chapter 16 Communicating with patients

THE PATIENT-CENTRED APPROACH

At around the same time that ‘The Progress of Medicine’ (see overleaf) was created, a number of clinicians began expressing similar concerns about the increasing disease-focus of modern medicine, and the corresponding decrease in attention to the patient as an individual. They began to articulate a different approach, one that did not ignore the great gains made in the scientific understanding, diagnosis and management of disease, but advocated an integration of all these advances with the individual patient’s experiences, beliefs, feelings, fears and expectations.1–3 They differentiated between disease and illness, disease being the ‘biological processes physicians use as an explanatory model for illness’,2 and illness being the patient’s experience of that physical or psychological disturbance.3,4 The disease describes the common features between patients with a particular disorder, and is therefore invaluable in establishing the pattern recognition required for effective diagnosis, prognostic predictions and treatment. However, the illness experience of each patient is unique, and encompasses the ‘real life’ complexity of the disorder, which often does not fit neatly into textbook descriptions or investigation results. Disregarding the illness can lead to the depersonalisation of medicine, and a disconnection between doctor and patient, with no shared understanding of the very nature of the problem, and the intent and aim of treatment.5 Medical historian Brian Hodges identifies a paradox: that by the middle of the twentieth century, when doctors were more able to offer hope of effective treatment, and even cure, than at any other time in history, patients were losing confidence in ‘traditional medicine’.6 This is not necessarily contradictory, if one considers that these scientific advances and the resultant increasing ability of doctors to effectively intervene shifted the focus to disease, with a gradual, inadvertent lessening in attention on and even respect for the illness experience. This is not to say that these doctors were uncaring, just that there was a mismatch between what patients were seeking and what doctors understood they were being asked to provide.

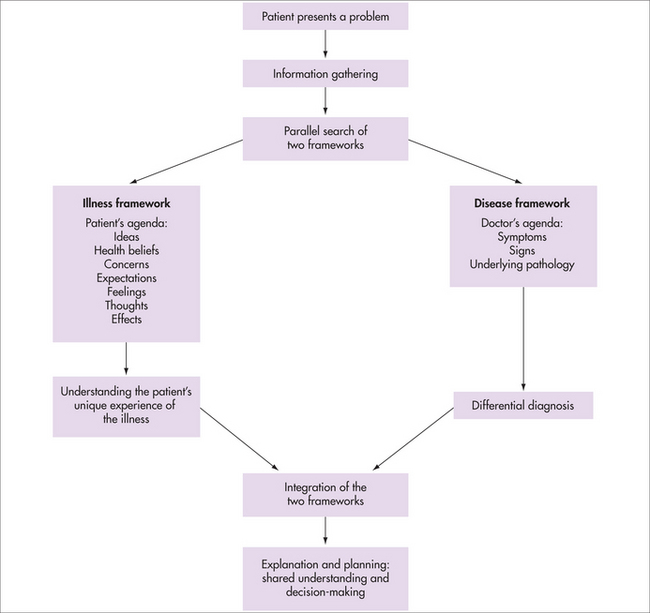

As general practitioners, we are often witness to the discordance between a patient’s complaint that a doctor did not listen or seemed uninterested and the comprehensive history and differential diagnoses detailed in the correspondence back to us. Usually this discordance represents a disease-focused consultation—the doctor has heard the parts of the story that fit the disease model, but has had selective deafness to the patient’s experiences that lie outside this construct or, at least, has not reflected back to the patient that they have heard and understood. Often these are the aspects of the story that are of most importance to the patient—the effect of the illness on their life, their fears, their struggles to make sense of the illness, its causation and prognosis. Of course, GPs are also susceptible to this ‘selective deafness’. The integration of both the disease and the illness experience improves our understanding of the disorder, and the patient, and subsequently our management options (see Fig 16.1). Hippocrates himself stressed the importance of considering both ‘what is common to every and particular to each case’.2

Initially described as the disease–illness model, the clinical approach outlined in Figure 16.1 became the foundation of patient-centredness, to contrast with a disease-centred approach. It grew out of real clinical experience in general practice / family medicine, rather than being developed in theoretical and academic circles and, as such, resonated with GPs and their clinical experiences. It now has a broader currency within other medical specialties, although some find the term ‘patient-centredness’ quite threatening, as it is wrongly assumed that its opposite is ‘doctor-centredness’, with the inference that a choice has to made between the doctor’s and the patient’s agendas, therefore implying that patient-centredness is akin to consumerist medicine rather than a relationship based on mutuality8 and a collaborative partnership.7 Patient-centredness does not mean ‘giving in’ to the patient: an overt exploration of the patient’s agenda allows an open discussion of their expectations, and a clear explanation for refusal, if required.

A key component of patient-centredness is to negotiate a balance between physician authority and patient autonomy, to achieve an optimal outcome for all involved. In some consultations, such as those involving health promotion or motivational interviewing, the scales will tip more towards patient autonomy. In other consultations the doctor may need to take on more of the decision-making responsibility. An extreme example of this would be in an emergency situation, or when the patient’s decision-making capacity is impaired. Recognising patient autonomy does not mean handing over all responsibility for decision-making to the patient, but using both doctor and patient expertise to inform the process. While the doctor brings their medical expertise to the consultation, patients are experts on themselves, with invaluable insights and knowledge of their own health status. In fact, patients’ self-assessments of their health have been shown to be a more accurate predictor of their survival, in both the short term and the long term, than more ‘objective’ measures from physical examination or a wide range of investigations.8

Most doctors have a preferred position on the spectrum between total patient autonomy and total physician authority, and tend to attract patients, where there is choice, who match this position. Although not all patients want to be actively involved in decision-making, most want to understand the options and the reasoning behind decisions.9 This interplay of roles potentially fluctuates with every consultation, not just with individual patient characteristics, but also with the same patient, depending on the nature and stage of the illness and the available management options acceptable to both parties. The truly patient-centred practitioner needs to be flexible enough to modify their approach accordingly.

McWhinney thus described two of the major tasks of the consultation to be to understand both the disease and the illness, and to integrate both the doctor’s and the patient’s agendas.2 The patient’s beliefs, concerns, expectations and preferences are actively sought and openly addressed, and the doctor’s reasoning in considering these made clear. Discordance between the doctor’s and the patient’s explanatory understandings of illness leads to misunderstanding and poor outcomes.2 One only has to consider three common examples to recognise the potential for dissonance: the cultural differences in health beliefs and health-seeking behaviours; the increased general acceptance of alternative and complementary therapies, many of which have significantly different underlying explanatory models; and the use by patients of information of variable quality accessed from the internet. A patient-centred approach leads to a greater understanding of the patient’s reasons for seeking help, and addressing of the patient’s specific concerns.7 This approach is associated with higher patient satisfaction and compliance than if their agenda was never explored, and with a significant improvement in clinical outcomes.4,5,7,8,10–13 Clinical competence also, not surprisingly, leads to patient satisfaction, although some studies have suggested that patients are unable to objectively assess technical competence except in glaring examples, and tend to infer it from the doctor’s interpersonal skills. Paling suggests that patient trust is a function of perceived competence and caring.14

Incorporating the patient’s agenda also has positive outcomes for doctors, such as more accurate, effective and efficient consultations, increased doctor satisfaction and decreased frustration.5,7,13 A patient-centred approach has been shown to positively correlate with such clinical measures as taking a reliable history, prescribing the correct medications and giving appropriate information.8

The concern of many doctors is that a patient-centred approach will mean longer consultations. Numerous studies have demonstrated little or no increase in the length of consultations,4,5,7,8,11 especially once practitioners have become adept in the skills. This is attributed to the improved efficiency of ascertaining, and therefore addressing, the patient’s agenda early in the consultation, and realistically establishing what can be achieved in the time available, which may include negotiating what would be better left to a future consultation. Levinson suggests that patients may feel subjectively that they have had enough time if there has been effective communication, rather than the consultation actually running longer.12 McWhinney proposed that even a longer consultation may be an effective investment of time in the long term, if it more accurately establishes the nature of the problem and mutually acceptable action plans, compared with a series of consultations where both doctor and patient struggle to establish shared understanding and common ground.2 Effective communication has been shown to decrease the need for follow-up appointments, as well as leading to fewer investigations and fewer referrals.7

An overt discussion of the two agendas, including the reasoning that underlies them, can help overcome an apparent conundrum in modern medicine. A solid body of research and literature supports a collaborative decision-making approach that respects patient autonomy. However, many doctors feel very exposed by the medico-legal implications of a patient taking a decision that subsequently leads to a negative outcome, for example by not following through a referral or investigation request. Identification of the patient’s agenda helps the doctor identify any discordance, and enables them to frame the consultation around the patient’s needs. Sharing the doctor’s thoughts involves the patient in problem solving, helps patients understand why the doctor is asking a particular question, performing a particular test or examination, or making a referral, and provides an opportunity for elaboration and clarification. When the doctor’s hypothesis forming and testing occurs internally, patients may not be able to distinguish between a suggestion, which they may choose to follow or not, and an imperative, or appreciate the intended urgency.

Poor doctor–patient communication is a leading factor in 70% of litigation, particularly when patients feel deserted, that their views are devalued or not understood, or that the information they receive is delivered poorly.12,15 Doctors who explicitly negotiate the structure and expectations of the consultation with their patients are less likely to be sued.7

The process of negotiating an integration of both agendas can help develop a stronger doctor–patient relationship, which can be therapeutic in itself.8 It conveys the doctor’s interest and respect for the individual patient, and enables the patient to ‘tell their story’, which is a fundamental human need, particularly at a time of anxiety and uncertainty such as when confronting illness.8 As well as being cathartic, in finding the words to describe their situation to the doctor, the patient can make more sense of it themselves, and perhaps develop insights and new awareness.8 Stories change in the telling, greatly influenced by the responses of the audience, and in this way we help shape—consciously or unconsciously, for better or worse—the patient’s understanding of their illness experience.

McWhinney stated that the greatest single problem in clinical interviewing is the failure to let the patient tell their story.2 In a frequently cited 1984 study, Beckman and Frankel demonstrated that in only 23% of consultations was the patient able to complete their response to the opening question, and that most doctors interrupted after 15–18 seconds.16 The longest any patient took to complete their story uninterrupted was 2½ minutes, with most completed by 45 seconds. Of particular note was the observation that the patients’ most clinically significant concerns were often raised later in their story—they ‘built up’ to them, often establishing the context initially. Directing the consultation to the earliest issues will mean that these other, more significant concerns will either not be raised at all, or raised much later in a consultation that has already been spent on less important or urgent issues. This leads to poor time management and both patient and doctor frustration.8 Of course, trying to establish all the patient’s agenda at the outset is not fail-safe, and many patients need time to develop the relationship, trust and confidence through the consultation to raise their most significant concerns, particularly if they are embarrassed or fearful.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS

Silverman and colleagues assert that the four essential components of clinical competence are knowledge, skills in communication, physical examination and problem solving.5,7 Communication skills are important not just for the interpersonal aspects of our work, but equally for the ‘technical’ tasks.8 Medical knowledge, physical examination and problem-solving skills are only useful if we can apply them, and for this we need to be able to take a relevant history, explain the reasons for examinations and investigations and ensure that the patient is giving informed consent, elucidate our diagnoses and management, and share our conclusions. This includes communication with our colleagues and other members of the healthcare team.

Effective communication is a clinical skill that can be learned.2,4,5,7,8,17 Communication skills do not depend on personality traits, and are not just about being ‘nice’ to patients. Certainly, they can be misused if the intent is not in the patient’s best interest and based on respect and positive regard. Although with practice they will become almost second nature, their use is still deliberate, and their selection based on the desired outcome. Until the doctor is practised and adept, they might feel forced, and sometimes their use will not be smooth; however, patients will usually still respond to the underlying intent, and forgive the occasional rough spot or back-tracking.

Different skills are usually required at different stages of the consultation, and this provides a useful structure for discussing them. Silverman and colleagues7 provide a detailed description of the structure of a typical medical consultation that incorporates a patient-centred approach, and identify the main tasks of each stage. Box 16.1 provides a summary of their framework.

BOX 16.1 Silverman et al’s expanded framework of the consultation

Source: Silverman et al. 19987

In reality, these stages merge, and some may not even be necessary in every consultation. If this is a repeat consultation with a patient, there will already be some existing rapport developed in earlier consultations, and instead there will be a reconnection—often through brief social conversation. Sometimes the reason for attendance is obvious—an acute injury, for example—or it may have been initiated by the doctor as a follow-up. Nevertheless, even if the reason is apparent, it is worth checking whether there are other concerns as well. An explanation may not be necessary in every consultation for a chronic illness, but it is still important to check that both the patient and the doctor have a shared understanding, especially as the illness changes over time, or complications arise. Building the relationship takes place throughout the consultation, and the skills used for maximal effectiveness in the other stages also foster a positive doctor–patient relationship.

INITIATING THE SESSION AND GATHERING INFORMATION

Clinical studies consistently show that the patient’s history contributes 60–80% of the information needed to make a diagnosis, even with all the technological advances in investigations. We have already discussed the importance of gathering information about the patient’s experience and agenda and establishing the doctor–patient relationship. Information is also gathered by physical examination and investigations, of course, and communication skills are vital here to explain to the patient what is intended, and why, to obtain informed consent, to ease anxiety, and to ensure patient engagement.14 This is an area where misunderstandings are too frequent and often lead to complaints against the doctor.

Listening

Effective listening includes paying attention to the non-verbal communication and the emotional content as well as the verbal content. Patient satisfaction is linked to the doctor’s skills in accurately interpreting emotions conveyed by body language.8 Yet body language can be culturally specific. Culture is not just related to ethnicity, but also includes sub-cultural characteristics such as those based on age, sex, education, socioeconomic status and occupation. The medical profession itself is a sub-cultural group with its own shared beliefs and assumptions.

Responding

Attending skills

Following skills

Questioning skills

Open-ended questions give the patient a broad scope in the area they wish to cover in their reply, and encourage elaboration. Examples are: ‘What can I do for you today?’, ‘Can you tell me more about yourself?’ Patients’ responses to open-ended questions reveal significantly more relevant information than their responses to closed questions.8

Closed questions invite a one-word answer—usually ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or a numerical answer. Because they tend to shut down elaboration by the patient and convey high control by the questioner, they can feel interrogatory unless ‘signposted’ or introduced. For example: ‘There are a few symptoms I need to check out specifically to help me work out the likely cause of your pain. Does the pain move into your neck? … Your arm? … Do you have any nausea? … Any shortness of breath or feeling puffed out? …’

There are two further question styles that are not usually helpful, and are better avoided.

To counteract traditional training there has been a move to encourage the greater use of open-ended questions. This is not to imply, however, that open-ended questions are intrinsically ‘better’ than closed or focused questions. Open, focused and closed questions all have their place, depending on the outcome one is seeking. For example, very talkative or disorganised patients can benefit from the structure provided to the consultation by focused or closed questions. Silverman and colleagues conceptualise the typical medical consultation as an ‘open-to-closed cone’,7 describing the progression of the questioning style, as the doctor enables the patient to tell their story initially, then ‘fills in the gaps’ with increasingly focused questions. Question styles are part of a continuum rather than discrete, different categories.

Reflecting skills

Doctor: ‘It sounds like your health has become a real concern now that you’re over 50.’

Advanced responding skills

‘You say you really don’t mind having to work late, and yet you sound quite angry about it.’

EXPLANATION AND PLANNING

This phase of the consultation typically refers to the task of explaining the doctor’s assessment and negotiating a mutually acceptable management plan, and therefore usually occurs in the second half of the consultation. However, it is important to remember the importance of planning the consultation itself, and explaining the rationale, which occurs much earlier. Doctors might see 30 or more patients a day in familiar surroundings, and it is easy for them to underestimate the uncertainty and anxiety about the consultation itself that many patients experience. Simple assumptions such as which aspects of the history are relevant, which examinations are indicated and the details of what the examinations involve can lead to misunderstandings. There are a number of specific techniques that are useful:7

The management phase

Studies have repeatedly shown that patients want more information from their doctors,6–8 and that the information they do receive does not match their needs. Doctors generally overestimate the amount of time they spend on explanation and information giving, and they tend to focus on treatment, especially drug treatment, whereas patients want information on diagnosis, causation and prognosis.6–8 Patients perceive doctors who provide clear, relevant and useful information as more personally caring, sincere and dedicated,8 but too often the information is incomprehensible to patients, being incomplete or full of technical terms, which adversely affects the patient’s understanding of their condition and its appropriate management.7

The doctor–patient relationship will affect how comfortable the patient feels in asking questions and seeking clarification. Patients are often concerned that the doctor will think badly of them if they ask too many questions—that they haven’t understood or are pushy, that they are questioning the doctor’s judgment or that they are taking too much of the busy doctor’s time.8 Perhaps not surprisingly, patients who ask questions receive more information7; ironically, however, those patients who have been involved throughout the consultation and shared in the doctor’s thoughts and rationale are likely to feel most comfortable and have the least need to seek clarification at this stage.

SUMMARY

In the medical consultation, effective communication:

Finally, it seems appropriate to give Ian McWhinney the last word.

Bolton R. People skills. How to assert yourself, listen to others and resolve conflicts. Sydney: Prentice Hall, 1986.

McWhinney IR. A textbook of family medicine. 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998.

1 Levenstein JH, McCracken EC, McWhinney IR, et al. The patient-centred clinical method. 1. A model for the doctor-patient interaction in family medicine. Fam Pract. 1986;3(1):24-30.

2 McWhinney IR. A textbook of family medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

3 Weston WW, Brown JB, Stewart MA. Patient-centred interviewing. Part I: Understanding patients’ experiences. Can Fam Physician. 1989;35:147-151.

4 Stewart M, Brown BB, Weston WW, et al. Patient-centred medicine. Transforming the clinical method. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1995.

5 Kurtz S, Silverman J, Draper J. Teaching and learning communication skills in medicine. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998.

6 Hodges B. The many and conflicting histories of medical education in Canada and the USA: an introduction to the paradigm wars. Med Educ. 2005;39:613-621.

7 Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J. Skills for communicating with patients. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1998.

8 Roter DL, Hall JA. Doctors talking with patients. Patients talking with doctors. Improving communication in medical visits. Westport, CN: Auburn House, 1992.

9 Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, et al. Shared decision-making not for all patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;54(12):531-535.

10 Horder J, Moore GT. The consultation and health outcomes. Br J Gen Prac. 1990;40(340):442-443.

11 Simpson M, Buckman R, Stewart M. Doctor–patient communication: the Toronto consensus. Br Med J. 1991;303:1385-1387.

12 Levinson W. Physician–patient communication: a key to malpractice prevention. JAMA. 1994;272(20):1619-1620.

13 Thiedke CC. What do we really know about patient satisfaction? Fam Pract Manage. 2007;14(1):33-36.

14 Paling J. Strategies to help patients understand risks. Br Med J. 2003;327:745-748.

15 Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, et al. The doctor–patient relationship and malpractice. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1365-1370.

16 Beckman HB, Frankel RM. The effect of physician behaviour on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:692-696.

17 Bolton R. People skills. How to assert yourself, listen to others and resolve conflicts. Sydney: Prentice Hall, 1986.

18 Robertson K. Active listening. More than just paying attention. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(12):1053-1055.

19 Mackay H. The good listener. Better relationships through better communication. Sydney: Pan Macmillan, 1994.

20 Kelly L. Listening to patients: a lifetime perspective from Ian McWhinney. Can J Rural Med. 1998;3:168-169.