Chapter 13 Complementary and Alternative medicine

In addition to rational phytotherapy, which is a science-based, empirical approach to the use of medicinal plants in the treatment and prevention of disease, in developed countries there are other healthcare approaches involving the use of plants. The most popular of these non-conventional approaches are discussed in this chapter (Box 13.1 and 13.2).

Medical herbalism

Modern herbalism

• A patient’s psychological and emotional wellbeing, as well as physical health, is considered, resulting in the claim that a holistic therapy is offered.

• Herbalists select herbs on an individual basis for each patient (in line with the holistic approach), thus it is likely that even patients with the same physical symptoms will receive different combinations of herbs.

• Herbalists also aim to identify the underlying cause (e.g. stress) of a patient’s illness and to consider this in the treatment plan.

• Herbs are used to stimulate the body’s healing capacity, to ‘strengthen’ bodily systems and to ‘correct’ disturbed body functions rather than to treat presenting symptoms directly.

• Herbs may be used, for example, with the aim of ‘eliminating toxins’ or ‘stimulating’ the circulation. The intention is to provide long-term relief from the particular condition.

Importantly, different constituents of a medicinal plant are seen as acting together in some (undefined) way that has beneficial effects. For example, the constituents may have additive effects, or interact to produce an effect greater than the total contribution of each individual constituent (known as ‘synergy’), or the effects of one constituent reduce the likelihood of adverse effects due to another constituent. Similarly, it is also believed that some combinations of different herbs interact in a beneficial way. There is some experimental (but little clinical) evidence that such interactions occur, although it cannot be assumed that this is the case for all herbs or for all combinations of herbs. Synergy is discussed in detail in Chapter 11.

Herbalists’ prescriptions

A first consultation with a herbalist may last for an hour or more, during which the herbalist will explore the detailed history of the illness. Generally, a combination of several different herbs (usually four to six) is used in the treatment of a particular patient. Some examples of such combinations are given in Table 13.1, although there are no ‘typical’ prescriptions for specific conditions; as stated above, even patients with the same condition are likely to receive different prescriptions. Sometimes, a single herb may be given, for example, Vitex agnus-castus (chasteberry) for premenstrual syndrome and dysmenorrhoea. Each patient’s treatment is reviewed regularly and is likely to be changed depending on whether or not there has been a response.

| Plant | Plant part |

|---|---|

| Menopausal symptoms | |

| Cimicifuga racemosa (black cohosh) | Roots, rhizome |

| Leonorus cardiaca (motherwort) | Aerial parts |

| Hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) | Aerial parts |

| Alchemilla vulgaris (Lady’s mantle) | Aerial parts |

| Stress | |

| Passiflora incarnata (passion flower) | Aerial parts |

| Valeriana officinalis (valerian) | Root |

| Verbena officinalis (vervain) | Aerial parts |

| Leonorus cardiaca (motherwort) | Aerial parts |

Comparison of herbalism with rational phytotherapy

Herbalism contrasts with rational phytotherapy in several ways (Table 13.2). Importantly, the herbalist’s approach has not been evaluated in controlled clinical trials, whereas there are numerous controlled clinical trials of specific phytotherapeutic preparations. Another important difference is that, although many of the same medicinal plants are used in each of the two approaches, the formulations of those herbs are often very different. For example, St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.) is used in both rational phytotherapy and by herbalists. However, in rational phytotherapy, the preparations used are likely to be extracts of H. perforatum herb (leaves and tops) standardized on hypericin content and formulated as tablets. By contrast, herbalists are likely to use a tincture of H. perforatum herb that is not standardized on its content of any particular constituent.

Table 13.2 Comparison of herbalism and rational phytotherapy

| Herbalism | Rational phytotherapy |

|---|---|

| Assumes that synergy or additive effects occur between herbal constituents or between herbs Holistic (individualistic) prescribing of herbs Preparations mainly formulated as tinctures Mainly uses combinations of herbs Some opposition towards tight standardization of preparations Not scientifically evaluated |

Seeks evidence that synergy or additive effects occur between herbal constituents or between herbs Not holistic; uses symptom- or condition-based prescribing Preparations mainly formulated as tablets and capsules Single-herb products used mainly Aims at using standardized extracts of plants or plant parts Science-based approach |

Homoeopathy

History

1. A substance which, used in large doses, causes a symptom(s) in a healthy person can be used to treat that symptom(s) in a person who is ill. For example, Coffea, a remedy prepared from the coffee bean (a constituent, caffeine, is a central nervous system stimulant) would be used to treat insomnia. This is the so-called ‘like cures like’ concept (in Latin, similia similibus curentur).

2. The minimal dose of the substance should be used in order to prevent toxicity. Initially, Hahnemann used high doses of substances, but this often led to toxic effects. Subsequently, substances were diluted in a stepwise manner and subjected to vigorous shaking (‘succussion’) at each step. This process is called potentization. It is claimed that the more dilute the remedy, the more potent it is. This completely opposes current scientific knowledge.

3. Only a single remedy or substance should be used in a patient at any one time.

Modern homoeopathy

In addition to the key principles of homoeopathy outlined above, homoeopaths also claim:

• illness results from the body’s inability to cope with challenging factors such as poor diet and adverse environmental conditions

• the signs and symptoms of disease represent the body’s attempt to restore order

• homoeopathic remedies work by stimulating the body’s own healing activity (the ‘vital force’) rather than by acting directly on the disease process

• the ‘vital force’ is expressed differently in each individual, so treatment must be chosen on an individual basis and thus needs to be holistic

Homoeopathic remedies

• Homoeopathic remedies are (mostly) highly dilute whereas herbal medicines are used at material strengths. However, since homeopathic preparations are first extracted from, for example, plant material and then diluted, there is a borderline group including mother tinctures and lower potencies (i.e. less diluted) which still may contain biomedically relevant amounts of active ingredients.

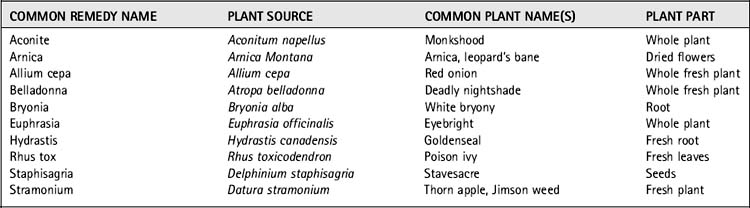

• Many homoeopathic remedies (around 65%) originate from plants, whereas by definition all herbal medicines originate from plants (for examples of plant-based homeopathic preparations see Table 13.3).

Evidence of efficacy

Homoeopathic treatment has been investigated in over 100 clinical trials, and the results of these studies have been subject to systematic review and meta-analysis. A meta-analysis of data from 89 placebo-controlled trials of homoeopathy indicated that the effects of homoeopathy are not completely due to placebo. Restricting the analysis to high-quality trials only reduced, but did not eliminate, the effect found. However, there was insufficient evidence to demonstrate that homoeopathy is clearly efficacious in any single clinical condition (Linde et al 1997). Many trials, particularly those with negative results for homoeopathy, have been criticized by proponents of homoeopathy because participants received the same homoeopathic treatment rather than individualized treatment. So, another meta-analysis considered all placebo-controlled trials (n= 19) of ‘individualized’ homoeopathy (i.e. where patients are prescribed the remedy most appropriate for their particular symptoms and personal characteristics; Linde and Melchart 1998). The study found that individualized homoeopathy was significantly more effective than placebo, but, when the methodologically best trials only were considered, no effect over that of placebo was seen for homoeopathy. Further work has provided strong evidence that, in homoeopathy, clinical trials of better methodological quality tend to yield less positive results. There have been several high-quality trials published since Linde et al’s original meta-analysis which report negative results, and it seems likely that the original meta-analysis ‘at least overestimated the effects of homeopathic treatments’ (Linde et al 1999).

Anthroposophical medicine

History

And he considered the human-being to be made of three functional systems:

• The ‘sense-nervous’ system (the head and spinal column), focusing on ‘cooling’ and ‘hardening’ processes (e.g. the development of arthritis).

• The ‘reproductive-metabolic’ system, which includes parts of the body that are in constant motion (e.g. the limbs and digestive system) and which focuses on warming and softening processes (e.g. fevers).

• The ‘rhythmic’ system (the heart, lungs and circulation), which balances the other two systems. Steiner believed that health is maintained by harmonious interaction of the three systems, and that cacophonous (inharmonious) interactions between the systems result in illness.

Aromatherapy

History

Aromatic plants and their extracts have been used in cosmetics and perfumes and for religious purposes for thousands of years, although the link with the therapeutic use of essential oils is weak. One of the foundations of aromatherapy is attributed to Rene-Maurice Gattefosse, a French perfumer chemist, who first used the term aromatherapy in 1928 (Vickers 1996). Gattefosse burnt his hand while working in a laboratory and found that lavender oil helped the burn to heal quickly with little scarring. Jean Valnet developed Gattefosse’s ideas of the benefits of essential oils in wound healing, and used essential oils more widely in specific medical disorders. Marguerite Maury popularized the ancient uses of essential oils for health, beauty and wellbeing and so played a role in the modern renaissance of aromatherapy.

Modern aromatherapy

• Aromatherapists believe that essential oils can be used not only for the treatment and prevention of disease, but also for their effects on mood, emotion and wellbeing.

• Aromatherapy is claimed to be an holistic therapy: an essential oil, or a combination of essential oils, is selected to suit each client’s symptoms, personality and emotional state, and treatment may change at subsequent visits.

• Essential oils are described both with reference to reputed pharmacological properties (e.g. antibacterial, anti-inflammatory) and to concepts not recognized in conventional medicine (e.g. ‘balancing’, ‘energizing’). There is often little agreement among aromatherapists on the ‘properties’ of specific essential oils.

• Aromatherapists claim that the constituents of essential oils, or combinations of oils, work synergistically to improve efficacy or to reduce the occurrence of adverse effects (described as ‘quenching’) associated with particular (e.g. irritant) constituents.

Conditions treated

Aromatherapy is widely used as an approach to relieving stress, and many essential oils are claimed to be ‘relaxing’. Many aromatherapists also claim that essential oils can be used in the treatment of a wide range of conditions. Often, many different properties and indications are listed for each essential oil, and conditions range from those that are relatively minor to those considered serious. For example, indications for peppermint leaf oil (Mentha × piperita) listed by one text include flatulence, ringworm, skin rashes, cystitis, indigestion, nausea, gastritis and sciatica, as well as migraine, hepatitis, jaundice, cirrhosis, bronchial asthma and impotence (Price & Price 1995). Many users self-administer essential oils either as a beauty treatment, as an aid to relaxation, or to treat specific ailments, many of which may not be suitable for self-treatment. Aromatherapy is also used in a variety of conventional healthcare settings, such as in palliative care, intensive care units, mental health units and in specialized units caring for patients with HIV/AIDS, physical disabilities and severe learning disabilities.

Essential oils

Essential oils should be referred to by the Latin binomial name of the plant species from which a particular oil is derived. The plant part used should be specified and, sometimes, further specification is necessary to define the chemotype of a particular plant; for example, Thymus vulgaris CT thymol describes a chemotype of a species of thyme that has thymol as a major chemical constituent (Clarke 2002).

Efficacy and safety

Essential oils are believed to act both by exerting pharmacological effects following absorption into the circulation and via the effects of their odour on the olfactory system. There is evidence that essential oils are absorbed into the circulation after topical application (i.e. massage) and after inhalation, although amounts entering the circulation are likely to be very small (Vickers 1996).

Certain essential oils have been shown to have pharmacological effects in animal models and in in vitro studies, but there is little good-quality clinical research investigating the effects of essential oils and aromatherapy as practised by aromatherapists. Most of the clinical trials that have been conducted do not show that massage with essential oils is significantly better than massage with carrier oil alone (Barnes 1998b). There is evidence that tea tree oil applied topically is effective in the treatment of certain skin infections, but these studies have not tested aromatherapy as practised by aromatherapists.

Flower remedy therapy

Flower remedies

• Gentian (Gentiana amarella) for despondency

• Holly (Ilex aquifolium) for jealousy

• Impatiens (Impatiens glandulifera) for impatience

Bach flower remedies are prepared from mother tinctures which are themselves made from plant material and natural spring water using either an infusion (‘sun’) method or a ‘boiling’ method (Kayne 2002). The infusion method is used to prepare mother tinctures for 20 of the Bach remedies: flower heads from the appropriate plant are added to a glass vessel containing natural spring water and are left to stand in direct sunlight for several hours, after which the flowers are discarded and the infused spring water retained. The boiling method involves the addition of plant material to natural spring water, which is then boiled for 30 minutes, cooled and strained. With both methods, the resulting solution is diluted with an equivalent volume of alcohol (brandy) to make the mother tincture. Flower remedies are then prepared by adding two drops of the appropriate mother tincture to 30 ml of grape alcohol. It is claimed that the resulting solution is equivalent to a 1 in 100,000 dilution. This is the same dilution as a 5X potency in homoeopathy, but preparation of flower remedies does not involve serial dilution and succussion. Thus, in material terms, flower remedies and 5X potencies can be considered equal, although from a homoeopathic perspective they are not.

Barnes J. Homoeopathy. Pharmaceutical Journal. 1998;260:492-497.

Barnes J. Aromatherapy. Pharmaceutical Journal. 1998;260:862-867.

Barnes J. Complementary medicine. Other therapies. Pharmaceutical Journal. 1998;261:490-493.

Clarke S. Essential chemistry for safe aromatherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2002.

Kayne S.B. Complementary therapies for pharmacists. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2002.

Linde K., Clausius N., Ramirez G., et al. Are the clinical effects of homeopathy placebo effects? A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Lancet. 1997;350(9081):834-843.

Linde K., Melchart D. Randomized controlled trials of individualized homeopathy: a state-of-the-art review. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 1998;4(4):371-388.

Linde K., Scholz M., Ramirez G., et al. Impact of study quality on outcome in placebo-controlled trials of homeopathy. J. Clin. Epidemiol.. 1999;52(7):631-636.

Price S., Price L. Aromatherapy for health professionals. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

Vickers A. Massage and aromatherapy. A guide for health professionals. London: Chapman & Hall; 1996.

Astin J.A. Why patients use alternative medicine. Results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279:1548-1553.

Barnes J., Ernst E. Traditional herbalists’ prescriptions for common clinical conditions: a survey of members of the National Institute of Medical Herbalists. Phytother. Res.. 1998;12:369-371.

Bellavite P., Ortolani R., Pontarollo F., Piasere V., Benato G., Conforti A. Immunology and homeopathy. 4. Clinical Studies—Part 1 eCAM. 2006;3:293-301.

Commission of the European Communities. Proposal for amending the directive 2001/83/EC as regards traditional herbal medicinal products. Brussels: European Commission; 2002. 2002/0008

Dantas F., Rampes H. Do homeopathic medicines provoke adverse effects? A systematic review. Br. Homeopath. J.. 2000;89(Suppl. 1):S35-S38.

Department of Health. Government response to the House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology’s report on complementary and alternative medicine. London: The Stationery Office; 2001.

Eldin S., Dunford A. Herbal medicine in primary care. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1999.

Evans W.C., editor. Trease and Evans pharmacognosy, sixteenth ed, Edingburgh: Saunders Ltd., (Elsevier), 2009.

Fulder S. The handbook of alternative and complementary medicine, third ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996.

Giovannini P., Schmidt K., Canterb P.H., Ernst E. Research into complementary and alternative medicine across Europe and the United States. Forsch. Komplementärmed. Klass. Naturheilkd.. 2004;11:224-230.

House of Lords Select Committee on Science and Technology. Complementary and alternative medicine. Session 1999–2000, 6th report. London: The Stationery Office, 2000.

Ipsos MORI. Public Perceptions of Herbal Medicines. London: General Public Qualitative & Quantitative Research. Ipsos Mori & MHRA; 2008.

Kayne S. Homoeopathic pharmacy. An introduction and handbook. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

Kennedy J., Wang C.C., Wu C.H. Patient disclosure about herb and supplement use among adults in the US. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med.. 2008;5:451-456.

Mills S.Y., Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

Sandhu D.S., Heinrich M. The use of health foods, spices and other botanicals with the Sikh community in London. Phytother. Res.. 2005;19:633-642.

Tisserand R., Balacs T. Essential oil safety. A guide for health professionals. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

Williamson E.M., Driver S., Baxter K., editors. Stockley’s herbal medicines interactions. London: Pharmaceutical Press, 2009.