Complications of surgery

Introduction

Any operation, major trauma or other surgical admission may be attended by complications, many of which are preventable. Complications cause added pain and suffering and may even put the patient’s life at risk. Also, an anastomotic leak or a wound dehiscence can double the cost of an elective colonic resection.

While some complications are to some extent inherent in the condition being treated (e.g. deep venous thrombosis following lower limb fractures) or arise from some co-morbid (pre-existing) condition such as myocardial ischaemia, others arise from failure to visit or examine a patient when called, errors of judgement (e.g. misdiagnosis), poor nursing practice (e.g. allowing pressure sores to develop) or even frank negligence (e.g. operation on the wrong side). Poor communication between hospital staff is a frequent cause of avoidable complications, for example failing to record important events in the patient’s treatment (and the date or name of the doctor), or to record a drug allergy in the case record, or neglecting to inform the operating department about a late change to an operating list.

A large proportion of complications can be prevented or minimised by anticipation, by taking prophylactic measures, by attention to detail and by early recognition and treatment of problems as they develop. With potentially serious complications (e.g. bowel anastomotic leak), early diagnosis and reoperation is crucial, as delay often leads to catastrophic ‘snowballing’ sepsis and multi-organ failure. Once two or more body systems become impaired, survival falls to only about 50%. If, for example, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and renal failure complicate an operation for obstructive jaundice in a patient with liver impairment, the odds are heavily stacked against survival.

In operative surgery, complications can be either those of any operation or specific complications of individual operations. Both groups can be subdivided into immediate (during operation or within the next 24 hours), early postoperative (during the first postoperative week or so), late postoperative (up to 30 days after operation) and long-term.

Surgical complications fall into the five broad categories listed in Box 12.1. ‘Medical’ complications are discussed in Chapter 8. Complications of specific operations are discussed in Chapters 18–51, as appropriate.

Complications of anaesthesia

The main complications of anaesthesia are summarised in Box 12.2.

General complications of operations

The main complications of any operation are: inadvertent trauma to the patient in the operating department, haemorrhage, surgical damage to related structures, inadequate operation, infection and problems with wound healing.

Inadvertent trauma in the operating department

Patients are at risk of injury during transport or transfer in the operating department, especially when under anaesthesia. Staff involved in handling patients are also at risk of injury, for example to the back.

The most common causes of trauma in the operating theatre are:

• Injuries resulting from falls from trolleys or from the operating table during positioning

• Injury to diseased bones and joints from manipulation or positioning. These include dislocation of rheumatoid atlanto-axial joints and dislocation of a prosthetic hip joint

• Ulnar, lateral popliteal and other nerve palsies resulting from pressure

• Electrical burns from wet or poorly contacting diathermy pads or misuse of the diathermy probe

• Excess pressure on the calves causing deep venous thrombosis

Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage occurring during an operation (primary haemorrhage) should be controlled by the surgeon before the operation is completed.

Early postoperative haemorrhage

Haemorrhage immediately after operation usually indicates inadequate operative haemostasis or a technical mishap such as a slipped ligature or unrecognised blood vessel trauma. Occasionally it is due to a bleeding disorder.

If an operation involves major blood loss and large volume transfusion of stored blood, haemorrhage may be perpetuated by consumption coagulopathy, in which platelets and coagulation factors have been ‘consumed’ in a vain attempt at haemostasis. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) can be one facet of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) with widespread intravascular thrombosis and exhaustion of clotting factors. Occasionally bleeding results from preoperative use of aspirin or aspirin-like drugs (responses vary greatly between patients), uncontrolled anticoagulant drugs or, less commonly, a pre-existing but unrecognised bleeding disorder. Any patient giving a history of excess bleeding should have a platelet count and coagulation screen checked before operation.

Operations at particular risk of early postoperative haemorrhage include:

• Major operations involving highly vascular tissues such as the liver or spleen

• Major arterial surgery, especially ruptured aortic aneurysm (large volume blood loss may occur, and the patient may be heparinised during operation)

• Operations which leave a large raw surface such as abdomino-perineal excision of rectum

This type of postoperative haemorrhage has been traditionally described as reactionary in the belief that it was a ‘reaction’ to the recovery of normal blood pressure and cardiac output. This concept is probably misleading and should now be discarded, especially since it may hinder the decision to reoperate urgently.

Management of early postoperative haemorrhage: This is really a form of primary haemorrhage and, if substantial, the patient must be surgically re-explored and the source treated as at the original operation. It is wise to perform a clotting screen (including platelet count) and order bank blood as a preliminary measure. Good intravenous access should be ensured. If heparin was used at the original operation, protamine can reverse any residual activity. If the clotting screen is abnormal, infusions containing clotting factors may be needed, as advised by a haematologist. Many patients will stop bleeding with supportive measures and blood transfusion but re-exploration must be seriously considered at every stage.

Later postoperative haemorrhage

Haemorrhage occurring several days after operation is usually caused by infection eroding blood vessels near the operation site; this is known as secondary haemorrhage. Treatment involves managing the infection, but exploratory operation is often required to ligate or suture the bleeding vessels.

Surgical injury

Anatomical structures, particularly nerves, blood vessels and lymphatics, may be unavoidably damaged during operation. This is particularly true in cancer surgery, illustrated by facial nerve excision during total parotidectomy. If anticipated, the probability must be discussed with the patient beforehand (ideally by the surgeon performing the operation) and accepted as part of the operative risk. Sometimes the integrity or location of vulnerable structures can be established before operation, allowing better planning of the operation. For example, indirect laryngoscopy may be done to assess vocal cord integrity prior to thyroid surgery.

Inadvertent tissue damage

Structures may be inadvertently damaged during operation. Examples include recurrent laryngeal nerve damage during thyroidectomy, or trauma to bile ducts during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The main factors are inexperience, anatomical anomalies, attempts at arresting precipitate haemorrhage and tissue planes obscured by inflammation or malignancy. Signs of damage to structures at particular risk should be sought in the postoperative period; for example, hoarseness after thyroidectomy or jaundice after cholecystectomy.

Infection related to the operation site

The most common infective complication is a superficial wound infection within the first postoperative week. This relatively trivial infection presents as localised pain, redness and a slight discharge. Organisms are usually staphylococci derived from skin and the infection usually settles without treatment. The exception is the patient into whom a prosthesis such as an arterial graft or artificial joint has been inserted. For these, antibiotics must be given to prevent the devastating consequences of infection around the prosthesis.

Wound cellulitis and abscess

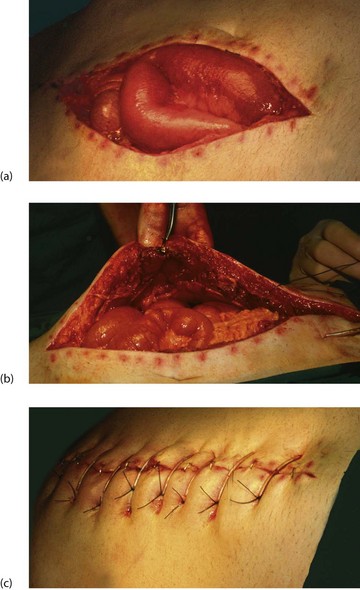

More severe wound infections occur most often after bowel-related surgery, when staphylococci (meticillin-sensitive or resistant varieties) or faecal organisms are usually incriminated. Most present in the first postoperative week but they may occur as late as the third week, sometimes after leaving hospital. These infections commonly present with a pyrexia; wound examination reveals spreading cellulitis or localised abscess formation (Fig. 12.1).

Fig. 12.1 Abdominal cellulitis

This woman of 73 presented with faecal peritonitis caused by a diverticular perforation of the sigmoid colon. She was resuscitated and underwent a laparotomy and sigmoid loop colostomy (note bag), without resection of the perforation. She remained toxic with a high fever and tachycardia, and developed spreading cellulitis in the right groin and flank. This proved to be due to continuing leakage from the perforation. Nowadays, a Hartmann’s operation or resection and primary anastomosis is performed so there is no longer a perforation leaking faecal matter into the peritoneal cavity

Cellulitis is treated with antibiotics after taking a wound swab for culture and sensitivity, whereas a wound abscess is treated by surgical drainage. This may simply involve suture removal and wound probing, but deeper abscesses may need re-exploration under general anaesthesia. In either case, the wound is left open afterwards to heal by secondary intention (see Fig. 12.2).

Intra-abdominal infection is discussed under complications of abdominal and bowel surgery later in this chapter.

Gas gangrene

Gas gangrene is an uncommon acute, life-threatening wound infection in which the anaerobic organisms multiply in necrotic tissue, particularly muscle (see Ch. 3, p. 48).

Late infective complications

A late infective complication of surgery is a chronically discharging wound sinus emanating from a deep chronic abscess. It usually relates to foreign material such as a non-absorbable suture or mesh or sometimes necrotic fascia or tendon. These sinuses commonly follow wound infections where healing is delayed and incomplete. Wound sinuses occasionally appear after apparent normal healing, particularly after insertion of a prosthesis.

Sinuses rarely heal spontaneously unless the foreign material is discharged, and the usual treatment is therefore wound re-exploration and removal of the offending substance. In groin sinuses following aortofemoral bypass grafts, removal of the graft would impair the arterial supply of the lower limb and the infected graft must be replaced or bypassed.

Impaired healing

Factors retarding wound healing

Nearly all wounds heal without complication. It is untrue that wounds heal slowly in the elderly; this is so only when there are specific adverse factors or complications. Wound healing in general is retarded if blood supply is poor (as in lower limb arterial insufficiency) or if the wound is under excess tension. Other retarding factors are infection, long-term corticosteroid therapy, immunosuppressive therapy, previous radiotherapy, severe rheumatoid disease, smoking, global malnutrition and specific vitamin and mineral deficiency, especially of vitamin C and possibly zinc.

Wound dehiscence (‘burst abdomen’)

Wound dehiscence, i.e. total wound breakdown, is uncommon. It affects about 1% of abdominal wounds, usually about 1 week after operation, and is preceded by profuse sero-sanguinous fluid discharge from the wound. The sudden bursting open of the abdomen revealing coils of bowel is alarming but is remarkably pain-free. Infection and other factors already described may play a part but the usual cause is inadequate abdominal wall repair, often in the presence of infection or malnutrition. This may be compounded by mechanical disruption caused by coughing or abdominal distension.

The wound should be covered with sterile swabs soaked in saline and the patient returned to the operating theatre within a few hours for repair. This usually involves placement of tension sutures incorporating large ‘bites’ of the whole thickness of the abdominal wall (see Fig. 12.3).

Incisional hernia

Incisional hernia is a late complication of abdominal surgery. These usually become apparent within the first postoperative year but sometimes develop as long as 15 years later; the overall incidence is about 10–15% of abdominal wounds. The hernia is caused by breakdown of the abdominal wall muscle and fascial repair. Predisposing factors are abdominal obesity, diabetes, smoking, abdominal distension and poor muscle quality, poor choice of incision, inadequate closure technique, postoperative wound infection and multiple operations through the same incision.

An incisional hernia usually presents as a bulge in the abdominal wall near a previous wound. They are usually asymptomatic but occasionally a narrow-necked hernia presents with pain or strangulation. Once an incisional hernia has appeared, it tends to enlarge progressively and may become a nuisance cosmetically or for dressing (see Fig. 12.4). Repair is indicated for strangulation, pain or inconvenience and usually involves placing a synthetic mesh at open operation or laparoscopically.

Complications of any surgical condition

Up to 15% of patients having major operations and general anaesthesia suffer from respiratory complications. The most common are atelectasis and pneumonia. Pre-existing lung disease greatly increases the risk. Severely ill patients, including those with acute pancreatitis, and burns or trauma victims, are susceptible to acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Effects of anaesthesia and surgery on respiratory function

Anaesthesia and surgery predispose to postoperative complications by altering lung function and compromising normal defence mechanisms, as follows:

• Lung tidal volume—may be reduced by as much as 50%, depending on the incision site; thoracic, upper abdominal and lower abdominal incisions reduce lung volume in decreasing order of effect

• Lung expansion—reduced by the supine position during and after operation, pain, abdominal distension, abdominal constriction by bandages and the effects of sedative drugs

• Ventilation rate—usually increases and there is loss of normal periodic hyperinflation

• Diminished ventilation and pulmonary perfusion—result in reduced gaseous exchange

• Airway defences—compromised by loss of the cough reflex and diminished ciliary activity, which both lead to accumulation of secretions

• Problems associated with laparoscopic abdominal surgery—the pneumoperitoneum and head-down position lead to diaphragmatic splinting, a reduction in functional residual capacity and changes in intrathoracic blood volume. These lead to atelectasis, pulmonary shunting and hypoxaemia. Raised ventilatory airways pressure may lead to pulmonary barotrauma

Atelectasis

Pathophysiology and clinical features: Atelectasis or alveolar collapse occurs when airways become obstructed and air is absorbed from air spaces distal to the obstruction. Bronchial secretions are the main cause. Predisposing factors include shallow ventilation, loss of periodic hyperinflation, inhibition of coughing and pooling of mucus. All of these are greater problems after thoracic and upper abdominal surgery. The resulting ventilation/perfusion mismatch produces a degree of right-to-left shunting of blood, which causes a fall in PaO2. If obstructed airways are small, causing minor segmental collapse, localising signs are minimal and X-ray appearance is unremarkable. Despite this, the overall extent of collapse may be large and cause significant hypoxaemia.

Obstruction of a major airway causes collapse and consolidation of a whole lobe, resulting in the typical signs of dullness to percussion and reduced breath sounds or bronchial breathing. Chest X-ray shows the lobe is contracted and opacified, with mediastinal shift and compensatory expansion of other lobes.

Most cases of atelectasis are mild and pass undiagnosed, although the patient may be slow to recover from operation. The patient may be cyanosed, resulting from mild hypoxaemia, and have a mild tachypnoea, tachycardia and low-grade pyrexia, which all resolve spontaneously within a few days. Sputum culture (if any is produced) is usually negative but infection may complicate severe cases.

Prevention and treatment of atelectasis: In patients undergoing major surgery, atelectasis is best prevented by preoperative and postoperative physiotherapy. This includes deep breathing exercises, regular adjustments of posture and vigorous coughing. During physiotherapy, wounds should be supported with the patient’s hand. Effective analgesia, e.g. infiltration of the wound with local anaesthetic or epidural analgesia, facilitates physiotherapy and mobility. Nebulised bronchodilators such as salbutamol may assist the patient to cough up secretions. Severe cases of diffuse atelectasis may require non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation. Lobar or whole lung collapse requires intensive physiotherapy and sometimes flexible bronchoscopy to aspirate occluding mucus plugs.

Pneumonias

Bronchopneumonia is often seen in surgical patients. It occurs secondarily to chronic lung disease, smoking or following atelectasis or aspiration of gastric contents. Haemophilus and Streptococcus pyogenes are the common infecting organisms but coliforms may be responsible in elderly, debilitated or seriously ill patients. Pseudomonas bronchopneumonia occurs in patients on ventilators or with bronchiectasis.

Infection is manifest by pyrexia, tachypnoea, tachycardia and a raised leucocyte count. The mucopurulent sputum is thick, copious and green. Antibiotics, usually amoxicillin or co-trimoxazole, are given on a ‘best-guess’ basis until sputum culture and sensitivities are available. Physiotherapy, mobilisation and encouragement to cough are all important for recovery.

Aspiration pneumonitis: Aspiration pneumonitis (Mendelson’s syndrome) is a sterile, chemical inflammation of the lungs resulting from inhalation of acidic gastric contents. There is often a clear history of vomiting or regurgitation, followed by a rapid onset of breathlessness and wheezing. This may later become complicated by infection, i.e. bronchopneumonia, with typical symptoms and signs. Chest X-ray shows characteristic ‘fluffy’ opacities, particularly in the lower lobes, which for anatomical and postural reasons are most affected.

Aspiration occurs when protective laryngeal reflexes are suppressed or when there is intestinal obstruction and regurgitation. Laryngeal suppression may be due to impairment of consciousness (e.g. during recovery from general anaesthesia or in alcoholic intoxication) or loss of consciousness after head injury.

Emergency anaesthesia in the non-starved patient poses special risks. Whenever possible, anaesthesia should be postponed for 4–6 hours after the last food or drink other than water. In accident victims, it is important to note the time of last eating with respect to the accident, and to remember that stress and anxiety may greatly delay gastric emptying., Gastric emptying is also much slower in pregnancy.

A patient with intestinal obstruction is at risk of inhalation of gastric contents. Ideally, the stomach should be emptied by nasogastric tube. If general anaesthesia must be performed on the non-starved or otherwise at-risk patient, a rapid sequence induction is employed: as the patient loses consciousness, an assistant applies cricoid pressure to flatten the oesophagus against the cervical spine, preventing reflux. The airway is then secured with a cuffed endotracheal tube before cricoid pressure is released. Oral antacids may be given beforehand to neutralise acidity. Metoclopramide by injection may also be used to hasten gastric emptying.

Mortality from aspiration pneumonitis approaches 50% and urgent treatment must be started should it occur. This involves thorough bronchial suction via an endotracheal tube (or bronchoscope if necessary), followed by positive-pressure ventilation and prophylactic antibiotics. Intravenous steroids are usually given to limit the inflammatory process, but their efficacy is unproven.

Aspiration pneumonia: Aspiration pneumonia may complicate aspiration pneumonitis, but more often it develops insidiously, following chronic aspiration of infected food and oropharyngeal secretions. In the surgical context, debilitated, confused or elderly patients are the usual victims, but aspiration pneumonia is also seen in alcoholics, drug addicts and stroke patients. Achalasia of the oesophageal cardia and large hiatus hernias can lead to chronic aspiration, particularly at night. The clinical features are of infection and lobar consolidation (usually of the lower lobe) progressing to lung abscess formation. Organisms are usually mixed oral anaerobes sensitive to penicillin, but prognosis depends more on the patient’s general condition and is usually poor.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

This syndrome of acute respiratory failure, formerly known as adult respiratory distress syndrome, is characterised by rapid, shallow breathing, severe hypoxaemia, stiff lungs and diffuse pulmonary opacification on X-ray. It develops in response to a variety of systemic and direct insults to the pulmonary alveoli and microvasculature.

Acute respiratory failure has long been recognised in many disparate conditions and has been given names such as shock lung, wet lung, post-traumatic respiratory insufficiency, Da Nang lung (Vietnam war) and white lung (after the X-ray appearance). Box 12.3 lists the main conditions with which ARDS is associated.

Pathophysiology of ARDS: The lung insults causing ARDS all have the effect of increasing the pulmonary capillary permeability, leading to leakage of protein-rich fluid into the alveolar interstitium. This causes interstitial oedema which in turn reduces lung compliance and causes ‘stiff lungs’ and reduced alveolar ventilation. Release of inflammatory mediators cause these effects.

The alveolar lining cells (type I pneumocytes) are also damaged. This damage, combined with the increased interstitial hydrostatic pressure, causes leakage of fluid into alveolar spaces until they are filled. The result is disruption of the lung ventilation to perfusion ratio (V/Q ratio), in effect causing right-to-left shunting of blood. The intra-alveolar fluid later condenses to form a hyaline membrane which lines the alveoli. This is histologically similar to the neonatal form of the disease.

The full clinical syndrome often takes 24–48 hours to develop after the initial insult. If the patient eventually recovers, the interstitial damage may result in diffuse interstitial fibrosis. It is important to note that cardiac failure is not involved in causing ARDS, but cardiac failure may later complicate it.

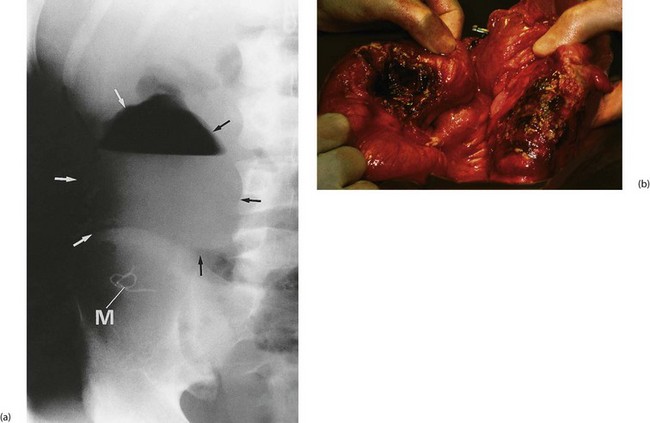

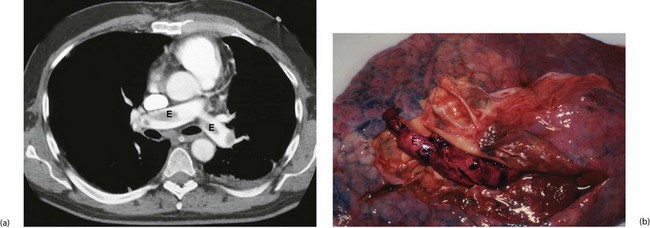

Clinical features of ARDS: The main finding is rapid shallow respiration with only scattered crepitations on auscultation. There is usually no cough, chest pain or haemoptysis. Blood gas analysis reveals low PaO2 but the PaCO2 remains normal except in the most severe cases. Chest X-ray may be normal in the early stages, progressing rapidly through increased interstitial markings to complete or partial ‘white-out’ (see Fig. 12.5). ARDS may be difficult to distinguish from cardiac failure except that cardiac diameter is normal in ARDS, and cardiac failure usually responds to diuretic therapy.

Fig. 12.5 Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

(a) This middle-aged man underwent an oesophagectomy for carcinoma, with the proximal stomach anastomosed to the oesophageal remnant in the chest. He developed ARDS in the early postoperative period. The chest X-ray shows ill-defined alveolar opacification in the lung mid zones. Note the metallic vascular clips on the right side, the chest drain on the left side and the endotracheal tube and central venous line. (b) The CT scan shows bilateral consolidation in the dependent portion of both lungs with ‘ground glass’ opacification in the upper zones. There is a left pneumothorax with a chest drain in situ (arrowed); subcutaneous emphysema E resulting from the thoracotomy is also visible

Treatment of ARDS: The objective is to maintain respiratory function and cardiovascular stability while the underlying cause (e.g. sepsis) is brought under control. This should be carried out in intensive care. The sooner treatment is begun, the greater the chance of recovery.

Most patients require mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) to achieve adequate oxygenation and to try to reverse alveolar oedema and collapse. Fluid balance is complex and requires monitoring of right atrial pressure using a central venous line. Cardiac output can be measured using transoesophageal ultrasound. One of the treatment aims is to produce a negative fluid balance and thus minimise fluid accumulation in the lung and interstitial tissue. Loop diuretic infusions or continuous veno-venous haemofiltration can be used to achieve this. Renal insufficiency is a common association, and can also be treated by haemofiltration. Diuretics do not control pulmonary oedema but instead aggravate the hypovolaemia and shock linked with the underlying cause. The mortality rate for complicated cases of ARDS approaches 90%.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE)

Venous thromboembolism is a major cause of complications and death after surgery or trauma and much of it is preventable. Venous blood is normally prevented from clotting within veins by a series of mechanisms that include local inhibition of the clotting cascade, prompt lysis of small clots that do form, and the flushing effect of a continuous flow of blood. In 1856, Virchow proposed in his ‘triad’ that venous thrombosis was caused by abnormalities in the vein wall (trauma, inflammation), alterations in blood flow (stasis) and changes in the blood (hypercoagulability); this explanation largely holds good today.

The normal antithrombotic balance within veins can be upset by local and/or systemic factors, resulting in thrombus formation in venous sinuses within calf muscles and sometimes primarily in pelvic veins. About 90% of deep vein thromboses (DVTs) start in the calf and about a quarter propagate proximally, usually within a week of presentation, to involve femoral and pelvic veins. Calf vein thrombosis alone is rarely symptomatic yet it predisposes strongly to proximal propagation, and 80% of symptomatic DVTs involve proximal veins. Calf vein thrombi themselves rarely cause substantial embolism but those in larger, more proximal vessels are likely to detach and migrate proximally to impact in pulmonary arteries as pulmonary emboli.

The main predisposing factors to venous thromboembolism (VTE) are summarised in Box 12.4, but thromboembolism can occur in healthy individuals without evident predisposing factors. A proportion will have a prothrombotic disorder and investigation for these should be performed later. Note that patients may have been ill and dehydrated at home for some time before hospital admission and venous thrombosis may have begun before admission.

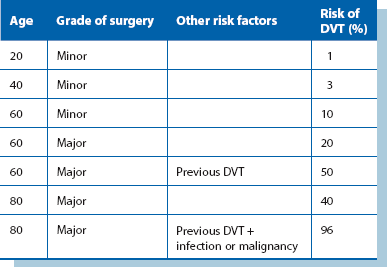

The risk of thromboembolism increases incrementally with the number and severity of local and systemic risk factors; this is neatly illustrated in Table 12.1. The impact of many predisposing factors can be minimised by prophylactic measures against venous thromboembolism in all hospitalised patients.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

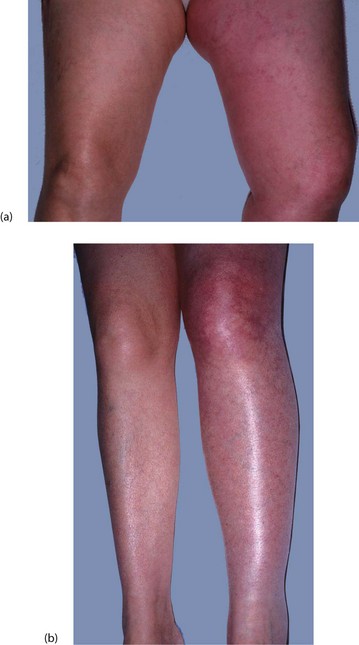

Lower limb deep vein thrombosis is often silent, with classic clinical features in only a quarter of cases. These include leg swelling, calf muscle tenderness and increased leg warmth; calf pain on passive foot dorsiflexion (Homans’ sign) is unreliable.

Iliofemoral vein occlusion tends to cause diffuse and sometimes massive swelling of the whole lower limb (see Fig. 12.6a). In addition, there may be tenderness over the femoral vein in the groin. In severe cases (rare nowadays), the limb becomes painful and white, and boggy with oedema; this is known as phlegmasia alba dolens (painful white leg). In more extreme cases, the limb becomes more painful and blue, with incipient venous infarction (phlegmasia caerulea dolens).

Asymptomatic DVTs have the same potential as symptomatic venous thromboses for causing both pulmonary embolism and long-term chronic venous insufficiency (see Ch. 43), thus emphasising the importance of prophylaxis for all patients at increased risk. To complicate the problem, as many as half the patients who develop swelling and pain in the calf after operation do not have deep vein thrombosis.

Diagnostic tests for DVT: Colour duplex ultrasound is now the standard technique for investigation of cases where DVT is suspected. In surgical patients, scanning is the preferred investigation as D-dimer blood tests can be misleading after an operation. Colour duplex allows scanning of all the major lower limb deep veins for blood flow and contained thrombus, and when the scan is normal, can reliably exclude the diagnosis.

Pulmonary embolism

The classic clinical picture of pulmonary embolism (PE) is sudden dyspnoea and cardiovascular collapse, followed by pleuritic chest pain, development of a pleural rub and haemoptysis. In hospital, this is often heralded by physical collapse whilst seated on the toilet. Ten percent of PEs are estimated to be fatal within the first hour. The electrocardiogram (ECG) may show evidence of right heart strain (S wave in lead I, Q wave and inverted T wave in leads III—′S1, Q3, T3′). This presentation, however, is uncommon and occurs only when 50% or more of the pulmonary arterial system is occluded. More extensive occlusion usually results in sudden death.

Small pulmonary emboli are common and are often ‘silent’, presenting as non-specific episodes of general deterioration, confusion, breathlessness or chest pain. Note that the patient suffering small embolic events is greatly predisposed to a massive or fatal embolus; it is essential to recognise the condition and to treat it seriously. The patient often has a tachycardia and low-grade fever but there are no diagnostic changes on ECG. Deterioration may be attributed to chest infection, atelectasis or cardiac failure unless pulmonary embolism is considered. There are sometimes more specific diagnostic symptoms of small emboli, including localised pleuritic chest pain and small haemoptyses in the form of blood-streaked sputum.

Venous thromboembolism is most common from about the fourth to the seventh day after major surgery but may present any time during the next month or so, sometimes after the patient has left hospital.

Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism (PE): In suspected pulmonary embolism, chest X-ray and ECG changes are non-specific and of little value. The choice of investigation depends on the level of clinical probability. Several clinical scoring schemes have been used to categorise patients to low (~10%), intermediate (~25%) or high (~80%) risk of pulmonary embolism. Categories are based on the sum of points allocated to predisposing factors (past history of venous thromboembolism, immobility, malignancy) and the presence of signs of DVT, tachycardia or an alternative diagnosis.

Blood tests for D-dimers have a high negative predictive value for pulmonary embolism (D-dimers are formed when cross-linked fibrin is lysed by plasmin), although levels are elevated anyway after operation and therefore misleading. The quickest and most reliable method of confirming the diagnosis is by dynamic spiral or multislice CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) using intravenous contrast (Fig. 12.7a). Where available, this has largely superseded radioisotope ventilation/perfusion scanning (V/Q scanning).

Fig. 12.7 Pulmonary embolism

(a) Thoracic CT pulmonary artery scan (CTPA) with intravenous contrast showing large emboli E in the pulmonary arteries. This is the investigation of choice where there is a high suspicion of PE. (b) Post-mortem specimen of lung from a patient who died of massive pulmonary embolism. Embolic material has been removed, but some remains in the pulmonary arteries E

Management of venous thromboembolism

For most patients, removing or lysing limb thrombus or pulmonary embolus is impracticable. The usual objective in managing thromboembolism is to halt the coagulation process by systemic anticoagulation. This prevents established thrombi from propagating and new thrombi from forming. Thrombus is then gradually removed by the normal body processes of lysis.

Most lower limb thrombi eventually become organised and firmly attached to the vein wall, posing no further risk of embolisation. Thrombus is later invaded by granulation tissue and veins eventually recanalise, restoring blood flow. In the process, valves are often destroyed, leading to chronic venous insufficiency (see Ch. 43), often many years later. After pulmonary embolism, if the patient survives the initial episode, emboli are efficiently removed by local thrombolysis, leaving little functional deficit.

For treatment, anticoagulation is initially achieved with therapeutic subcutaneous heparin. Heparin anticoagulation takes effect immediately and is continued for about 5 days, by which time acute symptoms have usually subsided. In the meantime, oral warfarin therapy (which takes several days to become fully effective) is begun. Warfarin is continued for 3–6 months, the period of highest risk of recurrent thromboembolism. It is likely that oral agents like rivaroxaban (see below) will replace both heparin and warfarin in the future for this purpose.

Untreated, about 50% of patients with proximal DVT or PE will have a further thromboembolic event within 3 months. Patients who suffer repeated thromboembolic episodes when taken off anticoagulation may need maintaining on warfarin or an alternative for life. For these patients, a filter may be placed in the inferior vena cava via a percutaneous route to trap emboli migrating from leg and pelvic veins towards the pulmonary arteries (see Ch. 5, p. 68).

In the rare case of sub-massive non-fatal pulmonary embolism with evidence of right ventricular dysfunction, surgical embolectomy may be appropriate. This is performed under cardiopulmonary bypass and is a major undertaking. An alternative is systemic thrombolytic therapy, but this has a high rate of serious bleeding and has largely been abandoned. However, the technique of manipulating a pulmonary artery catheter into the embolus and instilling high doses of local thrombolytic drugs or performing clot suction has occasionally been successfully employed.

Prevention of venous thromboembolism

The importance of general measures in preventing venous thrombosis needs to be emphasised. These include early postoperative mobilisation, adequate hydration and avoiding pressure on the calves. In addition, patients on oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives should ideally stop taking them (using replacement contraceptive methods) at least 6 weeks before major operations, as should patients on hormone replacement therapy (HRT). If these preparations are not to be stopped, consideration should be given to employing heparin prophylaxis for any operation.

For these and for any patients at risk (shown in Box 12.4), specific prophylactic measures should be taken to reduce the risk. Prophylactic measures include the following:

• Low-dose subcutaneous heparin—unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) both inhibit the activity of factor Xa indirectly by binding to circulating antithrombin III. Both types are as effective for preventing thromboembolism but LMWH has the advantage that it is given only once a day instead of two or three times. Low-dose heparin is currently the most effective method of reducing thromboembolism in at-risk patients. It has been shown to reduce the rate of postoperative DVT by 70% in general surgical, urological, gynaecological, orthopaedic and trauma patients. Similar reductions are achieved in pulmonary embolism rates. The beneficial intravascular antithrombotic effect is not due to anticoagulation, but arises from stimulation of platelet factor antithrombin III; there should be no detectable in vitro anticoagulant effect nor any significant effect on haemostasis during or after operation, although patients on low-dose heparin probably bleed about 10% more at major surgery

• A new class of orally active direct factor Xa inhibitor anticoagulants has become available. Rivaroxaban, an oxazolidinone derivative, has shown greater efficacy than enoxaparin (LMWH) in preventing thrombosis after hip and knee replacement, and with a similar safety profile, although the cost is higher. Maximum effect is reached after 4 hours and lasts 8–12 hours, tapering off afterwards so a once-daily dose of 10 mg is practicable. The drug does not inhibit thrombin (activated factor II), and has no effect on platelets. It has predictable activity across a wide range of age and body weight and has a flat dose response across a range of 5–40 mg. It enables predictable anticoagulation without need for dose adjustment or coagulation monitoring but is irreversible if haemorrhage occurs. The drug is approved widely for hip and knee replacement prophylaxis and further clinical trials are under way

• Calf compression devices—several pneumatic and electrical devices are available for intraoperative calf compression to simulate muscle pump activity. These are non-invasive and easily applied to all patients, even those at low risk, but their effectiveness is less than low-dose heparin

• Graduated compression ‘anti-embolism’ stockings—using these stockings is simple and widely practised. Provided they are correctly fitted, stockings offer a suitable level of prophylaxis for patients at low or moderate risk. The stockings must be worn during operation as well as during the early postoperative period

• Warfarin anticoagulation—warfarin is an orally active vitamin K antagonist that decreases hepatic synthesis of several coagulation factors. Warfarinisation is one of the best methods of prophylaxis for elective operations and is widely used in the Netherlands. It is considered impractical by many surgeons, not least because of the supposed risk of incidental and operative haemorrhage. In addition, providing an effective service requires a great deal of resources

Fluid and electrolyte disturbances

Fluid and electrolyte disturbances such as dehydration or fluid overload, hyponatraemia, hypokalaemia and hyperkalaemia frequently develop in the postoperative period. Fluid and electrolyte abnormalities are particularly common after major bowel surgery, especially if there have been massive fluid losses through vomiting, diarrhoea or sequestration in obstructed or adynamic bowel, or surgical complications. These problems are discussed in Chapter 2.

Antibiotic-associated colitis

Pathophysiology and clinical features

Colonic inflammation and other diarrhoeal disorders may be side-effects of almost any antibiotic treatment. The conditions are largely due to selective overgrowth of intestinal organisms which then produce toxins that cause the damage. The clinical picture ranges from a mild attack of diarrhoea to profuse, life-threatening, haemorrhagic colitis.

Antibiotic-associated colitis may develop suddenly or gradually and occasionally becomes chronic or relapsing. Surgical patients are most likely to be affected after operation. Clostridium difficile is responsible for many of these cases, and in severe form the full picture of pseudomembranous colitis may develop. This can take a particularly virulent form. Staphylococcal enterocolitis is less common.

Stool specimens should be examined by microscopy and culture and by measuring levels of Clostridium difficile toxin. Sigmoidoscopic inspection and biopsy of the rectum should also be performed. Treatment is based on the results of these tests. If Clostridium difficile infection is diagnosed, it is treated with oral metronidazole or, in resistant cases, with oral (non-absorbed) vancomycin and the patient must be isolated and barrier nursed (see Ch. 3).

Acute renal failure (insufficiency)

Acute renal failure is defined as the abrupt onset of oliguria or anuria, associated with a steep rise in blood urea concentration. This is caused by failure to excrete nitrogenous waste products. The usual cause is acute tubular necrosis, but acute renal failure is sometimes caused by nephrotoxins. These include the aminoglycoside antibiotics gentamicin and tobramycin, myoglobin (released in the crush syndrome) and the ‘hepatorenal syndrome’ associated with obstructive jaundice (see Table 18.2, p. 262). Acute renal failure is also a particular complication of abdominal aortic surgery, in which the renal arteries may become occluded by inadvertent damage or unrecognised embolism.

Pathophysiology

Renal tubules are acutely sensitive to a variety of metabolic insults, particularly hypoxia and certain toxins. Hypoxia readily occurs if renal perfusion falls substantially; the usual surgical cause is an episode of severe or prolonged hypotension. This may result from hypovolaemic shock (haemorrhage or dehydration), cardiovascular collapse (postoperative cardiac failure or myocardial infarction) or septic shock. In the last, endotoxic and cytokine-initiated renal cell damage is also an important factor. Pre-existing chronic renal disease increases a patient’s susceptibility to acute renal failure.

If the renal tubular insult is not overwhelming, tubular cell damage is confined to disruption of cellular metabolism rather than tissue necrosis. This is potentially reversible, provided the patient can be maintained in good general condition while tubular recovery takes place. The usual sequence of recovery is that poor urine output continues for a period (oliguric phase), followed by spontaneous diuresis of large volumes of unconcentrated urine consisting of unmodified glomerular filtrate (diuretic phase). Urinary concentrating power then slowly improves as tubules recover normal metabolic function. In contrast, when tubular damage is more extensive, the patient remains anuric or severely oliguric.

Prevention and management of acute renal failure

Acute renal failure is largely preventable by careful attention to preoperative assessment, fluid balance, and prevention and prompt management of hypotension and sepsis, as well as dose monitoring of potentially nephrotoxic drugs. When acute renal failure is mild, simple conservative measures such as fluid restriction may sustain the patient until tubular function recovers. When complete (oliguric) renal failure occurs, plasma urea, creatinine and potassium concentrations rise inexorably and the patient usually requires haemofiltration or renal dialysis. Fortunately, many of these patients recover renal function gradually over a few weeks or months and do not require permanent renal support.

Pressure sores

Elderly, debilitated and other bed-bound patients are extremely susceptible to pressure sores (‘bed sores’), particularly over bony prominences such as the sacrum and heels (see Figs 12.8 and 12.9). Pressure sores occur because the frequent spontaneous adjustment of position that normally occurs in bed is lost through obtunded sensation and immobility. Diminished protective pain response plays an essential part. Patients with diabetes may have a sensory neuropathy so they are unable to sense the damaging effects of prolonged pressure on a bony prominence. Tissue necrosis and any subsequent failure to heal result from a combination of factors including recurrent pressure ischaemia, poor tissue perfusion (from cardiac or peripheral vascular disease) and malnutrition. Note that patients who have experienced substantial weight loss and patients with relatively ischaemic lower limbs are at particular risk.

Prevention and management of pressure sores

Once established, pressure sores are difficult to eradicate so prevention must be given high priority in patients at risk. Relatively hard surfaces such as accident and emergency department trolleys and operating tables may initiate pressure sores in susceptible patients in less than an hour. Likewise, pressure sores can develop in a remarkably short time in a hospital bed, particularly if the patient is incontinent of urine or faeces. Prevention of pressure sores on the ward is mainly a nursing responsibility; indeed, the incidence of pressure sores is a good indicator of the quality of nursing care.

Prevention of pressure sores involves the following procedures:

• Special bed surfaces to spread the load—these include (in ascending order of cost and complexity) pressure-relieving foam mattresses, electric ripple mattresses, water beds, suspended net beds and sophisticated low pressure continuous airflow beds

• Relieving pressure on the heels—use of ankle rests while on the operating table, use of heel pads, orthopaedic foam gutters and ‘bean-bags’ on return to the ward

• Regular change of posture—for most patients, this involves encouragement to get out of bed, at least into a bedside chair, and to mobilise beyond the chair as much as possible. A bed-bound patient requires regular turning so that the same skin area is not subject to constant pressure

Treatment of established pressure sores is unsatisfactory unless causative factors can be eliminated. This is often impossible in the permanently disabled patient. Avoiding pressure is the mainstay of treatment, supplemented by local cleansing and dressings designed to remove necrotic tissue and control secondary infection. For a deep sacral sore, major plastic surgery involving a rotational buttock flap is occasionally justified.

Complications of operations involving bowel

These include delayed return of bowel function, mechanical bowel obstruction, anastomotic failure, intra-abdominal abscesses, peritonitis, bowel fistula and acute bowel ischaemia.

Delayed return of bowel function

Temporary interruption of peristalsis

Any abdominal operation may temporarily disrupt peristalsis. This is particularly true where the operation is for peritonitis, an abscess or intestinal obstruction, or if the operation involves extensive handling of the bowel. Operations involving the retroperitoneal area such as aortic surgery may also disrupt peristalsis, probably via a disturbance of parasympathetic activity. The problem mostly affects the small intestine. Patients may complain of nausea, anorexia and vomiting after oral fluids are reintroduced early in the postoperative period. This condition is often loosely described as ileus and is cited as a reason for gradual reintroduction of fluids, followed by solids after abdominal operations. However, if ileus is prolonged, another cause such as intestinal obstruction or an intraperitoneal collection of pus should be sought.

Adynamic bowel disorders

Occasionally, a much more prolonged and extensive form of functional adynamic bowel disorder occurs. This presents with vomiting and protracted intolerance to oral intake. Adynamic disorder must be distinguished from true mechanical obstruction, which may require reoperation. Adynamic bowel problems may be a response to local factors (e.g. bowel handling, a bowel wall haematoma or a collection of pus in contact with bowel) or to systemic abnormalities, particularly hypokalaemia.

Acute gastric dilatation: Occasionally, adynamic disorder involves the stomach, causing acute gastric dilatation and accumulation of large volumes of gastric and duodenal reflux secretions. The warning feature is when the patient suddenly vomits a large volume of fluid which may, even on the first occasion, result in fatal bronchial aspiration. Preventing acute gastric dilatation is the main reason nasogastric tubes are used after upper gastrointestinal surgery or after relief of mechanical bowel obstruction. If acute gastric dilatation is suspected, the abdomen should be examined for a succussion splash, and a nasogastric tube passed if the result is positive. If present, immediate nasogastric intubation is necessary; two or more litres of fluid that might otherwise be vomited and inhaled may need to be aspirated. Aspiration of gastric contents can cause mild or severe aspiration pneumonia (Mendelson’s syndrome).

‘Pseudo-obstruction’: Adynamic disorder involving the large bowel is conventionally but inaccurately described as pseudo-obstruction, as there is in fact no obstruction present. It may follow any abdominal operation, especially if the retroperitoneal area has been disturbed, as in nephrectomy or aortic surgery. Pseudo-obstruction is also a recognised complication of non-abdominal operations such as fractured neck of femur, especially in frail patients. It may even occur without operation as a complication of severe hypokalaemia, trauma involving the lower spine and retroperitoneal area, or anti-Parkinsonian and other drugs. The diagnosis can rapidly be made on an ‘instant’ unprepared water-soluble contrast enema by excluding mechanical causes of obstruction. Treatment involves identification and treatment of the underlying cause, together with supportive measures such as an indwelling flatus tube or deflation via colonoscopy until function returns.

Mechanical bowel obstruction

Early postoperative mechanical obstruction

Postoperative mechanical obstruction of the bowel is uncommon. It may be caused by a loop of bowel becoming twisted or trapped in a peritoneal defect, unwittingly created at open operation or laparoscopy. Fibrinous adhesions may also cause obstruction, and these usually develop about 1 week after operation. In both cases, the obstruction may be transient and settle with conservative measures (nasogastric aspiration and intravenous fluids), or may progress to full-scale intestinal obstruction requiring laparotomy. If tenderness and systemic signs of toxicity appear, reoperation becomes urgent to exclude strangulation. Obstruction occurring after gastrectomy or gastroenterostomy may be due to oedema of the mucosa surrounding the anastomosis; this usually settles eventually with conservative measures, although reoperation may be required.

Late postoperative mechanical obstruction

Fibrinous adhesions may organise and persist as broad fibrous adhesions between adjacent loops of bowel or as isolated fibrous bands traversing the peritoneal cavity. These are a common cause of an isolated episode of small bowel obstruction or even infarction. Adhesions may also cause recurrent bouts of bowel obstruction months or years after abdominal operations. Most episodes resolve spontaneously with conservative treatment, but failure of resolution or signs of strangulation (tenderness, toxaemia) necessitate laparotomy.

Adhesive obstruction has become less common since talc powder on surgical gloves was discontinued in the 1970s and possibly even less common since the declining use of starch on gloves. However, patients with recurrent intestinal obstruction due to adhesions present a serious surgical challenge. Each laparotomy becomes more difficult and hazardous for the patient. Therapeutic agents to prevent adhesions forming in the form of films are showing promise for high risk cases.

Anastomotic failure

Anastomotic leakage or breakdown is a major cause of postoperative morbidity after bowel surgery. Inadequate or delayed diagnosis and delayed surgical intervention may lead to multiple and cumulative complications including fistulae, sepsis, multi-organ dysfunction and failure, and death. There should be a low index of suspicion for leaks and a readiness to undertake reoperation if leakage is suspected.

Small anastomotic leaks are relatively common and lead to small localised abscesses which are walled off by surrounding gut and omentum. Small leaks manifest clinically by delayed recovery of bowel function resulting from local peristaltic dysfunction. Usually, the problem eventually settles with continued intravenous fluids and delayed reintroduction of oral intake. Reoperation, however, should be repeatedly considered if recovery is slow.

Major anastomotic breakdown results in generalised peritonitis, large abdominal abscesses, progressive sepsis and fistula formation.

Intra-abdominal abscesses

Abscess associated with bowel anastomosis

An anastomotic leak from any part of the bowel may be walled off by small bowel and omentum in a vigorous intraperitoneal response (see Fig. 12.10). This results in an abscess forming near the anastomosis. The patient will either be non-specifically unwell with delayed recovery, a swinging pyrexia and signs of local peritonitis, or more seriously ill with early signs of sepsis.

Early reoperation is usually necessary to drain the abscess and prevent continued peritoneal contamination. Where the anastomosis has broken down, both ends of the bowel should be brought out to form temporary stomas, since re-anastomosis will almost certainly fail. The bowel can often be rejoined once the local infection and metabolic disruption have resolved.

Other intra-abdominal abscesses

Intra-abdominal abscesses may also develop at sites remote from an anastomosis—for example, in the pelvis (pelvic abscess) or beneath the diaphragm (subphrenic abscess). These occur most often as a complication of treated peritonitis, particularly faecal peritonitis. They may also develop because of contamination of the operative site by faeces or other infected material, or by ‘tracking’ of an anastomotic abscess within the abdomen. Abscesses of this type usually produce a less severe illness than do those in direct communication with the bowel.

If an abscess is suspected, ultrasound or CT scanning may help to identify its location and guide needle aspiration or placement of a percutaneous drain if appropriate. Surgical exploration may, however, be necessary.

Peritonitis

Postoperative peritonitis usually results from a major anastomotic breakdown causing extensive peritoneal contamination. In other cases, the cause is perforation of obstructed or ischaemic bowel or perforation of an incidental peptic ulcer. The clinical picture may develop rapidly over a few hours or, if infection spreads from an intraperitoneal abscess, more gradually over a few days. The patient is systemically ill with severe, generalised abdominal pain; the abdomen is tender and rigid to palpation (see Ch. 19, p. 272 for more details). Note: elderly patients with peritonitis may have surprisingly little tenderness. Generalised peritonitis progresses to sepsis and multiple organ failure unless promptly treated.

The patient is resuscitated and commenced on intravenous antibiotics and then returned to theatre for laparotomy. The abdomen is explored, the underlying cause is treated and peritoneal toilet is carried out. Early and vigorous treatment will usually save the patient’s life.

Bowel fistula

Fistula formation as a complication of surgery usually results from an anastomotic leak or infarction of a segment of bowel. A local abscess first develops then discharges to the surface via the wound or along the track of an abdominal drain. Anastomotic breakdown is more likely when there is obstruction of bowel beyond the anastomosis; the fistulous tract then provides a means of drainage for obstructed bowel contents. With time, the drainage tract slowly becomes lined with epithelium from the bowel and the skin surface and the fistula becomes permanent. Occasionally a fistula develops in a patient after an operation for bowel cancer. In this case the fistula may become lined with malignant cells. Proximal small bowel fistulas result in loss of large volumes of intestinal secretions containing digestive enzymes. This rapidly leads to dehydration and major electrolyte disturbances and usually causes gross intra-abdominal inflammation and skin destruction. The more proximal the origin of the fistula, the greater the volume of fluid and electrolyte loss and the more damaging its consequences.

The general state of the patient with a fistula depends on the extent of intra-abdominal infection. If this is minimal and there is no distal obstruction, the fistula usually closes spontaneously within weeks or months, provided the patient can be sustained in the interim. Proximal small bowel fistulas require total bowel rest (i.e. nil by mouth and a nasogastric tube) with full parenteral fluid replacement and nutrition. Somatostatin analogues may be given to substantially reduce the volume of secretion into the small bowel. Distal small bowel or large bowel fistulas may be managed with enteral feeding using low-residue elemental or semi-elemental fluid diets. These are often given via a fine-bore nasogastric tube.

When a fistula is associated with intra-abdominal infection, the patient is desperately ill, septic and hypercatabolic. These patients need intensive care management and reoperation. Laparotomy is required to bring the disrupted bowel ends to the surface as stomas and to drain the gross foci of infection; further laparotomies, even daily, may still be required before the intra-abdominal infection is brought under control. Mortality from these complicated fistulas is high.

Acute bowel ischaemia

Acute bowel ischaemia is an uncommon postoperative complication, usually occurring after abdominal aortic surgery. Infarction of the sigmoid colon follows inferior mesenteric artery ligation (usually a necessary part of the operation) if the collateral blood supply is compromised by obliterative atherosclerosis of the remaining mesenteric arteries. Fortunately, this is rare. The patient has usually progressed well at first then deteriorates unexpectedly several days after operation, often passing fresh blood per rectum. If untreated at this stage, the patient later collapses with peritonitis due to colonic necrosis and perforation.

Clinical signs of acute bowel ischaemia are non-specific, but often the degree of pain and collapse is out of proportion to the minimal abdominal signs. Plain abdominal X-ray may show ‘thumb printing’ of the affected bowel or the characteristic appearance of gas in the bowel wall. If acute bowel ischaemia is suspected, laparotomy must usually be performed urgently as perforation will soon occur and is nearly always fatal. Even with timely surgery, the prognosis is bleak.