriosis and adenomyosis (deeply infiltrating endometriosis.)3,78 Other causes of pelvic and abdominal pain or bleeding must be ruled out.

DIAGNOSIS

Endometriosis is most commonly seen in women 30 to 40 years old and is rarely found in postmenopausal women. Endometriosis has been thought not to occur prior to menarche; however, the rates of this condition are increasing among teenagers.3 The site of lesions, although widely variable, is generally the posterior cul de sac or ovaries. Diagnosis is based on pelvic examination, diagnostic ultrasound, or laparoscopy, with definitive diagnosis based on laparoscopy. CA-125 is a serum antigen found in endothelial cervical cancer that can also be found to be elevated in women with endometriosis. The diagnostic importance of the test for endometriosis is still uncertain; however, there appears to be some predictive value demonstrating which women might benefit from specific treatments on the basis of CA-125 levels, and CA-125 levels may indicate whether improvement is occurring.88 Endometriosis is staged based on the location(s) of the endometrial tissue as follows:

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Medical treatment of endometriosis includes both pharmaceutical and surgical approaches. Pharmaceutical treatments provide only suppression of the disease; they do not exact a cure.3 Decisions regarding treatment are based on endometriosis severity and staging, symptom picture, and ultimately, the woman’s needs and goals, for example, desire for children in the future.89 For women experiencing mild symptoms (or none) and for women who are close to menopause, the appropriate treatment may be to do nothing.78 For women with mild to moderate symptoms, and those who desire pregnancy, the appropriate pharmacologic therapy should be considered, and if necessary, can be combined with conservative surgery. It should be noted that, in spite of medical treatment, endometriosis has a high recurrence rate of 5% to 20% unless total hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy are performed. With pharmacologic interventions, pain typically resumes upon cessation of medications, although initially with pain that is less intense than prior to treatment. Pain relief, pregnancy rates, and recurrence rates are similar with all treatment methods. The goal of pharmaceutical treatment is to interrupt patterns of endometrial stimulation and bleeding.89 Pharmaceutical options include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and hormonal therapies (progestins, GnRH analogs, Danazol, and oral contraceptives). NSAIDs (i.e., ibuprofen, naproxen) may be prescribed for mild to moderate pain. They are relatively safe for short-term symptomatic relief; however, long-term use can lead to health consequences, including gastrointestinal bleeding, and should be avoided in patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease or renal failure. It should be noted that none of these therapies demonstrates significant benefit over the others, and all are associated with a high recurrence rate (20%–50%) upon discontinuation of the therapy.89 Progestins (medroxyprogesterone acetate, i.e., Depo-Provera) suppress the response of endometrial tissue to cyclic hormones, leading to atrophy of this tissue and decreased pain. They are typically better tolerated than oral contraceptives (OCs), with fewer side effects, and are less costly than Danazol and GnRH analogs. This is often considered the pharmaceutical treatment of choice for endometriosis, although the FDA no longer supports the use of Depo-Provera for this purpose. Side effects include weight gain, fluid retention, and breakthrough bleeding. Depression is a common significant side effect of medroxyprogesterone use. In high doses, medroxyprogesterone can adversely affect lipid profiles, and may lead to a state of hypoestrogenism, with subsequent potential for bone loss. Oral contraceptives are used to control pain in women not desiring pregnancy. The combined effect of estrogen and progesterone is to induce a state of “pseudopregnancy,” and appears to lead to a 90% rate of improved symptoms with long-term use. Side effects include all those typically associated with general OC use. Danazol, a synthetic testosterone, is used for the treatment of mild to moderate endometriosis in women who desire fertility but not necessarily in the immediate future. It induces a state of “pseudomenopause,” eliminating mid-cycle FSH and LH surges. Once considered the optimal treatment for endometriosis, it is now considered no more effective than any of the other pharmaceutical treatments. Possible side effects include weight gain, fluid retention, fatigue, decrease in breast size, hirsutism, atrophic vaginitis, hot flashes, muscle cramps, emotional fluctuations, voice changes, spotting, and decreased HDL cholesterol levels. In some patients it may cause hepatocellular damage; thus is contraindicated in patients with liver disease, and liver enzymes should be monitored in all patients during treatment. It is also contraindicated in patients with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, congestive heart failure, renal impairment, and pregnancy.3,25,89,90 Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRH-a, e.g., Leuprolide) also cause a suppression of endometriosis via a “pseudomenopausal” state. GnRH treatment does not carry the same risks of negative impact on serum lipids and lipoproteins compared with Danazol; however, it does interfere with calcium metabolism via stimulation of a hypoestrogenic state, and thus can cause osteoporosis. Even after only 6 months of use, a 6% to 8% loss in trabecular bone has been observed. It can take up to 2 years after cessation of treatment to replace this bone loss; thus a treatment is usually restricted to 6-month durations.3,91

Surgical options include conservative surgery (destruction and removal of endometriomas while maintaining reproductive function) and radical surgery (hysterectomy, generally accompanied by bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). Conservative treatment involves the removal of endometriotic lesions and restoration of normal anatomical relationships via removal of adhesions to the greatest extent possible, with the goal of pain relief, and possible restoration of fertility when achieving pregnancy is desired and has been impaired by the condition. In approximately one-fourth of women treated surgically, however, there is no improvement in fertility even if the disease was considered mild. Procedures include knife excision, laser surgery, electrocautery, curettage, and laparotomy. The worse the disease, the worse the statistics for conceiving after surgery.92,93 Recurrence of endometriosis after surgery is dependent on the skill of the surgeon and extent of disease, and as with other endometriosis treatments, rates may be as high as 20%. Hysterectomy will not remove lesions outside the uterus and is not considered a successful treatment when used primarily to reduce the symptom of chronic pelvic pain. Surgery carries the risk of complications, especially adhesion formation and continuing pain. The total rate at which symptoms of chronic pelvic pain returned after drug treatment is estimated to be 5% to 15% at the end of 1 year, or up to 50% at the end of 5 years. Nonetheless, the risks of surgery or medication may be justifiable for severe pain that does not respond to other methods, especially if menopause is not expected for some time. There is a concern that diagnostic microsurgery may aggravate or cause the transfer of viable endometrial cells into general or lymphatic circulation, thereby causing the very condition being identified. Because of this, some wary clients choose natural treatment approaches for the condition without a certain diagnosis, believing that if the signs and symptoms respond, the holistic prescription was correct for the presumed diagnosis.

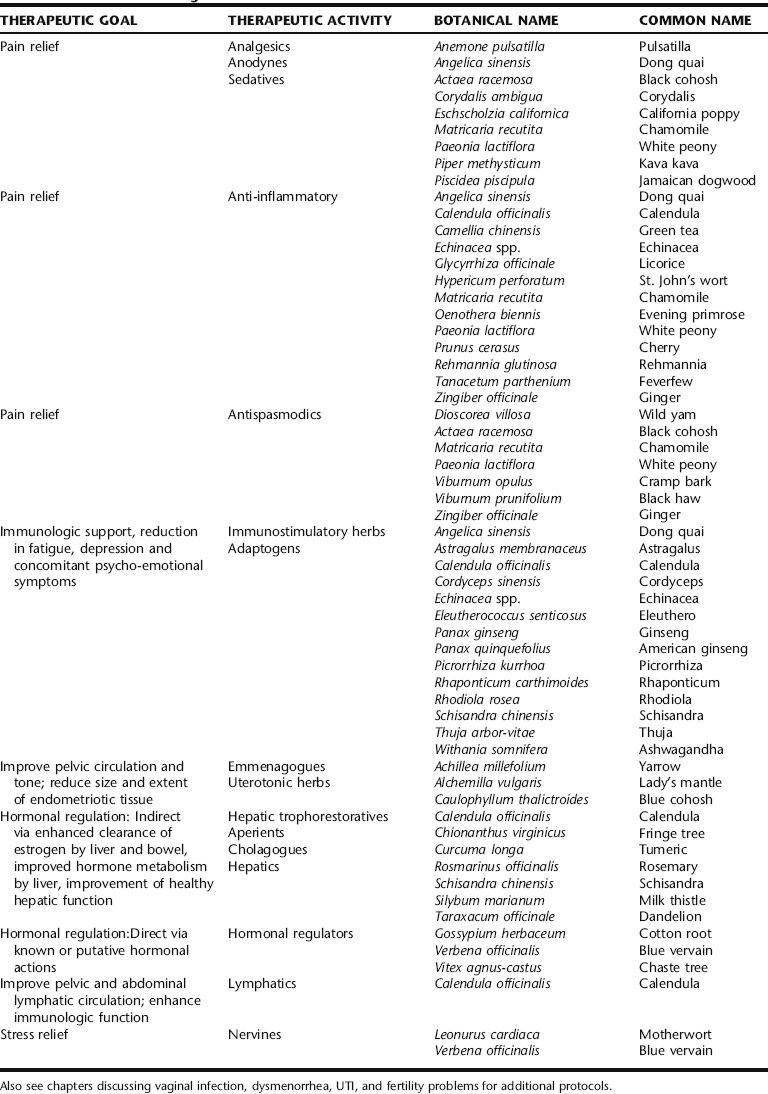

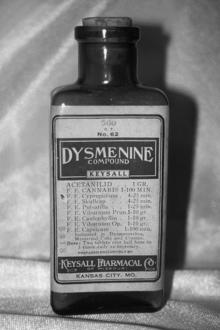

BOTANICAL TREATMENT

Herbalists share the conventional medical perspective that endometriosis has multifactorial causes. The botanical approach, however, takes into consideration immune dysregulation, inflammation, hormonal dysregulation, diet and nutritional status, lifestyle, exposure to exogenous estrogens, and the woman’s emotional and psychological mechanisms for coping with this condition as components of a whole picture. Given that nonradical medical treatments for endometriosis are purely suppressive rather than curative, the high recurrence rate of endometriosis upon cessation of pharmaceutical treatment, and the potential for drug-related or surgical side effects, botanical medicines may provide women with a safe alternative for symptomatic pain relief, reduction of inflammation, prevention and reduction of recurrent vaginal and pelvic infections, stress reduction, and improvement of overall immunologic health (Table 7-4). By applying a comprehensive natural health care protocol, many cases of endometriosis can also be resolved. The herbal approach should also include as part of the protocol, herbs that address concomitant discomforts arising from the condition, such as irritable bowel complaints or depression.

DISCUSSION OF BOTANICALS

For many women with endometriosis pain is the single most debilitating aspect of this condition (other than chronic fertility problems in women desiring pregnancy). Therefore, pain management should be an important focus in the care of women with this condition. Herbalists reliably employ a number of herbs for the treatment of pelvic and abdominal pain, many of which have a long history of traditional use for painful gynecologic conditions. These herbs can be used singly but are generally used in various combinations with other herbs in these categories, or as part of a larger protocol. Analgesic herbs are used for generalized or local pain of an aching or sharp quality and include black cohosh, black haw and cramp bark, chamomile, corydalis, pulsatilla, dong quai, ginger, and Jamaican dogwood. Corydalis, Jamaican dogwood, and pulsatilla are especially dependable for moderate to serious pain. Pulsatilla is considered specific for ovarian pain.22 Antispasmodics are typically used for cramping pain, but also may be used for sharp or dull pain, aching, and drawing pains in the lower back and thighs, and include, such as wild yam, the viburnums (cramp bark and black haw), black cohosh, chamomile, and ginger. Dong quai’s traditional TCM uses for gynecologic conditions, specifically for conditions of blood vacuity and stasis, the latter of which endometriosis may be considered among, along with its antispasmodic, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory qualities, make it an important herb to consider.25,50,94 Many antispasmodics and anti-inflammatories, such as wild yam, the viburnums, ginger, and chamomile are specific not only for uterine pain, but also for intestinal, bowel, and urinary pain and irritability, making them uniquely suitable for endometrial pain and accompanying bowel and bladder discomforts. This is important to keep in mind, because the pain of endometriosis is related to irritation of tissue by endometrium outside of its normal site in the uterus. Sedatives are useful when there is the need to induce deep rest or sleep to obtain pain relief, and include

Formula for Treatment of Mild to Moderate Pain Associated with Dysmenorrhea

| Black cohosh | (Actaea racemosa) | 20 mL |

| Cramp bark | (Viburnum opulus) | 20 mL |

| Chamomile | (Matricaria recutita) | 15 mL |

| Dong quai | (Angelica sinensis) | 15 mL |

| Wild yam | (Dioscorea villosa) | 15 mL |

| Licorice | (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | 10 mL |

| Ginger | (Zingiber officinale) | 5 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

Formula for Treatment of Moderate to Severe Pain Associated with Dysmenorrhea

| Black cohosh | (Actaea racemosa) | 25 mL |

| Cramp bark | (Viburnum opulus) | 25 mL |

| Wild yam | (Dioscorea villosa) | 20 mL |

| Corydalis | (Corydalis ambigua) | 15 mL |

| Jamaican dogwood | (Piscidea piscipula) | 15 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

California poppy, a combination of black cohosh and cramp bark, or a combination of cramp bark and Jamaican dogwood. Valerian and hops are also useful sedatives. The successful use of these herbs for pain depends largely upon adequate dosing and frequency of administration.

Immunomodulation

The exact immunologic underpinnings of endometriosis remain uncertain. There appears to be a complex interplay of hyperimmune, autoimmune, and hypoimmune function at work, either variably or concurrently-leading only to the clear understanding that there is some level of immune dysregulation that accompanies this condition. The most appropriate response seems to be twofold: (1) to look at the unique constellation of symptoms presented by each individual woman, for example, whether she is depleted and susceptible to frequent colds and repeated vaginal infections or chronic atopic conditions—and to treat accordingly, and (2) to provide botanicals which support immune regulation—notably, the adaptogens. For women who evidence a state of immune depletion in combination with endometriosis some amount of immunostimulation may be appropriate to bolster the overall immune response, and may be provided through the use of herbs such as echinacea, astragalus, or Picrorrhiza kurrhoa in combination with adaptogens such as ashwagandha, American ginseng, rhaponticum, or rhodiola. These women also may benefit greatly from medicinal mushrooms such as Reishi and Cordyceps for immune support. For women with signs of hyperimmunity, atopic conditions such as eczema or chronic rhinitis, or autoimmunity, the use of immunosupportive anti-inflammatory adaptogens may be most appropriate, such as licorice, ashwagandha, and American ginseng. It is unknown and a matter of great debate as to whether immunostimulating herbs such as echinacea and astragalus are safe and appropriate for use when there is autoimmunity.22 Using adaptogens for treating endometriosis makes sense in that their actions simultaneously influence and restore normalcy to the functions of the immune system and the HPA axis, both of which appear to have dysregulated function in this condition. The uterine endometrium is a complex structure of interspersed glandular tissue and endometrial stroma, closely associated with lymphoid tissue.81 The inclusion of herbs that are traditionally thought to improve lymphatic circulation, such as calendula, echinacea, cleavers, and pokeroot, are commonly included in botanical protocol for endometriosis.

Anti-Inflammatories and Antioxidants

Inflammation is a hallmark of endometriosis, and as discussed, free radical damage may be part of the etiology of this disorder. It has been suggested that growth factors and inflammatory mediators produced by activated peritoneal leukocytes participate in the pathogenesis of endometriosis by facilitating endometrial cells growth at ectopic sites.81 Elevated levels of inflammatory cells and mediators such as peritoneal macrophages, prostaglandins, proteolytic enzymes, complement fragments, IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) have been identified in the peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis.81 Numerous herbs that have been used traditionally for inflammatory types of conditions demonstrate significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects and should be considered for use in formulations for treatment and symptomatic relief, along with herbs whose use for inflammation is only recently being discovered. These are discussed in the following.

Dong Quai

Dong quai has antispasmodic, analgesic, and tonic effects, and has demonstrated significant antioxidant and free radical scavenging actions, partially through inhibition of anion radical formation. Limited animal and in vitro studies have reported on the specific immunomodulatory effects of dong quai, including a stimulation of phagocytic activity and interleukin-2 (IL-2) production, and an anti-inflammatory effect. There is evidence to suggest that the polysaccharide fraction of dong quai may contribute to these effects. Immunostimulatory and anti-inflammatory effects have also been documented for isolated ferulic acid. Dong quai has been traditionally used in Chinese medicine for the treatment of “blood stasis,” which encompasses a diagnosis of endometriosis.

Echinacea

Echinacea is widely used by herbalists for its immunostimulatory and anti-inflammatory effects, to support and promote the body’s natural immune responses.25,95,96 Antioxidant effects appear to include free radical scavenging mechanisms and transition metal chelating, whereas immunostimulating effects include enhanced phagocytosis, and the stimulation of cytokine and immunoglobulin production.29,97

Feverfew

Feverfew has been used for the treatment of menstrual complaints since at least the time of the ancient Greeks. In fact, its botanical name may reflect such use—parthenos means “virgin” in Greek.98 It is mentioned by the Eclectic physicians for use in the treatment of menstrual irregularity.99 Feverfew also has been used for the treatment of other inflammatory conditions, including headache, fever, psoriasis, and arthritis. Although studies have not been done on the use of this herb in the treatment of endometriosis, and indeed, it is not widely discussed for such use even in the herbal literature, its pharmacology and actions as an antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory suggest that consideration of such use is warranted.100 Feverfew has exhibited inhibition of prostaglandin synthetase, which inhibits the conversion of arachidonic acid to inflammatory prostaglandins, inhibits mast cell degranulation and subsequent histamine and serotonin release, and has shown inhibition of other inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, NFκB, and IFN-γ, as well as inhibiting peritoneal cyclooxygenase in animal models.97

Ginger

Herbalists use ginger root as an anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic herb for the treatment of numerous painful inflammatory conditions from arthritis to dysmenorrhea.101,102 No studies have been identified for its use for painful gynecologic complaints. One trial of 120 women reported ginger to be an effective antiemetic for the treatment of postoperative nausea, with specific trials demonstrating its efficacy in reducing postlaparoscopic gynecologic procedures. However, two other trials demonstrated either no effect compared to placebo, or negative effect (increased nausea) with increased doses of ginger.97 Ginger remains popular among Western and TCM herbalists as an antispasmodic treatment for dysmenorrhea.25 It is taken in tincture form in combination with other herbs, in infusions, and also used externally as a poultice and in baths for pelvic discomfort.

Gotu Kola