Chapter 137 Combined Hamartoma of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium and Retina

Combined hamartomas of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (CHRRPE) are benign tumors that may cause significant visual loss depending upon location. Accurate diagnosis is essential because the lesion may resemble a choroidal melanoma or other intraocular tumor. Combined hamartomas are usually solitary, unilateral lesions located at the optic disc or posterior pole. They typically appear slightly elevated and have varying amounts of pigmentation, vascular tortuosity, and epiretinal membrane formation. A hamartoma is defined as a benign overgrowth of cells that are normally present. CHRRPE lesions are characterized by predominant tissue subtype, including pigment epithelial, vascular or glial.1

Historical review

Early reports on combined hamartomas describe lesions that were clinically mistaken for choroidal malignancy. Histopathologically, these lesions were described as hyperplastic retinal pigment epithelium and were located juxtapapillary, in the posterior pole or peripherally.2,3 In 1961, the term “hamartoma” was used to describe a large lesion of the posterior pole in a child.4 In 1973, Gass5 reported lesions in five children and two young adults, and used the term “combined hamartoma.” In 1984, Schachat et al.,1 described 60 patients with combined hamartomas in a collaborative effort of the Macula Society Research Committee. Gass6 reported an additional 35 patients in his discussion of the Macula Society’s report. Additionally, there have been more recent reports of combined hamartomas, including a review of visual acuity outcomes of 77 patients from a single institution.7

Epidemiology

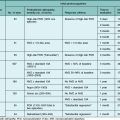

In the Macula Society’s report1 of 60 patients with combined hamartomas, the mean age at the time of diagnosis was 15 years, with a range of 10 months to 66 years. The number of males and females was equal, and three patients were black. In a recent report by Shields et al.7 which evaluated 77 patients with CHRRPE, the mean age of diagnosis was 11.9 months with a range of 0.4–60 months. There is no apparent predilection based on sex or race.

Clinical manifestations

Symptoms

Reviews of several large reports show that painless visual loss is the chief complaint in the majority of patients followed by strabismus, floaters, leukocoria and ocular pain. Detection during routine examination was reported in 10% of patients.1,7,8

Visual acuity

Visual function varies with the location of the lesion.7 Direct macular involvement including the optic nerve, papillomacular bundle, or fovea may reduce visual acuity. Extramacular lesions may cause visual loss from indirect macular distortion related to tractional forces. Other secondary causes of visual loss include choroidal neovascularization,1,9 vitreous hemorrhage,10,11 exudative retinal detachments,1 retinoschisis,1,12 and macular hole formation,13 although these are uncommon. In the Macula Society report,1 visual acuity was 20/40 or better in 45% of patients, and it was 20/200 or worse in 40%. In a review by Font et al.,8 28% were 20/40 or better, whereas 28% were worse than 20/200. A report by Shields et al.7 showed age, symptoms and visual acuity were related to tumor location. Compared with extramacular lesions, macular lesions were associated with younger presentation (mean age 14.2 months versus 9.5 months), strabismus (25 versus 31%) and decreased visual acuity (37% versus 43%) and visual acuity ≤20/200 (25% versus 69%). Mean visual acuity of macular and extramacular CHRRPE lesions was 20/320 and 20/80, respectively.

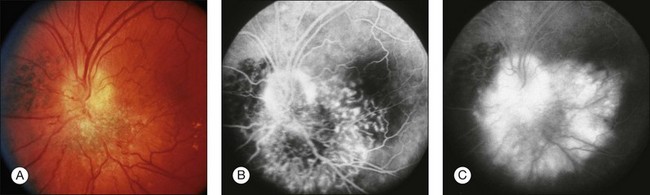

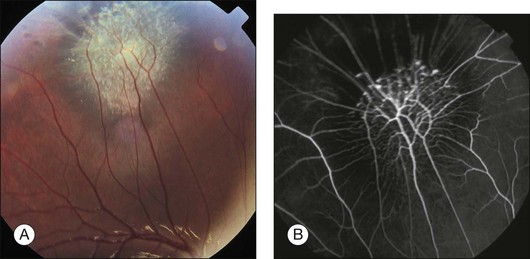

Ophthalmoscopic appearance

Combined hamartomas may be located on the optic disc and juxtapapillary region, in the macula, and in the mid-periphery. The ophthalmoscopic appearance varies depending on the location of the tumor. Lesions of the posterior pole have varying amounts of retinal pigment epithelial, vascular, and glial components, and one tumor type tends to predominate (Fig. 137.1). Clinical features include an elevated pigmented mass involving the RPE, retina and overlying vitreous with extension of fanlike projections towards the periphery. This lesion may blend imperceptibly with the surrounding RPE with an absence of RPE or choroidal atrophy. The lesion may be covered by a thickened gray-white retinal and preretinal tissue which may show contraction of the inner surface. There is generally absence of retinal detachment, hemorrhage, and vitreous inflammation.5 The Macula Society1 reported retinal vascular tortuosity within the lesion in 93% of patients, hyperpigmentation in 87%, slight elevation in 80%, epiretinal membrane formation in 78%, and exudation in 7%. Peripheral lesions14 appear as an elevated ridge concentric with the disc. Adjacent to the lesion, larger retinal vessels appear stretched, and there are few smaller vessels (Fig. 137.2). A dragged disc appearance has been described in patients with peripheral lesions.5,15 Combined hamartomas are almost always solitary, unilateral tumors; however, a few cases of bilateral involvement have been reported in association with neurofibromatosis.9,16–18

Associated ocular findings

Extensive disc or macular lesions may be associated with a relative afferent pupillary defect. Patients with macular involvement and decreased vision often have strabismus.7 Other findings include vitreous hemorrhage,10,11 preretinal neovascularization peripheral to the harmartoma,19 choroidal neovascularization at the margin of the lesion1,9,20 macular hole13 and peripheral hole formation.21 In addition, CHRRPE lesion have been associated with X-linked juvenile retinoschisis, optic nerve head pits, optic nerve colobomas and optic nerve head drusen.1,5,22

Systemic associations

Most patients with combined hamartomas do not have evidence of systemic disease; however, numerous reports describe an association with neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2.5,16–18,23–25 Bilateral CHRRPE lesions have been identified in patient with neurofibromatosis 1 and a majority of patients with bilateral combined hamartomas have signs of neurofibromatosis.9,16,18 In addition, CHRRPE lesions have been reported as a presenting sign in suspected neurofibromatosis. Of note, epiretinal membranes can also be present in patients with neurofibromatosis 2.25 Combined hamartomas have also been reported in patients with facial hemangiomas,5 incontinentia pigmenti,1 tuberous sclerosis,11 Gorlin Goltz syndrome,26 Poland anomaly,27 branchio-oculofacial syndrome,28 and juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.29

Diagnostic evaluation

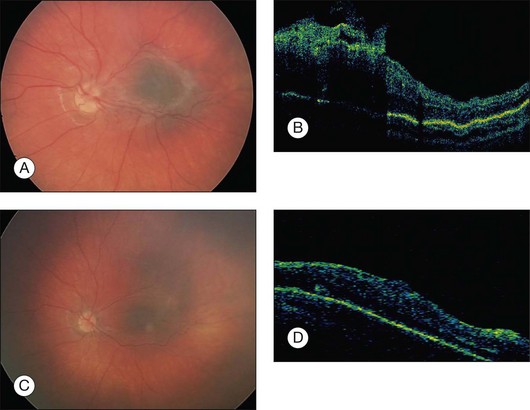

Optical coherence tomography is an important modality for diagnosing and characterizing CHRRPE lesions. Early generation OCT images demonstrated an elevated lesion with high reflectivity of the inner retina, hyporeflective shadowing of the underlying tissue, and obscuration of the normal retinal layers.30,31 High-resolution spectral domain OCT imaging shows characteristic findings, including: peaked vitreoretinal traction, retinal disorganization, thickening of the retina at the level of the RPE and preretinal vitreoretinal interface abnormalities.32 OCT imaging can delineate the transition between the abnormal retinal interface and can guide surgical intervention. OCT is an important tool used to aid in the differential diagnosis and management of CHRRPE lesions. Ultrasonography is not useful in diagnosis of these minimally elevated lesions.

Differential diagnosis

Epiretinal membrane

The most common differential diagnostic consideration is epiretinal membrane. As for epiretinal membranes, the vitreoretinal interface change is present as is vascular tortuosity. The hyperpigmentation associated with CHRRPE lesions is rarely present. Epiretinal membranes may show a “cellophane” light reflex or a thickened, opaque membrane with superficial retinal folds and traction lines. A review of 44 patients with childhood ERMs showed association with trauma or uveitis and are predominantly identified in males in the second decade of life.33 It may be extremely difficult to distinguish between epiretinal membranes and CHRRPE lesions in eyes with no known history of trauma or inflammation. OCT testing can be helpful for differentiating CHRRPE and epiretinal membranes. The intraretinal component of CHRRPE lesions, which is often difficult to discern by FA or clinical examination is evident with high-resolution OCT imaging.32 OCT imaging can also be useful for identifying and guiding surgical removal of preretinal vitreoretinal traction associated with CHRRPE lesions. Preretinal components of CHRRPE lesions can be removed surgically, but the adhesion between disorganized retinal structures and thickened RPE cannot be removed. For this reason, some measure of persistence of the CHRRPE lesion is routinely noted following surgery.

Pigmented choroidal lesions

Choroidal melanomas, choroidal nevi, congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE), adenoma and adenocarcinoma of the RPE can be misidentified as a CHRRPE lesion. Choroidal melanomas are subretinal, elevated and lack vitreoretinal interface changes and vascular tortuosity. Choroidal nevi lack vitreoretinal interface changes and vascular tortuosity as well. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium is subretinal as well, and flat with normal retinal vessels. Adenoma and adenocarcinoma of the retinal pigment epithelium are rare and usually jet-black in color.14

Clinical course

Visual loss in patients with combined hamartomas is associated with macular involvement. Distortion of retinal anatomy and disorganization of retinal components can cause strabismus and amblyopia in children. Visual loss has been associated with vitreous hemorrhage, choroidal neovascularization, macular edema, retinoschisis, peripheral and macular hole formation and retinal detachment.1,9–13,16,20,34 Peripheral lesions are generally asymptomatic, but vitreous traction may increase vascular tortuosity and result in macular distortion. In the Macula Society report,1 66% of patients maintained their visual acuity after 4 years, 24% of patients lost two or more lines, and 10% of patients improved by two or more lines as a result of amblyopia therapy or vitreous surgery. In the Macula Society report, the mean age was 15 years. A more recent report (mean age of 9.5 months) showed that 60% of patients with macular lesions and 13% of patients with extramacular lesions had a ≥3 line visual loss after 4 years of follow-up.7 The decline in visual outcome over 4 years in this study indicates the need for frequent evaluation, amblyopia therapy and possible surgical intervention. Unfortunately, data from population-based studies is not available to confirm progression or long-term stability of asymptomatic lesions.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Although combined hamartomas have not been reported to be present at birth, they have been noted in infants 2 weeks of age7 which supports a congenital etiology. The association of combined hamartomas with neurofibromatosis supports a developmental etiology. Some evidence exists that the lesion may occur as result of ocular inflammation.35–37 An additional report described an 8-year-old patient with a unilateral combined hamartoma who had developed a similar-appearing lesion with consequent visual loss in the fellow eye at a 2.5-year follow-up.17 Cytogenic analysis of a patient with a combined hamartoma revealed a chromosome 11;18 translocation.38

Histopathology

Combined hamartomas show marked disorganization of the retinal architecture with preretinal, intraretinal and subretinal components. Proliferation of glial tissue has been described as focal areas of gliosis in the nerve fiber layer associated with wrinkling of the internal limiting membrane.3 The retinal pigment epithelium proliferates as cords and sheets within the overlying inner retina and may exhibit a perivascular distribution. In juxtapapillary lesions, there may be proliferation of the retinal pigment epithelium into the optic disc.2 The peripapillary retina and optic nerve head may be thickened by increased numbers of blood vessels and by proliferated retinal pigment epithelium.39

Treatment

Medical

In patients with CHRRPE lesions, a functional component of amblyopia may be superimposed on visual loss caused by structural abnormalities, and in some cases, visual acuity has increased with amblyopia therapy.1,40 One report described progressive visual loss due to vascular leakage in the macula that was treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT). Following PDT, vascular closure was demonstrated with fluorescein angiography.41 Visual loss from subfoveal choroidal neovascularization has been demonstrated in CHRRPE lesions. Submacular surgery and removal of the choroidal neovascular membrane in one report improved vision from 20/60 to 20/20.42 Although there are no current reports describing treatment of CHRRPE-associated choroidal neovascular membranes with anti-VEGF agents, this modality could be potentially useful.

Surgical

As stated previously, the clinical course of macular CHRRPE lesions is progressive visual loss. In the Macula Society report,1 24% of patients lost two or more lines of vision after 4 years. A recent report examining younger patients (mean age of 9.5 months) showed that 60% of patients with macular lesions had a ≥3 line of visual loss after 4 years.7 The natural history of progressive visual loss shows the importance of monitoring and evaluation for surgical intervention. Lesions generally have one predominant tissue subtype, including melanocytic, vascular or glial. The glial subtype with prominent epiretinal membrane proliferation is most amenable to surgical intervention. Macular lesions related to progressive visual loss have shown vitreous traction that may be amenable to surgical treatment.43 OCT imaging is an invaluable tool for identifying vitreoretinal interface abnormalities and determining the presence of a surgical plane (Fig. 137.3).

Of 60 patients reviewed by the Macula Society report, three underwent surgery and only one had improvement of vision (20/200 to 20/40) while the other two showed no improvement.1 Other authors reported poor visual outcomes following removal of CHRRPE in two adult cases. Both patients had long-standing poor vision with amblyopia likely impacting their final visual outcome.44 Additional reports indicate improved surgical outcomes for CHRRPE lesions.45–50 The cases described in these reports show dense epiretinal membranes with a tight adherence of the posterior hyaloid that were removed with vitrectomy and membrane peeling. Visual improvement and improvement of macular architecture were observed. In addition, a combination of pars plana vitrectomy, membrane peeling, intravitreal triamcinolone and laser has been reported to reduce vascular activity and reduce traction associated with the abnormal vitreoretinal interface.51

A relatively large series of 11 pediatric patients (1–14 years old) with vitreoretinal interface abnormalities associated with CHRRPE lesions has been reported.43 Following surgical intervention, all of the patients demonstrated improved or stabilized vision. Surgical success was attributed to early surgical intervention by vitrectomy and membrane stripping to improve retinal architecture and lessen the affects of amblyopia. In this study, preoperative autologous plasmin enzyme was injected to assist in removing extensive vitreomacular traction and vitreoretinal proliferation.43 Autologous plasmin enzyme is a well-studied surgical adjunct that cleaves the vitreoretinal interface and induces a posterior vitreous detachment without damaging the underlying retina.52 In a study by Shields et al.,31 91% of patients with CHRRPE had preretinal membranes visible by OCT. The use of autologous plasmin can create a cleavage plane to facilitate epiretinal removal and reduce potential complications inherent to adherent posterior hyaloid.

1 Schachat AP, Shields JA, Fine SL, et al. Combined hamartomas of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1609–1615.

2 Theobald GD, Floyd G, Kirk HQ. Hyperplasia of the retinal pigment epithelium simulating a neoplasm: report of two cases. Am J Ophthalmol. 1958;45:235–240.

3 Vogel MH, Zimmermann LE, Gass JDM. Proliferation of the juxtapapillary retinal pigment epithelium simulating malignant melanoma. Doc Ophthalmol. 1969;26:461–481.

4 Cardell BS, Starbuck MJ. Juxtapapillary hamartoma of retina. Br J Ophthalmol. 1961;45:672–677.

5 Gass JD. An unusual hamartoma of the pigment epithelium and retina simulating choroidal melanoma and retinoblastoma. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1973;71:171–185.

6 Gass JD. Combined hamartomas of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1609–1615.

7 Shields CL, Thangappan A, Hartzell K, et al. Combined Hamartoma of the Retina and Retinal pigment Epithelium in 77 consecutive patients. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:2246–2252.

8 Font RL, Moura RA, Shetlar DJ, et al. Combined hamartoma of sensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Retina. 1989;9:302–311.

9 Flood TP, Orth DH, Aaberg TM, et al. Macular hamartomas of the retinal pigment epithelium and retina. Retina. 1983;3:164–170.

10 Kahn D, Goldberg MF, Jednock N. Combined retinal–retina pigment epithelial hamartoma presenting as a vitreous hemorrhage. Retina. 1984;4:40–43.

11 Wang CL, Brucker AJ. Vitreous hemorrhage secondary to juxtapapillary vascular hamartoma of the retina. Retina. 1984;4:44–47.

12 Schachat AP, Glaser MB. Retinal hamartoma, acquired retinoschisis and retinal hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:604–605.

13 Mason JO, III., Kleiner R. Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium associated with epiretinal membrane and macular hole. Retina. 1997;17:160–162.

14 Shields JA, Shields CL. Intraocular tumors. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992.

15 Harper CA, Gole GA. Combined hamartoma of the retina and RPE: an unusual case of the dragged disc appearance. Aust NZ J Ophthalmol. 1986;14:235–238.

16 Destro M, D’Amico DJ, Gragoudas ES, et al. Retinal manifestations of neurofibromatosis: diagnosis and management. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:662–666.

17 Meyer JH, Witschel H. Bilateral combined hamartoma of the retina and the retinal pigment epithelium. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:577–578.

18 Vianna RNG, Pacheco DF, Vasconcelos MM, et al. Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium associated with neurofibromatosis type-1. Int Ophthalmol. 2002;24:63–66.

19 Helbig H, Niederberger H. Presumed combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium with preretinal neovascularization. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:1157–1159.

20 Theodossiadis PG, Panagiotidis DN, Baltatzis SG, et al. Combined hamartoma of the sensory retina and retinal pigment epithelium involving the optic disk associated with choroidal neovascularization. Retina. 2001;21:267–270.

21 Verma L, Venkatesh P, Lakshmaiah CN, et al. Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium with full thickness retinal hole and without retinoschisis. Ophthalmol Surg Lasers. 2000;31:423–426.

22 Damasceno NA, Damasceno EF. Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium associated with optic coloboma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:353–354.

23 Cotlier E. Café-au-lait spots of the fundus in neurofibromatosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:1990–1992.

24 Sivalingam A, Augsburger J, Perilongo G, et al. Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 2. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1991;28:320–322.

25 Kaye LD, Rothner AD, Beauchamp GR, et al. Ocular findings associated with neurofibromatosis type II. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1424–1429.

26 DePotter P, Stanescu D, Caspers-Velu L, et al. Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium in Gorlin syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:1004–1005.

27 Stupp T, Pavlidis M, Bochner T, et al. Poland anomaly associated with ipsilateral combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Eye. 2004;18:550–552.

28 Demirci H, Shields CL, Shields JA. New ophthalmic manifestations of branchio-oculo-facial syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:362–364.

29 Fonseca RA, Dantas MA, Kaga T, et al. Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium associated with juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:131–132.

30 Ting TD, McCuen BW, II., Fekrat S. Combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium: optical coherence tomography. Retina. 2002;22:98–101.

31 Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Dai VV, et al. Optical coherence tomographic findings of combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium in 11 patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1746–1750.

32 Huot CS, Desai KB, Shah VB. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography of combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2009;40:322–324.

33 Khaja HA, McCannel CA, Diehl NN, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of epiretinal membranes in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:632–636.

34 Schachat AP, Glaser BM. Retinal hamartoma, acquired retinoschisis, and retinal hole. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;99:604–605.

35 Hrisomalos NF, Mansour AM, Jampol LM, et al. “Pseudo”-combined hamartoma following papilledema. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1634–1635.

36 Ticho BH, Egel RT, Jampol LM. Acquired combined hamartoma of the retina and pigment epithelium following parainfectious meningoencephalitis with optic neuritis. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1998;35:116–118.

37 Dark AJ, Richardson J, Howe JW. Retinal hamartoma in childhood. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1978;15:273–277.

38 Kutsche K, Glauner E, Knauf S, et al. Cloning and characterization of the breakpoint regions of a chromosome 11;18 translocation in a patient with hamartoma of the retinal pigment epithelium. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2000;91:141–147.

39 Green WR. Pathology of the retinal pigment epithelium. Spencer WD, ed. Ophthalmic pathology: an atlas and textbook, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1985.

40 Kushner BJ. Functional amblyopia associated with organic ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;91:39–45.

41 Cilliers H, Harper CA. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin for vascular leakage from a combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:186–188.

42 Inoue M, Noda K, Ishida S, et al. Successful treatment of subfoveal choroidal revascularization associated with combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:155–156.

43 Cohn AD, Quiram PA, Drenser KA, et al. Surgical outcomes of epiretinal membranes associated with combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Retina. 2009;29:825–830.

44 McDonald HR, Abrams GW, Burke JM, et al. Clinicopathologic results of vitreous surgery for epiretinal membranes in patients with combined retinal and retinal pigment epithelial hamartomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:806–813.

45 Sappenfield DL, Gitter KA. Surgical intervention for combined retinal–retinal pigment epithelial hamartoma. Retina. 1990;10:119–124.

46 Benhamou N, Massin P, Spolaore R, et al. Surgical management of epiretinal membrane in young patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:358–364.

47 Stallman JB. Visual improvement after pars plana vitrectomy and membrane peeling for vitreoretinal traction associated with combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Retina. 2002;22:101–104.

48 Xiao Z, Fangian D, Rongping D, et al. Surgical management of epiretinal membrane in combined hamartomas of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Retina. 2010;30:305–309.

49 Mason JO, III. Visual improvement after pars plana vitrectomy and membrane peeling for vitreoretinal traction associated with combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Retina. 2002;22:824–825.

50 Konstantinidis L, Chamot L, Zografos L, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy and epiretinal membrane peeling for vitreoretinal traction associated with combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (CHRRPE). Klin Monatsbl Augenheild. 2007;224:356–359.

51 Nam DH, Shin KH, Lee DY, et al. Vitrectomy, laser photocoagulation, and intravitreal triamcinolone for combined hamartoma of the retina and retinal pigment epithelium. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010;9:1–464.

52 Wu WC, Drenser KA, Trese MT, et al. Pediatric traumatic macular hole: results of autologous plasmin enzyme-assisted vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:668–672.