CHAPTER 42 Complications of Elbow Arthroscopy

INFORMATION AND CLINICAL EXPERIENCE

Although suffering from a deserved reputation for significant potential complications, there is still relatively little information in the orthopedic literature regarding the frequency of complications from elbow arthroscopy. With the exception of a Mayo report, what data exist pertain to a single or limited case reports often associated with an anatomic study.1,3,6,19–22

ANATOMY

Joint Congruence and Capacity

The elbow is one of the most congruous joints in the body; hence, the ability to manipulate the joint to separate the articular surfaces and allow better visualization is extremely limited, and multiple portals may be needed.2,9,18 Furthermore, the capacity of the joint is limited in the normal situ-ation and is even further curtailed by most pathology. O’Driscoll and colleagues24 demonstrated an average normal capacity of approximately 30 mL. Post-traumatic and degenerative processes result in contracture of the joint, often allowing less than 10 mL of intra-articular distension. The soft tissue envelope of the elbow is extremely thin, the capsule being separated from the skin by a thin layer of subcutaneous tissue in some locations. Thus, the tendency for the portals to “seal” is limited. This feature predisposes to chronic drainage and the possibility of infection.15

Neurovascular Structures

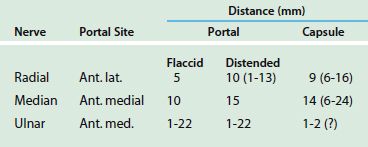

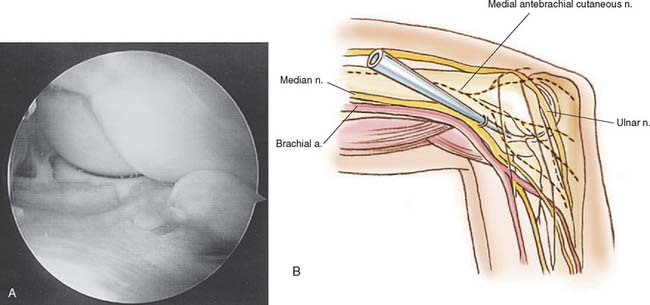

Without question, the greatest concern regarding elbow anatomy is the proximity of the radial and ulnar nerves that cross the joint in proximity to the capsule. The relationship of the radial, median, and ulnar nerves to the capsule in both the distended and the nondistended positions has been studied extensively.1,3,6,19–22,30,31,33 Furthermore, the vulnerability of cutaneous nerves had also been studied in relationship to the arthroscopic portal sites. These data are summarized in Table 42-1. It is particularly important to note that distension of the joint does alter the relative location of cutaneous nerves as well as the radial and median nerves referable to the portal site. However, a distended joint in no way protects either of these nerves from an intra-articular procedure.20 As a matter of fact, the distended capsule may theoretically render these nerves more, rather than less, vulnerable. The most vulnerable nerve anatomically is the posterior interosseous nerve.10 This nerve may typically be 5 to 10 mm from an anterolateral portal. However, there is significant variation, and in some instances. the nerve can be as close as 2 to 3 mm to the capsule because it lies over the radial neck. Similarly, the median nerve demonstrates a variation of approximately 5 mm between the distended and the nondistended capsule referable to the anteromedial portal. However, once again, the distended capsule approximates the nerve—it does not separate the nerve. Although it is clearly the most protected, median nerve injury has been reported.11 Of great concern is that of a concurrent injury to the brachial artery or vein. Finally, the ulnar nerve actually rests on the medial capsule.30 The greatest risk consists of procedures performed in the posteromedial corner of the elbow.12 However, injury from portal placement has also been reported.7

PATHOLOGY

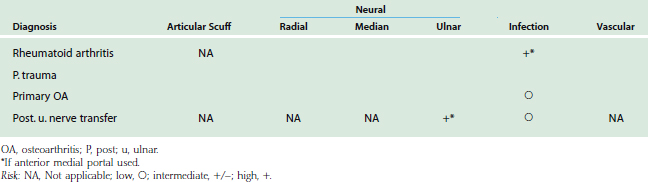

The nature of the pathology influences potential risks of complications22 (Table 42-2).

Rheumatoid Arthritis

The most common reason for arthroscopy of an elbow involved with rheumatoid arthritis is synovectomy. The capsule is extremely thin in these patients, and therefore, the nerves are at significant risk of injury with this procedure. One patient developed a temporary ulnar nerve paresthesia owing to the instability associated with rheumatoid synovitis and the vulnerability of the nerve referable to a thin capsule covered by proliferative synovium.

Loose Body

The removal of loose bodies is still probably the best and most common indication for elbow arthroscopy in both the degenerative and the post-traumatic elbow.4,23,25,27 The complications are uncommon unless the portal site strays from the recommended positions or débridement is required. Both generally place the radial nerve at risk.

Degenerative Arthritis

Primary degenerative arthritis is a good indication for elbow arthroscopy.4,14 The se-lection of a procedure may include removal of loose bodies, débridement of the coronoid and olecranon osteophytes, and anterior and posterior capsular release. The anterior capsular release places the median and, particularly, the radial nerve at risk. The posterior release may place the ulnar nerve at risk. In addition, the multiple portal sites necessary for effectively carrying out this procedure may further add an element of vulnerability to these nerves. In addition to the degenerative as well as the post-traumatic elbow, the capsular capacity is very limited,24 making even a diagnostic procedure something of a risk particularly for articular scuffing. As confidence increases and a greater amount of bone is removed, the potential for ectopic bone has also been reported8 (Fig. 42-1).

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

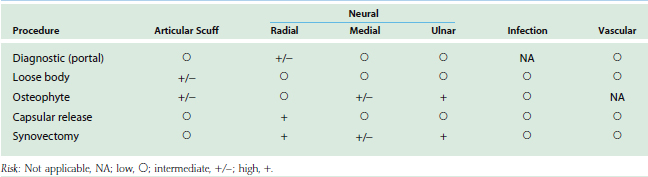

In addition to variation in pathology as implied previously, different risks are also associated with varying complexities of surgical procedures (Table 42-3).22

Capsular Release

A capsular release may be the most dangerous arthroscopic procedure.14,22 The capsule is usually thick, and the joint capacity limited. Some débridement may be required to obtain adequate visualization. The radial nerve is at particular risk because it is often closely applied to the anterior capsule at the radial head. As noted earlier, the ulnar nerve is valuable to posterior capsular release. Injury to the median nerve may also occur but at a lower risk.

Synovectomy

Complication from synovectomy is a function of the aggressiveness of the procedure.9 Multiple portals do place the nerves at some risk, even for the diagnostic component. In addition, the thin capsule generally present in the rheumatoid patient may unknowingly be violated, thus immediately placing the anterior nerves at risk. Furthermore, use of low suction may draw the nerve into the débriding instrument. Finally, the pathology itself frequently makes visualization difficult, and débridement to attain better visua-lization may violate the capsule, thus increasing the vulnerability to nerve injury. With care, these problems can be avoided. We have recently documented no permanent nerve problems after 83 elbow synovectomies. Of note, however, was that 6 did have some transient paresthesias of the radial (three) and ulnar (three) nerves.5

VASCULAR INSULT

To date, we were unable to identify any document-ation of vascular injury or compartment syndrome after elbow arthroscopy. The marked swelling that may occur quickly resolves. It has been shown that infusion systems that control both pressure and flow cause less extravasation than systems that control pressure alone.26

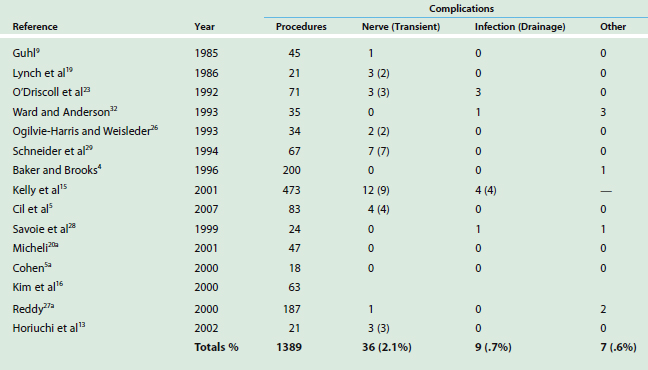

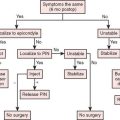

INCIDENCE

A review of the literature reveals that the greatest focus is placed on neural injury, documented in about 2.1% of patients, although this is usually transient (Table 42-4). Infection and all other problems are not commonly reported. Overall, a review of more than 600 procedures reveals some form of complication in 5%.4,5,9,13,16,19,23,25,29,32 We consider this an inaccurate estimate of the reality.15

Mayo Clinic Experience

Because the potential risk is high and owing to a lack of information in the literature regarding the true incidence of elbow arthroscopy complications, we have reviewed our experience with elbow arthroscopy.15 After 449 procedures, 1% of individuals have a significant complication requiring treatment or altering outcome. There were no permanent neural vascular injuries in this series. Furthermore, 10% have a nonpermanent “problem” associated with the procedure. The data in Tables 42-3 and 42-4 reflect this experience.

PREVENTION

The recommendations for avoiding complications of elbow arthroscopy are generally well recognized: (1) define landmarks before distension; (2) recognize that distension protects the nerve from portal injury but not from capsular procedures; (3) portals more proximal to the joint tend to be safer30; (4) keep the elbow flexed 90 degrees to increase the distance between the nerves and the capsule; (5) do not use pressurized infusion26; (6) débriding with radius pronated protects the posterior interosseous nerve; (7) always visualize the instrument tip; (8) avoid suction around a nerve; (9) capsular “retraction” may be useful; and (10) use local anesthesia judiciously because this can cause neural anesthesia, which confuses the patient’s postoperative status. Most important, recognize the potential risk and be realistic about your competency.

1 Adolfsson L. Arthroscopy of the elbow joint: A cadaveric study of portal placement. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:53.

2 Andrews R.J., Carson W.G. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:97.

3 Angelo R.L. Advances in elbow arthroscopy. Orthopedics. 1993;16:1037.

4 Baker C.L., Brooks A.A. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Clin. Sports Med. 1996;15:261.

5 Cil, A., Veillette, C. J. H., O’Driscoll, S. W., and Morrey, B. F.: Arthroscopic Synovectomy of the Elbow in Inflammatory Arthritis. Submitted for publication, 2007.

5a Cohen A.P., Redden J.F., Stanley D. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow: A comparison of open and arthroscopic debridement. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:701.

6 Drescher H., Schwering L., Jerosch J., Herzig M. The risk of neurovascular damage in elbow joint arthroscopy: Which approach is better: Anteromedial or anterolateral? Z. Orthop. Ihre Grenzgeb. 1994;132:120.

7 Dumonski M.L., Arciero R.A., Mazzocca A.D. Ulnar nerve palsy after elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:577.e1.

8 Gofton W.T., King G.J. Heterotopic ossification following elbow arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:E2.

9 Guhl J.F. Arthroscopy and arthroscopic surgery of the elbow. Orthopedics. 1985;8:1290.

10 Gupta A., Sunil T.M. Complete division of the posterior interosseous nerve after elbow arthroscopy: A case report. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:566.

11 Haapaniemi T., Berggren M., Adolfsson L. Com-plete transection of median and radial nerves during arthroscopic release of post-traumatic elbow contracture. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:784.

12 Hahn M., Grossman J.A. Ulnar nerve laceration as a result of elbow arthroscopy. J. Hand Surg. 1998;23B:109.

13 Horiuchi W., Momohara S., Tomatsu T., et al. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84A:342.

14 Jones G.S., Savoie F.H. Arthroscopic capsular release of flexion contractures (arthrofibrosis) of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:277.

15 Kelly E., Morrey B.F., O’Driscoll S. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83A:25.

16 Kim S.J., Kim H.K., Lee J.W. Arthroscopy for limitation of motion of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:680.

17 Lee B.P.H., Morrey B.F. Arthroscopic synovectomy of the elbow for rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79B:770.

18 Lindenfeld T.N. Medial approach in elbow arthroscopy. Am. J. Sports Med. 1990;18:413.

19 Lynch G.J., Myers J.F., Whipple T.L., Caspari R.B. Neurovascular anatomy and elbow arthroscopy: Inherent risks. Arthroscopy. 1986;2:191.

20 Marshall P.D., Fairclough J.A., Johnson S.R., Evans E.J. Avoiding nerve damage during elbow arthroscopy. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75B:129.

20a Micheli L.J., Luke A.C., Mintzer C.M., Waters P.M. Elbow arthroscopy in the pediatric and adolescent population. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:694.

21 Miller C.D., Jobe C.M., Wright M.H. Neuroanatomy in elbow arthroscopy. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:168.

22 Morrey B.F. Complications of elbow arthroscopy. Instr. Course Lect. 2000;49:255.

23 O’Driscoll S.W., Morrey B.F., An K.N. Intraarticular pressure and capacity of the elbow. Arthroscopy. 1990;6:100.

24 O’Driscoll S.W., Morrey B.F. Arthroscopy of the elbow: Diagnostic and therapeutic benefits and hazards. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:84.

25 Ogilvie-Harris D.J., Schemitsch E. Arthroscopy of the elbow for removal of loose bodies. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:5.

26 Ogilvie-Harris D.J., Weisleder L. Fluid pump systems for arthroscopy: A comparison of pressure control versus pressure and flow control. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:591.

27 Poehling G.G., Ekman E.F. Arthroscopy of the elbow. Instr. Course Lect. 1995;44:217.

27a Reddy A.S., Kvitne R.S., Yocum L.A., Elattrache N.S., Glousman R.E., Jobe F.W. Arthroscopy of the elbow: a long-term clinical review. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:588.

28 Savoie F.H.3rd, Nunley P.D., Field L.D. Arthroscopic management of the arthritic elbow: Indications, technique, and results. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:214.

29 Schneider T., Hoffstetter I., Finnk B., Jerosch J. Long-term results of elbow arthroscopy in 67 patients. Acta Orthop. Belg. 1994;60:378.

30 Stothers K., Day B., Regan W.R. Arthroscopy of the elbow: Anatomy, portal sites, and a description of the proximal lateral portal. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:449.

31 Verhaar J., van-Mameren H., Brandsma A. Risks of neurovascular injury in elbow arthroscopy: Starting anteromedially or anterolaterally? Arthroscopy. 1991;7:287.

32 Ward W.G., Anderson T.E. Elbow arthroscopy in a mostly athletic population. J. Hand Surg. 1993;18:220.

33 Unlu M.C., Kesmezacar H., Akgun I., Ogut T., Uzun I. Anatomic relationship between elbow arthroscopy portals and neurovascular structures in different elbow and forearm positions. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:457.