Chapter 232 Coccidioidomycosis (Coccidioides Species)

Epidemiology

Infection results from inhalation of spores. Incidence increases during windy, dry periods that follow rainy seasons. Seismic events, archaeological excavations, and other activities that disturb contaminated sites have caused outbreaks. Person-to-person transmission does not occur. Rarely, infections result from spores that contaminate fomites or grow beneath casts or wound dressings of infected patients. Infection has also resulted from transplantation of organs from infected donors and from mother to fetus or newborn. Visitors to endemic areas can acquire infections, and diagnosis may be delayed when they are evaluated in nonendemic areas. Spores are highly virulent, and Coccidioides spp. are potential agents of bioterrorism (Chapter 704).

Clinical Manifestations

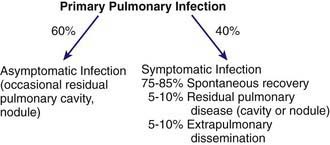

The clinical spectrum (Fig. 232-1) encompasses pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease. Pulmonary infection occurs in 95% of cases and can be divided into primary, complicated, and residual infections. About 60% of infections are asymptomatic. Symptoms in children are milder than those in adults. The incidence of extrapulmonary dissemination in children approaches that of adults.

Primary Coccidioidomycosis

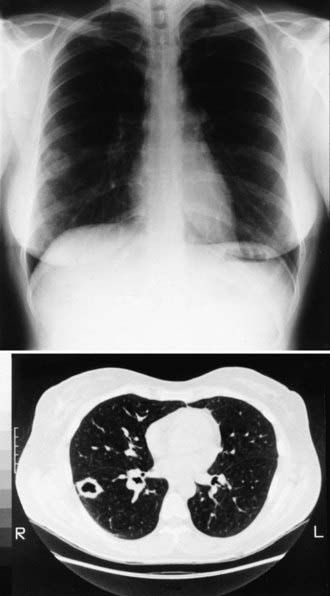

The incubation period is 1-4 wk, with an average of 10-16 days. Early symptoms include malaise, chills, fever, and night sweats. Chest discomfort occurs in 50-70% of patients and varies from mild tightness to severe pain. Headache and/or backache are sometimes reported. An evanescent, generalized, fine macular erythematous or urticarial eruption may be seen within the first few days of infection. Erythema nodosum can occur (more often in women) and is sometimes accompanied by an erythema multiforme rash, usually 3-21 days after the onset of symptoms. The clinical constellation of erythema nodosum, fever, chest pain, and arthralgias (especially knees and ankles) has been termed desert rheumatism and valley fever. The chest examination is often normal even if radiographic findings are present. Dullness to percussion, friction rub, or fine rales may be present. Pleural effusions can occur and can become large enough to compromise respiratory status. Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy are common (Fig. 232-2).

Dissseminated (Extrapulmonary) Infection

Clinically apparent dissemination occurs in 0.5% of patients. Its incidence is increased in infants; men; persons of Filipino, African, and Latin American ancestry; and in other Asians. Primary or acquired disorders of cellular immunity (Table 232-1) markedly increase the risk of dissemination.

Table 232-1 RISK FACTORS FOR POOR OUTCOME IN PATIENTS WITH ACTIVE COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

| PRIMARY INFECTIONS |

| Severe, prolonged (≥6 wk), or progressive infection |

| RISK FACTORS FOR EXTRAPULMONARY DISSEMINATION |

| Primary or acquired cellular immune dysfunction (including patients receiving tumor necrosis factor inhibitors) |

| Neonates, infants, the elderly |

| Male sex (adult) |

| Filipino, African, Native American, or Latin American ethnicity |

| Late-stage pregnancy and early postpartum period |

| Standardized complement fixation antibody titer >1:16 or increasing titer with persisting symptoms |

| Blood group B |

| HLA class II allele-DRBI*1301 |

Diagnosis

Culture, Histopathologic Findings, and Antigen Detection

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis should be performed in patients with suspected dissemination. The findings in meningitis are similar to those seen with tuberculous meningitis (Chapter 207). Eosinophilic pleocytosis may be present. Fungal stains and culture are usually negative. Volumes of 10 mL in adults have improved the yield of culture.

Imaging Procedures

During primary infection, chest radiography may be normal or demonstrate consolidation, single or multiple circumscribed lesions, or soft pulmonary densities. Hilar and subcarinal lymphadenopathy is often present (see Fig. 232-2). Cavities tend to be thin-walled (Fig. 232-3). Pleural effusions vary in size. The presence of miliary or reticulonodular lesions is prognostically unfavorable. Isolated or multiple osseous lesions are usually lytic and often affect cancellous bone. Lesions can affect adjacent structures, and vertebral lesions can impact the spinal cord.

Treatment

Based on the few rigorous clinical trials performed in adults and the opinions of experts in the management of coccidioidomycosis, consensus treatment guidelines have been developed (Table 232-2). Consultation with experts in an area of endemicity should be considered when formulating a plan of management.

Table 232-2 INDICATIONS FOR TREATMENT OF COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS IN ADULTS

| INDICATION | TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| Acute pneumonia, mild | Observe without antifungal treatment at 1-3 mo intervals for ≥1 yr; some experts recommend antifungal treatment |

| Weight loss >10%; sweats >3 wk; infiltrates at least half of one lung or parts of both lungs; prominent or persistent hilar lymphadenopathy; CF titers >1:16; inability to work, symptoms >2 mo | Treat with an azole daily for 3-6 mo, with follow up at 1-3 mo intervals for ≥1 yr |

| Uncomplicated acute pneumonia, special circumstances: immunosuppression, late pregnancy, Filipino or African ancestry, age >55 yr, other chronic diseases (diabetes, cardiopulmonary disease), symptoms >2 mo | Treat with an azole daily for 3-6 mo, with follow up at 1-3 mo intervals for ≥1 yr Treat with amphotericin B if in late pregnancy |

| Diffuse pneumonia: reticulonodular or miliary infiltrates suggest underlying immunodeficiency and possible fungemia, pain | Treat initially with amphotericin B if significant hypoxia or rapid deterioration, followed by an azole for ≥1 yr In mild cases, an azole for ≥1 yr |

| Chronic pneumonia | Treat with an azole for ≥1 yr |

| Disseminated disease, nonmeningeal | Treat with an azole for ≥1 yr except in severe or rapidly worsening cases for which amphotericin B is recommended |

| Disseminated disease, meningeal | Treat with fluconazole (some add intrathecal amphotericin B) and treat indefinitely |

CF, complement fixation.

Primary Pulmonary Infection

Patients with significant or prolonged symptoms are more likely to incur benefit from antifungal agents, but there are no established criteria upon which to base the decision. Commonly used indicators in adults are summarized in Table 232-2. A treatment trial in adults with primary respiratory infections examined outcomes of antifungal therapy prescribed on the basis of severity and compared them to an untreated group with less severe symptoms; complications occurred only in patients in the treatment group and only in those in whom treatment was stopped. If treatment is elected, a 3-6 mo course of fluconazole (6-12 mg/kg/day) or itraconazole (5-10 mg/kg/day) is recommended.

Diffuse Pneumonia

Diffuse reticulonodular densities or miliary infiltrates, sometimes accompanied by severe illness, can occur in dissemination or follow exposure to a large fungal inoculum. In this setting, amphotericin B is recommended for initial treatment followed thereafter by extended treatment with high-dose fluconazole (Table 232-2).

Disseminated Infection (Extrapulmonary)

For nonmeningeal infection (see Table 232-2), oral fluconazole and itraconazole are effective for treating disseminated coccidioidomycosis that is not extensive, is not progressing rapidly, and has not affected the CNS. Some experts recommend higher doses for adults than were used in clinical trials. A subgroup analysis showed a tendency for improved response of skeletal infections that were treated with itraconazole. Amphotericin B deoxycholate is used as an alternative, especially if there is rapid worsening and lesions are in critical locations. Voriconazole has been used successfully as salvage therapy. The optimal duration of therapy with the azoles has not been clearly defined. Late relapses have occurred after lengthy treatment and favorable clinical response.

Ampel NM. The complex immunology of human coccidioidomycosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1111:245-258.

Ampel NM, Giblin A, Mourani JP, et al. Factors and outcomes associated with the decision to treat primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Clin Inf Dis. 2009;48:172-178.

Blair J. Approach to the solid organ transplant patient with latent infection and disease caused by Coccidioides sp. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:415-420.

Blair JE. State-of-the-art treatment of coccidioidomycosis skeletal infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:422-433.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increase in coccidioidomycosis—California, 2000-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:105-108.

DiCaudo DJ, Yiannias JA, Laman SD, et al. The exanthem of acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:744-746.

Durkin M, Connolly P, Kuberski T, et al. Diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis with use of the Coccidioides antigen enzyme immunoassay. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:e69.

Fisher BT, Chiller TM, Prasad PA, et al. Hospitalizations for coccidioidomycosis at forty-one children’s hospitals in the United States. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:243-247.

Freifeld A, Proia L, Andes D, et al. Voriconazole use for endemic fungal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1648-1651.

Homans JD, Spencer L. Itraconazole treatment of nonmeningeal coccidioidomycosis in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:65-67.

Laniado-Laborin R. Expanding understanding of epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis in the western hemisphere. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:19-34.

Mathisen G, Shelub A, Truong J, et al. Coccidioidal meningitis. Medicine. 2010;89(5):251-284.

Saubolle MA. Laboratory aspects in the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:301-314.

Spinello IM, Munoz A, Johnson RH. Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:166-173.

Stevens DA, Rendon A, Gaona-Flores V, et al. Posaconazole therapy for chronic refractory coccidioidomycosis. Chest. 2007;132:952-958.

Williams PL. Coccidioidal meningitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:377-384.