Colonoscopy

DESCRIPTION OF OPERATION

Appraise

1. Colonoscopy has revolutionized the diagnosis and treatment of colonic disease, allowing accurate mucosal visualization, biopsy and therapeutic polypectomy. Technological advances in instrumentation allow rapid and safe examination of the whole colon, provided the endoscopist has been adequately trained in the technique.

2. Use diagnostic colonoscopy to evaluate an abnormal or equivocal barium enema or CT cologram, particularly where diverticular disease or colonic spasm may often obscure a small mucosal lesion. Colonoscopy should be the first-line investigation for unexplained rectal bleeding or iron deficiency anaemia and is the investigation of choice for all patients with a positive faecal occult blood test. Colonoscopy is the most accurate diagnostic tool for differential diagnosis and assessment of extent in inflammatory bowel disease, but should be avoided in acute disease, where technetium-labelled white cell scanning, if available, is a safer alternative.

3. Therapeutic colonoscopy has changed the management of colorectal polyps, facilitating removal of all pedunculated and most sessile adenomatous lesions, particularly with the advent of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), thus providing an opportunity for colorectal cancer prevention. Diathermy coagulation or laser therapy of vascular abnormalities such as angiodysplasia may pre-empt laparotomy in acute colonic haemorrhage or cure anaemia due to chronic blood loss.

4. Relief of obstruction in colorectal cancer, either as an initial procedure prior to surgical resection or as long-term palliation, may be achieved using either laser vaporization or stent insertion.

5. Perform surveillance colonoscopy with chromoscopy and biopsy of abnormal areas of mucosa in all individuals with a 10 year history of ulcerative or Crohn’s colitis. Further surveillance should be according to current BSG or NICE guidelines, which outline high-risk factors for dysplasia, concomitant family history and primary biliary cirrhosis with recommended intervals between surveillance colonoscopies. Surgery is indicated only in those with definite dysplasia or carcinoma, thus avoiding colectomy in over 80% of cases.

6. Following polypectomy or curative resection for colorectal cancer, carry out regular follow-up colonoscopy, according to the risk factors as outlined in the current BSG guidelines.

7. Commence screening of patients with familial polyposis coli from age 15 years (if gene-positive) and continue approximately 2-yearly until the age of 40 years. Hereditary non-polyposis coli families should undergo 1–2-yearly surveillance, commencing at least 10 years younger than the index case. If facilities exist, then screen subjects with a strong family history of colorectal cancer (i.e. one first-degree relative with onset before 40 years of age, or more than one first-degree relative of any age) in the hope of reducing the incidence of colorectal cancer by removing adenomatous lesions.

8. Emergency colonoscopy is rarely helpful in cases of acute, severe rectal bleeding. Anorectal and upper gastrointestinal causes should be excluded by rigid proctosigmoidoscopy and gastroscopy. Bleeding usually ceases in up to 90% of patients, allowing colonoscopy within 4 to 6 weeks after bowel preparation. In those cases where haemorrhage continues, angiography with embolization of a bleeding point may be helpful. However, if a diagnosis has not been reached and emergency laparotomy becomes necessary, you may perform colonoscopy under general anaesthetic with the peritoneal cavity exposed, following on-table lavage with saline or water introduced via a Foley catheter through a caecostomy.

Prepare

1. Accurate, rapid examination depends upon effective bowel preparation. Advise patients to discontinue any iron preparation or stool-bulking agents 1 week prior to endoscopy and change to a low-residue diet for at least 2 days. Twenty-four hours before examination restrict oral intake to clear fluids such as coffee or tea without milk, concentrated meat extract and glucose drinks. Give a purgative such as sodium picosulphate or ‘low volume’ polyethylene glycol preparation 12–18 hours before colonoscopy and repeat it 4 to 6 hours before examination. Alternatively, give ‘high volume’ balanced electrolyte solution combined with polyethylene glycol, which have been shown to produce rapid preparation without the need for dietary restriction. Administration of metoclopramide 10 mg prior to ingestion of the 3–4 L of solution enhances gastric emptying and reduces nausea and vomiting.

2. Written, informed consent for the procedure should be obtained from all patients prior to bowel preparation and arrival for the procedure. The nature, purpose and risks of the procedure, together with alternatives, should be explained, including the implications of sedation. Give reassurance about the examination to allay fears, allowing minimal levels of sedation to be used.

3. Colonoscopy is usually performed under intravenous sedation with the addition of an analgesic. Do not give excessive sedation or analgesia as this may result in circulatory or respiratory depression. Additionally, it will dull appreciation of severe pain which should occur only when a poor technique is used, causing dangerous overstretching of the bowel. For similar reasons do not perform colonoscopy under general anaesthesia, apart from as an intra-operative procedure in cases of acute colonic haemorrhage. Elderly patients in particular can suffer significant hypotension following pethidine, and this, combined with the synergistic effect of opiates and benzodiazepines, can also cause significant falls in oxygen saturation. In order to avoid these complications, use only small doses of analgesic and hypnotic such as intravenous pethidine 25 mg or fentanyl 50 ug plus midazolam 2–3 mg. Monitor all patients by pulse oximetry, during and after the procedure, and give added inspired oxygen in all cases. Always have available antidotes to benzodiazepines (flumazenil) and opiates (naloxone), together with full cardiorespiratory resuscitation equipment and staff trained to use it in case of emergency. Occasionally an antispasmodic, either intravenous hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan) or intraluminal peppermint oil suspension may be employed.

4. As a rule, commence examination of the patient in the left lateral position or, alternatively, supine. Use a tipping trolley in case of cardiorespiratory problems. Have available at least two trained assistants: one to observe the patient’s vital signs and the other to assist with the accessories for biopsy or snare polypectomy.

5. Check all equipment prior to intubation. The colonoscope must have been adequately cleaned and disinfected. The light source, endoscope angulation controls, air/CO2 insufflation, lens washing and suction facilities must be in full working order. If using a variable stiffness colonoscope ensure that the dial is at ‘0’. Check the diathermy equipment for correct, safe operation. Ensure that all accessories, such as biopsy forceps polypectomy snares and injection needles, are available in the room.

Access

1. Modern colonoscopes are sophisticated precision instruments designed to enhance intubation of the colon in the most efficient manner. As well as a wide-angled lens to allow a greater field of vision and high definition video chip camera, graduated torque characteristics assist variability in the stiffness of the instrument. In addition, some colonoscopes have an ability to vary the stiffness of the insertion shaft.

2. During intubation, the instrument may be pushed forward or pulled back. Change of direction may be achieved by angulation of the distal end, up/down or left/right. Change of direction may also be achieved by up/down deflection, combined with rotation or torque. Keeping the distal section of the instrument as straight as possible and restoring this to a neutral position as soon as possible after angulation around an acute bend helps to prevent loop formation. Avoid maximum up/down and left/right angulation, as this results in a J-shape and rotation of the end of the instrument rather than change of direction. Advancement may also be achieved by the straightening of a loop using torque and withdrawal or by suction, causing a concertina effect of the bowel over the endoscope.

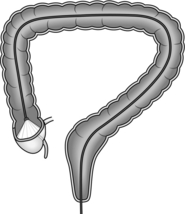

3. Colonoscopy is made easier if the anatomy of the colon is properly understood. The rectum is fixed in a retroperitoneal position and consists of alternating mucosal folds forming the valves of Houston. The sigmoid colon is freely mobile on its mesentery and of variable length and configuration. The descending colon and splenic flexure are relatively fixed by their peritoneal attachments. At the splenic flexure, the direction of the colon is forwards and downwards to the transverse colon which, like the sigmoid, is of variable length and freely mobile on the transverse mesocolon. The bowel becomes fixed again at the hepatic flexure and the direction passes forwards and downwards into the ascending colon and caecum, which are usually fixed by peritoneal attachments, though less consistently than the descending colon. It is the mobile and variable-length sigmoid and transverse colon that cause the most difficulty through looping of the instrument.

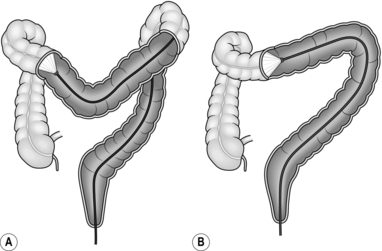

4. The aim of colonoscopy is to achieve intubation from the anus to caecum with the minimum possible length of instrument. Characteristically, the colonoscope, when straight and without loop formation, should be in a roughly U-shaped configuration with 70–80 cm of instrument inserted to the caecal pole (Fig. 12.1). Significantly greater insertion length indicates the presence of a loop.

Fig. 12.1 Colonoscope inserted to the caecal pole.

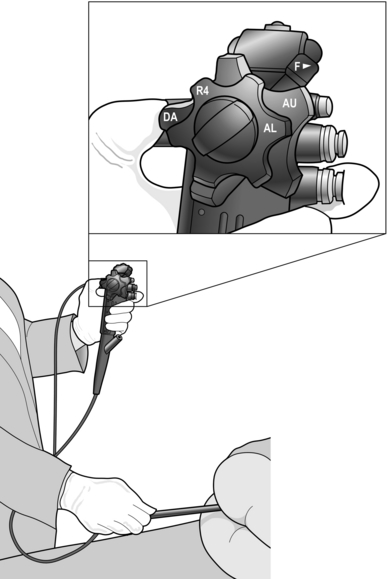

5. Liberally lubricate the anus and perianal area with lubricating gel. Carry out a thorough digital examination then introduce the instrument along the forefinger of the right hand. Repeated lubrication is required to prevent friction at the anus, one of the commonest causes of failure to advance the endoscope. Control of the instrument is best achieved by rotation of the up/down and left/right angulation control wheels, using your left thumb. Place your index finger to allow it to operate the air/water and suction valves. Manipulation of the colonoscope shaft is performed with the right hand (Fig. 12.2).

6. On entering the rectum, aspirate excess fluid and adjust the tip of the instrument, using torque, until it is in the centre of the lumen. During intubation, insufflate only the minimum amount of air to allow adequate visualization of the lumen. Excessive air leads to distal distension and accentuation of angles in the bowel. At the rectosigmoid junction the lumen passes upwards and to the right. Intubation at this point can be achieved by upward deflection of the tip and clockwise rotation of the shaft. In patients with a relatively short sigmoid colon, continuation of the clockwise rotation with advancement often leads to passage as far as the descending sigmoid junction. Intubation of the rectosigmoid can often be the most uncomfortable part of the procedure for the patient; if excess angulation is required to view the lumen then change the patient position to supine or right lateral to decrease the rectosigmoid angle and allow intubation with minimal tip angulation. In many patients, particularly those with diverticular disease or those who have undergone pelvic surgery, the configuration is variable and there may be a number of acute angles. In these cases, achieve advancement by a combination of, position change, torque and adjustments to the left/right wheel. Aim to take the shortest possible route through the bowel, keeping the instrument tip in the centre of the lumen and keeping to the inside of each bend.

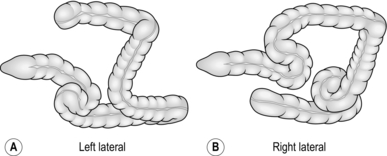

7. Looping of the colonoscope may occur in the sigmoid colon, indicated by a lack of one-to-one advancement of the instrument tip compared with the shaft, which may also cause the patient some discomfort. Straighten the loop by applying rotational torque to the shaft, in the direction that produces the least resistance, while at the same time withdrawing the instrument. Once one-to-one withdrawal has been achieved, re-advance the instrument while maintaining the same torque, preventing reformation of the loop. In the sigmoid colon, the torque usually needs to be applied in a clockwise direction. The effect of this is to fold the sigmoid loop over and achieve a relatively straight sigmoid colon (Fig. 12.5).

8. Although there are variations between patients, the transverse colon is usually found by rotating the tip to the left and downwards. In many patients, the splenic flexure is acutely angled, resulting in sigmoid looping as advancement is attempted. Changing the position of the patient to the right lateral allows the transverse colon to drop away from the flexure thus decreasing the angle. Once the characteristic triangular lumen of the transverse colon is recognized, straighten the tip and advance the instrument with a combination of intermittent suction and insertion. This has the effect of making the bowel concertina over the colonoscope and shortening the effective length. The transverse colon usually has at least one acute angle at its centre point, but may have more, particularly if postoperative adhesions are present. On reaching such an angle, angle the tip around the bend and, while maintaining a luminal view, apply torque and withdrawal as for the sigmoid loop, again in the direction of least resistance. In order to prevent possible trauma to the colon, always maintain a luminal view and do not hook the end of the instrument into the bowel wall. The effect of this manoeuvre is to straighten the transverse colon (Fig. 12.6).

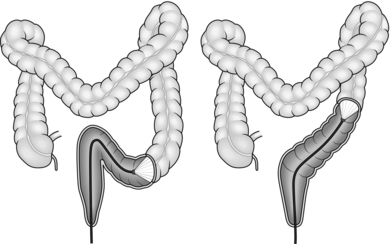

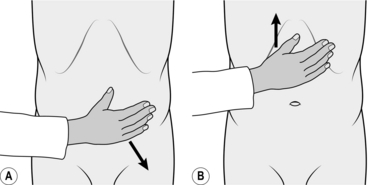

As soon as one-to-one advancement is achieved, straighten the tip and advance the instrument, again using intermittent suction. If this manoeuvre does not result in easy one-to-one advancement, position change to supine or right lateral can be helpful. The tip of the instrument should then pass rapidly to the hepatic flexure, which may be recognizable by a bluish hue of the right lobe of the liver visible through the colonic wall. However, this is an unreliable landmark as the left lobe of the liver can give the same appearance in the mid-transverse colon. Occasionally, during the process of straightening the transverse colon, the sigmoid loop may re-form. It is useful at this stage, having re-straightened the sigmoid loop, either to employ an assistant to hold the sigmoid or transverse loop in its straightened configuration or increase the stiffness of the insertion shaft if using a variable stiffness colonoscope. In the case of the sigmoid colon, abdominal compression is performed using the flat of the hand to exert pressure downwards and towards the left iliac crest (Fig. 12.7A). For recurrent transverse looping, the colon is splinted by the assistant’s hand pushing upwards from just above the umbilicus (Fig. 12.7B).

9. At the hepatic flexure, entrance to the caecum is usually found by angulation down and rotation to the left. The caecum often has a pool of fluid at its pole and the ileocaecal valve is visible as a shelf-like protrusion, with a lip-like centre. Advancement to the caecal pole can usually be achieved by a combination of suction and gentle advancement. If a transverse loop has re-formed, then straighten the loop and re-advance, using assistant compression, or, providing the patient does not experience excessive discomfort and there is no resistance to intubation, a transverse loop can be deliberately formed and then, following angulation of the tip into the upper ascending colon, straightening of the scope by withdrawal combined with torque achieves advancement to the caecal pole. An alternative solution is to ask the patient to move back into the left lateral position, which will often result in a less-acute angle to be negotiated.

10. The only reliable landmarks in colonoscopy are seen on entering the caecum. Typically, there is a triradiate fold at the caecal pole, representing the convergence of the taeniae coli, at the centre of which may be seen the base of the appendix. Palpation of the abdomen, laterally in the right iliac fossa, produces indentation of the caecal wall, and the light of the colonoscope may also be visible through the abdominal wall. However, all of these appearances may be mimicked by a deep transverse loop, and the ileocaecal valve or terminal ileum is the only reliable sign that the caecum has been reached. The appearance of the ileocaecal valve may vary, but its usual appearance is of a lip-like structure. Intubation of the valve shows an obvious change in the mucosal pattern, from the shiny mucosa of the colon with visible blood vessels to the rather granular appearance of the distal ileum, often with visible lymphoid patches, and a characteristic advancing peristaltic movement.

Assess

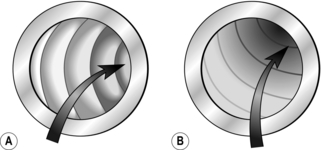

1. Whilst much of the examination is carried out during intubation, perform a thorough inspection of the colon during withdrawal of the instrument. By using a combination of up/down deflection and rotation to create a figure-of-eight motion, it is possible to examine the colonic mucosa completely, particularly behind the circular muscle folds. A proper examination during withdrawal should take at least 6 minutes to avoid missing any mucosal lesions.

2. Keep your right hand on the shaft of the colonoscope, approximately 15–20 cm from the anus, since straightening of a loop often leads to rapid distal progression of the instrument. This requires rapid re-insertion to avoid overlooking any area of the mucosa. During extubation, insufflate more air/CO2 in order to straighten the haustral folds. As each segment of colon is examined, suck out the air in order to prevent undue discomfort and possible vasovagal attacks due to over-distension. At this stage, if spasm becomes a problem then inject intravenous hyoscine butylbromide or instil peppermint oil suspension into the colon via the biopsy channel to relieve the spasm and allow adequate visualization.

3. The normal appearance of the colon is a shiny mucosal surface, with a clearly visible vascular pattern. Loss of vascular pattern is the earliest sign of inflammatory bowel disease, followed by granular, friable mucosa and frank ulceration as the disease intensifies. Chronic disease may be manifest by pseudopolyps and stricture formation. The presence of ‘skip lesions’ separated by areas of normal mucosa, aphthous ulceration and deep fissuring (‘cobblestone mucosa’) is characteristic of Crohn’s disease. The commonest types of polyp to be encountered are either adenomatous or hyperplastic. High definition endoscopes combined with either chromoscopy or narrow band imaging will allow classification of most polyps; however, in cases of doubt, or operator inexperience, remove these for histological assessment. Biopsy polypoid or plaque-like areas in cases of established ulcerative colitis to exclude dysplastic or neoplastic change.

Action

1. During colonoscopy, take biopsies or perform polypectomy. Introduce endoscopic accessories only when there is a clear luminal view, to avoid the risk of perforation. The most convenient biopsy forceps are those of the spiked variety, which remove adequate-sized samples of tissue and will not slide off the mucosa when attempting biopsy at a tangent. Hot biopsy, traditionally used for small sessile polyps, is potentially dangerous, carrying a high risk of perforation or delayed bleeding, and often produces inadequate material for accurate histology, whilst showing no evidence of decreasing polyp recurrence. Mount biopsy specimens carefully according to the preference of the histopathologist. Clearly label containers. Preferably, use a diagram of the colon on the histology request form, with specimens appropriately labelled to allow accurate identification of biopsy sites. In the case of strictures, use brush cytology when adequate biopsies cannot be obtained.

2. Perform coagulation of areas of angiodysplasia only if there are signs of ulceration or recent bleeding. Using coagulation forceps pick up the edge of the lesion, tenting it away from the colonic wall and drawing it over the centre of the lesion before applying the current. Alternatively, use argon plasma coagulation or laser vaporization.

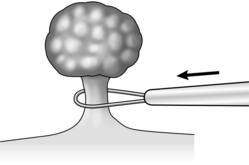

3. Prior to snare polypectomy, make sure that you are familiar with the diathermy equipment and manufacturer’s guidance. Diathermy power is delivered in different modes: coagulation, cut, a blend of coagulation and cut, or sequential cut and coagulation. The way in which the power is delivered affects both the mode of application of current and tightening of the snare. Always mark the snare in the fully closed position, allowing assessment of the amount of tissue enclosed in the snare: this avoids the risk of over-enthusiastic tightening or ‘cheese-wiring’ of the polyp with the risk of subsequent haemorrhage. Make sure that injection needles with adrenalin solution, together with endoscopic clips and endoloops are readily available in order to deal with any bleeding. Ensure that the colonoscope is as straight as possible and the instrument tip is rotated to position the biopsy channel in line with the polyp. After introducing the snare, open it and manoeuvre it over the polyp. Adjust its position around the polyp stalk. Gradually close the snare while advancing the covering tube up to the stalk (Fig. 12.8). Do not apply diathermy current until the snare is closed around the polyp stalk, or the colonic wall beyond the polyp could be burned. Apply coagulation diathermy in the manner recommended by the diathermy manufacturer whilst slowly closing the snare.

Fig. 12.8 When snaring a polyp, gradually close the snare while advancing the covering tube up to the stalk.

4. Retrieve polyps for histological examination by either lassoing them with the snare or capturing them in a polyp retrieval basket. Alternatively, they may be sucked on to the end of the endoscope and withdrawn en masse by extubation. Small polyps (≤ 5 mm) may be sucked through the biopsy channel and retrieved into a polyp trap inserted into the suction line. Snares may be used not only for pedunculated polyps but also for sessile lesions. Submucosal injection of saline to raise the polyp from the muscularis mucosae not only facilitates placement of the snare, but reduces the risk of perforation and makes dealing with any bleeding vessels much easier. This technique allows snare polypectomy of lesions up to 2 cm in size. Larger lesions should be removed by endoscopic mucosal resection or submucosal dissection, usually in specialist centres that have expertise in these techniques. Piecemeal polypectomy should be avoided as it makes histopathological assessment of completeness of excision and staging impossible. If the polyp does not completely raise after the injection and there is central tethering, malignancy should be suspected and a biopsy taken. When large polyps are removed, the mucosa adjacent to the polypectomy site (distal to the site in the right colon, proximal in the left colon) should be marked by raising a bleb of submucosal saline injection, followed by injection of Indian ink into the bleb in at least three quadrants circumferentially. This allows easy identification of the site at follow-up colonoscopy, or marking of the site for subsequent laparoscopic or open resection if the polyp exhibits malignant change.

Aftercare

1. Have the patient observed by a trained nurse during recovery from sedation and ensure continuation of pulse oximetry monitoring until the patient is fully awake. Excessive insufflation of air during intubation may lead to nausea and vomiting, which is potentially dangerous in the sedated patient. Once fully awake, allow patients to go home provided they are accompanied by a responsible adult. Advise patients against driving or operating machinery for a period of 24 hours after sedation.

2. Ensure that the colonoscope is cleaned and disinfected following the procedure in accordance with the appropriate guidelines for decontamination of flexible endoscopes, and all equipment is checked for correct operation.

Complications

1. Apart from the effects of sedation, complications of diagnostic colonoscopy include perforation and haemorrhage, occurring in 0.1% to 0.3% of cases, with approximately 10 times this rate following polypectomy. However, these rates are quoted from a number of colonoscopic series, some very early in the evolution of colonoscopy, when instrument design was less advanced and endoscopists were learning the techniques. Nevertheless, complications still occur, particularly when the colonoscopist is inexperienced, so remember that patient pain is an important warning sign of dangerous overstretching of the bowel. This must not be masked by heavy sedation or analgesia. Similarly, never perform routine colonoscopy under general anaesthesia.

2. Many of the reported cases of postpolypectomy perforation and haemorrhage occur late (up to 72 hours post-procedure), usually because excessive diathermy current has been used, causing transmural burns or secondary haemorrhage. Advise patients to be seen by an experienced clinician if pain or bleeding occurs at any time following the procedure.

American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Standards of Practice Committee. Complications of colonoscopy. Oak Brook, IL: ASGE. Available at http://www.asge.org/WorkArea/downloadasset.aspx?id=3342&LangType=1033; accessed 2003.

British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). London: BSG. Available at http://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical-guidelines/endoscopy/guidelines-for-colorectal-cancer-screening-and-surveillance-in-moderate-and-high-risk-groups-update-from-2002.html; accessed 2010.

British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines on decontamination of equipment for gastrointestinal endoscopy. London: BSG. Available at www.bsg.org.uk/pdf_word_docs/decontamination_2008.pdf; accessed 2008.

British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidance for obtaining a valid consent for elective endoscopic procedures. London: BSG. Available at http://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical-guidelines/endoscopy/guidance-for-obtaining-a-valid-consent-for-elective-endoscopic-procedures.html; accessed 2008.

British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines on safety and sedation during endoscopic procedures. London: BSG. Available at http://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical-guidelines/endoscopy/guidelines-on-safety-and-sedation-during-endoscopic-procedures.html; accessed 2003 and 2006.

Cotton, P.B., Williams, C.B., Hawes, R.H., Saunders, B.P. Practical Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: The Fundamentals, 6th ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Colonoscopic surveillance for prevention of colorectal cancer in people with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease or adenomas. London: NICE. Available at http://guidance.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13415/53592/53592.pdf; accessed March 2011.

Riley SA. Colonoscopic polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection: A practical guide. London: BSG. Available at http://www.bsg.org.uk/pdf_word_docs/polypectomy_08.pdf; accessed 2008.

Wada, Y., Kashida, H., Kudo, S.E., et al. Diagnostic accuracy of pit pattern and vascular pattern analyses in colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc. 2010; 22(3):192–199.

Waye, J.D., Rex, D.K., Williams, C.B. Colonoscopy: Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.