CHAPTER 60 Complications and corrections of lipoplasty

Introduction

Lipoplasty or liposuction is a surgical procedure used to treat and reshape the body. It is an elective procedure that is typically performed on healthy patients who wish to improve their contour. Liposuction is becoming the most common procedure performed by plastic surgeons in the entire world, and is a very safe procedure today. However, it carries with it certain risks and complications, including a death rate of 1/5000 procedures.1 Risks can be minimized or avoided by a well-trained surgeon and surgical team.

History

Dujarrier first attempted to remove subcutaneous fat with a uterine curette, but tragic complications eventually evolved to necrosis and amputation, possibly due to vascular injury or infection.2 It was the first complication described for a lipoplasty attempt.

No technical innovations were achieved until 1982, when Joseph Schrudde used a delicate curette to correct lipodystrophy, significantly reducing blood loss.3

The senior author was one of the pioneers of the careful approach of the superficial layer of the abdomen which was, before this, responsible for many contour irregularities, as a consequence of treatment of the deeper layer. The same author included the back region and, progressively, included other areas, noting significant retraction of the skin and a better contour. He also observed that, with no superficial approach, it was difficult to obtain good results in the presence of scars or depressions.4 It was Gasparotti5 who named this technique “superficial liposuction” and promoted it internationally. The development of new techniques, new cannulas, better anesthesia and the better training of the surgeon are helping to ensure patients’ safety and the efficacy of the procedure.

Complications

| 1. Injecting too much fluid and local anesthesia |

| 2. Removing too much fat |

| 3. Performing too many procedures in the same surgical act |

| 4. Wrong indication for the procedure |

| 5. Inadequate monitoring |

*Grazer FM, de Jong RH. Fatal Outcomes from liposuction: census survey of cosmetic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;105:436–446.

Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

Therefore, a mandatory preoperative evaluation to identify factors of risk for thrombosis, as well as the use of elastic stockings, pneumatic systems of intermittent compression, adequate hydration and early mobilization are usually sufficient to prevent venous thrombosis in healthy patients undergoing lipoplasty.

Lidocaine and adrenaline toxicity

The FDA defines 7 mg/kg as the maximum safe dose of lidocaine with epinephrine (and 5 mg/kg for lidocaine only) for regional anesthesia. Literature on liposuction reports the use of lidocaine in doses of up to 33–35 mg/kg,1 but always in solutions with adrenaline and with low concentration of lidocaine (0.1%) in large volume infiltration. Since the subcutaneous area is able to retain lidocaine, it is be restricted to the infiltration site, and only the exceeding molecules (1 mg of lidocaine for 1 g of tissue) would be available to be submitted to conventional pharmacokinetics. Hepatic function is an important factor that interferes in the concentration of lidocaine. Even drugs which interact with lidocaine in the hepatic cytochromes, such as antidepressants, might raise the serum concentration of lidocaine, causing signs of toxicity in the central nervous and cardiac systems. The hepatic metabolization of lidocaine and adrenaline reaches its serum peak within three hours after infiltration, returning to normal values after 12 hours.6

Fat emboli

According to Fourme and colleagues fat embolism syndrome is a very rare occurrence that has been reported infrequently after liposuction alone.7 Therefore, some authors think that the incidence of this complication after liposuction must be revised, because diagnosis is difficult and the clinical pattern is not specific.

Local complications

Irregularities and depressions

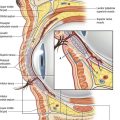

This kind of complication is best defined as an undesirable consequence of liposuction. They often occur when the basic principles of the technique are not respected. There are areas with low potential for retraction and which are difficult to approach. We have to remember that the disposition and characteristics of the fat cells, the density of the conjunctive septi among them, as much as the structure of the collagen within the superficial and deep layers of the fat tissue are different in each part of the human body, as described by De Souza Pinto.4,8

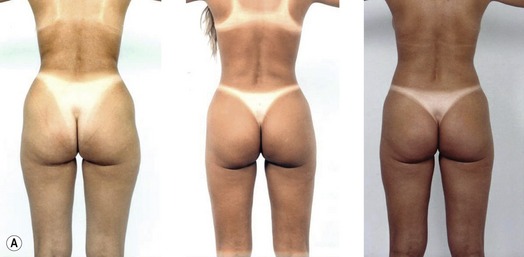

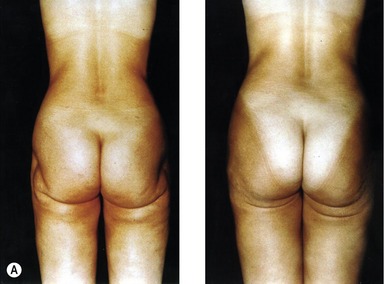

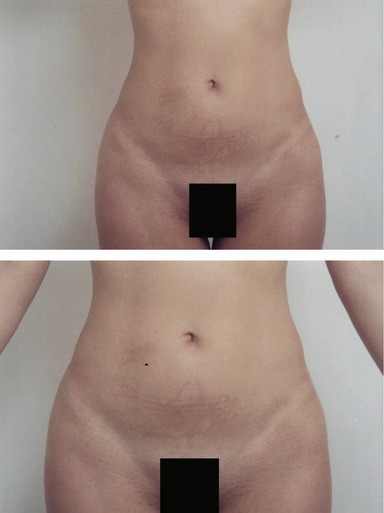

In the treatment of insufficient fat removal or located fat build-up (undercorrection) (Fig. 60.1), careful liposuction must be performed progressively, with thin cannulas (2–3 mm) (Fig. 60.2), to avoid causing an abrupt subcutaneous fault, and to improve local cutaneous retraction (Fig. 60.3).

To treat irregularities and depression, we break the adherences with a ring cannula (Fig. 60.4) and then perform fat injections to improve the skin (Fig. 60.5).

Folds in the compressive garment can also cause irregularities, and the use of foam under the mesh and adequate postural positioning is recommended.

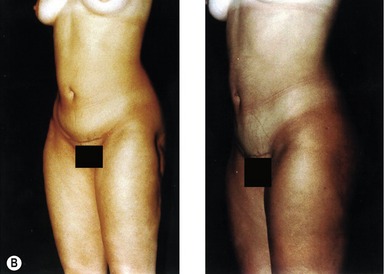

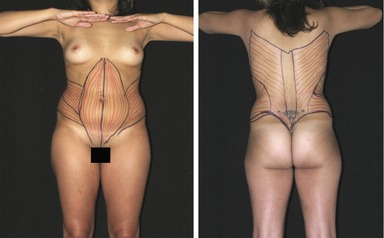

In our procedure, we perform VASER® and “lipomioplasty” techniques that respect the anatomy of the body muscles by moving the cannulas in the same direction of the muscle fibers (Fig. 60.6). This achieves better body contouring with enhanced skin retraction. The sum of these two procedures promotes high quality results with decreased areas of irregularities.

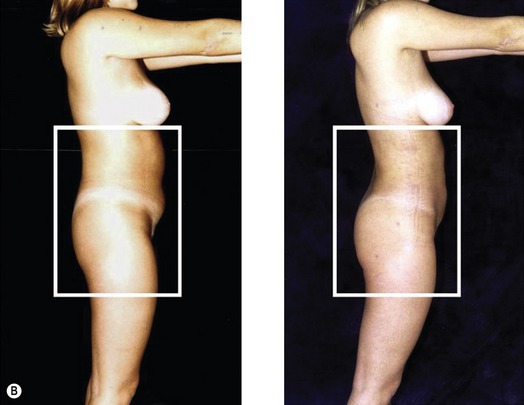

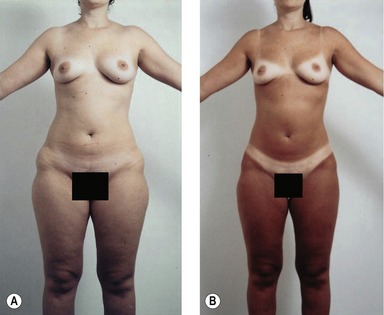

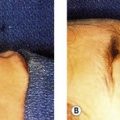

Skin excess

The evaluation of the amount of fat to be aspirated and the skin excess that can be treated by postsurgical cutaneous retraction is done subjectively, based on physical exam data and the surgeon’s experience (Fig. 60.7). If the patient has dramatic skin excess, we prefer to perform the procedure with skin resection.

Unaesthetic scars

The incisions must always be placed where they can be hidden and allow easy access and passage of the cannulas. Very small incisions can increase the rubbing of the cannula against the skin and this may cause low-quality scars.

Seromas

We minimize seromas by using drains in the subcutaneous areas, which present high volumes on the first day after surgery, for the first 24 h on average, and providing manual lymphatic drainage. Compressive garments (with a stable compression rate less than the central venous pressure) immediately after surgery can help to prevent seromas and minimize pain by reducing the mobility of all aspirated tissue.

Conclusion

In the beginning, the complications of lipoplasty were predominantly local, because the procedure was restricted to anatomical regions, and because of the precariousness of the surgical instruments, with cannulas of thick bore, resulting in postoperative deformities of the surface. The evolution of the instruments and new approaches to lipomioplasty have minimized these complications, enabling superficial lipoplasty to be a satisfactory method of improving the body contour (Fig. 60.10).

1. Mélega JC, Kawasaki MC, Castagnetta F, Santos MS. Lipoaspiração – Problemas e Soluções. Cirurgia Plástica – Fundamentos e ArteMedsi Rio de Janeiro. 2003:639–650.

2. Avelar J, Illouz YG. Lipoaspiraçäo. Säo Paulo: Editora Hipáciates; 1986.

3. Schrudde J. Suction curettage for body contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:903–904.

4. De Souza Pinto EB. Lipoaspiração superficial. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 1999.

5. Gasparotti M. Superficial liposuction: A new application of the technique for aged and flaccid Skin. Aesth Plast Surg. 1992;16:141–153.

6. Grazer FM, de Jong. Perioperative management of cosmetic liposuction. Plast Reconst Surg. 2001;107:1039–1044.

7. Fourme J, Vieillard-Baron A, Loubiéres Y, et al. Early fat embolism after liposuction. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:782–784.

8. De Souza Pinto BB, da Rocha RP, Filhjo WQ, et al. Morphohistological analysis of abdominal skin as related to liposuction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:153–158.

Da Rocha RP, da Rocha ELP, de Souza Pinto EB, Sementilli A, Nakanishi CP. Cutis marmorata resemblance after liposuction. Aesth Plast Surg. 2005;29:310–312.

De Souza Pinto EB, Saldanha OR, da Rocha RP, et al. Metodologia experimental para testar cânulas de lipoaspiração. Revist Soc Bras Cir Plast. 2005;20:30–35.

Samdal F, Amland PF, Bugge IF. Blood loss during liposuction using the tumescent technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 1994;18(2):157–160.

Toledo LS, Mauad R. Complications of body sculpture: Prevention and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:1–11.