CHAPTER 54 COLON AND RECTAL INJURIES

Surgical management of colon and rectal injuries has evolved dramatically since World War II. Accepted treatment at that time generally consisted of resection and end colostomy based on experience with battlefield casualties. Although a difference between civilian and military injuries was recognized, the treatment by civilian trauma surgeons paralleled that of their military counterparts. In the ensuing decades following the Korean and Vietnam wars, primary repair began to replace the “colostomy only” approach in the nonmilitary setting. Numerous prospective randomized trials in civilian centers have since established primary repair as the preferred treatment for most colon and rectal injuries.

ANATOMIC LOCATION AND INJURY GRADING

The Organ Injury Scaling Committee of the American Association of the Surgery of Trauma has developed colon and rectal injury scales that facilitate comparison of injuries between patients and facilities and helps identify patients at high risk for postoperative complications (Tables 1 and 2).

| Grade | Injury Description | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hematoma | Contusion or hematoma without devascularization |

| Laceration | Partial thickness, no perforation | |

| II | Laceration | Laceration <50% of circumference |

| III | Laceration | Laceration >50% of circumference |

| IV | Laceration | Transection of colon |

| V | Laceration | Transection with segmental tissue loss |

Note: Advance one grade for multiple injuries up to grade III.

Modified from Organ Injury Scaling Committee of the American Association of the Surgery of Trauma.

Table 2 AAST Rectal Injury Grading

| Grade | Injury Description | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Hematoma | Contusion or hematoma without devascularization |

| Laceration | Partial thickness, no perforation | |

| II | Laceration | Laceration <50% of circumference |

| III | Laceration | Laceration >50% of circumference |

| IV | Laceration | Full-thickness laceration with extension into perineum |

| V | Vascular | Devascularized segment |

Note: Advance one grade for multiple injuries to the same organ.

Modified from Organ Injury Scaling Committee of the American Association of the Surgery of Trauma.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The current management strategies for colon and rectal injuries have been scientifically established in recent decades in civilian trauma centers where operations are generally performed shortly after injury in patients who have been resuscitated and treated with antibiotics. There are two generally accepted surgical options for contemporary management of colon injuries: primary repair or colostomy. Primary repair, whether direct closure of a defect or segmental resection and primary anastomosis, implies that the initial surgical intervention is definitive and no further treatment is necessary. Colostomy options include proximal end colostomy or ileostomy with distal mucous fistula or distal closure (Hartman’s procedure), loop colostomy of the injured segment, and diverting colostomy proximal to suture repair.

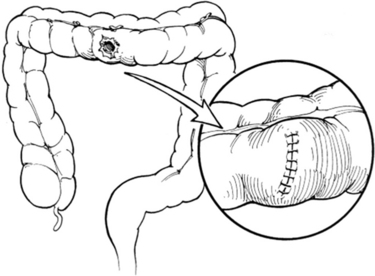

Most authorities would agree that modern treatment of colon injuries is either by primary repair or colostomy. Although primary repair of all colon injuries in the nonmilitary setting is a desirable goal, it is not always possible. The key to successful management is patient selection based on the location and degree of injury and the physiologic state of the patient at the time of repair. For simple nondestructive injuries that do not require segmental resection (AAST CIS I–III), the treatment of choice is primary suture repair. Debridement is kept to a minimum except to remove grossly contaminated or ischemic tissue. We employ a single transverse closure using absorbable monofilament suture beginning a few millimeters from each end of the colostomy. Sutures are placed to gently oppose the seromuscular layer in a continuous Lembert fashion (Figure 1).

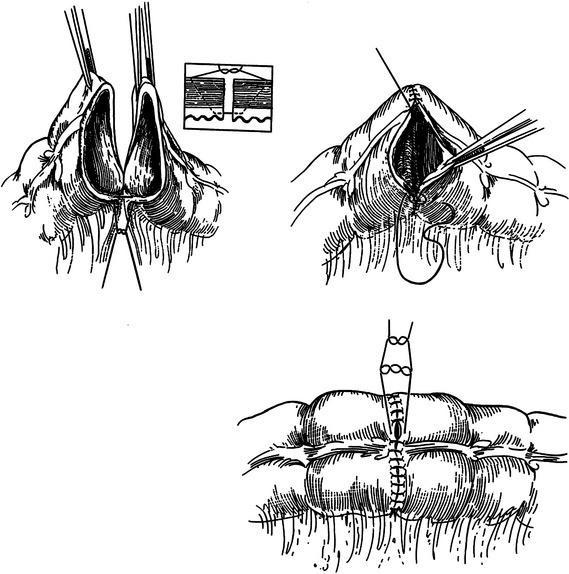

Although several methods have been described for creation of ileocolostomy and colocolostomy, we prefer the end-to-end, single-layer technique using absorbable monofilament suture (Figure 2). The suture line is started at the mesenteric border using a double-armed 3-0 polydiaxone suture. Sutures are then placed 3–4 mm from the cut edge of the bowel to include all layers but the mucosa. Each arm is advanced around the bowel and tied at the antimesenteric border resembling a vascular anastomosis. Disparity in bowel caliber can be solved by extension of the enterotomy on the smaller end along the antimesenteric border. The mesenteric defect is then closed with a continuous absorbable suture.

Destructive colon injuries distal to the middle colic artery in patients with multiple risk factors for suture line failure should be treated with colostomy. The damaged section of the colon is resected using a GIA stapler and the proximal end of the colon used for the colostomy. The key technical aspects of colostomy are to ensure that the clamped end of the colon reaches the skin level with no tension, that the end of the colon has an adequate blood supply, and that the colostomy is immediately matured with sutures between the mucosa and the skin without tension. The distal end of the defunctionalized colon is left closed with staples. Treatment of the distal colon segment with mucous fistula is avoided because it is time consuming, is of no additional benefit, adds the potential complications of a second stoma, and adds difficulty to subsequent colostomy closure.

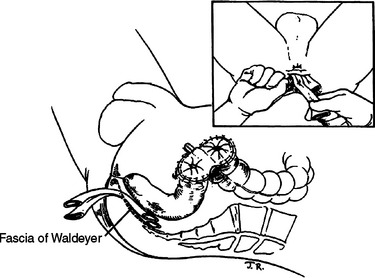

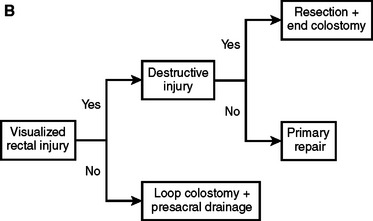

Rectal injuries identified either preoperatively or during abdominal exploration should be repaired. As noted previously, the only indication of a rectal injury may be the presence of intraluminal blood or a submucosal hematoma observed during rigid proctoscopy. Wounds to the extraperitoneal rectum with little or no loss of the rectal wall can be treated with colostomy and presacral drainage alone. Extensive dissection to definitively visualize distal rectal injuries should be avoided because of the potential for vascular, urologic, neurologic, or iatrogenic rectal injury. In such cases, the patient is treated as if a rectal injury is present with presacral drainage and proximal diversion (Figure 3). A curved incision is made posterior to the anus and the presacral space developed bluntly to the level of the sacrum. Ideally, Penrose drains are placed in proximity but not in contact with the injury. The drains are secured to the skin with silk sutures for better patient comfort and usually removed between 4 and 7 days postinjury. Although several methods for proximal diversion are described, it is essential that the chosen technique must completely divert the fecal stream from the rectal injury. We employ a loop colostomy located in the patient’s left lower quadrant using the sigmoid colon. The critical technical elements to ensure complete diversion are creating a longitudinal colotomy, maintaining the common wall or spur between the afferent and efferent limbs above the level of the skin, and maturing the stoma to the skin immediately. A loop colostomy created in this manner completely diverts the fecal stream.

Nondestructive rectal injuries that do not require resection based on intraoperative evaluation (AAST RIS I–III) are repaired primarily. These injuries are generally lacerations with minimal surrounding tissue destruction that are easily exposed and sutured. The location may be intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal and exposed after mobilization of the proximal rectum. The technique used is the same as that for primary repair of colon injuries using a running single layer of 3-0 polydiaxone suture. Placement of drains in the pelvis is not necessary and may increase the risk of fistula.

CONCLUSIONS AND ALGORITHM

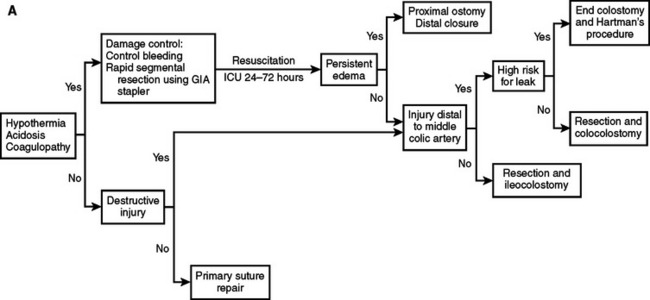

With these considerations, we have adopted an institutional approach to colon and rectal injuries outlined in Figure 4. The critical decision-making points for colon injuries are the metabolic status of the patient, the need for segmental resection, the location of the injury, and the condition of the bowel at the time of repair. Adherence to this approach enables primary repair in 70%–90% of patients. The first consideration in rectal injuries is whether the injury is identified and repaired. Patients with suspected injuries that are not directly identified or not repaired because of anatomic location are treated with proximal diversion and presacral drainage. Rectal injuries requiring segmental resection are best treated with colostomy rather than primary anastomosis during the initial operation.

Burch JM, Brock JC, Gevirtzman L, et al. The injured colon. Ann Surg. 1986;203(6):701-711.

Burch JM, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL. Colostomy and drainage for civilian rectal injuries: is that all? Ann Surg. 1989;209(5):600-610. discussion 610–611

Burch JM, Franciose RJ, Moore EE, et al. Single-layer continuous versus two-layer interrupted intestinal anastomosis: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2000;231(6):832-837.

Burch JM, Ortiz VB, Richardson RJ, et al. Abbreviated laparotomy and planned reoperation for critically injured patients. Ann Surg. 1992;215(5):476-483. discussion 483–484

Demetriades D, Murray JA, Chan L, et al. Penetrating colon injuries requiring resection: diversion or primary anastomosis? An AAST prospective multicenter study. J Trauma. 2001;50(5):765-775.

George SMJr, Fabian TC, Voeller GR, et al. Primary repair of colon wounds. A prospective trial in nonselected patients. Ann Surg. 1989;209(6):728-733. 733–734

Gonzalez RP, Merlotti GJ, Holevar MR. Colostomy in penetrating colon injury: is it necessary? J Trauma. 1996;41(2):271-275.

Ivatury RR, Licata J, Gunduz Y, et al. Management options in penetrating rectal injuries. Am Surg. 1991;57(1):50-55.

Maxwell RA, Fabian TC. Current management of colon trauma. World J Surg. 2003;27(6):632-639. (Epub 2003 May 2.)

Miller PR, Fabian TC, Croce MA, et al. Improving outcomes following penetrating colon wounds: application of a clinical pathway. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):775-781.

Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malangoni MA, et al. Organ injury scaling. II: pancreas, duodenum, small bowel, colon, and rectum. J Trauma. 1990;30(11):1427-1429.

Nelson R, Singer M. Primary repair for penetrating colon injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;3:CD002247.

Renz BM, Feliciano DV, Sherman R. Same admission colostomy closure (SACC). A new approach to rectal wounds: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 1993;218(3):279-292. discussion 292–293

Rombeau JL, Wilk PJ, Turnbull RBJr, Fazio VW. Total fecal diversion by the temporary skin-level loop transverse colostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1978;21(4):223-226.

Vitale GC, Richardson JD, Flint LM. Successful management of injuries to the extraperitoneal rectum. Am Surg. 1983;49(3):159-162.

Williams MD, Watts D, Fakhry S. Colon injury after blunt abdominal trauma: results of the EAST Multi-Institutional Hollow Viscus Injury Study. J Trauma. 2003;55(5):906-912.