Colorectal polyps and carcinoma

Introduction

Most colorectal cancers originate in the glandular mucosa and are therefore histologically adenocarcinomas. Other forms of malignancy in the large bowel such as carcinoid tumour or lymphoma are rare. Squamous carcinomas occur at the anus or in anal canal skin, as do malignant melanomas, but these have an entirely different aetiology and different methods of management; they are discussed in Chapter 30.

Colorectal Polyps

The term polyp is simply a morphological description and describes any localised lesion protruding from the bowel mucosa into the lumen; it does not imply any specific pathology. This conforms to the use of the term elsewhere in the body, e.g. allergic nasal polyps. A simple pathological classification of large bowel polyps is shown in Box 27.1, emphasising the range of polyp types that can occur there.

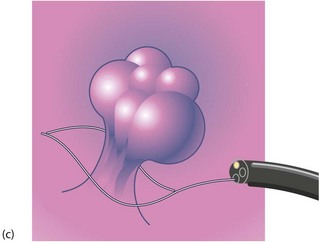

Adenomatous polyps and adenomas: Polyps are common in the large bowel (Fig. 27.1). The most significant are adenomas (i.e. benign neoplasms) and all have potential for malignant change. In general, it takes 5–10 years to progress to invasive cancer. Early removal prevents progression from adenoma to adenocarcinoma. The process by which the epithelial cells acquire increasingly severe genetic mutations is termed the adenoma–carcinoma sequence. Thus, if adenomas are found at endoscopy, all of them should be meticulously removed (Fig. 27.1c) and subjected to histological examination.

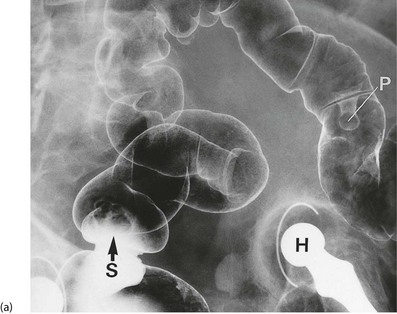

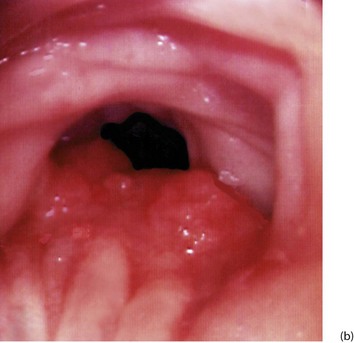

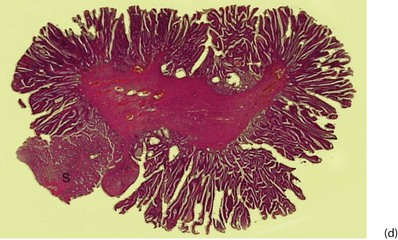

Fig. 27.1 Colorectal polyps

(a) This 65-year-old man was found to have positive faecal occult blood on colorectal cancer screening. This CT colography image shows a solitary polyp in the sigmoid colon, later removed by colonoscopic snaring. It proved to be a benign adenoma. (b) A 2 cm polyp on a long stalk in the sigmoid colon. (c) The snare loop is tightened around the stalk of the polyp before applying diathermy current to remove it and coagulate the blood vessels in the stalk. (d) Adenomatous polyp having mainly villous glandular architecture. The example shown has a well-defined stalk S, although this is more typical of tubular or tubulo-villous polyps, villous adenomas often having a broad base

Classification of colonic adenomas: Three patterns of lesion are recognised histologically: tubular adenomas, villous adenomas and tubulo-villous adenomas.

Tubulo-villous adenomas are intermediate between tubular and villous adenomas and comprise the majority of colonic polyps (Fig. 27.1d). Most are pedunculated, and the stalk is covered with normal colonic epithelium. The stalk probably develops by peristalsis dragging the tumour mass distally and can range from about 0.5 to 10 cm long.

Distribution of colorectal adenomas: Although adenomatous polyps can occur in any part of the large bowel, three-quarters of them arise in rectum and sigmoid colon. This exactly parallels the distribution of carcinomas and provides verification that most cancers develop from polyps.

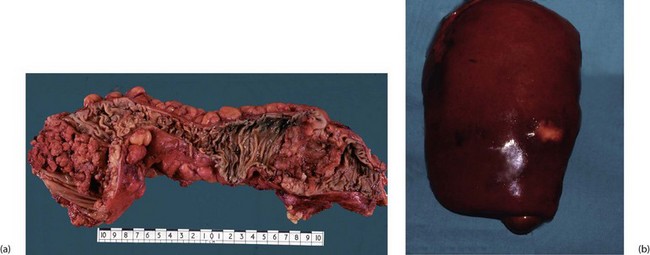

Adenomas often arise singly (particularly villous adenoma) but more than 20% of patients with colonic polyps have multiple polyps, most often tubulo-villous. Patients with proven carcinoma often have coexisting benign adenomas (synchronous), likely to become malignant later if not removed (see Fig. 27.2). This explains why the whole colon should ideally be examined before colectomy, preferably by colonoscopy, and why long-term follow-up after treatment of large bowel cancer should include regular colonoscopy.

Fig. 27.2 Multiple colonic adenomatous polyps

This length of opened descending colon is from a 64-year-old man who presented with an invasive carcinoma of the rectum (not shown here). Several adenomatous polyps of various sizes can be seen in this part of the bowel; the larger polyps have greater malignant potential

Symptoms and signs of colorectal polyps: Many polyps cause no symptoms, and are found incidentally on colonoscopy, barium enema or CT colonography. Symptomatic polyps typically present with rectal bleeding and sometimes iron deficiency anaemia from occult blood loss. Mucus production, especially from villous adenomas, may be so copious as to be the main presenting complaint. Very occasionally, symptomatic hypokalaemia may develop because so much potassium-containing mucus is lost. Distal lesions occasionally produce tenesmus (a painful urge to defaecate) or may prolapse through the anus. Rarely, large polyps can cause obstructive symptoms or intussusception.

Diagnosis and management of colorectal polyps: For symptomatic patients, visualisation of the colon is needed. Most colorectal investigation is somewhat invasive and uncomfortable and the benefits have to be explained to patients, whilst their dignity and privacy is respected as far as possible. In the outpatient clinic, rigid sigmoidoscopy (which actually visualises the rectum) is often performed initially, as nearly half of all polyps lie within reach of the 25 cm instrument. Flexible sigmoidoscopy, usually performed without bowel preparation or after a phosphate enema, reaches past the sigmoid and descending colon to the splenic flexure, covering 75% of the area at risk, but to view the remainder of the bowel requires colonoscopy. Well performed colonoscopy is the ‘gold standard’ investigation: it allows visualisation of the entire large bowel mucosa, and polyps may be removed at the same time. For this reason, it is the first-line investigation in many centres. However, there are disadvantages: it requires a full day’s bowel preparation and the procedure often requires sedation because of the discomfort. Furthermore, colonoscopy carries a 1 : 1000 risk of major haemorrhage or perforation. Sessile, small or flat adenomas in any location can be difficult to recognise even at colonoscopy and these potentially malignant lesions can be missed, especially if bowel preparation has been poor.

Adenocarcinoma of Colon and Rectum

Epidemiology of colorectal carcinoma

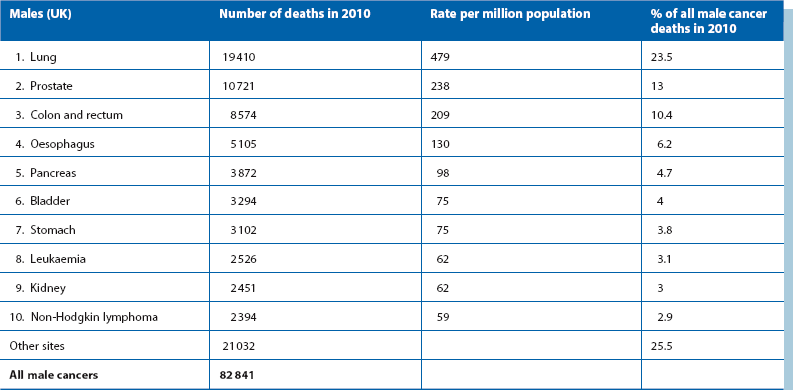

Table 27.1 shows that colorectal cancer is the third most common cause of death from cancer in the developed world; one in 20 people in the UK suffer from it at some point in their lives and almost a third arise in the rectum. The disease is rare before the age of 50 (except in inherited colorectal cancer syndromes, see later) but common after the age of 60. There is little difference in incidence between the sexes.

Table 27.1

Death rates from colorectal cancer compared with other malignancies (UK 2004). Cancers are listed in order of frequency

Ulcerative colitis, a chronic inflammatory condition of the large bowel (Ch. 28), carries an independent risk of bowel neoplasia. After 10 years of active disease, the cancer risk rises by 1% each year.

Inherited conditions causing bowel cancer

Polyposis syndromes: The most important is familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), because it is reasonably common (1 : 30 000 people) and because large bowel cancer is inevitable if untreated. An autosomal dominant defect in the APC gene causes 100 or more adenomatous polyps to develop in the large bowel by the mid teens. Affected patients usually have one parent with the condition. Each affected individual is certain to develop colorectal cancer, at an average age of 40, unless preventative measures are taken. Ideally, prophylactic surgery to remove the area at risk should be performed in early adulthood. One option is subtotal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis which removes nearly all the large bowel but has the retained rectum requires careful very long-term surveillance for malignancy. The alternative is to remove the rectum as well (panproctocolectomy) and perform an ileostomy or an ileal pouch restorative procedure.

Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC): Hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (also known as Lynch syndrome) results from defects in mismatch repair genes which repair damaged DNA. The condition carries a 70% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, but also a substantially increased risk of one or more of other ‘indicator’ cancers such as those of endometrium, ovary, urothelium, small bowel and brain. Families can be difficult to identify because of the diversity of cancers and incomplete genetic penetrance (i.e. not everyone carrying the defect will develop cancer). When HNPCC is suggested by histological characteristics, young age of tumour onset, co-occurrence of tumours or family history, tumour tissue can be screened for markers. If abnormal, formal genetic tests are then undertaken. Those carrying a mutation are best offered colonoscopy every 2 years from the age of 25.

Pathophysiology of colorectal carcinoma

Colorectal carcinomas exhibit a wide range of differentiation which broadly correlates with their clinical behaviour and prognosis (see Fig. 27.5). Most carcinomas are initially exophytic (i.e. protruding into the lumen) and later ulcerate and progressively invade the muscular bowel wall. Eventually, the tumour involves serosa and surrounding structures. Stromal fibrosis may cause luminal narrowing, responsible for the common acute presentation of large bowel obstruction.

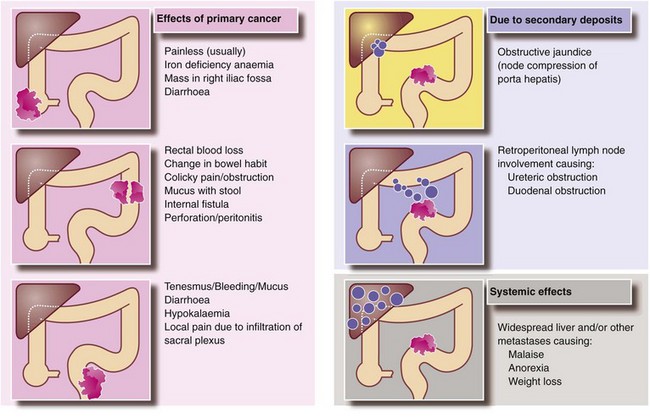

Large bowel carcinomas metastasise via lymphatics and the bloodstream, and by the time of diagnosis as many as 25% of patients already have distant metastases (Fig. 27.4). Lymphatic spread is sequential, first to mesenteric nodes and then onward to para-aortic nodes. Occasionally lymph node involvement is directly responsible for the clinical presentation. For example, para-aortic nodes may present as a palpable mass or cause duodenal obstruction. Other enlarged nodes may compress bile ducts in the porta hepatis causing jaundice.

Presentation of large bowel carcinoma

Blood loss and anaemia: Carcinomas of caecum and ascending colon rarely obstruct unless the ileocaecal valve is involved. This is because the right colon has a larger diameter than the left and the faecal stream is more fluid. However, occult bleeding from the tumour surface commonly causes iron deficiency anaemia, and these patients typically present with anaemia and a palpable mass in the right iliac fossa.

Change of bowel habit and large bowel obstruction: Colorectal cancers usually secrete mucus and bleed into the lumen, which tends to change the bowel habit towards a looser stool. Thus a recent history of loose stool is more likely to predict cancer than increasing constipation, especially since constipation is so common in the elderly population. Faeces in the left colon are more solid and the intraluminal pressure is higher, thus distal cancers here are more likely to obstruct. Colonic cancers tend to progressively encircle the bowel wall, encroaching on the lumen and producing an annular stenosis, taking perhaps a year to involve each quarter of the circumference.

Large bowel obstruction may be partial or complete. Partial obstruction may present as a change in bowel habit, often noticed as constipation with intermittent ‘overflow’ diarrhoea. Complete obstruction precipitates emergency hospital admission (see Ch. 19).

Rectal bleeding: Carcinomas distal to the splenic flexure often cause visible blood to be passed per rectum. The character of the blood and the nature of its mixing with stool depend on how far proximally the lesion is from the anus.

Tenesmus: Carcinomas or polyps in the lower two-thirds of the rectum may be perceived as masses of faeces. This stimulates a persistent defaecation response, causing an unpleasant sensation of incomplete evacuation known as tenesmus.

Perforation: A cancer penetrating the bowel wall may stimulate a vigorous local inflammatory process resulting in a pericolic abscess which contains the perforation, at least for a while. This most often occurs in the rectosigmoid area and usually presents with left iliac fossa pain and tenderness and a swinging fever. The differential diagnosis is acute diverticulitis or a diverticular abscess.

Clinical signs in suspected colorectal carcinoma

These are illustrated in Figure 27.5. General examination may show features suggesting disseminated malignancy, e.g. obvious cachexia or supraclavicular node enlargement. Abdominal examination is usually normal but may reveal a mass in the colon, hepatomegaly due to metastases, or ascitic fluid. Unfortunately, all these signs represent late and often incurable disease.

Investigation of suspected colorectal carcinoma

Where a change in bowel habit (particularly looser stools) or unexplained anaemia is present, any bowel lesion could be left or right sided, and thus the entire colon must be examined by colonoscopy or radiological imaging (Fig. 27.6).

Blood tests: Bowel neoplasms often cause anaemia but liver function tests remain normal until almost all parenchyma is replaced by tumour. Hypokalaemia rarely results from lesions producing excess mucin. Tumour markers are neither sensitive nor specific for a primary diagnosis of colorectal cancer but carcino-embryonic antigen (CEA) is used to monitor cancer recurrence.

Imaging for staging: When colorectal malignancy is diagnosed, surgery is likely to be necessary to relieve symptoms irrespective of distant spread. Staging is performed to guide oncological planning and counselling. Liver and lung metastases are sought, along with other evidence of spread within the abdomen or to bone. CT scanning is the most useful investigation for these but liver ultrasound scanning may be more sensitive for detecting small liver metastases. MRI scanning can add important information about the precise extent of local spread of rectal cancer.

Management of colorectal carcinoma

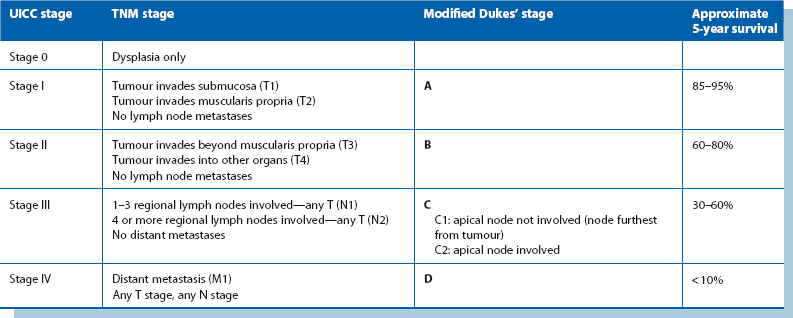

Staging of colorectal carcinoma

Staging of colorectal carcinoma influences the desirability of further treatment by chemotherapy or radiotherapy. It also gives an estimate of the statistical probability of surviving 5 years and the likelihood of cure. Final staging of colorectal cancer depends on information from several sources: the findings at laparotomy, histological examination of the resected specimen and the radiological and other imaging for distant organ spread. The two most widely used staging systems are the tumour/node/metastasis (TNM) and Dukes’ classification, outlined in Table 27.2.

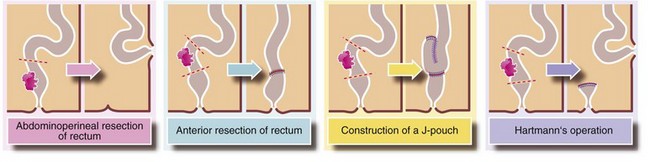

Operations for colorectal cancer

The principles of colorectal tumour resection are as follows:

• Before elective operations, the bowel may be prepared by giving a low residue diet and enemas. Oral purgatives are no longer given because of the potential dehydration

• Perioperative prophylactic antibiotics (e.g. gentamicin and metronidazole) are given

• Operative access is achieved laparoscopically, or by laparotomy, usually via a midline incision

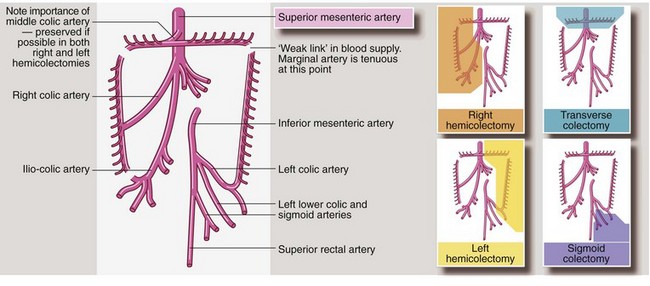

• The affected segment of bowel is removed with a margin of normal bowel, usually 5 cm clear each side of the tumour. There must be a good blood supply to the cut ends of bowel to ensure healing so, in practice, lines of resection are determined by the distribution of mesenteric blood vessels (see Fig. 27.7). For example, ascending colon lesions are treated by removing the whole right colon (right hemicolectomy), as the right colic artery must be ligated in order to remove a section of the right colon

• A wedge-shaped section of colonic mesentery is removed with the bowel. This contains the primary field of lymph node drainage. If there are other obvious lymph node metastases, these are usually included in the resection specimen

• Rectal cancers are a special case and an outline of standard operations is given in Figure 27.8. The preferred operation is a sphincter-saving anterior resection of rectum; provided the lower edge of the tumour is 1–2 cm above the anal sphincters, the sphincter can usually be preserved. This operation involves excising the tumour with an appropriate length of bowel plus an intact envelope of fat around it (the mesorectum containing local lymph nodes). The proximal end of bowel is then anastomosed to the distal stump. Alternatively, a pelvic reservoir is created using a J-pouch technique (Fig. 27.8). This has been shown to reduce the frequency and urgency of defaecation without increasing surgical complications. A temporary defunctioning ileostomy or colostomy is sometimes used to aid healing of a low anastomosis. If the sphincter is involved, the entire rectum and anus has to be removed via an abdomino-perineal excision (APE), with the proximal end of bowel brought out as a colostomy

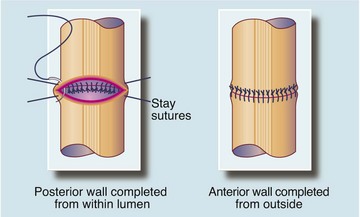

• In most cases, the two cut ends of bowel can be anastomosed without the need for a temporary or permanent colostomy (the indications for stomas and their types and management are described on p. 361 onwards). The method used to rejoin the bowel depends on the site of the anastomosis, the preference of the surgeon and whether there is much disparity in diameter between the ends to be joined. Methods of large bowel anastomosis are shown in Figures 27.9 and 27.10.

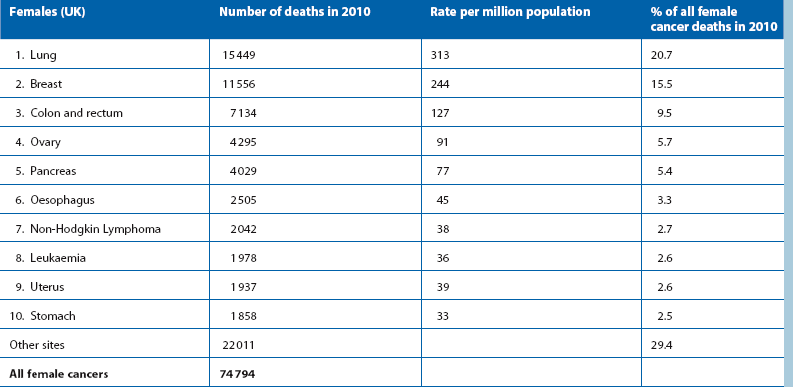

Fig. 27.9 Single-layer method of bowel anastomosis

A single-layer anastomosis using interrupted absorbable sutures is the safest and most commonly used method of anastomosis for nearly all types of bowel. If the bowel cannot be rotated, the posterior layer sutures are placed from inside the bowel and knotted within the lumen. Sutures usually incorporate the muscle wall and submucosa but not the mucosa

Fig. 27.10 Safe and reliable methods of matching the diameter of the bowel ends to effect a safe anastomosis

(a) An end-to-end anastomosis is used when bowel ends are of similar diameter. (b) An end-to-side anastomosis is used where the proximal end is greater in diameter than the distal end, e.g. in small bowel obstruction. (c) A side-to-end anastomosis is used where the distal end is greater in diameter than the proximal end, e.g. in right hemicolectomy

• Postoperatively, an ‘enhanced recovery’ program may be employed to encourage early eating and mobilisation (see Ch. 2, p. 26). These have been shown to lower complication rates and shorten hospital stays.

Management of advanced disease and recurrence

‘Recurrences’ within the colon usually represent new cancers arising metachronously from pre-existing or new adenomas. Careful examination of the entire colon before the first operation is likely to reduce such disease. Local recurrence in rectal cancer is now seen in 5–20% but this was more common before neoadjuvant radiotherapy and before the importance of mesorectal excision in anterior resection was realised (see Fig. 27.3). In abdomino-perineal excision, employing a prone patient position in theatre gives a clearer view of the anatomy and allows wider, more oncological margin clearance to be obtained. Recurrences often cause intractable perineal pain; occasionally a fungating mass grows in the anal region or buttocks. These very distressing complications may be palliated to a degree with radiotherapy.

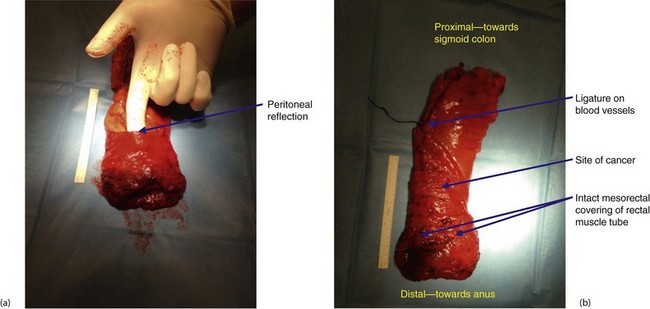

Fig. 27.3 Total mesorectal excision for low rectal carcinoma

Low carcinoma of rectum in a 70-year-old woman who presented with rectal bleeding and a change of bowel habit. A low anterior resection was performed with a covering loop ileostomy. The bowel was rejoined using the circular stapler. Two complete ‘doughnuts’ of tissue indicated successful firing of the stapler (see also Fig. 27.4)

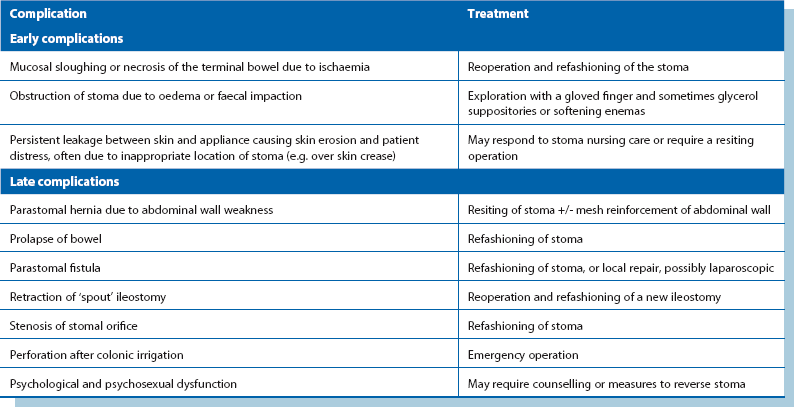

Complications of large bowel surgery

The complications of large bowel surgery are summarised in Box 27.2. Infection arising from faecal contamination is the main early complication of large bowel surgery. Contamination may result from perforation prior to operation, inadvertent faecal spillage during the operation or postoperative anastomotic leakage or breakdown.

Stomas

Indications and general principles

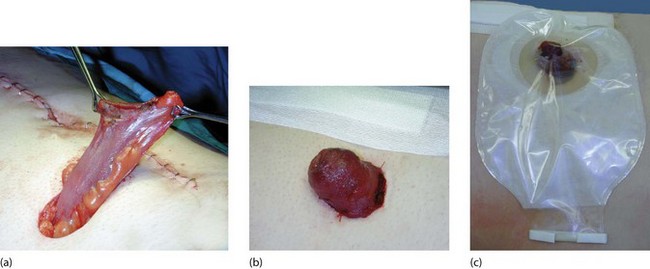

Permanent stomas: These are necessary when there is no distal bowel segment remaining after resection or when for some reason the bowel is not to be rejoined. A colostomy is required after abdomino-perineal excision of a low rectal or anal canal tumour. An ileostomy (see Fig. 27.12) is employed after excision of the whole colon and rectum (pan-proctocolectomy) unless a pouch reconstruction is performed. Sometimes in patients with severe and permanent incontinence, a colostomy may make a better life possible.

Emergency procedures: A temporary stoma may be created (even by an inexperienced surgeon) as an emergency measure to relieve complete distal large bowel obstruction causing proximal bowel dilatation. If the ileocaecal valve remains competent in complete obstruction, the caecum can rupture and cause death by peritonitis. Thus if a patient with large bowel obstruction has a dilated caecum but no small bowel dilatation on plain abdominal X-ray, the ileocaecal valve is likely to be competent. If the patient develops right iliac fossa pain, perforation is imminent. Perforation can be prevented by a timely diverting stoma; the obstructing lesion may be removed at the same operation or later.

Defunctioning stomas: A ‘defunctioning’ stoma (ileostomy or colostomy) may be used to protect a more distal anastomosis at particular risk of leakage or breakdown by preventing intraluminal pressure rises and by diverting the faecal stream. Common examples are a technically difficult low rectal anastomosis (flatus and faeces may leak through the anastomosis), an anastomosis performed after resection of an obstructing lesion (distension may compromise the blood supply), or emergency resection involving unprepared bowel (solid faeces may remain impacted in the lumen). Reversing the temporary stoma to restore bowel continuity is often a relatively simple procedure, usually performed after 3–4 months. Some surgeons like to perform a limited contrast enema to demonstrate anastomotic integrity before closing the stoma.

Types of stoma

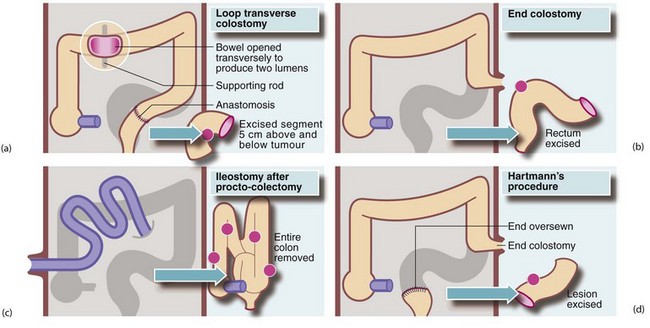

The way in which a stoma is fashioned depends on its purpose. The main types of stoma are described below and illustrated in Figure 27.11. Colonic stomas are designed with the bowel mucosa lying almost flush with the skin. Small bowel stomas are fashioned with a ‘spout’ of bowel protruding about 3 cm, to ensure that the irritant small bowel contents enter the ileostomy appliance directly rather than flowing on to the skin (Fig. 27.12).

Fig. 27.11 Principal types of ileostomy and colostomy

(a) Loop transverse colostomy is usually temporary, and is used to defunction the distal bowel. (b) End colostomy is usually permanent. (c) Ileostomy after procto-colectomy is permanent. Note the protruding ‘spout’ produced by everting the ileum. (d) End colostomy in Hartmann’s procedure sometimes becomes permanent

Loop stoma: This type of stoma is designed so that both proximal and distal segments of bowel drain onto the skin surface (see Fig. 27.11a). This deflects proximal effluent to the skin surface and provides a ‘blow-off’ valve for the distal loop. Loop stomas are used mainly for temporary defunctioning to protect a distal anastomosis. It is straightforward to reanastomose the ends at reversal; the loop is then dropped back into the abdomen. The most common form of loop stoma is the loop ileostomy; occasionally a loop transverse colostomy is used.

Split or ‘spectacle’ stoma: This is the ultimate form of defunctioning stoma but has been largely superseded by the loop stoma. After resection, both proximal and distal bowel ends are brought separately to the skin surface. The proximal end stoma passes stool into a stoma appliance; the distal stoma (or mucous fistula) defunctions the bowel beyond it and produces just a little mucus.

End stoma: This type of stoma is usually permanent. An end colostomy is most commonly used to ‘resite the anus’ on to the abdominal wall after removal of the rectum and anal sphincter (i.e. abdomino-perineal excision—Fig. 27.11b). An ileostomy may be employed after subtotal or pan-proctocolectomy, particularly in fulminant colitis (Fig. 27.11c). Later, some form of reconstruction may be considered, involving an ileal pouch or reservoir in the pelvis composed of loops of ileum sutured side-to-side connected to the anus. The anal sphincter mechanism is preserved so that the patient is usually continent and can control evacuation.

Hartmann’s procedure: end colostomy and rectal stump: Hartmann’s procedure is a relatively safe technique, particularly for less experienced surgeons, and carries less overall risk than primary anastomosis. It is employed after emergency resection of rectosigmoid lesions where primary anastomosis is inadvisable because of obstruction, inflammation or faecal contamination or surgical inexperience. It may be the choice of treatment for frail or debilitated patients. At Hartmann’s operation, the lesion is resected, the proximal bowel is made into an end colostomy (the same as that employed after an abdomino-perineal excision) and the cut end of the distal remnant is closed with sutures or staples (see Fig. 27.11d). Secretions from the residual rectum still pass through the anus. Several months later when local inflammation has resolved, a decision may be made to reconnect the bowel, depending on fitness and the preference of the patient. However, the colostomy is so well tolerated that some patients prefer to keep it permanently rather than undergo another major operation.

Irrigation technique for managing a colostomy: An ileostomy tends to work continuously during the day whereas a colostomy is intermittent. Some patients with a colostomy prefer to dispense with a stoma bag by using a technique of colonic irrigation. Once every few days the patient passes a litre or more of water into the colostomy via a special spout, then the water is allowed to drain out, with the aim of emptying the entire colon. After this, the stoma is covered with a dry dressing as a stoma bag is not needed until the next irrigation.