47 Complications of Bariatric Surgery

• Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is the most commonly performed bariatric procedure in the United States.

• Pulmonary embolism (30% to 40%) is the most common cause of death after bariatric surgery, followed by cardiac events (25%) and anastomotic leaks (20%). Dumping syndrome, wound infections, strictures, and stomal ulcerations are common complications.

• Acute gastric distention is a rare but potentially deadly early postoperative complication that requires decompression.

• A nasogastric tube could perforate the pouch site in patients who have recently undergone surgery.

• Abdominal pain without vomiting in the early postoperative weeks might represent a small bowel obstruction or internal hernia.

• Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) is the most commonly performed bariatric procedure in Europe and is becoming more common in the United States.

• Acute anterior or posterior gastric band slippage is the most common complication of LAGB requiring emergency treatment (band deflation).

• LAGB has the lowest morbidity and mortality of all currently performed bariatric procedures.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of morbid obesity has risen more than fourfold since 1986.1 Currently, 1.7 billion people worldwide are considered obese and approximately 60% of the U.S. population is overweight. In excess of 100 billion dollars is spent annually on obesity health care–related costs.

To be considered morbidly obese, one must have either a body mass index (BMI) greater than 40 kg/m2 or a BMI of 35 to 40 kg/m2 with comorbid conditions.2 More than 15 million Americans currently have BMI levels that make them eligible for bariatric surgery.3 In the United States only about 1% of eligible patients undergo bariatric surgery.

Morbid obesity promotes the development of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, gastroesophageal reflux, asthma, and obstructive sleep apnea. Premature death from obesity now rivals the mortality rates related to smoking, with more than 300,000 deaths attributable to obesity per year.4

Bariatric surgery is the most effective and durable treatment to achieve weight loss and its associated comorbidity. Five-year mortality is reduced 89% in severely obese patients who undergo weight loss surgery.5,6 Fifteen-year survival increases by one third in patients who undergo bariatric surgery in comparison with those who do not. New laparoscopic surgical techniques have contributed to the growing demand for and acceptance of bariatric surgery. Approximately 4925 bariatric procedures were performed in 1990, as compared with an estimated 220,000 in 2008. Bariatric surgery is now the second most common abdominal operation in the United States.

Recent trends suggest that higher-risk, older patients are undergoing bariatric procedures with greater frequency; surprisingly, they demonstrate postoperative morbidity and mortality rates similar to those in the general population.7 Rates of perioperative complications, reoperation, hospital readmission, and emergency department (ED) visits have been falling. The rates for these indicators are highest with gastric bypass followed by sleeve gastrectomy and lowest for laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB).8 Overall, in-hospital mortality rates are between 0.05% and 0.2%, and 30-day mortality rates have been reported to range between 0.05% and 2%.

Complications of bariatric surgery are common and are generally initially treated in the ED. Up to 20% of patients are admitted for a postoperative complication within 1 year of the bariatric procedure; this rate increases to 40% within 3 years. The potential postoperative complications of the various bariatric procedures have predictable timing and clinical manifestations.9

Types of Bariatric Surgery: Roux-en-Y and Gastric Banding

The two most common types of bariatric surgery in the United States are the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP) (54%) and adjustable gastric banding (39%). Adjustable gastric banding continues to rapidly gain in popularity since initial federal approval in 2001.7

Malabsorption

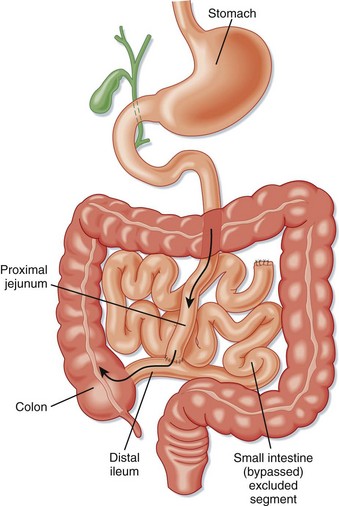

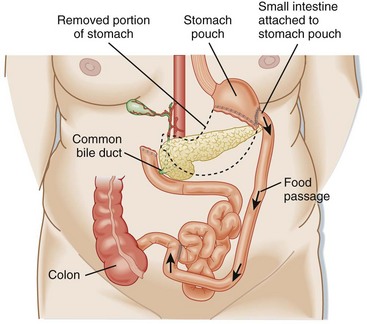

Surgical techniques that induce malabsorption were the first attempted. Malabsorptive techniques were thought to be the most effective method of achieving rapid and sustained weight loss. Surgeons initially connected the proximal jejunum to a distal portion of the ileum or ascending colon in a procedure known as jejunoileal bypass (Fig. 47.1). This technique resulted in severe diarrhea, dangerous metabolic derangements, arthropathy, renal calculi, gallstones, liver disease, and short bowel syndrome. Gastric bypass has been shown to be a more effective malabsorptive procedure with fewer side effects than those associated with jejunoileal bypass. Malabsorptive procedures still in current use include laparoscopic RYGBP, BPD, duodenal switch, and isolated intestinal bypass.

Restriction

Purely restrictive procedures are less effective than malabsorptive techniques.6 Restrictive surgeries act by reducing oral intake through induction of early satiety. However, some areas of the stomach easily dilate over time, which causes gradual increases in perceived hunger and subsequent food intake. Restrictive procedures are more successful when the lesser-curve gastric pouch is 15 mL or smaller.4 Restrictive weight loss procedures such as vertical banded gastroplasty and isolated partial gastrectomy (sleeve gastrectomy) have fallen out of favor. LAGB is the most common, poses the least risk, and is the most effective restrictive technique currently performed.10

Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass

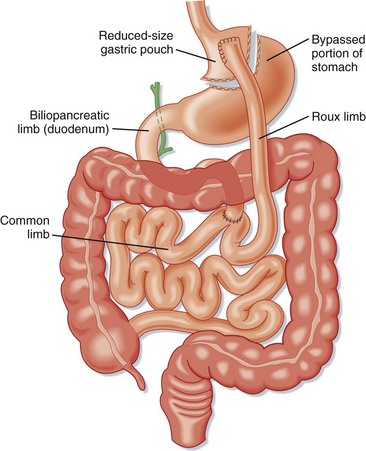

The RYGBP procedure creates a gastric pouch from the proximal portion of the lesser curvature of the stomach that can hold about 15 to 30 mL of fluid and food (Fig. 47.2). A portion of the distal end of the small bowel is connected to this pouch to create a concurrent malabsorptive process. Historically, RYGBP was an open procedure, but currently the majority are performed laparoscopically.

Late complications generally involve both anatomic and systemic complications. Anatomic complications include esophageal reflux, chronic abdominal pain, internal hernias, ulcers, stricture, stenosis, and bowel obstruction. Systemic complications are manifested mostly as nutritional deficiencies.11 Clinical manifestations include anemia (iron deficiency), osteopenic fractures (calcium deficiency), fatigue and lower extremity edema (protein-calorie malnutrition), chronic pain and proximal muscle weakness (vitamin D deficiency), visual deficits (vitamin A deficiency), and vague neurologic symptoms (thiamine, folate, and vitamin B12 deficiencies).

Specific Clinical Presentations

The occurrence of acute fever and tachycardia within weeks of a Roux-en-Y procedure suggests an anastomotic leak with or without abscess formation. The symptoms are often subtle but can include dyspnea, unexplained sepsis, changes in mental status, and restlessness. Peritoneal signs are often lacking. Because abdominal examination of morbidly obese patients is unreliable, the diagnosis is best accomplished through imaging studies. CT of the abdomen and pelvis with oral and intravenous (IV) administration of a contrast agent is the modality of choice. If the patient is unable to undergo CT because of the weight limitations of the CT table, an upper GI radiographic series should be obtained. The false-negative rate is high (up to 44%) with CT and other imaging studies for the evaluation of anastomotic leaks. Laparoscopy should be considered in cases of negative imaging but high pretest probability of an anastomotic leak.12,13

Constipation may result from decreased fiber intake.

Bleeding may occur at any anastomotic site but is most common and dangerous in the gastrojejunostomy area. It often results in melena, hematemesis, hematochezia, or hypotension (or any combination of these findings) secondary to upper GI bleeding. Upper endoscopy is the most reliable way to confirm blood loss from this site. Bleeding at other anastomotic sites (jejunojejunostomy and the transected gastric remnant) is usually self-limited and managed nonoperatively.11 Stomal ulcers can occur 2 to 4 months after surgery and are identified by endoscopy. Many can be treated on an outpatient basis with proton pump inhibitors or sucralfate.

Laparoscopic Adjustable Gastric Banding

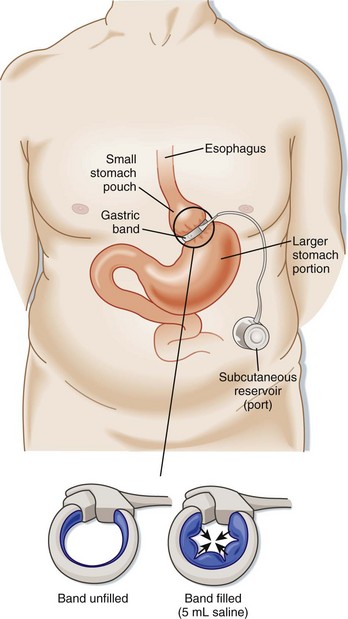

The LAP-BAND (Allergan, Inc., Irvine, CA) is an adjustable device that is laparoscopically secured around the upper portion of the stomach (Fig. 47.3). The band is connected by a tube to a port implanted under the skin. Surgeons may adjust the extent of constriction (restriction) of the LAP-BAND by injecting saline into the subcutaneous port. Increased restriction limits food intake; adjustments can be made in response to adverse symptoms or patient preference, thereby allowing some control over the weight loss process. Operative risks for LAGB are less than those for RYGBP.

Complications

Any patient with signs of obstruction after LAGB should undergo immediate deflation of the band. Emergency physicians can deflate an adjustable gastric band by accessing the subcutaneous anterior abdominal port (see Fig. 47.3). A noncoring Huber needle should be used to remove the amount of saline injected during the previous two adjustments. The patient should know this volume of saline, but if not, one can aspirate all the saline in the reservoir. Fluoroscopy or ultrasound may be required if the port cannot be accessed easily. A GI swallow study and surgical consultation should be obtained after any band deflation. Symptoms should resolve over a couple of days after deflation. Surgery is often required to definitively repair gastric band slippage.

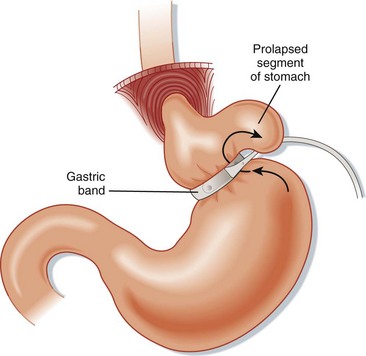

Gastric necrosis of the stomach wall is a late complication that often results from ischemia caused by a combination of gastric prolapse—the part of the stomach below the band herniates up through the device (Fig. 47.4) and pressure from the band. Patients appear ill, with an acute abdomen. Upper GI studies or CT scans show an overly distended gastric pouch. Patients require emergency surgery to remove the band and repair the stomach wall.

Esophageal and gastric pouch dilation occurs when the band is too tight or patients are not compliant with their diet. The symptoms are similar to those seen with gastric slippage. Upper GI contrast studies make the diagnosis. Treatment is band deflation and close follow-up with the bariatric physician. Prolonged dilation can result in chronic esophageal dysmotility, severe achalasia, and GERD, which is not always reversible (13%) with band deflation and removal.14

Recent controversies have arisen regarding the long-term complications of gastric banding. Few long-term studies have been performed, but a recent 14-year study (1995 to 2009) of gastric band surgery showed high complication and reoperation rates. Reoperation because of complications was reported to occur in 30% of patients, band removal was needed in 12%, and weight regain began after 5 years of follow-up.15 Still, gastric banding has been shown to have a lower mortality rate than other bariatric surgeries, is less invasive, and is reversible.

Biliopancreatic Diversion

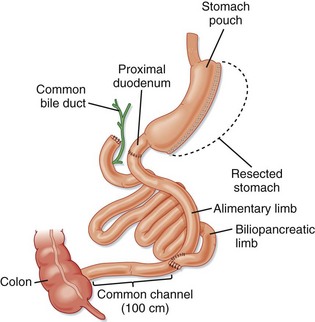

BPD is popular in Italy (Fig. 47.5). The procedure involves a distal gastrectomy that leaves a 250-mL stomach capacity with a drastic intestinal bypass. Half of the jejunum and ileum are disconnected and reconnected near the terminal ileum. This procedure is particularly effective for severely obese patients (BMI > 50 kg/m2), in whom it causes significant weight loss and reduced morbidity. Less bacterial overgrowth occurs in the bypassed intestine because it is continuously exposed to bile and pancreatic enzymes. Serious complications can result, however, particularly the metabolic abnormalities and nutritional deficiencies seen after aggressive malabsorptive procedures. Hepatic dysfunction can develop in 2% of patients undergoing BPD.

Duodenal Switch and Sleeve Gastrectomy

The duodenal switch procedure is similar to BPD, but the jejunum is connected to the proximal duodenum rather than the ileum (Fig. 47.6). This operation is also known as the biliopancreatic diversion–duodenal switch (BPD-DS) procedure. It is considered an improvement on BPD alone because the length of the small intestine is increased to 100 cm, which allows better absorption of nutrients.

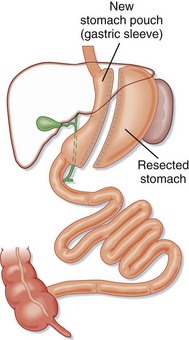

Some surgeons prefer to perform only a sleeve gastrectomy in high-risk patients (Fig. 47.7). This simple restrictive procedure avoids intestinal bypass and anastomoses of the GI tract. Side effects such as nutritional deficiencies are rare because only mild malabsorption results from sleeve gastrectomy alone.

Complications of Bariatric Surgery

General Complications

Serious complication rates are lower in hospitals with a high volume of bariatric surgery procedures.16

Procedure-Specific Complications

Box 47.1 lists the most common GI complications of bariatric surgery.12

Box 47.1

Top 10 Complications of Bariatric Surgery

2. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies

6. Bowel obstruction and anastomotic stenosis

7. Gastric and stomal ulceration

10. Perioperative death (pulmonary embolism, sepsis, myocardial infarction)

From Abell TL, Minocha A. Gastrointestinal complications of bariatric surgery: diagnosis and therapy. Am J Med Sci 2006;331:214-8.

Anastomotic (Staple Line) Leak

Anastomotic leaks most often occur in the immediate postoperative period, although some leaks are not apparent until weeks after surgery. GI leaks are one of the most serious and potentially deadly complications of gastric bypass surgery. The incidence is up to 6% in patients after first procedures, but it rises 5-fold to 10-fold in patients who undergo revision of the initial procedure. Leaks are difficult to diagnose because of initial nonspecific signs and symptoms: low-grade fever, abdominal tenderness, tachypnea and respiratory insufficiency, tachycardia, left shoulder pain, anxiety, and a feeling of impending doom. An upper GI radiographic series or abdominal CT scan sometimes confirms the diagnosis by demonstrating extravasation of the oral contrast agent (Gastrografin). However, an upper GI series or CT scan often misses the leak. Many bariatric surgeons question the need for confirmatory studies and believe that patients should be taken to the operating room for laparoscopic examination when tachycardia greater than 120 beats/min and symptoms indicative of a leak are present.17 The most common site of the leak is the gastrojejunostomy anastomosis. Interventional or surgical management is required. Early antibiotic therapy is recommended.

Acute Gastric Distention

Tips and Tricks

Consult the bariatric surgeon or gastroenterologist (if endoscopy is required) early for patients who have previously undergone bariatric surgery.

Do not place a nasogastric tube in patients who have undergone gastric bypass without consultation from the bariatric surgeon. Blind placement of such a tube may result in perforation of the pouch site, particularly in the immediate postoperative period.

Laparoscopy is often required for definitive diagnosis of internal hernias and anastomotic leaks.

Small gastric pouches limit the amount of oral contrast agent that patients can ingest for a computed tomography scan. If contrast is required, patients should be told to sip as much contrast agent as they feel comfortable taking over a 3-hour period before imaging. The scan is then performed, regardless of the amount of contrast ingested.12

Stomal Ulceration

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

The American Society for Bariatric Surgery’s website has excellent educational resources (www.asbs.org).

The patient should return to the hospital if nausea, vomiting, or a fast heart rate develops.

Blood glucose levels can fluctuate widely after weight loss surgery and require close monitoring.

Patients must adhere strictly to the postoperative diet instructions to prevent potential complications.

Edwards ED, Jacob BP, Gagner M, et al. Presentation and management of common post–weight loss surgery problems in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:160–166.

Ellison SR, Ellison SD. Bariatric surgery: a review of the available procedures and complications for the emergency physician. J Emerg Med. 2008;34:21–32.

Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75:103–112.

Trus TL, Pope GD, Finlayson RG. National trends in utilization and outcomes of bariatric surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:616–620.

1 Sturm R. Increases in clinically severe obesity in the United States, 1986-2000. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2146–2148.

2 Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity: proceedings of a National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(Suppl):487S–619S.

3 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS). fact sheet. Available at www.asmbs.org, 2009.

4 Crookes PF. Surgical treatment of morbid obesity. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:243–264.

5 Christou NV, Sampalis JS, Liberman M, et al. Surgery decreases long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:416–423.

6 Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–1737.

7 Santry HP, Gillen DI, Lauderdale DS. Trends in bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA. 2005;294:1909–1924.

8 Birkmeyer NJ, Dimick JB, Share D. Hospital complication rates with bariatric surgery in Michigan. JAMA. 2010;304:435–442.

9 Zingmond DS, McGory ML, Ko CY. Hospitalization before and after gastric bypass surgery. JAMA. 2005;294:1918–1924.

10 Kelly J, Tarnoff M, Shikora S, et al. Best practice recommendations for surgical care in weight loss surgery. Obes Res. 2005;13:227–233.

11 Edwards ED, Jacob BP, Gagner M, et al. Presentation and management of common post–weight loss surgery problems in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:160–166.

12 Abell TL, Minocha A. Gastrointestinal complications of bariatric surgery: diagnosis and therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331:214–218.

13 Monkhouse SJW, Morgan JDT, Norton SA. Complications of bariatric surgery: presentation and emergency management—a review. Ann R Col Surg Engl. 2009;91:280–286.

14 Naef M, Wolfgang WG, Naef U, et al. Esophageal dysmotility disorders after laparoscopic gastric banding—an underestimated complication. Ann Surg. 2011;253:285–290.

15 Stroh C, Hohmann U, Schramm H, et al. Fourteen-year long-term results after gastric banding. J Obes. 2011;2011:128451.

16 Birkmeyer NJO, Dimick JB, Share D, et al. Hospital complication rates with bariatric surgery in Michigan. JAMA. 2010;304:435–442.

17 Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75:103–112.