125 Complications of Gynecologic Procedures, Abortion, and Assisted Reproductive Technology

• Complications with the highest morbidity and mortality are severe hemorrhage, serious infection, damage to intraabdominal structures, and pulmonary embolism.

• Complications seen in the emergency department are usually delayed in presentation, and often difficult to diagnose due to insidious onset, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality and a higher risk for litigation (i.e., ureteral injuries) High suspicion must be maintained.

• Emergency department bedside ultrasonography can provide rapid, early imaging for the evaluation of postprocedural patients, particularly unstable ones.

• Abortion is one of the most common procedures in the United States and overall has very low serious complication rates.

• Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is a potentially fatal complication of assisted reproduction in a generally healthy young woman. With no cure, early recognition, aggressive intervention, and close monitoring are key.

More than 146,000 cycles of ART were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from 441 sites in the year 2009. In addition, approximately 600,000 hysterectomies are performed annually, which ranks it behind cesarean section as the most common major surgery in women of reproductive age.2

Complications of Gynecologic Procedures

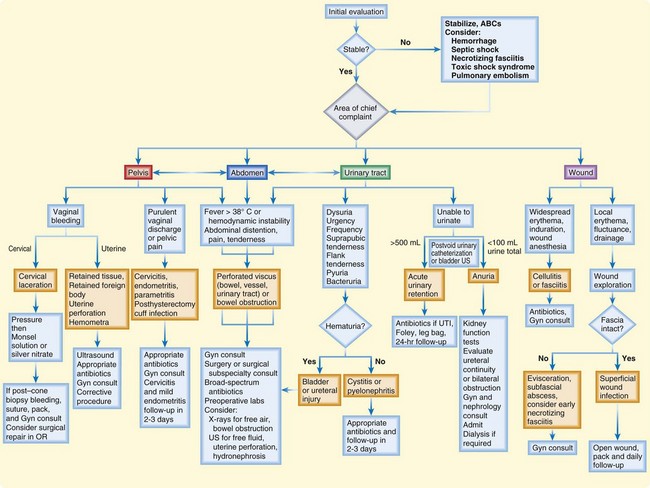

This section focuses on complications particular to gynecologic procedures that one might encounter in the ED setting and their evaluation and management (Fig. 125.1). Many complications of gynecologic procedures may go unrecognized before discharge, only to be seen later in the ED (Box 125.1). Box 125.2 lists the typical timing of these complications.

Fig. 125.1 Suggested algorithm for the evaluation and treatment of postoperative gynecologic patients.

Box 125.2 Complications of Gynecologic Procedures by Estimated Time Line

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

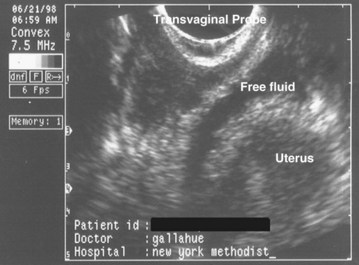

For patients with complications after a gynecologic procedure, bedside ultrasonography (US) in the hands of a skillful operator can provide rapid recognition of intraabdominal and intrapelvic pathology. Possible ultrasonographic findings include free fluid heralding leakage from a perforated vessel, urinary tract, or viscus (Fig. 125.2); hydronephrosis as a result of ureteral obstruction; a full bladder secondary to urinary retention; fluid collections; and intrauterine contents. US can also be used to guide paracentesis for definitive fluid diagnosis or for the drainage of subcutaneous abscesses. It is important to remember that sensitivity and accuracy are very dependent on the user and interpreter and that anatomy, habitus, and elements such as bowel gas can greatly interfere with adequate imaging. US is a poor modality for evaluating the bowel or retroperitoneal space.

Fig. 125.2 Transvaginal ultrasound image showing free fluid in the cul-de-sac consistent with hemorrhage.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Differential Diagnosis: Complications of Gynecologic Procedures

Abnormal Symptoms or Vital Signs?

Vaginal Bleeding—Is It Cervical or Uterine in Origin?

Unable to Urinate?

Wound Redness and Drainage?

Localized? If so, check the fascia; if it is intact, treat as a superficial wound infection with packing and close follow-up. If the fascia is not intact, consider a subfascial abscess, early necrotizing fasciitis, or hernia or evisceration; make sure that it is not an incarcerated hernia; gynecology consultation and possible surgical evaluation are required.

Widespread? Consider cellulitis or fasciitis; administer antibiotics and hospitalize the patient. If only mild cellulitis is present, oral antibiotics, very close follow-up, and explicit return instructions are required (consider priming with first dose of intravenous antibiotics).

CT, Computed tomography; ED, emergency department; US, ultrasound; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Urinary Tract Injury

The incidence of urinary tract injury in gynecologic surgery is between 0.33% and 4.8%. The great majority (80%) of these injuries involve the bladder. Ureteral injuries occur in just 0.3% to 1.0% of cases, but unilateral injury is discovered postoperatively in the majority of cases.3 This delayed recognition leads to increased morbidity. As a result, ureteral injury has become the leading cause of legal action against gynecologic surgeons.

Months to years after the procedure, watery drainage from the vagina heralds an ureterovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula, whereas watery wound drainage suggests a ureterocutaneous or vesicocutaneous fistula (Table 125.1).

Table 125.1 Clinical Findings and Bedside Diagnosis of Pelvic Fistulas

| TYPE OF FISTULA | FINDINGS | BEDSIDE DIAGNOSIS |

|---|---|---|

| Ureterovaginal | Copious, watery vaginal discharge; multiple urinary tract infections |

Place a tampon in the vagina and administer oral activated charcoal. A stained tampon is diagnostic.

Higher colonic lesions may be diagnosed by oral administration of activated charcoal.

To differentiate from ureterocutaneous fistulas, insert a urinary catheter, instill methylene blue via the catheter and clamp it off, wait

hour, and then drain the bladder until clear and perform the test described below.

hour, and then drain the bladder until clear and perform the test described below.Wound and Abdominal Wall Infections

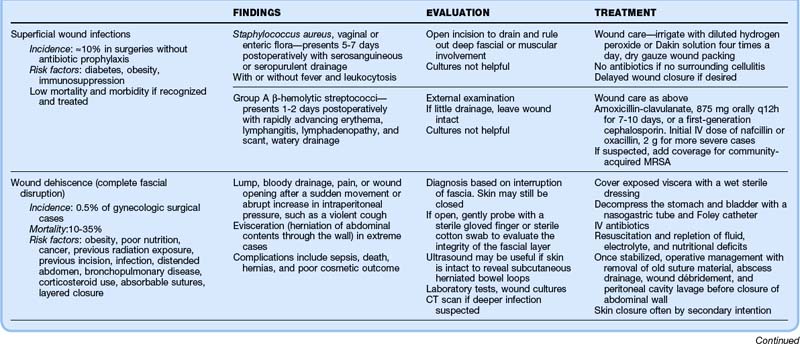

Thorough evaluation requires opening the wound for drainage and examination for deep fascial or muscular involvement. Superficial wound infections can be managed without antibiotics by meticulous wound care, irrigation with diluted hydrogen peroxide or Dakin solution four times per day, and dry gauze packing. Delayed wound closure can be performed if necessary. Table 125.2 details the clinical findings, evaluation, and treatment of wound infections, dehiscence, and necrotizing fasciitis.

Complications Specific to Laparoscopy

Laparoscopic procedures are characterized by more rapid recovery and lower complication rates than seen with open surgical procedures. However, unique complications are associated with needle or trocar insertion, induced pneumoperitoneum, and extensive use of electrocautery4,5 (Box 125.3). Most catastrophic complications are recognized intraoperatively. Management in the ED in the first month postoperatively is usually for wound complaints or symptoms caused by injury to the bowel, bladder, or ureters. Remote complications include hernias.

Box 125.3 Most Threatening and Most Common Complications of Laparoscopy Seen Postoperatively

Complications of Uterine Fibroid Embolization

A relatively new procedure, uterine fibroid embolization has been rapidly gaining in popularity in the United States, from 50 cases performed in 1996 to now more than 100,000 worldwide. Early results show a success rate of about 90% and a complication rate of about 5% by American College of Gynecology criteria.6 Patients have a shorter hospitalization and return to activities sooner but have a higher rate of treatment failure and delayed rehospitalization than patients undergoing surgery.

Occasionally, the embolization goes awry (“nontarget embolization”), and severe tissue ischemia and necrosis occur in undesirable areas such as the buttock, labia, and vaginal vault. Box 125.4 lists the most common and most life-threatening complications.

Box 125.4 Most Threatening and Most Common Complications of Uterine Fibroid Embolization

Bleeding after Cervical Procedures

Cervical cancer used to be the top cancer killer of women in the United States. Even though numbers have declined over the past few decades because of the emphasis on regular Papanicolaou tests, in 2007 cervical cancer was diagnosed in 12,280 women, and 4021 died of the disease.7 Cervical procedures such as cervical conization (laser conization, cold knife conization, loop electrosurgical excision), colposcopy, and cryotherapy are used for the diagnosis and treatment of early cervical neoplasia.

Treatment

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Patients with Complications of Gynecologic Procedures

Physical Examination

Does the patient look ill? pale? febrile? uncomfortable?

Abdominal examination—Distention, soft, tender, peritoneal signs

Speculum examination—Vaginal discharge, bleeding, color, quantity

Bimanual examination—Uterine and ovarian size and texture, tenderness

Wound evaluation—Is there discharge? Erythema? Tenderness? Is it intact at all layers?

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

After a Gynecologic Procedure

Explain the normal postoperative course to the patient.

If the patient is not being admitted, schedule follow-up with the patient’s physician in the next 1 to 3 days.

If antibiotics are prescribed, instruct the patient to complete the entire course of therapy as indicated.

Tell the patient to call her physician or return to the emergency department if she has:

Postabortion Complications

Epidemiology

Since becoming legalized nationwide in 1973, termination of pregnancy has become among the most frequently performed operative procedures in the United States, with more than 1 million performed yearly. A total of 1.2 million cases were reported in 2008.8 An estimated half of all pregnancies are unplanned, and 40% of unintended pregnancies are terminated. In fact, each year approximately 3% of all women of childbearing age have abortions, thus accounting for almost one fourth of all pregnancies. Most abortions are performed during the first trimester—62% within the first 8 weeks and 95% within the first 16 weeks.9 Overall complication rates are low, ranging from 1% to 5% of cases, and associated maternal mortality is extremely rare. Death is infrequent, with seven occurring after the almost 1 million legal abortions reported in the United States in 2005.8 In fact, for every gestational age, mortality is lower with abortion than with pregnancy and childbirth.10

Medical abortion has a success rate of 80% to 97% (higher for gestations <50 days); 2% to 5% of patients with failed abortions require subsequent surgical abortion, with a 5% to 10% rate of incomplete evacuation of products of conception.11,12

Pathophysiology

Surgical Abortion

Dilation plus curettage is the most frequently used abortion method in the United States (>90% of abortions).8 The cervix is dilated and the uterine contents scraped out with a curette or aspirated via vacuum extraction. In the first trimester the overall risk profile is very low (0.1% to 0.3%) and even lower with regional anesthesia. However, the complication rate does increase with increasing gestational age.

Dilation plus evacuation is performed to terminate pregnancies more than 16 weeks of gestation. Dilation is achieved via osmotic dilators (i.e., laminaria) or vaginally administered prostaglandins, as opposed to instrumentation, and the uterine contents are removed with forceps or vacuum. This technique is also used for the management of spontaneous abortion, retained products of conception, intrauterine fetal demise, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Its application depends on uterine volume, age of gestation, and operator experience.13

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

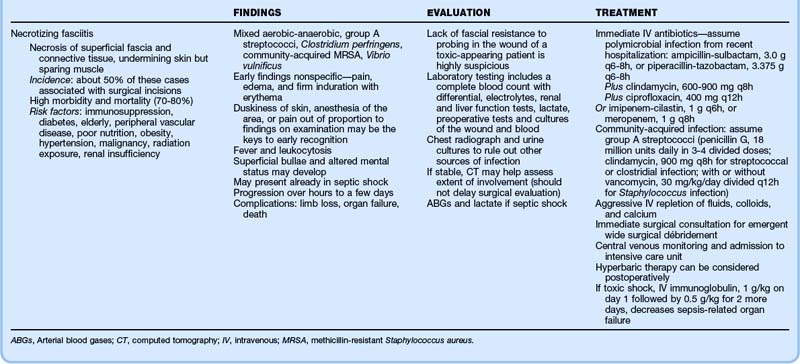

General complications of abortion include retained pregnancy, hemorrhage, infection, and incomplete evacuation (Table 125.3); the most threatening and most common complications of abortion are listed in Box 125.5.

Complications of Surgical Abortion

Surgical abortion carries the risks associated with anesthesia, in addition to those related to the procedure. Complications categorized as immediate, delayed, and long term are listed in Box 125.6.

Hemorrhage

Uterine perforation carries a high risk for concomitant damage to the intraperitoneal structures and severe hemorrhage. Delayed manifestation is not uncommon because fundal perforations (accounting for two thirds of all perforations) have scant bleeding. Lateral perforations may have heavy bleeding hidden in the broad ligament, and a lacerated uterine artery may initially spasm. The signs and symptoms depend on the site of perforation (Table 125.4). Uterine perforation related to surgical abortion or uterine rupture from medical abortion must be considered in patients with vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain.

| SITE | SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

| Any site |

Treatment

Uterine perforation related to surgical abortion and uterine rupture from medical abortion are surgical emergencies, so gynecology must be involved early. Laparotomy or laparoscopy to examine the abdominal contents is usually indicated, although small perforations may be managed expectantly with consideration of antibiotic treatment. In the presence of rapid bleeding, insertion of a Foley catheter into the uterus and inflation of the balloon with 60 mL of saline can serve as a temporizing tamponade (Table 125.5).

Table 125.5 Treatment of Postabortion Hemorrhage Without Perforation

| CAUSE OF HEMORRHAGE | TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| Uterine atony |

IM, Intramuscularly; IV, intravenous; NS, normal saline.

Postabortion Infection

Treatment

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Postabortion Instructions

Instruct the patient about the natural course of recovery, in particular how much bleeding and pain can be anticipated and when to be concerned.

If antibiotics are prescribed, the patient should complete the entire course as indicated.

Inquire whether the patient wishes to use contraception. Also clarify that only barrier contraception protects against sexually transmitted diseases as well.

Tell the patient to call her physician or return to the emergency department if she has

Complications of Assisted Reproductive Technology

Epidemiology

On July 25, 1978, Louise Brown, the original “test tube baby,” was born in England. Conceived by in vitro fertilization, her birth was a landmark in the history of ART. Four years later, the first child conceived by ART in the United States was born. In 2009, 146,244 ART procedures were reported by 441 sites in the United States, resulting in more than 60,000 babies.1 and it is estimated that more than 1% of children conceived worldwide can be attributed to ART each year.

Despite the growing frequency of ART, however, published data on complications are limited. What does exist focuses primarily on outcomes of the pregnancy (multiple-birth gestations, low-birth-weight babies, cesarean sections, and preterm delivery), as well as long-term effects on women and the resultant children.14 These complications are dealt with only indirectly in the ED.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

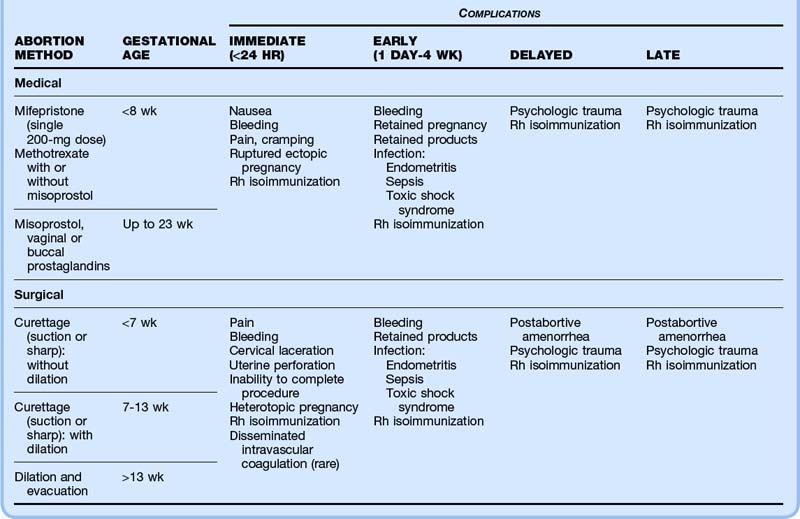

Major complications of ART likely to be encountered in the ED include ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), ectopic or heterotopic pregnancy, miscarriage, ovarian torsion, ovarian rupture, thromboembolism, and postprocedural complications (Table 125.6 and Box 125.7).

Box 125.7 Most Threatening and Most Common Complications of Assisted Reproductive Technology

Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome

Epidemiology

OHSS is the most feared complication of ovulatory stimulation. Severe OHSS is life-threatening and occurs in an estimated 0.5% to 5% of ART cycles. It also occurs occasionally in spontaneous pregnancy. The estimated mortality rate is 1 in 400,000 to 500,000 patients.15

Pathophysiology

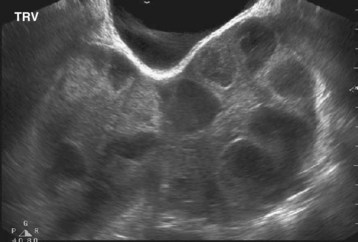

Risk factors include young age, low body mass index, use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and exogenous hCG, elevated estradiol levels, increased number of stimulated follicles during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (“necklace sign” or “string of pearls” appearance on US images), polycystic ovarian disease, and previous OHSS (Box 125.8).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Laboratory testing reveals serum estradiol levels elevated to higher than 3000 pg/mL, hemoconcentration with hyponatremia and hyperkalemia, and decreased renal function. Pelvic US with Doppler is essential to evaluate for the presence of ascites (Fig. 125.3) and the extent of follicular recruitment (Fig. 125.4) while ruling out alternative diagnoses such as ovarian torsion.

Treatment

No specific cure is available for OHSS; treatment is empiric and focused on supportive care until spontaneous resolution occurs (Table 125.7). The syndrome is usually self-limited.

Table 125.7 Management of Patients with Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome

| SEVERITY | SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | MANAGEMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Mild |

ART, Assisted reproductive technology; CBC, complete blood count; Cr, creatinine; Hct, hematocrit; Hg, hemoglobin; IV, intravenous; IVC, inferior vena cava; WBC, white blood cell.

Moderate Cases

Patients with moderate disease require a complete work-up, including laboratory tests and US, and hospitalization is recommended for close observation and serial examinations, as well as for symptomatic care if the patient has disabling nausea, intractable abdominal pain, tense ascites, abnormal laboratory values, or other indications of a downward trajectory. Pelvic examination is not recommended in moderate or severe cases because of the risk for cyst rupture with hemorrhage.16 There should be a low threshold for admission to the hospital for monitoring, but typically these patients are being very closely followed by their fertility specialist; if the symptoms are controlled adequately, the patient can be discharged to follow-up in the next 1 to 3 days. She should be instructed to maintain a record of fluid balance and avoid physical activity.

Severe Cases

Severe OHSS requires inpatient care in the intensive care unit.17 Strict monitoring of fluid balance and hemodynamics is critical. Large-bore IV access must be established for fluid resuscitation, and a subclavian line for central venous pressure is advised.

Prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis is essential given the high risk for thromboembolic disease.

Critical Cases

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Complications of Assisted Reproductive Technologies

Induction Phase

Abdominal pain, distention or ascites? Initiate a work-up and symptomatic treatment of OHSS. Obtain a US scan and estradiol levels.

Difficulty breathing and unstable? If signs of third spacing are present, suspect severe OHSS; start aggressive symptomatic and supportive treatment. Admit to the ICU.

Dyspnea with only leg edema or without any evidence of third spacing? Consider PE; obtain a chest radiograph. Anticoagulation and lower extremity vascular Doppler US are required to evaluate for DVT. If still equivocal, obtain a helical CT scan of the chest with IV contrast enhancement

After Oocyte Harvesting

Fever? Consider infection; administer antibiotics and evaluate whether stable for discharge.

Vaginal bleeding from a puncture site? Place pressure. If the bleeding does not stop, consider Monsel solution or silver nitrate.

Abdominal pain or peritoneal signs? Consider intraperitoneal hemorrhage; cardiovascular stabilization and definitive exploratory laparotomy are required.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome

Clarify the details of the anticipated therapeutic course.

Schedule follow-up with the patient’s physician in 1 to 3 days.

Instruct her to call her physician or return to the emergency department immediately if progressive symptoms of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome develop, including:

Warn the patient that there can be a second peak in symptoms after implantation triggered by her own hormonal surge.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Complications of Assisted Reproductive Technology

Increased abdominal girth, abdominal pain, edema, and dyspnea during induction of ovulation or early after implantation are suspicious for ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

Unilateral pelvic pain is suspicious for ectopic pregnancy or ovarian torsion.

Severe pain, fever, brisk bleeding, and peritoneal signs are suspicious for perforation.

Shortness of breath, possibly with pleuritic chest pain, should prompt evaluation for pulmonary embolism, although pleural effusions as a result of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome are also possible.

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2009 Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011.

2 Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000–2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(1):34.e1–34.e7.

3 Stany MP, Farley JH. Complications of gynecologic surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:343–359.

4 Magrina JF. Complications of laparoscopic surgery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:469–480.

5 Lam A, Kaufman Y, Khong SY. Dealing with complications in laparoscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23:631–646.

6 Walker WJ, Pelage JP, Sutton C. Fibroid embolization. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:325–331.

7 U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2007 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute; 2010. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/uscs

8 Jones RK, Kooistra K. Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43:41–50.

9 Sunderam S, Chang J, Flowers L, et al. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance—United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(5):1–25.

10 Grossman D, Blanchard K, Blumenthal P. Complications after second trimester surgical and medical abortion. Reprod Health Matters. 2008;16(31 Suppl):173–182.

11 Christin-Maitre S, Bouchard P, Spitz IM. Medical termination of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:946–956.

12 Pazol K, Gamble SB, Parker WY, et al. Abortion surveillance—United States, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(8):1–35.

13 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2002 Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Report: Section 5—ART trends, 1996–2002. Oct 17, 2005.

14 Budev MM, Arroglia AC, Falcone T. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(Suppl):S301–S306.

15 Vloeberghs V, Peeraer K, Pexters A, et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and complications of ART. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23:691–709.

16 Delvigne A, Rozenberg S. Review of clinical course and treatment of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:77–96.

17 Wright VC, Chang J, Jeng G, et al. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance—United States, 2003. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55:1–22.