Chapter 15 Complications of Radiofrequency Rhizotomy for Facet Syndrome

Appropriate Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mentored subspecialty training in interventional pain management is vital to ensure patient-centered care.

Appropriate Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education mentored subspecialty training in interventional pain management is vital to ensure patient-centered care. Common complications, regardless of the RF modality used, include transient increased localized pain and usually self-limiting neuritis.

Common complications, regardless of the RF modality used, include transient increased localized pain and usually self-limiting neuritis. Infectious complications are less common than in the diagnostic or therapeutic steroid injections, potentially related to the thermal injury created.

Infectious complications are less common than in the diagnostic or therapeutic steroid injections, potentially related to the thermal injury created.Introduction

Rhizotomy techniques have revolutionized treatment for many pain states and are commonly used to treat facetogenic pain after appropriate controlled diagnostic injections. Relatively recent reviews approximated lumbar, thoracic, and cervical zygapophyseal pain to be 31%, 40%, and 39%, respectively, using dual controlled diagnostic injections (Table 15-1).1–3

Table 15-1 Prevalence and Diagnostic Accuracy of Zygapophyseal Joint Pain

| Prevalence (%)* | Diagnostic Accuracy: False Positive Rate* (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical | 39 (23–45) | 45 (37–52) |

| Thoracic | 40 (33–48) | 42 (33–51) |

| Lumbar | 31 (28–33) | 30 (27–33) |

* 95% confidence interval using 80% pain reduction.

Data from Manchukonda R, Manchikanti KN, Cash KA, et al: Facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain: An evaluation of prevalence and false-positive rate of diagnostic blocks, J Spinal Disord Tech 20:539-545, 2007.

Facetogenic injections are required to make diagnosis because no physical, historical, or radiographic examination feature are unreliable,4 but attempts at noninvasive diagnostic strategies are ongoing.5 Interestingly, later Cohen et al6 looked at the cost effectiveness of one, two, or no controlled diagnostic injection before facet radiofrequency (RF) treatment and summarized that from a cost analysis perspective, proceeding to RF denervation before diagnostic injection was superior, and although efficacy determination was not a study endpoint, the treatment outcome related to duration and magnitude of pain relief was greater for the dual diagnostic blockade group.

Regardless of the diagnostic treatment algorithm used, RF techniques are a safe and effective means to treat zygapophyseal pain.7 However, RF techniques are not created equal, and an understanding of the different modalities is crucial to understand the potential pitfalls and safety concerns.

Background

Thermal (Traditional, Conventional, or Continuous) Radiofrequency

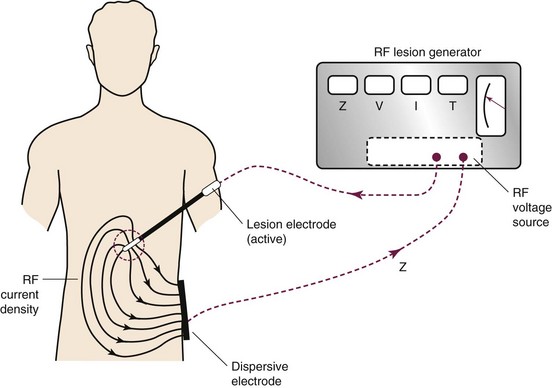

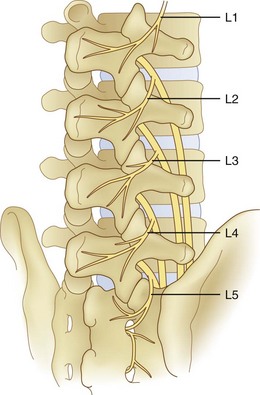

Thermal RF was first introduced in the 1930s. The thermal lesion is created by the introduction of an insulated electrode with an active tip of (2 to 10 mm), a dispersal plate, and a power source to complete the circuit (Fig. 15-1).

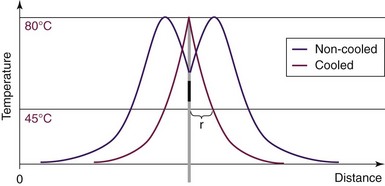

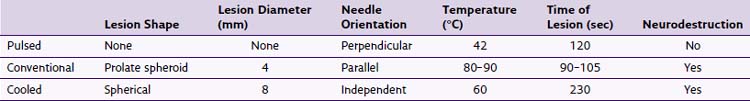

High-frequency electrical current is then applied adjacent to the structure of the nerve that is intended to ablate; such current leads to ionic oscillation and frictional dissipation of the ions and electrolytes, which produce heat. The heat produced is directly related to the amplitude of the applied current and electrode size and indirectly related to distance from the electrode. The tip of the electrode measures the tissue temperature. Larger lesions are created by increased temperature, size of the electrode, and duration of applied current. Monopolar lesioning is performed when one electrode is used. Bipolar lesioning occurs when two electrodes are used in close proximity to one another. Laboratory evidence suggests that cellular damage occurs at temperatures of 60° to 65°C. As suggested by the aforementioned isotherm mapping from the electrode tip, 80° to 85°C is required at the needle tip, where the desired 60° to 65°C is achieved in the surrounding tissue, producing a prolate ovoid-shaped lesion (Fig. 15-2). Therefore, because the lesion created does not extend distal to the electrode, proper electrode position is parallel to the target nerve.

Fig. 15-2 Traditional thermal radiofrequency lesion.

(Courtesy of Dr. Nagy Mekhail, MD, PhD, Cleveland Clinic.)

The neurotomy created by the thermal technique is dependent on proximity to the targeted nerve, size of electrode, the temperature (or amplitude of current) applied, and the duration of lesioning. When applied immediately adjacent to the dorsal root ganglion, temperatures of 45°, 55°, 65°, 75°, and 85°C produce complete destruction of unmyelinated and near complete destruction of myelinated fibers.8

Pulsed Radiofrequency

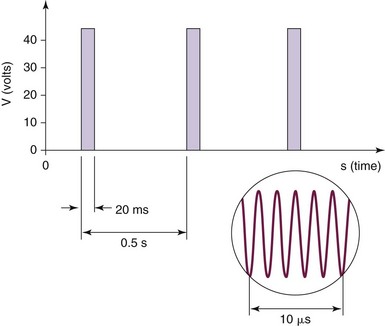

Pulsed RF was first introduced in 1998, and the aforementioned circuit is used. Interestingly, there is no creation of a histologic lesion, and no nerve degeneration occurs (no Wallerian degeneration). The treatment is produced by providing current of 50,000 Hz in 20-msec pulses at a frequency of 2 per second. The temperature is maintained to be below 42°C or 45 V (Fig. 15-3). The greatest current density delivered is at the tip of the electrode; so ideal placement is perpendicular to the target nerve.

The mechanism of the therapeutic treatment is less clear compared with thermal RF and is surrounded by controversy. The mechanism appears to be independent of temperature and is neuromodulatory in nature,9–12 and one resounding conclusion can be made: There is no histologically detected cellular destruction.

Cooled Radiofrequency

Cooled RF is a misnomer. The neurotomy produced is secondary to thermal destruction; however, the cooled RF uses a lower temperature than traditional thermal RF lesioning (Fig. 15-4). The traditional RF lesion size is limited by the charring of tissues around the electrode as the temperature of tissues rises. On the other hand, cooled RF maintains the temperature adjacent to the electrode at a desired lower level to prevent tissue charring, hence allowing the lesion to expand and increase in size.13

The resultant lesion is spherical in shape (Fig. 15-5). The radius of the spherical lesion equals the length of the active tip of the electrode. Simply, the tip of the electrode is the center of the spherical lesion. Therefore, the cooled RF lesion is eight times by volume the thermal RF lesion for the same length electrode tip.13 Whereas the spherical lesion projects distally from the electrode, conventional thermal RF produces a prolate ovoid parallel to the active tip of the needle (see Fig. 15-2) with little or no projection distally. Consequently, unlike thermal RF, which requires parallel electrode placement adjacent to the target nerve, cooled RF lesions are independent of electrode orientation.14

Summarily, and as described, important differences regarding lesion size, electrode placement, and neural destruction need to be noted (Table 15-2).

Selected Complications

Despite routine use, complications, similar to those associated with the diagnostic or therapeutic zygapophyseal injections, are rare. See Chapter 14 for further details. Other modalities to produce lesions to treat facetogenic pain include alcohol, phenol, laser, and kryoneurolysis.15–19 This chapter focuses on complications specific to RF neurotomy, and none will be discussed further. Theoretical risks regarding RF neurotomy are listed in Box 15-1.

Postprocedure Pain and Neuritis

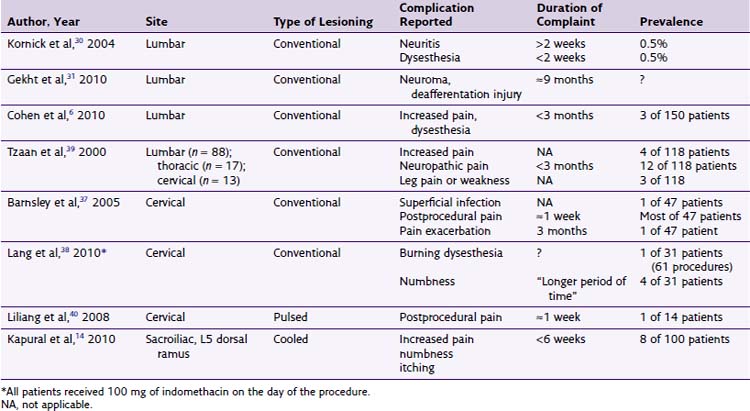

There is sparse literature describing the complications associated with RF treatments (pulsed, conventional, or cooled) for facetogenic pain.7,20–29 No cooled RF of the lumbar median branches has been formally reported, although some advocate its use. Kornick et al30 performed a retrospective review over a 5-year period at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, in a total of 92 patients receiving 616 RF lesions (80°C for 90 seconds) during 116 separate procedures. Of the 616 lesions, six complications were noted—three cases of localized pain at the RF sites lasting more than 2 weeks and three cases of neuritic pain lasting less than 2 weeks (Table 15-3). No motor, sensory, vascular, or infectious complications were noted.30 A case report of neuroma formation after multiple RF ablation procedures has been described. It was successfully treated with an open minimally invasive medial branch neurectomy.31

Dobrogowsi et al32 investigated strategies to reduce the inflammatory pain associated with the lesioning. In a randomized prospective trial, patients were randomized to intraoperative methylprednisolone (10 mg), pentoxifylline (10 mg), or saline (1 mL). No “severe local tenderness” was reported in either the methylprednisolone group or pentoxifylline group, with minor tenderness resolving within 1 month, compared with the saline group, which had four of 15 patients with severe pain at 1 week and one patient for longer than 1 month. Other authors33 report that 3-day dosage of diclofenac to be effective in reducing procedural pain after conventional RF neurotomy of lumbar median branches (Fig. 15-6).

Burn Injuries

Burn injuries have been reported early in literature and were the result of equipment malfunction, insulation breaks within the electrodes, a unipolar electrosurgical unit return plate, or unknown causes.34–36 Whereas operating room power supplies are ungrounded systems, office buildings are typically grounded systems. This difference dramatically impacts the chance of burn injury (or macroshock) to the patient because isolated systems are more difficult to deliver aberrant current. Furthermore, burn severity is related to current density, either greater the current or the smaller the area applied.

Infectious Complications

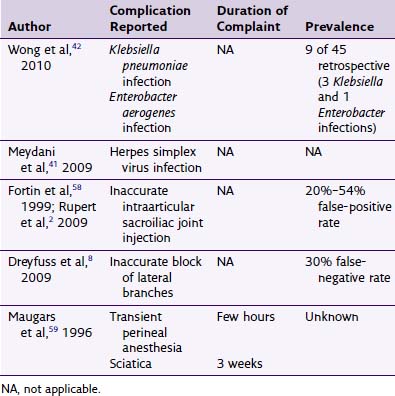

There very few reported infectious complications. Barnsley37 reported a superficial infection after cervical conventional RF that resolved after enteral antibiotics were administered.38 Furthermore, some contend that the inherent heating of the tissue during the thermal lesioning may provide some means of bacteriocidal effect.6

Needle Placement

Proper needle placement during RF denervation is essential, as described in Chapter 7. Improper placement can lead to thermal destruction of nontargeted tissues, including the ventral rami. Although a serious concern, with proper motor testing before lesioning with an increase of stimulation to at least 2 V at 2 Hz, this complication should be avoided.

1 Datta S, Lee M, Falco FJ, et al. Systematic assessment of diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic utility of lumbar facet joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2009;12:437-460.

2 Alturi S, Datta S, Falco FJE, Lee M. Systematic review of diagnostic utility and therapeutic effectiveness of thoracic facet joint interventions. Pain Physician. 2008;11:611-629.

3 Manchukonda R, Manchikanti KN, Cash KA, et al. Facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain: An evaluation of prevalence and false-positive rate of diagnostic blocks. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:539-545.

4 Cohen SP, Raja SN. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of Lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:591-614.

5 McDonald M, Cooper R, Wang MY. Use of Computed tomography-single-photon emission computed tomography fusion for diagnosing painful facet arthropathy. Technical note. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22(1):E2.

6 Cohen SP, Williams KA, Kurihara C, et al. Multicenter, randomized comparative cost-effectiveness study comparing 0, 1 and 2 diagnostic medial branch (facet joint nerve) block treatment paradigms before lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:395-405.

7 Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, et al. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Spine. 2000;25:1270-1277.

8 Van Boxen K, van Eerd M, Brinkhuize T, et al. Radiofrequency and pulsed radiofrequency treatment of chronic pain syndromes: the available evidence. Pain Med. 2008;8:385-393.

9 Tun K, Cemil B, Gurcay AG, et al. Ultrastructural evaluation of pulsed radiofrequency and conventional radiofrequency in rat sciatic nerve. Surg Neuro. 2009;72:496-501.

10 Molina JAL, Rivera MJ, Trujillo M, Berjano EJ. Thermal modeling for pulsed radiofrequency ablation: analytical study based on hyperbolic heat conduction. Med Phys. 2009;36:1112.

11 Cahana A, Van Zundert J, Macrea L, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency: current clinical and biological literature available. Pain Med. 2006;7:411-423.

12 Bogduck N. Position papers: pulsed radiofrequency. Pain Med. 2008;7:396-407.

13 Kapural L, Mekhail N, Hick D, et al. Histological changes and temperature distribution studies of a novel bipolar radiofrequency heating system in degenerated and nondegenerated human cadaver lumbar discs. Pain Med. 2008;9:68-75.

14 Kapural L, Stojanovic M, Bensitel T, Zovkic P. Cooled radiofrequency of L5 dorsal ramus for RF denervation of the sacroiliac joint: technical report. Pain Med. 2010;11:53-57.

15 Andres RH, Graupner T, Barlocher CB, et al. Laser guided lumbar medial branch kryorhizotomy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:341-345.

16 Li G, Patil C, Adler JR, et al. CyberKnife rhizotomy for facetogenic back pain: a pilot study. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(6):E2.

17 Iwatsuki K, Yoshimine T, Awazu K. Alternative denervation using laser irradiation in lumbar facet syndrome. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:225-229.

18 Barlocher CB, Krauss JK, Seiler RW. Kryorhizotomy: an alternative technique for lumbar medial branch rhizotomy in lumbar facet syndrome. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:14-20.

19 Staender M, Maerz U, Tonn JC, Steude U. Computerized tomography-guided kryorhizotomy in 76 patients with lumbar facet joint syndrome. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:444-449.

20 North RB, Han M, Zahurak M, et al. Radiofrequency lumbar facet denervation: analysis of prognostic factors. Pain. 1994;57:77-83.

21 Gallagher J, Petriccione Di Vadi PL, Wedley JR, et al. Radiofrequency facet joint denervation in the treatment of low back pain: a prospective controlled double-blind study to assess its efficacy. Pain Clin. 1994;7:193-198.

22 Leclaire R, Fortin L, Lambert R, et al. Radiofrequency facet joint denervation in the treatment of low back pain. Spine. 2001;26:1411-1417.

23 Slappendel R, Crul BJ, Braak GJ, et al. The efficacy of radiofrequency lesioning of the cervical spinal dorsal root ganglion in a double blinded randomized study: no difference between 40 degrees C and 67 degrees C treatments. Pain. 1997;73:159-163.

24 Lord S, Barnsley L, Wallis B, et al. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

25 Mikeladze G, Espinal R, Finnegan R, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency application in treatment of chronic zygapophyseal joint pain. Spine J. 2003;3:360-362.

26 Cho J, Park YG, Chung SS. Percutaneous radiofrequency lumbar facet rhizotomy in mechanical low back pain syndrome. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1997;68:212-217.

27 Royal MA, Bhakta B, Gunyea I, et al. Radiofrequency neurolysis for facet arthropathy: a retrospective case series and review of the literature. Pain Pract. 2002;2(1):47-52.

28 Kroll HR, Kim D, Danic MJ, et al. A randomized, double-blind, prospective study comparing the efficacy of continuous versus pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of lumbar facet syndrome. J Clin Anesth. 2008;20:534-537.

29 Mancikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJE, et al. Comparative effectiveness of a one-year follow-up of thoracic medial branch blocks in management of chronic thoracic pain: a randomized, double-blind active controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2010;13:535-548.

30 Kornick C, Kramarich SS, Lamer TJ, Todd Sitzman B. Complications of lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Spine. 2004;29:1352-1354.

31 Gehkt G, Nottmeier EW, Lamer TJ. Painful medial branch neuroma treated with minimally invasive median branch neurectomy. Pain Med. 2010;11:1179-1182.

32 Dobrogowski J, Wrzosek A, Wordliczek J. Radiofrequency denervation with or without addition of pentoxifylline or methylprednisolone for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:475-480.

33 Ma K, Yiqun M, Wang W, et al. Efficacy of diclofenac sodium in pain relief after conventional radiofrequency denervation for chronic facet joint pain: a double blind randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2010;12(1):27-35.

34 Shealy CN. Percutaneous radiofrequency denervation for spinal facets: treatment for chronic back pain and sciatica. J Neurosurg. 1975;43:448-451.

35 Katz SS, Savitz MH. Percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy of the lumbar facets. Mount Sinai J Med. 1986;53:523-525.

36 Ogsbury JS, Simon RH, Lehman RAW. Facet “denervation” in the treatment of low back pain. Pain. 1977;3:257-263.

37 Barnsley L. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain: outcomes in a series of consecutive patients. Pain Med. 2005;6(4):282-286.

38 Lang JK, Buchfelder M. Radiofrequency Neurotomy for headache stemming from the zygapophysial joints C2/3 and C3/4. Cen Eur Neurosurg. 2010;71:75-79.

39 Tzaan WC, Tasker RR. Percutaneous radiofrequency facet rhizotomy-experience with 118 procedures and reappraisal of its value. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27:125-130.

40 Liliang PC, Lu K, Hsieh CH, et al. Pulsed radiofrequency of cervical medial branches for treatment of whiplash-related cervical zygapophyseal joint pain. Surg Neurol. 2008;70(suppl 1):50-55.