Colon

Preoperative assessment of the large bowel

Laparoscopic right hemicolectomy

Laparoscopic left hemicolectomy

Anterior resection of the rectum

Laparoscopic anterior resection

Abdominoperineal excision of the rectum

Colectomy for inflammatory bowel disease

Elective colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis

PREOPERATIVE ASSESSMENT OF THE LARGE BOWEL

1. Obtain a full history and examine the abdomen, anus and rectum in every patient before undertaking surgery. Carry out further investigations as necessary:

Rigid sigmoidoscopy. Although increasingly superseded by flexible sigmoidoscopy, this remains a useful investigation in outpatients presenting with bowel symptoms as it allows for prompt identification and biopsy of rectal pathology such as carcinoma, proctitis or solitary rectal ulcer.

Rigid sigmoidoscopy. Although increasingly superseded by flexible sigmoidoscopy, this remains a useful investigation in outpatients presenting with bowel symptoms as it allows for prompt identification and biopsy of rectal pathology such as carcinoma, proctitis or solitary rectal ulcer.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy. This can be undertaken as an outpatient procedure without sedation after bowel preparation with phosphate enemas. 60-cm scopes are available and easier to control but if you are experienced choose either a 90-cm scope or full-length colonoscope as they allow examination of the entire left colon in all patients.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy. This can be undertaken as an outpatient procedure without sedation after bowel preparation with phosphate enemas. 60-cm scopes are available and easier to control but if you are experienced choose either a 90-cm scope or full-length colonoscope as they allow examination of the entire left colon in all patients.

Colonoscopy (see Chapter 12). This is the investigation of choice for the large bowel, although not without risks, especially in the elderly or during therapeutic procedures. Biopsies can be obtained from tumours and inflammatory bowel disease and pedunculated polyps can be removed by colonoscopic snaring. More advanced procedures, such as endoscopic submucosal resection and stenting, are available in many centres. The risk of perforation is approximately 1:800; removal of large polyps also carries a significant risk of bleeding although this can usually be controlled endoscopically.

Colonoscopy (see Chapter 12). This is the investigation of choice for the large bowel, although not without risks, especially in the elderly or during therapeutic procedures. Biopsies can be obtained from tumours and inflammatory bowel disease and pedunculated polyps can be removed by colonoscopic snaring. More advanced procedures, such as endoscopic submucosal resection and stenting, are available in many centres. The risk of perforation is approximately 1:800; removal of large polyps also carries a significant risk of bleeding although this can usually be controlled endoscopically.

CT colography (virtual colonoscopy). With the advent of spiral computed tomography (CT), the technique of CT colography or virtual colonoscopy has achieved diagnostic sensitivity equivalent to optical colonoscopy. Advantages over colonoscopy are a reduced risk of perforation, the ability to image the bowel proximal to strictures and the detection of other intra-abdominal and pelvic pathology. A significant abnormality on virtual colonoscopy usually demands confirmation by optical colonoscopy and biopsy.

CT colography (virtual colonoscopy). With the advent of spiral computed tomography (CT), the technique of CT colography or virtual colonoscopy has achieved diagnostic sensitivity equivalent to optical colonoscopy. Advantages over colonoscopy are a reduced risk of perforation, the ability to image the bowel proximal to strictures and the detection of other intra-abdominal and pelvic pathology. A significant abnormality on virtual colonoscopy usually demands confirmation by optical colonoscopy and biopsy.

Barium enema. Double-contrast barium enema is less sensitive than colonoscopy but is still widely used in hospitals where access to endoscopy and CT is limited.

Barium enema. Double-contrast barium enema is less sensitive than colonoscopy but is still widely used in hospitals where access to endoscopy and CT is limited.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan. The investigation of choice in the acute abdomen, bowel obstruction and acute diverticulitis. A CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis is now routinely used in staging colorectal cancer.

Contrast-enhanced CT scan. The investigation of choice in the acute abdomen, bowel obstruction and acute diverticulitis. A CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis is now routinely used in staging colorectal cancer.

MRI. The ‘Gold Standard’ investigation in preoperative staging for rectal cancer and increasingly employed in imaging inflammatory bowel disease due to the absence of radiation risks.

MRI. The ‘Gold Standard’ investigation in preoperative staging for rectal cancer and increasingly employed in imaging inflammatory bowel disease due to the absence of radiation risks.

Other examinations. Stool microscopy and culture are essential to differentiate bacterial and parasitic infection from inflammatory bowel disease. Order an erect chest/abdominal X-ray in suspected bowel obstruction or perforation. Serial abdominal films are also important in acute fulminant colitis to detect the onset of toxic megacolon. Ultrasound scans are of value in diagnosing abdominal masses, intra-abdominal collections and possible metastases. Ultrasonography is more readily available than CT scanning, but diagnostic accuracy is operator-dependent. Employ angiography in the management of severe gastrointestinal haemorrhage: this can be combined with therapeutic embolization of the bleeding vessel.

Other examinations. Stool microscopy and culture are essential to differentiate bacterial and parasitic infection from inflammatory bowel disease. Order an erect chest/abdominal X-ray in suspected bowel obstruction or perforation. Serial abdominal films are also important in acute fulminant colitis to detect the onset of toxic megacolon. Ultrasound scans are of value in diagnosing abdominal masses, intra-abdominal collections and possible metastases. Ultrasonography is more readily available than CT scanning, but diagnostic accuracy is operator-dependent. Employ angiography in the management of severe gastrointestinal haemorrhage: this can be combined with therapeutic embolization of the bleeding vessel.

ELECTIVE OPERATIONS

CARCINOMA

Assess

1. Perform a full laparotomy or laparoscopy, particularly if preoperative CT scanning has not been performed.

2. Examine the whole of the colon from the appendix to the rectum. Synchronous carcinomas occur in 4% of patients; adenomatous polyps cannot usually be palpated.

3. Avoid handling the carcinoma. Cover it with a swab soaked in 10% aqueous povidone-iodine solution.

4. Feel for enlarged lymph nodes in the mesentery and para-aortic region. Look and feel for liver and peritoneal metastases.

5. Assess the resectability and curability of the tumour.

6. If you discover unexpected liver metastases in the presence of a potentially resectable tumour do not biopsy them, as this may result in trans-peritoneal spread of tumour. In selected patients with solitary or localized liver metastases it may be appropriate to perform a synchronous metastasectomy if you have the relevant expertise. For multiple liver metastases the increased morbidity outweighs any benefit. Proceed with the planned bowel resection and refer the patient to a specialist liver centre for further assessment.

7. Curative resection should incorporate complete mesocolic excision (analogous to total mesorectal excision, vide infra). Excise the colon, segmental blood supply and associated lymph nodes en bloc within an intact mesocolic fascial envelope. If you fail to dissect in this plane you increase the risk of dissemination of tumour cells, resulting in local recurrence.

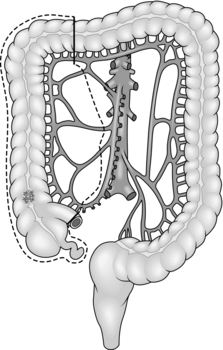

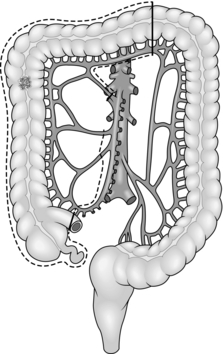

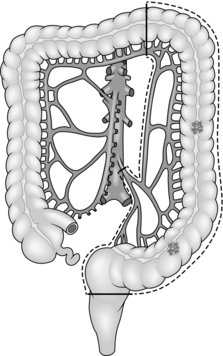

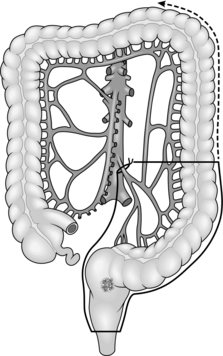

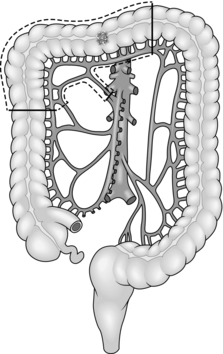

8. Treat carcinoma of the right colon by right hemicolectomy, taking the ileocolic pedicle at its origin from the superior mesenteric vessels (Fig. 13.1). For tumours of the hepatic flexure perform an extended resection, dividing the right branch of the middle colic pedicle at its origin (Fig. 13.2). If metastases are present perform a less radical resection without wide mesenteric clearance. Treat carcinoma of the transverse colon by extended right hemicolectomy or transverse colectomy (Fig. 13.3), mobilizing the hepatic and/or splenic flexure as required.

Fig. 13.3 Transverse colectomy.

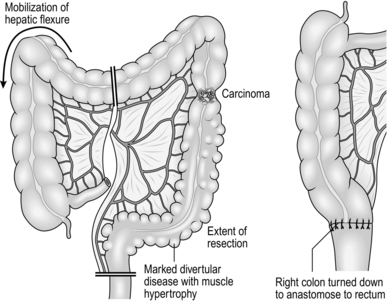

9. Treat carcinoma of the splenic flexure with left hemicolectomy, dividing the left colic pedicle at its origin (Fig. 13.4). If distal diverticular disease is present, perform an extended left hemicolectomy and swing the transverse and right colon down the right side of the abdomen to anastomose it to the rectum (Fig. 13.5). Alternatively, perform a subtotal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis.

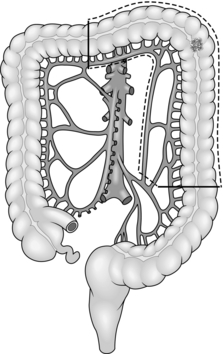

10. Treat carcinoma of the descending or sigmoid colon by left hemicolectomy, dividing the inferior mesenteric artery at its origin from the aorta and the inferior mesenteric vein at the same level (Fig. 13.6).

11. The surgical management of rectal carcinoma has undergone radical evolution over the last 20 years. Most cases of carcinoma of the rectum are now treated by restorative anterior resection using either a sutured, stapled or per-anal anastomosis. Abdominoperineal excision of the rectum and anus is required in around 20% of cases when it is impossible to obtain adequate distal clearance of the tumour. Carefully dissect in the pelvis to remove the mesorectum without breaching the fascial plane in which it is contained. Preserve the hypogastric nerve plexus if it is uninvolved with tumour, thereby reducing the incidence of erectile dysfunction and urinary complications. In expert hands total mesorectal excision (TME) results in very low local recurrence rates with an acceptable incidence of complications.

12. For high rectal carcinoma (tumours situated above the peritoneal reflection) with metastases, perform an anterior resection and primary anastomosis if you are able to perform this without the need for a defunctioning colostomy. These patients often have a limited survival and may never have the colostomy closed. For rectal carcinoma with unresectable local extension into the pelvic side wall, a Hartmann’s operation provides the best palliation.

DIVERTICULAR DISEASE

1. Diverticular disease is common and elderly patients having abdominal surgery are often found to have diverticula, most commonly in the sigmoid colon. Although diverticular disease may be pancolonic, symptoms usually result from muscle hypertrophy causing thickening and shortening of the sigmoid colon.

2. Indications for elective resection are rarely absolute. Consider surgery in patients in good general health who have severe episodes of left iliac fossa and suprapubic pain with marked diverticular disease on a barium enema or CT scan and who are unresponsive to dietary change and antispasmodic drugs. More definite indications for surgical treatment include:

Younger male patients (less than 50 years of age) with symptomatic disease, since statistically over 80% eventually come to surgery, many with complications

Younger male patients (less than 50 years of age) with symptomatic disease, since statistically over 80% eventually come to surgery, many with complications

Patients with urinary symptoms associated with their attacks or with pneumaturia, indicating a colovesical fistula. Female patients who have undergone hysterectomy may also present with offensive vaginal discharge secondary to a colovaginal fistula

Patients with urinary symptoms associated with their attacks or with pneumaturia, indicating a colovesical fistula. Female patients who have undergone hysterectomy may also present with offensive vaginal discharge secondary to a colovaginal fistula

Patients with recurrent attacks of acute diverticitis presenting with fever, and tenderness in the left iliac fossa or mass or evidence of a pericolic abscess on CT scan

Patients with recurrent attacks of acute diverticitis presenting with fever, and tenderness in the left iliac fossa or mass or evidence of a pericolic abscess on CT scan

Patients with recurrent lower gastrointestinal bleeding: surgery is not mandatory following a single episode of bleeding.

Patients with recurrent lower gastrointestinal bleeding: surgery is not mandatory following a single episode of bleeding.

3. Colectomy for diverticular disease is frequently more challenging than similar operations for cancer. Even elective resections may be associated with pericolic inflammation, oedema and pericolic abscess formation in the mesentery.

4. It is unnecessary to remove all the proximal diverticula. Resect the hypertrophied section of bowel (usually the sigmoid colon), with anastomosis between the descending colon and the upper third of the rectum at or below the sacral promontory.

5. The elective treatment of choice is primary resection and anastomosis. If there is acute inflammation at the time of surgery or the anastomosis is difficult, perform a temporary defunctioning ileostomy.

ULCERATIVE COLITIS

1. Offer elective surgery to patients with persistent bloody diarrhoea, anaemia, weight loss and general ill-health who do not respond to treatment with corticosteroids and immune modulators such as azothiaprine. The majority of these patients havepancolitis (Greek: pan = all, total). Patients with distal disease involving the rectosigmoid or left hemicolon can usually be managed medically. Try to operate on patients during a remission.

2. Active colitis of 10 or more years’ duration may result in epithelial dysplasia with eventual progression to carcinoma, even in the absence of any symptoms. These patients require yearly surveillance with colonoscopy and mucosal biopsy. Advise operation if they develop severe dysplasia. Advise colectomy on any patient with total colitis and a stricture on barium enema or colonoscopy. Steroid therapy is not a contraindication to surgery, but steroid cover is required during and after the operation.

3. In longstanding total colitis, the colon is thickened, shortened and featureless in appearance. The macroscopic appearances may vary with parts of the colon appearing more actively inflamed with thickening, oedema and marked hyperaemia. The paracolic and mesenteric nodes may be enlarged.

4. The simplest operation is a proctocolectomy with a conventional end (Brooke) ileostomy, which removes all the inflamed bowel and potential cancer risk in one procedure.

5. Consider alternative procedures:

If you are inexperienced in pelvic surgery, carry out a colectomy and ileostomy, retaining the whole rectum, and refer the patient to a specialist centre for subsequent reconstruction. This is also the procedure of choice in the urgent or emergency situation.

If you are inexperienced in pelvic surgery, carry out a colectomy and ileostomy, retaining the whole rectum, and refer the patient to a specialist centre for subsequent reconstruction. This is also the procedure of choice in the urgent or emergency situation.

In patients wishing to avoid a permanent ileostomy, perform a restorative proctocolectomy, preserving the anal canal and sphincters, and create an ileo-anal reservoir.

In patients wishing to avoid a permanent ileostomy, perform a restorative proctocolectomy, preserving the anal canal and sphincters, and create an ileo-anal reservoir.

In older or obese patients who wish to avoid a stoma but in whom the risks and uncertainties of pouch surgery do not seem justified, consider performing a colectomy and ileorectal (or if possible ileosigmoid) anastomosis. To achieve the best functional results, operate early in the course of the disease when the rectum is still distensible and there is no dysplasia present in rectal biopsies.

In older or obese patients who wish to avoid a stoma but in whom the risks and uncertainties of pouch surgery do not seem justified, consider performing a colectomy and ileorectal (or if possible ileosigmoid) anastomosis. To achieve the best functional results, operate early in the course of the disease when the rectum is still distensible and there is no dysplasia present in rectal biopsies.

The Kock reservoir is a continent ileostomy designed to spare patients the need to wear a stoma appliance. It is prone to complications and poor function and is, as a result, now rarely performed.

The Kock reservoir is a continent ileostomy designed to spare patients the need to wear a stoma appliance. It is prone to complications and poor function and is, as a result, now rarely performed.

CROHN’S DISEASE

1. This can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus and is primarily treated medically.

2. Resort to surgery if medical treatment fails to control the disease, or for complications such as stricture causing obstructive symptoms, abscess or fistula formation.

3. All or part of the colon may be involved in Crohn’s disease. At laparotomy or laparoscopy carefully exclude disease in the stomach, duodenum and small bowel. Measure and record the sites and extent of disease and the length of residual small bowel following resection: patients with Crohn’s disease may require multiple operations and may develop short bowel syndrome if surgery is not carefully planned.

4. Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum or ileocaecal region should be treated by ileocaecal resection, removing only the diseased segment: there is no advantage to removing macroscopically normal bowel. If there is a chronic abscess cavity in the right iliac fossa, position the anastomosis in the upper abdomen away from the inflamed tissues.

5. For extensive colitis unresponsive to medical treatment, perform a colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis or a total proctocolectomy and ileostomy. Stenosing or fistulating disease involving only the rectum may require abdominoperineal excision with an end colostomy.

6. Segmental colonic resection is appropriate for localized segmental involvement of the colon, or to treat internal fistula between the terminal ileum and the transverse or sigmoid colon.

POLYPS AND POLYPOSIS

1. Rectal polyps found at rigid sigmoidoscopy should be biopsied. If the polyp proves to be an adenoma, arrange a colonoscopy to find and remove any proximal polyps. Sessile villous adenomas usually occur in the rectum and can be removed by endoanal local excision. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEMS) and endoscopic laser ablation (useful in the frail and elderly) are available in specialist centres.

2. If large colonic polyps are present in a patient undergoing surgery for carcinoma, extend the resection to include them or consider subtotal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis.

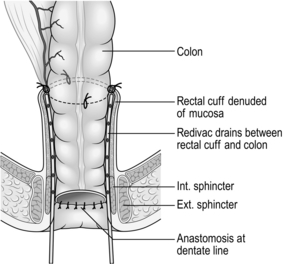

3. Circumferential villous adenomas of the rectum are at high risk of malignant change and are difficult to resect peranally. Perform anterior resection with colo-anal anastomosis or a modified Soave procedure, particularly for tumours extending more than 10 cm from the anus.

4. Surgery is mandatory in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) to avoid inevitable malignant change. Options include colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis or proctocolectomy and ileoanal pouch reconstruction. Following ileorectal anastomosis the rectum still carries the potential for malignant change. Inspect sigmoidoscopically every 6–12 months with fulguration of polyps over 5 mm in diameter.

URGENT OPERATIONS

1. Urgent operations on the colon or rectum are required for obstruction, perforation, acute fulminant colitis and, less frequently, life-threatening acute haemorrhage.

2. Stabilize the patient’s condition prior to surgery by replacing blood, fluid and electrolyte losses. Give broad-spectrum antibiotics (co-amoxiclav or a cephalosporin with metronidazole) to counteract sepsis.

3. Major abdominal sepsis, perforation or torrential haemorrhage demand operation as soon as the patient’s condition allows. Patients with colonic obstruction or inflammatory bowel disease rarely require immediate surgery and frequently benefit from appropriate investigation and resuscitation.

OBSTRUCTION

1. Establish the site of obstruction with a CT scan or water-soluble contrast enema.

2. If the patient is unfit for surgery, a stenosing tumour may be suitable for radiological stenting to open up the bowel lumen, allowing the patient’s condition to be optimized for subsequent elective surgery. Stenting is less successful for benign strictures due to diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease or external compression and carries a higher morbidity: a defunctioning proximal stoma provides better palliation in patients who are unfit for major surgery.

3. Urgent resection should be as radical as would be achieved electively, provided the patient’s condition permits this. If metastases are present, undertake a less radical resection if possible, as this will give better palliation.

4. Perform a right hemicolectomy for carcinoma of the right colon causing acute intestinal obstruction. It is rare to find a proximal tumour that is not resectable. Avoid a bypass operation if possible as this may relieve the obstruction but it will not stop bleeding from the tumour and consequent anaemia, nor will it palliate pain or complications resulting from invasion of other structures.

5. Historically, left-sided obstruction was treated by a three-stage procedure with an initial proximal stoma to relieve the obstruction, subsequent resection and anastomosis and, when the anastomosis was healed, closure of the stoma. Obstructing carcinoma of the sigmoid or descending colon is now usually treated by a one-stage colectomy with ileosigmoid or ileorectal anastomosis (Fig. 13.7). If a left-sided tumour is unresectable, create a proximal defunctioning colostomy.

6. Treat carcinoma of the rectosigmoid junction or rectum by resection and primary anastomosis with or without a defunctioning ileostomy. Alternatively, perform a Hartmann’s procedure (vide infra).

7. Acute obstruction due to diverticular disease is often complicated by paracolic abscess formation, and is most commonly treated by Hartmann’s procedure. However, if the infection is localized and can be completely excised then primary resection and anastomosis, with or without a defunctioning ileostomy, may be appropriate.

PERFORATION

1. Perforation of a carcinoma or diverticular disease requires resection and anastomosis with a covering stoma; if major faecal contamination is present, perform a Hartmann’s procedure.

2. If CT scanning demonstrates a localized perforation and pericolic abscess, drain it percutaneously. Operate if initially localized abdominal signs become more generalized or if the infection fails to settle despite adequate conservative therapy. Generalized purulent peritonitis secondary to diverticulitis may be managed by laparoscopic peritoneal lavage and drainage, provided there is no evidence of a free perforation. In patients with more extensive contamination and a free perforation, resection and primary anastomosis is possible in selected cases, but do not perform this in the presence of faecal peritonitis.

3. Primary anastomosis is increasingly popular because:

Patients require one operation rather than two

Patients require one operation rather than two

Following Hartmann’s procedure many patients are left with a permanent stoma, because they are unwilling or unfit to have further surgery

Following Hartmann’s procedure many patients are left with a permanent stoma, because they are unwilling or unfit to have further surgery

Reversal of Hartmann’s procedure can be challenging, particularly if attempted too early.

Reversal of Hartmann’s procedure can be challenging, particularly if attempted too early.

4. Always aim to resect the perforated segment of bowel, even in an acutely ill patient, to minimize the risk of persistent contamination. Also, it is difficult at operation to decide whether a lesion is a perforated carcinoma or diverticular phlegmon: up to 25% of patients with a preoperative diagnosis of perforated diverticulitis will prove to have malignancy. If carcinoma is suspected perform a radical resection: examination of the resected specimen in theatre may help to confirm the diagnosis.

ACUTE INFLAMMATORY OR ISCHAEMIC BOWEL DISEASE

1. Treat acute fulminant colitis, with or without toxic megacolon, by colectomy and ileostomy. Do not excise the rectum. It is usually safe to close the rectal stump but if it is very inflamed or friable you may need to bring it out as a mucous fistula. Alternatively, close the stump directly under the wound so that if it breaks down it will not contaminate the peritoneal cavity.

2. In ischaemic colitis, excise the segment of acutely ischaemic colon and create a proximal (and if necessary a distal) colostomy. Do not remove the rectum or distal sigmoid colon as these usually recover sufficiently for an anastomosis to be carried out later.

ACUTE MASSIVE HAEMORRHAGE

1. If possible, determine the site of bleeding by sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and angiography. In patients with episodes of haemorrhage and diverticular disease do not assume causation: 50% have another cause for the bleeding.

2. It is usually possible to arrest life-threatening bleeding by interventional radiology and embolization, which carries a much lower morbidity and mortality than emergency colectomy. Surgery may still be required if the embolized segment becomes ischaemic, but at least you will be sure which part to remove.

PRINCIPLES OF COLECTOMY

Appraise

1. Morbidity and mortality following colonic surgery are higher than following small bowel resection. Infection is more common, resulting in abscess formation with potentiation of collagenase activity which predisposes to anastomotic dehiscence.

2. In addition, the colonic blood supply is more tenuous and tissue perfusion may be suboptimal postoperatively, resulting in ischaemia to the anastomosis. If available, we recommend goal-directed intra-operative fluid replacement using peroperative transoesophageal Doppler monitoring.

Prepare

1. Enhanced recovery protocols (‘fast track surgery’) have demonstrated reduction in both morbidity and length of stay following elective colorectal resections. They typically include:

Avoidance of mechanical bowel preparation (vide infra)

Avoidance of mechanical bowel preparation (vide infra)

Preoperative carbohydrate loading to prevent the development of a catabolic state and insulin resistance

Preoperative carbohydrate loading to prevent the development of a catabolic state and insulin resistance

The use of minimally invasive surgery or small incisions

The use of minimally invasive surgery or small incisions

Goal-directed fluid replacement (vide supra)

Goal-directed fluid replacement (vide supra)

Prevention of intra-operative hypothermia

Prevention of intra-operative hypothermia

Avoidance of opiates by the use of epidural anaesthesia, transversus abdominis plane (TAPP) blocks or wound catheters to infuse local anaesthetics

Avoidance of opiates by the use of epidural anaesthesia, transversus abdominis plane (TAPP) blocks or wound catheters to infuse local anaesthetics

Avoidance or early removal of nasogastric tubes, drains and urinary catheters

Avoidance or early removal of nasogastric tubes, drains and urinary catheters

2. There is no evidence to support the routine use of bowel preparation before elective colonic operations and good evidence that the resulting fluid and electrolyte imbalances delay postoperative recovery. Some surgeons nonetheless prefer to prepare the left colon, but there is no need to clear the bowel prior to right hemicolectomy. Always prepare the bowel prior to low anterior resection with a loop ileostomy, as this will otherwise leave a long segment of faecally loaded colon between the covering stoma and the anastomosis. Sodium picosulfate and magnesium citrate (Picolax™, Citrafleet™), sodium phosphate (Fleet™) and polyethylene glycol (Kleanprep™, Moviprep™) are all suitable. Encourage adequate oral fluids during bowel preparation: intravenous fluids may be required in elderly patients. Patients likely to have a transanal stapled anastomosis should have an enema prior to surgery to avoid the problem of a rectum loaded with stool.

3. Give preoperative prophylactic antibiotics at induction of anaesthesia: a cephalosporin or a broad-spectrum penicillin plus beta-lactamase inhibitor (co-amoxiclav) plus metronidazole are suitable. Give a second dose of antibiotics if the duration of operation is more than 2 hours or if there is significant intraoperative contamination. There is no evidence that routine use of more than one dose of prophylactic antibiotics reduces the risk of infection, unless gross faecal contamination is present, when antibiotics should be continued for several days postoperatively.

4. Catheterize the patient after induction of anaesthesia and monitor urinary output during and after surgery.

Action

1. Clamp the segment of bowel to be resected with Parker-Kerr clamps or use a cross-stapling technique. Do not clamp the ends to be sutured: apply non-crushing clamps 5 cm away from the bowel end to avoid contamination while constructing the anastomosis.

2. A good blood supply is crucial to anastomotic healing. Ensure that both limbs of the anastomosis are pink and well perfused: visible or palpable pulsation in the mesenteric vessels is an added reassurance, as is pulsatile flow on dividing the marginal artery whilst preparing the bowel for anastomosis.

3. Divide the colon at right-angles to the mesentery. If there is disparity in size between the ends, particularly when carrying out a right hemicolectomy or an ileorectal anastomosis, make a slit in the antimesenteric border of the ileum until the two ends approximate in size. Alternatively, carry out a stapled side-to-side anastomosis. When anastomosing a long proximal limb of mobilized colon to the rectum check that it is not twisted through 360°. Clean the ends of the bowel to be sutured with swabs moistened in aqueous 10% povidone-iodine solution.

4. Suture the bowel using a single-layer seromuscular suture such as 3/0 PDS (polydioxanone sulphate) using either an interrupted or continuous technique. Invert the edges to ensure no mucosa protrudes from the suture line. Where the two bowel limbs are sufficiently mobile and well perfused a side-to-side stapled anastomosis is a quick and reliable technique, although significantly more expensive. This technique is ideally suited to small bowel and right colonic resections, but should be used with caution in the left colon where the blood supply is more tenuous.

5. Colorectal anastomosis is most easily accomplished using a circular stapling device such as the CEEA stapler, using a 28-or 31-mm diameter device. We particularly recommend it for anastomosis low in the pelvis where suturing may be technically difficult.

6. Prevent contamination of the operative field by placing a non-crushing clamp across the bowel 10 cm from the end before this is swabbed out and cleaned. Isolate the anastomosis from the peritoneum and wound edges while it is being constructed, using disposable drapes or abdominal packs soaked in 10% aqueous povidone-iodine solution. On completion of the anastomosis, discard any soiled packs and instruments and change gloves before closing the abdomen.

7. Intra-peritoneal drains are of no proven value and may actually increase the risk of anastomotic leakage. Some surgeons prefer to drain the pelvic cavity following low anterior resection or abdominoperineal excision.

LAPAROSCOPIC COLECTOMY

1. The indications for laparoscopic colectomy are essentially the same as for open surgery. The laparoscopic approach is associated with some short-term benefits when compared with open surgery, notably faster recovery and reduced postoperative pain and wound infection. Data from randomized trials have demonstrated oncological outcomes comparable to open surgery.

2. Like other advanced laparoscopic procedures, laparoscopic colectomy is associated with a steep learning curve, requiring around 30 resections to achieve competence. Mobile lesions in the right colon or rectosigmoid junction are ideal for the novice. Lesions in the upper sigmoid or descending colon which necessitate splenic flexure mobilization and mid or low rectal tumours, which require pelvic dissection, require considerably more skill and experience.

3. Patient-related factors such as obesity and previous abdominal operations can make laparoscopic surgery more difficult, although conversely laparoscopic colectomy may result in greater short-term benefits in these patients. Patients with compromised cardiopulmonary function require special attention as they tolerate prolonged pneumoperitoneum poorly: close liaison with an experienced anaesthetist is recommended. Patients with locally advanced disease (tumours with fixation to surrounding structures or contiguous organ involvement) should be selected with extreme caution. Such tumours often preclude a pure laparoscopic approach (although you may employ a ‘hand-assisted’ laparoscopic approach with the use of hand-access devices) and are better managed through a conventional laparotomy incision.

4. As abdominal organs cannot be palpated during laparoscopy, preoperative colonoscopy and imaging studies are important both for tumour localization and disease staging. If preoperative colonoscopy is incomplete, either barium enema examination or CT virtual colonoscopy should be considered for proximal colonic evaluation; the latter also facilitates better patient selection by providing information on tumour staging.

5. ‘Tattoo’ small mucosal lesions during endoscopic examination to facilitate identification at subsequent laparoscopy. Alternatively, carry out perioperative colonoscopy, preferably with CO2 insufflation, during surgery.

6. Laparoscopic colectomy is never a single surgeon operation. Always use a dedicated team of at least two experienced surgeons and one camera assistant. Experienced anaesthetists, nurses and technicians who are familiar with the procedures, laparoscopic instruments and ancillary technology also form an integral part of the team. The operating theatre should accommodate staff and equipment in an unencumbered fashion. If possible, carry out laparoscopic colectomy in an integrated endo-laparoscopic operating suite where all equipment, including the optical system, energy source and monitors, is placed on ceiling-mounted platforms. Back-up equipment and facilities are essential.

7. Recommended instruments for laparoscopic colectomy:

Three to four atraumatic forceps for handling of bowel and fine tissues

Three to four atraumatic forceps for handling of bowel and fine tissues

Two grasping forceps for holding sutures or cotton tapes

Two grasping forceps for holding sutures or cotton tapes

Ultrasonic dissection device, 5 or 10 mm in size; or Ligasure™ device (Tyco Healthcare Group LP, Boulder, U.S.A.), 5 or 10 mm in size

Ultrasonic dissection device, 5 or 10 mm in size; or Ligasure™ device (Tyco Healthcare Group LP, Boulder, U.S.A.), 5 or 10 mm in size

Laparoscopic bipolar coagulating forceps (Gyrus Medical Limited, Cardiff, U.K.), 5 mm in size

Laparoscopic bipolar coagulating forceps (Gyrus Medical Limited, Cardiff, U.K.), 5 mm in size

Endoscopic clip applicators and clips

Endoscopic clip applicators and clips

Endo-staplers of various sizes, used for bowel transection (blue, gold or green cartridge) and vascular division (white cartridge)

Endo-staplers of various sizes, used for bowel transection (blue, gold or green cartridge) and vascular division (white cartridge)

Circular staplers for trans-rectal bowel anastomosis

Circular staplers for trans-rectal bowel anastomosis

A sterile plastic zip-lock bag, used as a parietal protector during specimen retrieval.

A sterile plastic zip-lock bag, used as a parietal protector during specimen retrieval.

RIGHT HEMICOLECTOMY

Appraise

1. Perform this operation for carcinoma of the caecum and ascending colon, benign tumours of the right colon, perforated caecal diverticulum, midgut neuroendocrine tumours and carcinoma of the appendix. Small, low-grade neuroendocrine tumours of the tip of the appendix (appendiceal carcinoid) found incidentally at appendicectomy do not require subsequent hemicolectomy.

2. In benign disease of the terminal ileum, particularly Crohn’s disease, resect the diseased ileum together with the caecum and 2–3 cm of the right colon. If ileocaecal Crohn’s disease is associated with abscess formation in the right iliac fossa, place the anastomosis in the upper abdomen away from the abscess cavity to reduce the risk of postoperative fistula formation.

3. Do not site a small bowel anastomosis close to the ileocaecal valve, as this may predispose to anastomotic leakage. It is preferable to remove the caecum and a small part of the ascending colon to achieve an ileocolic anastomosis.

4. In patients with distal colonic obstruction the caecum may be ischaemic: include any non-viable bowel in the resection, either by means of an extended right hemicolectomy or subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis.

Action

Resect

1. Make a midline incision centred on the umbilicus or a transverse incision extending laterally from the umbilicus. Handle the tumour as little as possible. If the serosa is infiltrated by carcinoma, cover it with a swab soaked in aqueous 10% povidone-iodine solution.

2. Draw the caecum and ascending colon medially. Divide the parietal peritoneum in the lateral paracolic gutter from the caecum to the hepatic flexure. If the carcinoma infiltrates the lateral abdominal wall do not attempt to dissect it off, but excise a disc of peritoneum and underlying muscle en-bloc with the specimen.

3. Dissect the plane between the right colon and posterior abdominal wall, identifying and preserving the right gonadal vessels, ureter and duodenum.

4. Mobilize the hepatic flexure and posterior attachments of the terminal ileum so that the whole of the right colon can be lifted medially and out of the abdomen.

5. Clamp and divide the ileocolic artery and vein close to their origin from the superior mesenteric vessels, being careful not to tent the superior mesenteric trunk up and thereby inadvertently damage it. Divide the right colic vessels (if present) and the right branch of the middle colic vessels close to their origin.

6. The extent of the resection depends on the size and site of the tumour but normally extends from terminal ileum to the mid-transverse colon. In operations for carcinoma of the right colon it is not necessary to resect more than a few centimetres of terminal ileum.

7. Remove the right half of the greater omentum with the specimen. If the tumour is situated near the hepatic flexure remove the adjacent gastroepiploic vascular arcade to ensure adequate clearance.

8. Place a Parker-Kerr clamp or cross-stapler across the ileum and transverse colon at the site of division. If the patient is obstructed place towels around the bowel at the time of division as described above.

9. Divide the bowel proximally and distally and remove the specimen.

10. Hold the ends of the ileum and colon to be anastomosed in Babcock’s forceps and clean them with mounted swabs soaked in aqueous 10% povidone-iodine solution.

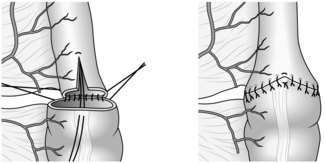

Unite

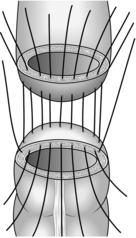

1. Construct a functional end-to-end anastomosis using a linear cutting stapling device. Alternatively, suture the terminal ileum end-to-end to the transverse colon, if necessary widening the ileum with a Cheatle antimesenteric slit, described by the English surgeon Sir George Cheatle, 1865–1951 (Fig. 13.8). Mark the anastomosis with radio-opaque clips if desired.

Fig. 13.8 Cheatle slit on antimesenteric aspect of the ileum to accommodate the discrepancy in size.

2. Appose the cut edges of the mesentery with a 2/0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) or 3/0 PDS suture.

3. Return the anastomosed bowel to the right paracolic gutter, covering it with the remaining omentum.

Technical points

1. Resections for benign conditions such as Crohn’s disease or caecal diverticulum should be conservative. Divide the vessels in the middle of the mesentery rather than at their origin.

2. If a carcinoma is locally invasive but can be excised radically, include abdominal wall or involved organs in the resection as required.

3. For carcinoma of the transverse colon you may need to mobilize the splenic flexure. This is best achieved by entering the lesser sac of the peritoneum through the gastrocolic omentum. Divide the middle colic vessels close to their origin and anastomose the terminal ileum to distal transverse colon, if adequately perfused, or else the descending or sigmoid colon.

4. If multiple metastases are present, a limited segmental resection provides better palliation than a bypass procedure.

Checklist

1. Make sure the anastomosis is viable and not under tension.

2. Examine the raw surfaces, particularly in the right paracolic gutter, for bleeding. Lavage the operative field with warm isotonic saline and remove any blood which may have collected above the right lobe of the liver and in the pelvis. Do not add antiseptics or antibiotics to the fluid as these irritate the peritoneum and promote adhesion formation.

LAPAROSCOPIC RIGHT HEMICOLECTOMY

Access

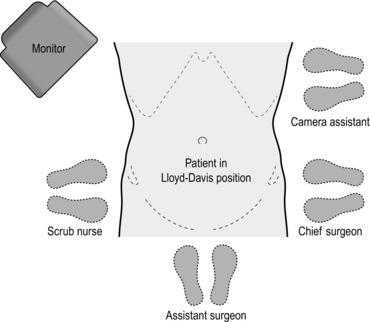

1. Stand on the left side of the patient. The monitor is placed next to the patient’s right shoulder (Fig. 13.9).

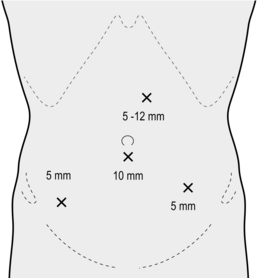

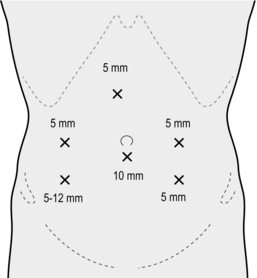

2. Establish pneumoperitoneum via a 10–11-mm subumbilical incision using an open technique. Place further ports as shown in Figure 13.10.

3. Place the patient in steep head-down position and rolled to the left so that the small bowel falls away from the pelvis, the caecum and terminal ileum. Re-position the patient into the head-up position as the operation field moves to the hepatic flexure and transverse colon.

Action

1. We describe the medial-first approach here. Identify first the ileocolic vessels near the third part of duodenum. Have the assistant surgeon hold up the caecum, putting the vascular pedicle on stretch. Divide the pedicle between endo-clips close to the duodenum (i.e. ‘high’ ligation). Take care to avoid inadvertent injury to the superior mesenteric artery and vein.

2. Continue the mesenteric division upwards above the second part of duodenum. Display the right colic vessels by gently lifting the mesentery upwards; avoid excessive traction, which may tear the right colic vein. Once identified, the right colic vessels, usually shorter and smaller than the ileocolic pedicle, are controlled and divided.

3. Blunt dissection (e.g. with the use of the closed jaws of a 10-mm Ligasure™) is then carried out laterally in the plane between the colonic mesentery and the retroperitoneum. The right ureter and gonadal vessels are identified beneath the retroperitoneal fascia. Perform dissection as far lateral as possible, till the lateral abdominal wall is reached. Lateral to the second part of duodenum, carry out similar blunt dissection to separate the ascending colon and its mesentery from Gerota’s fascia. Always keep the plane of dissection anterior to the duodenum at all times and do not Kocherise the duodenum. Perform blunt dissection as far upwards as possible; the inferior border of the liver is sometimes visible through the fascial covering at the end of dissection. The medial dissection is now complete.

4. Start the lateral dissection by incising the fascia inferio-lateral to the ileocaecal junction. Have the assistant surgeon pull the caecum cranially and medially to provide the necessary countertraction. Follow the ‘white line’ of Toldt’s fascia and mobilize, in this order, the terminal ileum, caecum and ascending colon. The right ureter and gonadal vessels are identified once again under the retroperitoneal fascia.

5. Next, place the table in head-up position to keep the small bowel away from the upper abdomen. Starting at proximal to mid transverse colon, incise the greater omentum close to the colon and enter the lesser sac, caution being taken not to damage the colonic wall or transverse mesocolon. When the lesser sac is entered the posterior wall of the stomach should be clearly visible. Follow the upper border of the transverse colon and continue the division of the greater omentum and fascia towards the hepatic flexure. Have the assistant retract the hepatic flexure medially and caudally to provide countertraction. Divide the final fascial attachments near the hepatic flexure. The duodenum is again identified underneath the colon. The intra-corporeal stage of the operation is now complete.

6. Finally, pneumoperitoneum is abolished for extra-corporeal resection and anastomosis. The 5–12-mm epigastrium port is extended and shielded with a plastic bag or wound protector. The tumour is delivered and excised through this protected wound. Ileo-transverse anastomosis is performed using either a hand-sewn or stapled technique.

LEFT HEMICOLECTOMY

Appraise

1. Undertake left hemicolectomy for tumours of the left and sigmoid colon, sigmoid volvulus and diverticular disease.

2. If the operation is for an obstructing neoplasm, carry out an extended colectomy with an ileosigmoid or ileorectal anastomosis. Alternatively, carry out a resection with on-table decompression or irrigation of the obstructed proximal colon and primary anastomosis. Try to avoid Hartmann’s procedure as patients are often unfit or reluctant to undergo a further reversal operation.

3. In diverticular disease, resect the sigmoid colon and as much of the rectum and descending colon as is necessary, whilst avoiding potential tension on the anastomosis. Isolated diverticula in the descending and transverse colon can safely be left, providing the bowel wall is not thickened. Anastomose the proximal bowel to the rectum at or below the sacral promontory.

4. Mobilization of the splenic flexure and the left half of the transverse colon is required for tumours of the descending colon, but may not be necessary for a tumour in the mid or lower sigmoid colon.

Prepare

Assess

1. If the operation is for a carcinoma, palpate the liver for occult metastases, examine the colon and entire small bowel, look for enlarged mesenteric and para-aortic nodes and examine the peritoneal cavity and pelvis for metastases.

2. Assess the mobility of the carcinoma; if the serosal surface is involved, cover it with a swab soaked in 10% aqueous povidone-iodine solution.

3. If you are performing colectomy for a benign condition, assess the diseased colon to decide the extent of resection.

Resect

1. Divide the congenital adhesions that bind the sigmoid colon to the abdominal wall in the left iliac fossa and then divide the lateral peritoneum in the paracolic gutter, following the ‘white line’, which represents the conjunction of posterior and visceral peritoneum.

2. If required, mobilize the splenic flexure by dividing the phrenocolic ligament. Avoid damaging the spleen and the tail of the pancreas. If the carcinoma is distal, preserve the greater omentum by dividing the adhesions between the omentum and the colon proximally to the middle of the transverse colon and entering the lesser sac. If the tumour is situated near the flexure, divide the left side of the gastroepiploic vascular arcade and excise the lesser and greater omentum with the specimen.

3. Elevate the left colon on its mesentery and separate it from the duodeno-jejunal flexure, left ureter and gonadal vessels using blunt dissection.

4. Incise the peritoneum medial to the colon and separate the inferior mesenteric artery from the sacrum by gentle blunt dissection. Create a window in the mesentery and trace the artery proximally. Clamp, ligate and divide the artery close to its origin. Identify the inferior mesenteric vein lying laterally and clamp, ligate and divide it below the lower border of the pancreas.

5. Divide the mesentery and marginal vessels at the chosen proximal and distal resection sites.

6. Place a non-crushing right-angled clamp across the rectosigmoid junction and irrigate the rectum with 10% povidone-iodine solution via a catheter passed through the anus until it is clean. This cytotoxic washout removes any viable tumour cells that may otherwise implant in the anastomotic line.

7. Prepare the proximal colon for division by placing a non-crushing clamp across the bowel proximal to the intended site of division. Cross-staple or use a Parker-Kerr clamp just distal to the intended site of division. Divide the colon, hold the proximal end in Babcock’s forceps and swab the bowel lumen with aqueous 10% povidone-iodine solution.

8. Divide the rectosigmoid below the right-angled clamp and remove the specimen comprising the left hemicolon, inferior mesenteric pedicle and the whole of the mesentery. Do not divide the sigmoid higher than 10 cm above the rectosigmoid junction or you will leave an ischaemic segment distally.

LAPAROSCOPIC LEFT HEMICOLECTOMY

Access

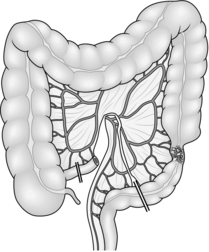

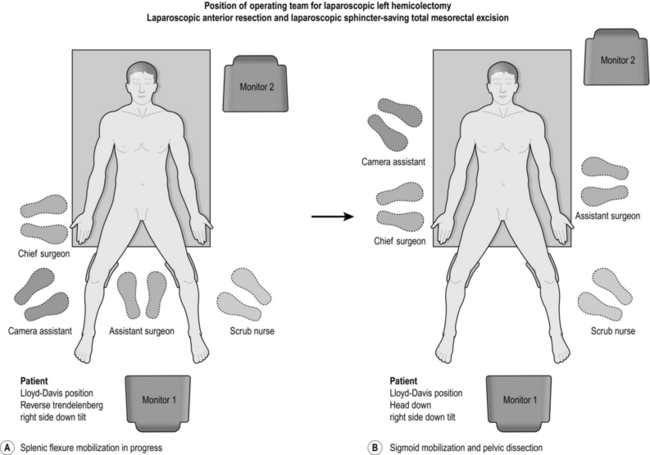

1. Stand on the right side of the patient, facing the monitor at the table end. A second monitor is positioned as shown for the assistant (Fig. 13.12).

2. Place the ports as shown in Figure 13.13.

3. Put the patient in a steep head-down position with the table rotated to the right, a position that allows the small bowel to fall away from the left lower quadrant and the pelvis.

Action

1. Splenic flexure mobilization is carried out first, once the tumour is judged to be resectable: the medial-to-lateral approach is described here. The small bowel is kept in the right side of the abdomen by tilting the operating table to the right (right side down position). The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) is identified lateral to the duodeno-jejunal flexure, and is controlled and divided with the Ligasure™. Using the same device, blunt dissection is carried out in the avascular plane between the descending colon mesentery and the retroperitoneal fascia. Continue this dissection laterally towards the splenic flexure as far as possible until Gerota’s fascia is exposed. The inferior border of the pancreas should be clearly evident: avoid dissecting deep to the pancreas. After completion of the medial dissection, start the lateral dissection at the mid-transverse colon. The greater omentum is peeled off the colon by incising the fascia just above the bowel, caution being taken to avoid damage to either colon or mesocolon. The posterior wall of the stomach should be clearly seen once the lesser sac is entered. By keeping close to the colon at all times, further dissection along the upper and lateral border will allow complete mobilization of the splenic flexure. Identify the pancreas once more and divide the attachment of the transverse mesocolon to its inferior border, taking care to avoid injury to the middle colic vessels. Sufficient mobilization is achieved when the splenic flexure can be swung to the midline. A head-up (reverse Trendelenburg) tilt helps improve exposure during the final stage of lateral dissection.

2. Debate continues as to whether a lateral or medial-first approach should be used for sigmoid colon mobilization and vascular control. The lateral-first approach is easier for the novice as it is the same as for open surgery and is described here.

3. Identify the left gonadal vessels and ureter under the retroperitoneal fascia in the left lateral peritoneal space. Now incise the retroperitoneal fascia medial to the ureter (beware of the iliac vein which lies deep to the ureter), and enter the presacral space in a plane anterior to the left presacral hypogastric nerve, which is located 1–2 cm lateral to the midline at the level of the sacral promontory. The lateral dissection is now complete.

4. Swing the sigmoid colon to the left side and incise the retroperitoneal fascia at the base of the sigmoid mesentery, starting at the level of the sacral promontory. Take care to avoid damage to the underlying right hypogastric nerve and right ureter. If adequate lateral dissection has been performed, a generous retromesenteric window is easily made at the base of the mesosigmoid, which should by now look paper-thin. Visualize the left ureter through this retromesenteric window. Continue to divide the mesosigmoid cranially, anterior to the aorta, until you encounter the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). Divide the IMA using a linear endo-stapler (white cartridge), clips or the Ligasure™ device: do not use the latter option in patients with extensive atherosclerosis and calcification as haemostasis may be suboptimal.

5. The medial mesenteric division is continued further cranially to join the previous window from the divided IMV. Divide the remaining posterior fascial attachments between the mesentery and the retroperitoneum. Following this, the whole left-side colon should be freely mobile. At a trial descent, the splenic flexure should reach the pelvis easily without tension. Divide the mesentery at the rectosigmoid with the Ligasure™, and after performing cytocidal lavage, transect the rectum with a linear endo-stapler (blue or green cartridge) at a level distal to the sacral promontory.

6. Abolish pneumoperitoneum, deliver the specimen and excise it via a 5–6 cm Pfannestiel incision protected with a sterile plastic bag. Use a muscle-splitting incision which is less painful than a muscle-cutting incision and results in fewer postoperative hernias. Check again that the colon is long enough to allow for a tension-free anastomosis low down in the pelvis, reaching the symphysis pubis extra-corporeally without tension. Secure the anvil of a circular stapler in the colonic stump with a purse-string suture. Replace the colon in the abdomen, and close the retrieval wound. Re-establish pneumoperitoneum and reposition the small bowel. Insert the circular stapler transanally and perform intra-corporeal anastomosis as for open surgery. Inspect the tissue doughnuts for completeness.

7. You may perform perioperative colonoscopy following construction of the anastomosis to carry out air-testing for leaks and inspect the anastomosis for staple line bleeding; confirm that the colonic mucosa is adequately perfused at the same time.

8. If the proximal or distal doughnuts are incomplete or the air-leak test is positive, drain the pelvis and create a covering stoma.

CARCINOMA OF THE RECTUM

Appraise

1. Confirm the diagnosis in all patients with sigmoidoscopy and biopsy, and evaluate the proximal colon with colonoscopy or CT colography.

2. If possible, perform magnetic resonance imaging in lower and middle third tumours to assess T and N stage and potential involvement of the circumferential resection margin (CRM). If MRI is not available, perform an examination under anaesthetic to assess the fixity of low tumours. Exclude distant metastases with CT chest, abdomen and pelvis.

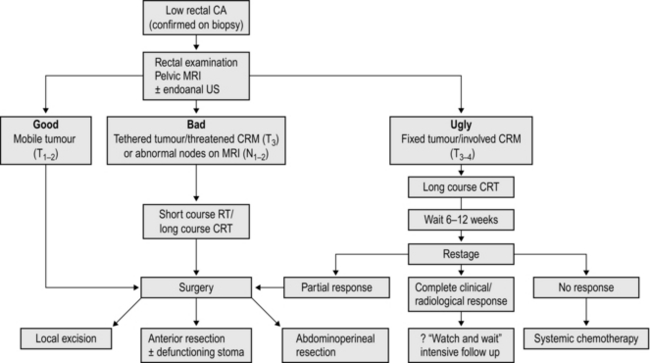

3. Short-course preoperative radiotherapy has been shown to reduce the risk of local recurrence following resection of rectal cancer, but this benefit must be weighed against poorer functional results following low anterior resection, impaired healing of the perineal wound following abdominoperineal resection and an increased risk of late malignancy. Consider radiotherapy in lower third tumours, particularly those sited anteriorly, fixed or tethered tumours and lesions staged T3 or T4 and those with a threatened CRM on MRI scanning. Long-course chemoradiotherapy is used to ‘downstage’ locally advanced, fixed rectal cancers. It may result in complete clinical and radiological resolution of the tumour: if so, a ‘wait-and-watch’ policy may be appropriate. The management of low rectal cancers is summarized in Figure 13.14.

4. If the patient presents as an emergency with obstructive symptoms or pain, perform a trephine colostomy (see below) and then undertake a full assessment and appropriate neoadjuvant treatment.

5. A few patients with small early carcinomas (T1 or T2 assessed by transrectal ultrasound) are suitable for a peranal local excision.

ANTERIOR RESECTION OF THE RECTUM

Action

1. Mobilize the left side of the colon by dividing the congenital adhesions as described for left hemicolectomy. Assess the length of colon required to achieve a tension-free anastomosis: if the planned proximal resection margin will reach to the pubic symphysis, it will reach to the pelvic floor.

2. If necessary, mobilize the splenic flexure and the left half of the transverse colon, preserving the omentum unless there are metastases present in it. Avoid damage to the spleen (Fig. 13.15).

3. Mobilize the left colon by pulling it to the right on its mesentery. Identify the left ureter and gonadal vessels and sweep them away from the mesocolon.

4. To enter the mesorectal plane lift the sigmoid loop vertically. Divide the peritoneum on the right side to expose the inferior mesenteric artery and follow it proximally to its origin and distally into the loose areolar tissue of the mesorectal plane. Push away the tissue containing the pelvic nerve plexus which lies deep to the vessels: both branches of the plexus should be visible as they divide around the rectum at the level of the sacral promontory.

5. Make a similar incision in the peritoneum of the left side to produce a window with artery above and nerves below. Clamp, divide and ligate the artery close to its origin from the aorta. If the patient is old and atherosclerotic, divide the pedicle further from the aorta, preserving the left colic artery. Divide the inferior mesenteric vein below the lower border of the pancreas. Select a suitable area to transect the proximal colon and divide the mesentery up to this point. Transect the bowel using a linear cutting stapler and pack the proximal colon and small bowel out of the way in the upper abdomen. The specimen can now be pulled anteriorly to facilitate the pelvic dissection.

6. The extent of rectal mobilization depends upon the level of the tumour. If it is below the peritoneal reflection, mobilize the rectum and mesorectum down to the pelvic floor.

7. Move to the left of the patient. Pull the rectum forwards to dissect the plane between presacral fascia and mesorectum from the sacral promontory to the tip of the coccyx. This is facilitated by an assistant using a St Mark’s lipped retractor to pull the rectum forwards whilst the operating surgeon carries out sharp dissection with scissors or diathermy. Take care to visualize and preserve the presacral nerves.

8. As the posterior dissection deepens, divide the peritoneum over each side of the pelvis, mid-way between the rectum and pelvic side-wall, uniting the incisions anteriorly in the midline 1 cm above the peritoneal reflection, overlying the seminal vesicles anterolaterally.

9. Hold the seminal vesicles forwards with a St Mark’s lipped retractor and dissect between the vesicles and the rectum to expose the rectovesical fascia, named after the Parisian anatomist and surgeon Charles Denonvilliers (1808–1872). Incise this and dissect distally in the male to the lower border of the prostate. In the female, dissect distally between the rectum and vagina as far down as necessary to achieve adequate mobilization of the tumour.

10. While retracting the rectum first to one side and then the other side of the pelvis, continue dissecting in the avascular plane between the mesorectum and pelvic side wall. If available, employ the Ligasure™ device or harmonic scalpel as a useful aid to bloodless dissection. Do not clamp and ligate the so-called ‘lateral ligaments’ as this may tent up and damage the third sacral nerve root, resulting in loss of sexual function in the male.

11. Lift the rectum and tumour out of the pelvis and select a suitable site for division of the rectum, if possible leaving a 5-cm clearance below the carcinoma. For lower third tumours this degree of clearance is not possible in a restorative procedure. Provided you have performed a total mesorectal excision, a 1 to 2-cm distal margin of rectum is sufficient to achieve a curative resection. For lesions of the upper rectum divide the mesorectum perpendicularly to the rectal wall at the level of resection using the Ligasure™, or divide it between mounted ligatures. Avoid oblique dissection, which may breach mesorectal tumour deposits. Apply a transverse stapler or right-angled clamp to the rectum at the site selected for division. Remember, if you are performing a stapled anastomosis an extra 8 mm of rectal wall is excised in the distal ‘doughnut’.

12. Irrigate the rectum through the anus with aqueous 10% povidone-iodine solution. If only a small cuff of sphincter and rectum remains, swab it out with the same solution.

13. Divide the rectum below the stapler or clamp with a long-handled scalpel. Remove the specimen containing the rectal carcinoma, the complete mesorectal envelope and inferior mesenteric pedicle.

Unite

Sutured anastomosis

1. Insert vertical mattress sutures into the posterior layer but do not tie them. Hold each suture with artery forceps until they have all been inserted (Fig. 13.16).

2. Have the sutures all held taut while you push down the proximal colon until its posterior edge is in contact with the rectum. This is the ‘parachute’ technique. Tie the sutures with the knots within the lumen. Hold the two most lateral sutures and cut the others. Suture the anterior layer using interrupted seromuscular inverting sutures, again inserting them all before tying them.

3. Radio-opaque clips may be used to mark the anastomosis if desired.

Stapled anastomosis

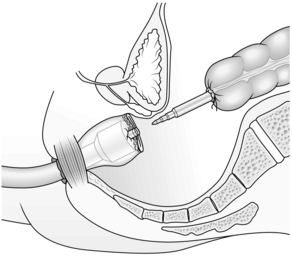

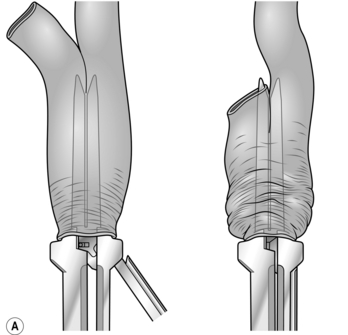

1. Low colorectal anastomosis is more easily accomplished using the CEEA circular stapling device. Carry out the operation exactly as described above but close the rectal stump using a cross stapler. Insert a 2/0 Prolene™ purse-string suture into the end of the proximal colon. Holding the bowel edges with Babcock’s forceps, insert the anvil of a 28-mm or 31-mm stapling gun and tie the purse-string suture as tightly as possible.

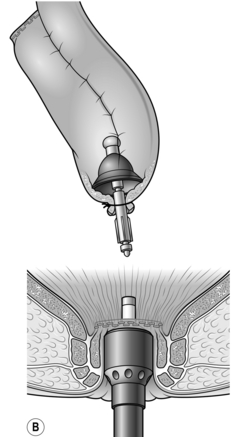

2. Introduce the body of the CEEA gun through the anus and open it, guiding the spike of the gun through the posterior aspect of the stapled rectal stump in the middle and just behind the staple line. Remove the spike if it is detachable and connect the anvil to the cartridge (Fig. 13.17).

3. Have the assistant operating the gun approximate the anvil to the cartridge while you ensure that the vaginal vault and any loops of small bowel are not trapped in the closing stapler. Fire the staple gun to construct the anastomosis. Open the gun two full turns to separate the anvil from the cartridge and rotate it 360o clockwise and again anti-clockwise to ensure the anastomosis is free before gently extracting it from the anus.

4. Check the integrity of the stapled anastomosis:

Examine the ‘doughnuts’ of colon and rectum removed from the gun. They should be complete. Identify the distal doughnut and send it for histological examination.

Examine the ‘doughnuts’ of colon and rectum removed from the gun. They should be complete. Identify the distal doughnut and send it for histological examination.

Perform a digital rectal examination to exclude any palpable abnormality.

Perform a digital rectal examination to exclude any palpable abnormality.

Fill the pelvis with saline and place a non-crushing clamp on the distal colon. Gently insufflate air into the rectum through a sigmoidoscope or bladder syringe: if no bubbles appear and the doughnuts are complete, the anastomosis is satisfactory.

Fill the pelvis with saline and place a non-crushing clamp on the distal colon. Gently insufflate air into the rectum through a sigmoidoscope or bladder syringe: if no bubbles appear and the doughnuts are complete, the anastomosis is satisfactory.

Checklist

1. Wash out the paracolic gutter with warm isotonic saline and make sure there is no bleeding, particularly in the region of the splenic flexure and spleen.

2. Check that the anastomosis is not under tension and that the proximal colon is viable.

3. Some surgeons prefer to drain the pelvis to prevent an infected pelvic haematoma, using a suction drain inserted through a stab wound in the left iliac fossa. Meticulous haemostasis is preferable.

4. Replace the small bowel and cover it with the omentum before closing the abdomen.

LAPAROSCOPIC ANTERIOR RESECTION

Assess

1. The position of the patient, surgical team and laparoscopic ports are similar to those for laparoscopic left hemicolectomy (see Figs 13.12, 13.13). If splenic flexure mobilization is not required, omit the 5-mm right upper quadrant port.

2. Throughout the procedure place the patient in a 20o Trendelenburg position with a right-side-down tilt, a position that helps to clear the small bowel off the lower abdomen and pelvis.

ACTION

1. In a female patient, hitch up the uterus by passing sutures (OO Prolene on a straight needle) underneath the two fallopian tubes near the uterine cornu and tying them to the lower anterior abdominal wall. The stitch should pass through the skin and be tied over a piece of gauze as a reminder to the surgeon to replace the uterus at the end of operation.

2. Splenic flexure mobilization is rarely required for ‘high’ anterior resection, as long as the sigmoid colon is healthy and can be brought down to the pelvis for a tension-free anastomosis after mobilization. When the sigmoid colon is diseased, as from severe diverticular disease or previous radiotherapy, or becomes ischaemic following high ligation of the IMA (as occasionally arises in elderly patients with extensive atherosclerosis), it is preferable to use the descending colon for anastomosis. In this case proceed to splenic flexure mobilization as previously described.

3. Carry out sigmoid mobilization and vascular control as previously described for laparoscopic left hemicolectomy.

4. Retract the rectum upwards and forwards, and identify the loose areolar plane between the mesorectum and the presacral fascia, with the hypogastric nerves lying on it. Continue dissection of the presacral space posteriorly and laterally, using a combination of sharp and blunt dissection in a similar manner to open surgery. Slowly divide the posterior mesorectum 5 cm distal to the tumour, using an ultrasonic dissector or Ligasure,™ until you expose the rectal tube. Have the assistant pull the rectum in a cephalad direction. Following cytocidal lavage through the anus transect the rectum with a linear endo-stapler (blue or gold cartridge). Two to three firings are sometimes required, and an angulating stapler works better in the lower pelvis. Perform a trial descent to confirm that there is a sufficient length of colon for anastomosis.

5. Undertake laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) for cancers in the mid and low rectum. After initial posterior and lateral dissection, pull the rectum in a cephalad direction to expose the rectovesical or rectouterine pouch. Then incise the anterior peritoneal refection. Proceed with the anterior dissection as in open surgery, in male patients between the rectum and Denonvillier’s fascia covering the seminal vesicles and in females between the rectum and upper vagina. Have the assistant insert a finger into the vagina, retracting it upward, to help with dissecting the rectovaginal plane. Facilitate the posterior dissection distally by turning the 30° laparoscope 180° upwards. Continue the dissection laterally until the whole rectum is mobilized distally down to the pelvic floor. After cytocidal lavage divide the rectum with an endo-stapler just above the pelvic floor. A smaller size stapler (30 mm) works better in the restricted space of the true pelvis but several firings may be required. A blue cartridge gives the best haemostasis, but in patients who have received neoadjuvant radiotherapy the tissues are thicker and more oedematous and it may be preferable to use a greater staple height (gold or green cartridge). After rectal transection perform a trial descent as described above.

6. Specimen retrieval and intra-corporeal anastomosis are performed as described for laparoscopic left hemicolectomy. In low anterior resection be extremely cautious to avoid inadvertent stapling of the levator muscles or adjacent structures. In female patients, the assistant surgeon lifts the vagina upwards with a finger while closing the circular stapler; this manoeuvre helps to exclude the vaginal vault from the anvil and prevent an unintentional rectovaginal fistula.

7. Either a side-to-end anastomosis (L-pouch) or a colonic J pouch can be constructed to improve subsequent bowel function. For colonic J pouch, fashion a 5-cm long pouch with a 60-mm linear cutter, using either the descending or the proximal sigmoid colon. Secure the detachable anvil of a circular stapler into the apex of the pouch with an O Prolene string suture. Put the pouch back into the peritoneal cavity, and close the incision in layers.

8. We recommend a covering stoma following TME to guard against the relatively high rate of anastomotic leakage, which is 20% or more. Either loop ileostomy or transverse loop colostomy is suitable, but loop ileostomy is easier to create and close subsequently. Identify a point in the terminal ileum about 20 cm from the ileocaecal valve for the formation of a loop ileostomy. Mark the antimesenteric border lightly with bipolar cautery at two different points to differentiate the proximal and distal limbs. Tie a cotton tape around this segment via a mesenteric window, and retract the ileal segment by grasping the cotton tape, taking care to ensure that the ileum is not twisted during extraction. Since the patient has been in a right-side down position, make sure no small bowel loops are trapped in the lateral space. Abolish the pneumoperitoneum and raise a covering ileostomy over the premarked stoma site. If desired, drain the presacral space via the left lower quadrant 5-mm port.

Aftercare

1. A nasogastric tube is occasionally required to deflate the stomach for better exposure of the transverse colon and splenic flexure. Remove it at the end of the operation before the reversal of anaesthesia.

2. Whilst postoperative feeding can be started as early as the day of operation, it is usually more sensible to start oral intake on the first postoperative day if there is no evidence of nausea or abdominal distension.

HARTMANN’S OPERATION

Appraise

Action

1. Close the distal rectum, ideally with a cross-stapler. If the rectum is divided low down in the pelvis and the end is difficult to suture or staple, leave it open and insert a drain through the anus into the pelvis.

2. Bring out an end colostomy as described below under abdominoperineal excision of the rectum.

ABDOMINOPERINEAL EXCISION OF THE RECTUM

Prepare

1. Ask the stomatherapist to mark the ideal position for the stoma on the skin of the left iliac fossa: this will depend on the patient’s body habitus and should be assessed lying, sitting and standing to ensure that the stoma appliance stays in place.

2. This operation may be carried out using a synchronous combined approach with two teams of surgeons, but is better performed by one experienced surgical team carrying out the abdominal and perineal parts sequentially.

3. Do not give the patient preoperative bowel preparation; it is difficult to construct a perfect end colostomy in the presence of liquid stool.

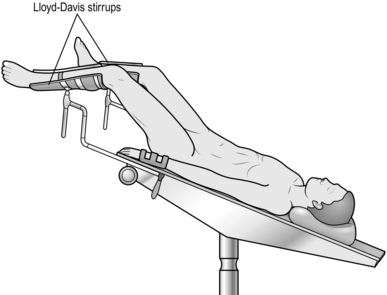

4. Place the patient in the lithotomy Trendelenburg position. Rest the sacrum on a pad to allow the coccyx to overhang the end of the table.

6. Strap up the scrotum so that it is clear of the perineal operative field.

7. Perform a digital rectal examination to determine the distance of the carcinoma from the anal verge and its fixity to pelvic structures.

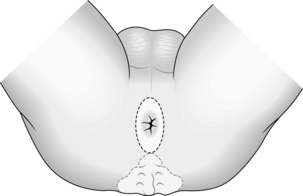

8. Close the anus with a strong non-absorbable purse-string suture such as 0 silk: encircle the anus twice before tying the purse-string to prevent faecal leakage.

ABDOMINAL OPERATION

Action

1. Suture the lower cut edge of the peritoneum and bladder to the skin.

2. Place the small bowel on the right side of the abdomen and cover it with a pack.

3. Divide the lateral attachments of the sigmoid and descending colon.

4. Lift the colon upwards and to the right, identify the left ureter and gonadal vessels and sweep them away from the vascular pedicle.

5. Enter the mesorectal plane and preserve the pelvic nerve plexus as described for anterior resection of the rectum. Divide the inferior mesorectal artery at its origin from the aorta, and the inferior mesenteric vein at the same level.

6. Select a suitable site in the sigmoid colon for transection of the bowel, taking into account the patient’s body habitus and the preoperative skin marking. If the colon easily reaches the symphysis pubis there should be sufficient length to allow construction of the stoma without tension and risk of subsequent retraction. Divide the mesocolon, ligating and dividing the marginal vessels to this point. Divide the colon using a Parker-Kerr clamp on the rectal side and non-crushing clamp on the colonic side or, ideally, divide the colon with a linear cutting stapler. This maintains sterility and the staple line can be excised from the colonic end when the wound is closed and the colostomy is constructed.

7. Construct a trephine in the left iliac fossa at the previously marked site for the colostomy. Remove a disc of skin 2 cm in diameter together with the underlying subcutaneous fat. Divide the rectus sheath, separating rather than cutting the underlying muscle fibres and incise the peritoneum.

8. Move to the patient’s left side and continue the mesorectal dissection posteriorly, laterally and anteriorly as for anterior resection of the rectum. Define the course of both ureters in the pelvis and be careful to preserve them. Continue the dissection as far as required, usually down to the pelvic floor and the tip of the coccyx posteriorly. For tumours adjacent to or involving the levator ani muscles a wider ‘extralevator’ abdominoperineal excision (ELAPE) will be required, and you should halt the abdominal dissection before the tumour is reached.

9. When the perineal dissection is completed withdraw the specimen through the perineal wound. Irrigate the pelvic cavity with aqueous 10% povidone-iodine solution.

10. Deliver the proximal colon through the trephine incision.

11. Ensure that you have achieved complete pelvic haemostasis.

12. It is not necessary to close the pelvic peritoneum. Attempts to approximate it under tension may result in subsequent dehiscence and herniation of the small bowel, resulting in a closed loop obstruction.

13. Close the abdominal wound.

14. Trim the staple line from the colostomy to leave 1 cm projecting above the skin. Suture the edge of the colon to the edge of the skin wound with interrupted polyglactin 910 sutures on a cutting needle.

PERINEAL OPERATION

In the male

1. Opinion is divided on the optimal positioning of the patient. Many surgeons advocate the prone jack-knife position, which gives superior views of the anterior dissection, particularly for wide ‘extralevator’ excision. If you select this option construct the colostomy, close the abdomen and turn the patient prone before commencing the perineal dissection.

2. Make an elliptical incision around the closed anus (Fig. 13.18) and deepen the incision to expose the fat of the ischiorectal fossae and the coccyx. Insert a Norfolk and Norwich self-retaining retractor.

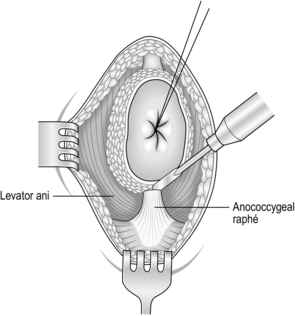

3. Begin the dissection posteriorly. Lift the anus forward, palpate the tip of the coccyx, and divide the anococcygeal raphe (Fig. 13.19). In extralevator excision the coccyx is excised: flex the coccyx to open the coccygeal joints and divide across it with a scalpel or reticulating bone saw to separate the distal portion. Coagulate any bleeding from the middle sacral vessels.

4. For small, mobile tumours the pelvic floor can be preserved by dissection in the intersphincteric plane, separating the levator muscles and puborectalis sling from the adjacent rectal fascia (see ‘Elective total proctocolectomy’ below). For extralavator excision extend the dissection outside the external sphincter, dividing the levator muscles laterally at their origin. Ligate or coagulate the inferior haemorrhoidal and pudendal vessels. If available, the Ligasure dissector is a great aid to bloodless dissection throughout the perineal operation.

5. Separate the mesorectum from the anterior aspect of the presacral fascia to enter the plane of the abdominal operation.

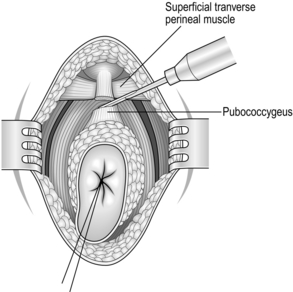

6. When the posterior and lateral dissection is complete, begin the anterior dissection. Retract the rectum posteriorly and make a transverse incision anteriorly to expose the superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles.

7. Divide the pubococcygeus and puborecto-urethralis muscles on either side of the rectum (Fig. 13.20). Then divide the underlying fascia, which is the lateral continuation of the fascia of Denonvilliers and Waldeyer, to expose the rectal wall. Palpate the prostate gland anteriorly and define the plane between the rectum and prostate.

8. Divide the fibres of the rectourethralis muscle to expose the prostatic capsule and dissect rostrally between the visceral pelvic fascia and the prostate and seminal vesicles until your dissection meets that of the abdominal operation.

9. Divide any remaining lateral attachments and draw the rectum and sigmoid colon through the perineal incision.

10. Flatten the operating table, irrigate the pelvis with warm isotonic saline and secure pelvic haemostasis using diathermy or 2/0 polyglactin 910 sutures. Place a suction drain into the pelvis through a stab wound anterolateral to the perineal wound (being careful to avoid the scrotum and the femoral vessels) and secure it to the skin.

11. Close the pelvic floor and subcutaneous tissue in two layers using interrupted 0 polyglactin 910 sutures. Close the skin with interrupted 3/0 Ethilon on a cutting needle.