Common Problems in Ambulatory Internal Medicine (Case 2: A Problem Set of Five Common Cases)

Madelaine R. Saldivar MD, MPH and M. Susan Burke MD

CASE 1

A 35-Year-Old Woman with Headache

The patient is a 35-year-old healthy woman who comes to the office with daily headache and dizziness for 6 weeks. Her only medication is an oral contraceptive. Her exam is unremarkable except for a blood pressure of 130/90 mm Hg and body mass index of 30.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Primary Headache |

Secondary Headache |

|

Migraine |

Medication side effect |

|

Tension |

Inflammatory: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), temporal arteritis |

|

|

Infectious: meningitis, sinusitis |

|

|

Intracranial mass or hemorrhage |

When we see this patient in the office, our first task is to determine whether she is well enough to continue her evaluation in the office. Signs and symptoms that warrant consideration for immediate transfer to the emergency department (ED) for emergent evaluation include sudden-onset severe headache, focal neurologic complaints, projectile vomiting, and severe hypertension. Headaches are common, and 90% of the time there will be a benign cause. A gradual onset of symptoms and a precipitating event, such as increased stress or a recent viral illness, make us consider benign causes.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• A careful history is the best tool to narrow the differential diagnosis.

• Radiologic studies are reserved for persistent or changed symptoms.

• Counseling on modifying environmental and lifestyle triggers is important.

History

Making sure there are no concerning symptoms is important. These are:

• Accompanying systemic symptoms

• Headache brought on by exertion

• Visual changes or focal neurologic deficits

• Sudden onset of the worst headache of one’s life

• Change in the pattern of chronic headache

Physical Examination

Tests for Consideration

|

$334 |

|

|

$534 |

|

|

$11 |

|

|

$12 |

|

|

$21 |

|

|

$272 |

|

|

$4 |

|

|

$16 |

|

|

$4 |

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Migraine Headache |

|

|

Pφ |

The pathophysiology of headaches is not well understood. However, experts agree that there are multiple factors that contribute to development of a headache: 1. Increased neuroexcitation with cortical spreading depression 2. Vascular dilation |

|

TP |

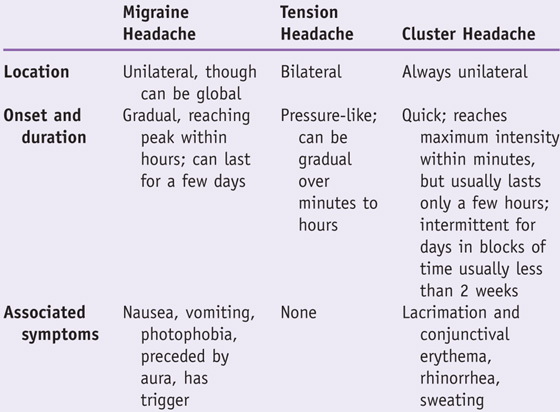

Migraine can be distinguished from other types of primary headaches by its characteristics. |

|

Dx |

Making the diagnosis is based on history and physical. Secondary causes and warning signs of more serious causes should not be present. |

|

Tx |

All of the headaches described above respond to acute management with analgesics. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen have been shown to be effective as first-line medications for tension and migraine headaches. Remove headache triggers—alcohol, chocolate, sweeteners, caffeine, nitrites, hormonal medications, stress, and schedule changes or sleep deprivation. If migraine headaches persist, consideration should be given to headache prophylaxis with daily suppressive therapy (e.g., amitriptyline, β-blocker, or topiramate). See Cecil Essentials 119. |

Secondary headaches are discussed in Chapter 64, Headache.

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache; report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology

Problem

What are evidence-based approaches to treating migraine headache?

Intervention

Analgesic medications and prophylactic medications

Quality of evidence

Systematic review of class I studies for treatment, class I, II, and III studies for diagnosis and neuroimaging utility

Outcome/effect

Migraine is a chronic condition with episodic attacks that affects 18% of women and 6% of men. Treat acute attacks rapidly. Consider prophylactic medications to reduce disability, frequency, and severity associated with attacks.

Historical significance

Migraine headaches are common and are disabling at a significant cost to society due to lost work productivity.

CASE 2

A 43-Year-Old Man with Back Pain

The patient is a 43-year-old truck driver who presents with right lower back pain (LBP) that started about a week ago when he lifted a heavy load at work. He stopped working and has been resting ever since. He tried acetaminophen, which did not help; however, his brother’s oxycodone with acetaminophen does provide him with relief.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Mechanical/nonspecific |

Disk herniation |

Compression fracture |

|

Degenerative spine disorders |

Spinal stenosis |

|

Speaking Intelligently

Back pain is the second most common symptom-related reason for which patients present to the doctor. The vast majority of low back pain is due to mechanical or nonspecific causes and does not require imaging. The goal of evaluation is to identify those patients needing urgent attention by looking for signs and symptoms (red flags) suggesting an underlying condition that may be more serious and by determining who may need urgent surgical evaluation. We also evaluate for psychosocial factors (yellow flags), because they are stronger predictors of LBP outcomes than either physical examination findings or severity and duration of pain.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

History

• Look for secondary gain, such as work disability and litigation.

• Evaluate for red flag symptoms that suggest more ominous causes requiring immediate evaluation.

• Recent significant trauma, mild trauma with age over 50 years

• Unexplained fever or recent urinary tract infection

• Prolonged use of glucocorticoids

• Progressive motor or sensory deficit

• Duration longer than 6 weeks

• Saddle anesthesia, bilateral sciatica/weakness, urinary or fecal difficulties

Physical Examination

• Observe patient walking and changing position.

• Check reflexes and sensation.

• Test for manual strength in both legs. Can the person walk on his or her heels (L5) and toes (S1)?

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Mechanical Low Back Pain/Nonspecific |

|

|

Pφ |

Complex and multifactorial; can involve any lumbar spine elements including bones, ligaments, tendons, disks, muscle, and nerve. Onset may be from an acute event or cumulative trauma. Most common presentation of back pain. May be divided into acute (<4 weeks), subacute (4–12 weeks), or chronic (>12 weeks). |

|

TP |

Pain can be hard for patient to localize because of the small cortical region dedicated to the back. |

|

Dx |

Clinical diagnosis; imaging is indicated only if red flags are present or symptoms persist. More than 90% of symptomatic lumbar disk herniations occur at the L4/L5 and L5/S1 levels. |

|

Tx |

Most mechanical LBP resolves within 6 weeks. If it persists or worsens (or both), consider imaging. For acute pain use heat, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), muscle relaxants, and/or spinal manipulation. For chronic pain, use exercise, heat, NSAIDs, tricyclic antidepressants, and/or spinal manipulation. May also consider acupuncture or cognitive behavioral therapy. See Cecil Essentials 119. |

|

Disk Herniation |

|

|

Pφ |

Herniation is thought to result from a defect in the annulus fibrosus, most likely due to excessive stress applied to the disk, with extrusion of material from the nucleus pulposus. Herniation most often occurs on the posterior or posterolateral aspect of the disk. |

|

TP |

Dermatomal distribution of sensory deficit, motor weakness, or hyporeflexia. |

|

Dx |

Clinical exam including SLR test. MRI is indicated only if weakness or incontinence is present. |

|

Tx |

Initial treatment is with analgesics and/or steroids. Surgery is reserved for patients with refractory pain or with evidence of motor deficits. Outcomes are similar at 5 years for patients treated either way. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

Authors

Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al., for the Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians/American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel

Institution

American College of Physicians

Reference

Ann Intern Med 2007;147:478–491

Problem

Back pain is common, but there is little consensus among the different specialties as to the appropriate clinical evaluation and management.

Intervention

To present the available evidence for evaluation and management of acute and chronic back pain

Quality of evidence

The literature search for this guideline included studies from Medline (1966 through November 2006), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and EMBASE.

Outcome/effect

Seven recommendations guide the clinician through the optimal approach to low back pain.

Historical significance/comments

The article provides joint recommendations from the ACP and APS.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Explore Underlying Reasons for Somatic Complaints

When a patient presents with multiple complaints, there are usually underlying social and psychological factors that should be explored. It is important to determine the patient’s insight regarding how these factors might be contributing to his or her problems. Express empathy and validate the decision to seek medical care. Reassure the patient that he or she does not have any life-threatening cause for the symptoms. Offering a patient a good balance of appropriate pharmacologic treatment and lifestyle modification is the best approach. Be clear that you will be following up with him or her in the near future.

Professionalism

Working in a busy outpatient clinic, physicians share the care of patients with many colleagues. There are times when the care that another physician provides raises concerns that the physician might be impaired. The American Medical Association defines an impaired physician as being unable to fulfill professional and personal responsibilities because of an alcohol or drug dependency, or a psychiatric illness. It is estimated that up to 15% of working physicians meet this criteria at some point during their careers, so it is reasonable to estimate that a considerable number of doctors have seen, or know firsthand, a colleague who may be impaired. Sometimes the impairment is clear: emotional lability, frequent absences, medical errors, and patient complaints. However, because doctors are high-performing individuals who are accustomed to masking stress and emotional issues while at work, impairment may be less obvious.

Physicians have an ethical obligation to report their suspicions of an impaired colleague who might be practicing under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or has a significant psychiatric impairment that is affecting patient safety. Such concerns should be reported to either the chief of service in the hospital or the state’s program for impaired physicians. Many physicians have difficulty following through on such reports, particularly when reporting involves a personal colleague. It is important to note, however, that many physicians, once reported, are able to keep their medical license and safely practice medicine again with proper counseling and rehabilitation.

Systems-Based Practice

Health Care Information Technology Can Enhance Patient Care

You have just seen your partner’s patient, who is complaining of neck pain, in the ED. You know that she has been treated for this before, but when she arrives in the ED on a Saturday, her file is in a cabinet in your locked office miles away. Paper-based medical records increase costs as a result of repeating laboratory tests and imaging studies, and increase the chance for errors. There is an enormous potential for information technology to impact the way in which we practice medicine. The ideal situation is to access this patient’s electronic health record (EHR) on a personal digital assistant (PDA), write inpatient orders wirelessly through the hospital’s computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system, and wirelessly transmit outpatient prescriptions to the patient’s pharmacy. Widespread adoption of these resources in the future will reduce unnecessary costs, decrease the likelihood of medical errors, and improve physician and patient satisfaction. As part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has released the final rule defining the term “meaningful use” of EHRs, which is a requirement that hospitals and medical professionals must meet to qualify for the Medicare and Medicaid incentives.

CASE 3

A 40-Year-Old Woman with Fatigue

The patient is a 40-year-old Greek woman who presents for lab results from a recent annual physical exam. Her only complaint was mild fatigue. Her lab tests were as follows:

Hemoglobin (Hgb) 10.0 (normal range 12.0–16.0 g/dL)

Hematocrit (Hct) 30.0% (normal range 35.0–47.0%)

Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 69 fL (normal range 83–92 fL)

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) 14% to 16% (normal range 11.1–14.5%)

Differential Diagnosis

|

Microcytic Anemia |

Normocytic Anemia |

Macrocytic Anemia |

|

Iron deficiency |

Chronic disease |

Vitamin B12 deficiency |

|

Chronic disease |

Chronic kidney disease |

Folate deficiency |

|

Thalassemia |

Acute blood loss |

Myelodysplasia |

|

Sideroblastic anemia |

Sickle cell anemia |

Bone marrow failure |

|

|

Hemolysis |

Hypothyroidism |

Speaking Intelligently

Anemia is a common finding in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients in the primary-care office. We always try to identify an underlying cause. In the United States iron deficiency is the predominant cause of anemia. We use the MCV (a measure of the average size of red blood cells) to categorize the anemia as microcytic, macrocytic, or normocytic. Based on this woman’s low MCV, concentrate on microcytic causes of anemia. Since she is only mildly symptomatic, she can be evaluated in the office. Symptoms that might prompt admission to the hospital would be hypotension, tachycardia, active bleeding, or decompensation of other comorbid illnesses, such as congestive heart failure or unstable angina.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Iron deficiency is the most common cause of microcytic anemia.

• It can be due to poor iron intake or chronic blood loss.

• The most sensitive test for iron deficiency is the serum ferritin, a measure of stored iron.

History

• With iron deficiency anemia, sources of blood loss can be identified with a good history.

Physical Examination

• Mild anemia (Hgb < 10 g/dL) usually is not associated with any physical findings.

• “Koilonychia,” or spooning of the nails, may also be present.

• Chronic blood loss is usually compensated even if the Hgb level is severely low.

Tests for Consideration

|

• Iron studies (serum iron, total iron-binding capacity [TIBC], and ferritin) |

$40 |

|

$6 |

|

|

$19 |

|

|

$5 |

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Iron Deficiency Anemia |

|

|

Pφ |

Iron deficiency anemia is caused by either decreased intake or absorption of iron, or loss of iron-containing red blood cells through hemolysis or bleeding. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage is a frequent pathologic cause of iron deficiency anemia; other causes are malabsorption syndromes and gastric bypass. |

|

TP |

In mild anemia, patients usually complain of fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance, and headaches. In more severe anemia, patients may have pica (a persistent desire to eat nonfood substances). |

|

Dx |

Low serum ferritin is the most sensitive marker for iron deficiency anemia. Since ferritin can be falsely elevated or normal due to acute inflammation, also measure the transferrin ratio, serum iron, or TIBC. In iron deficiency states, this ratio is low. Serum iron alone is a poor measure of iron stores. |

|

Tx |

Iron sulfate 325 mg three times a day is the treatment of choice. In patients with malabsorption problems, parenteral iron can be used. Hemoglobin levels should respond within several weeks. See Cecil Essentials 49. |

|

Anemia of Chronic Disease |

|

|

Pφ |

Patients with chronic inflammatory diseases have decreased secretion of erythropoietin and decreased responsiveness of erythroid precursors to erythropoietin. |

|

TP |

This is usually a laboratory finding seen in patients with chronic diseases, such as SLE, malignancy, congestive heart failure, and diabetes mellitus. |

|

Dx |

The typical iron study profile shows normal serum ferritin, low or normal serum iron, and low TIBC, resulting in normal transferrin saturation. |

|

Tx |

Treat the underlying inflammatory disorder. Since iron stores are normal, iron supplementation is not necessary. Erythropoietin may be used if erythropoietin levels are low for the degree of anemia found. See Cecil Essentials 49. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Anemia in adults: a contemporary approach to diagnosis

Historical significance

Provides a stepwise approach to the adult patient with anemia

CASE 4

A 29-Year-Old Man with a Rash

A 29-year-old man comes in with a rash on his wrist and elbow. He is healthy except for exercise-induced asthma and mild seasonal allergies. He says the rash is pruritic and started gradually. On exam, the rash is seen to be an erythematous and slightly raised plaque, and is located on the palmar surface of the wrist and the antecubital folds of the elbow. There are no satellite lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Eczema/atopic dermatitis |

Seborrheic dermatitis |

Contact dermatitis |

|

Nummular dermatitis |

Psoriasis |

Lichen simplex chronicus |

Speaking Intelligently

The first step is to determine if the rash is due to a primary dermatologic problem or is a sign of a systemic illness. Dermatitis is a rash related to a defect in the protective epidermal layer of the skin, characterized by pruritus and erythema, and lichenification in chronic cases. There are multiple forms of dermatitis, and these can be distinguished from one another by history and physical exam. It is important to distinguish between dermatitis and psoriasis, since psoriasis is more of a systemic inflammatory process that can have nonepidermal manifestations.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Dermatitis can be divided into various categories based on its history, appearance, and location.

• Psoriasis has a very strong hereditary component.

History

• Detailed personal history of exposures, medications, diet, diet changes

• Over-the-counter creams that have been used and failed

• Family history of atopy, asthma, psoriasis, inflammatory disorders

• History of psoriatic involvement of joints, gastrointestinal tract

• History of HIV risk factors or infection

Physical Examination

• Identify associated papules, pustules, or vesicles

• Note evidence of arthritis or nail changes (pitting) on exam

• Note if lymphadenopathy is present

Tests for Consideration

|

$6 |

|

|

$105 |

|

|

$13 |

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Atopic Dermatitis |

|

|

Pφ |

Usually starts in childhood but can persist into adulthood; a result of genetic predisposition and environmental factors. |

|

TP |

Pruritic, eczematous, poorly demarcated papulovesicular lesions located on wrists and on antecubital and popliteal fossae (flexor surfaces). Skin can become lichenified from chronic scratching. Excoriations are generally present. There is a general association with personal or family history of allergies, asthma, and allergic rhinitis. The history often includes sensitivity to certain products. |

|

Dx |

Clinical presentation is usually typical. IgE levels and peripheral eosinophilia are usually present. |

|

Tx |

Avoid exposure to irritating materials. Use emollients, such as hypoallergenic soap and lotion, daily. Mild- to moderate-potency steroids are effective. Antihistamines can help with pruritus. |

|

Seborrheic Dermatitis |

|

|

Pφ |

The cause is unclear, but the yeast Malassezia is implicated. Overgrowth causes a skin inflammatory response, resulting in seborrhea. |

|

TP |

Erythematous scaly plaques in areas with sebaceous glands such as the scalp, nasolabial folds, eyebrows, and upper trunk. These plaques are not intensely pruritic. Commonly associated with HIV. |

|

Dx |

Physical exam revealing the above distribution of plaques is enough to establish the diagnosis. |

|

Tx |

For scalp lesions, shampoos containing tar, selenium sulfide, and zinc pyrithione are usually effective. Since Malassezia fungal infection is implicated in the inflammatory response, use of antifungal shampoo may also be useful. For face and skin lesions, topical low-potency steroids and antifungal creams have been used with success. See Cecil Essentials 108. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Atopic and non-atopic eczema

Historical significance: clinical review

Discussion of the pathophysiology and genetic factors important in the development of eczema. Also discusses common treatments for eczema.

CASE 5

A 57-Year-Old Man with a Cough

A 57-year-old man with hypertension, coronary artery disease, and obesity presents with dry cough for 4 weeks. He notes the cough is worse at night but also occurs during the day. He still smokes cigarettes (¼ pack per day). He denies chest pain. He is compliant with his medications, including lisinopril, simvastatin, loratadine, and aspirin. On exam he has a few scattered wheezes but no rales or rhonchi. He is obese. His cardiac exam is normal.

Differential Diagnosis

|

Bronchopulmonary infection |

Congestive heart failure |

Allergic rhinitis/postnasal drip |

|

Asthma exacerbation |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) |

Head and neck cancer |

|

Lung cancer |

Speaking Intelligently

Take a detailed history, paying extra attention to the time frame of the cough. Acute infectious causes tend to resolve within 2 to 6 weeks, while more chronic causes will persist for months. Associated symptoms are very important, especially in the case of cardiac causes. Since this patient has a history of heart disease and ongoing risk factors, make sure to include an angina and heart failure history in questioning.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Keep in mind the patient’s risk factors and age.

History

Important red flags that should prompt early testing include:

• Cancer: weight loss, hemoptysis, voice changes, worsening dyspnea, dysphagia

Physical Examination

• Concentrate on the lung and head and neck exams.

• Do you hear wheezing, stridor?

• Is there cervical lymphadenopathy?

Tests for Consideration

|

• Chest radiography if infection is a concern or red flags are present |

$45 |

|

$52 |

|

|

$334 |

|

|

$600 |

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Asthma |

|

|

Pφ |

Immediate IgE-mediated bronchospasm followed by cell-mediated inflammatory response in prolonged symptoms and in chronic asthma. |

|

TP |

Presents with acute onset of shortness of breath and dyspnea; may be audibly wheezing. Tachypnea and difficulty completing sentences may precede respiratory failure. Clinical exam will reveal wheezing. |

|

Dx |

Chest radiograph is usually normal; peak expiratory flow rate and FEV1 are decreased. |

|

Tx |

Bronchodilators (albuterol, salmeterol); corticosteroids (inhaled and/or oral); immunomodulators (montelukast); other (theophylline). See Cecil Essentials 17. |

|

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

|

|

Pφ |

Hyperacidity in the distal esophagus due to abnormal relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. |

|

TP |

Heartburn symptoms; cough; association with certain foods, especially mint, spicy foods, fatty foods, alcohol. |

|

Dx |

Response to empirical treatment with antacid therapy; esophagogastroduodenoscopy can show typical inflammatory changes; probe of the lower esophageal area shows acidic pH. |

|

Tx |

Proton-pump inhibitor therapy; avoidance of foods that cause symptoms; weight loss; in severe cases, fundoplication surgery may be needed. See Cecil Essentials 36. |

|

Allergic Rhinitis |

|

|

Pφ |

IgE-mediated histamine release in response to environmental exposure. |

|

TP |

Postnasal drip with nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and cough. |

|

Dx |

Typical symptoms respond to antihistamine treatment; in severe cases allergy skin and radioallergosorbent testing (RAST) may be necessary. |

|

Tx |

Antihistamines; steroid nasal inhaler. See Cecil Essentials 98. |

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

The diagnosis and treatment of cough

Problem

What is the best approach to diagnosing cough?

Intervention

This is a discussion of common causes of cough and a stepwise approach to diagnosis and management, including suggested guidelines for treatment.

Outcome/effect

Using a systematic approach can lead to appropriate diagnosis and management of cough in 88% to 100% of cases while avoiding nonspecific therapy and costly diagnostic tests.

Interpersonal and Communications Skills

Prepare Patients for the Possibility of Further Testing

Before you begin the evaluation of a patient, it is important to communicate the potential need for more invasive testing depending on the results of initial studies. Prepare the patient to consider the possible need for further testing, as it is important to be sure that he or she will be willing to undergo future tests, such as colonoscopy or CT scanning, if an abnormality is identified. If patients are unsure about their willingness to comply with additional testing, empathize with their concerns, but assist them in understanding the rationale for your management plan.

Systems-Based Practice

Use Practice Guidelines in Medical Decision Making

Practice guidelines are a useful tool in helping to treat chronic diseases such as asthma and anemia. The best practice guidelines are based on evidence and are endorsed by expert panels consisting of representatives from stakeholder organizations. Guidelines can be found easily by performing a web-based search: http://www.guideline.gov. This is an excellent link to the National Guideline Warehouse assembled by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Institute of Medicine has proposed standards for a trustworthy guideline in which a guideline should (1) follow a transparent process; (2) be developed by a multidisciplinary panel; (3) use rigorous systematic evidence; (4) review and summarize evidence (and gaps) about potential benefits and harms of each recommendation; (5) provide a rating of the level of confidence in the evidence and the strength of each recommendation; (6) undergo extensive external review; and (7) have a mechanism for revision as new evidence becomes available.

Guideline standards from Laine C, Taichman DB, Mulrow C: Trustworthy Clinical Guidelines, Annals of Internal Medicine, June 7, 2011, vol. 154, no. 11, 774–775, Table 1. Used with permission from American College of Physicians.