chapter 1

Clinically Oriented Neuroanatomy

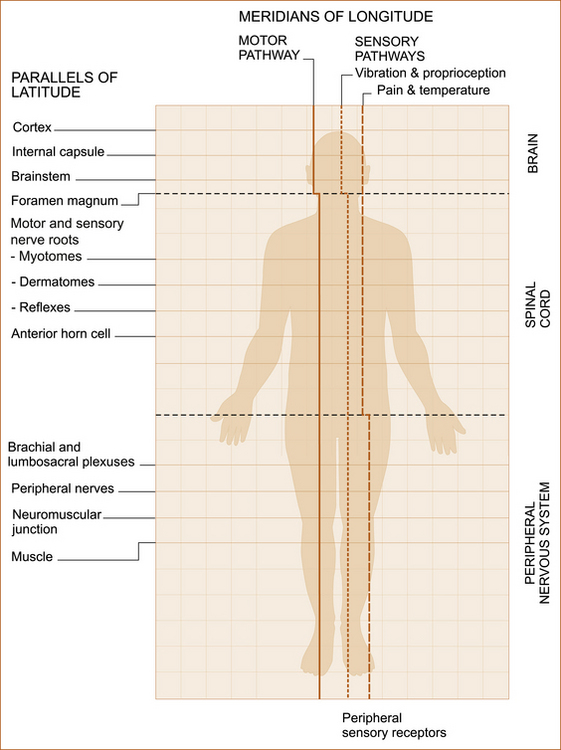

‘MERIDIANS OF LONGITUDE AND PARALLELS OF LATITUDE’

Although most textbooks on clinical neurology begin with a chapter on history taking, there is a very good reason for placing neuroanatomy as the initial chapter. It is because clinical neurologists use their detailed knowledge of neuroanatomy not only when examining a patient but also when obtaining a neurological history in order to determine the site of the problem within the nervous system. This chapter not only describes the neuroanatomy but attempts to place it in a clinical context.

The ‘student of neurology’ cannot be expected to remember all of the detail but needs to understand the basic concepts. This understanding, combined with the correct technique when taking the neurological history (see Chapter 2, ‘The neurological history’) and performing the neurological examination (see Chapter 3, ‘Neurological examination of the limbs’, Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’, and Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’), together with the illustrations in this chapter will enable the ‘non-neurologist’ to localise the site of the problem in most patients almost as well as the neurologist. It is intended that this chapter serve as a resource to be kept on the desk or next to the examination couch.

to disorders of the PNS, the anterior horn cell, motor nerve root, brachial or lumbrosacral plexus or peripheral nerve (see Table 1.1). The alterations in strength, tone, reflexes and plantar responses (scratching the lateral aspect of the sole of the foot to see which way the big toe points) are different in upper and lower motor neuron problems.

TABLE 1.1

Upper and lower motor neuron signs

| Upper motor neuron signs | Lower motor neuron signs | |

| Weakness | The UMN pattern∗ | Specific to a nerve or nerve root |

| Tone | Increased | Decreased |

| Reflexes | Increased | Decreased or absent |

| Plantar response | Up-going | Down-going |

∗The muscles that abduct the shoulder joint and extend the elbow and wrist joints are weak in the arms while the muscles that flex the hip and knee joints and the muscles that dorsiflex the ankle joint (bend the foot upwards) are weak in the legs.

The reason why this is so important is highlighted in Case 1.1.

CONCEPT OF THE MERIDIANS OF LONGITUDE AND PARALLELS OF LATITUDE

• The descending motor pathway from the cortex to the muscle

• The ascending sensory pathway for pain and temperature

• The ascending sensory pathway for vibration and proprioception

The ascending sensory pathways extend from the peripheral nerves to the cortex.1

The parallels of latitude

• Weakness + marked wasting – the peripheral nervous system, as marked wasting does not occur with central nervous system problems

• Weakness + cranial nerve involvement – brainstem

• Weakness + visual field disturbance (not diplopia) or speech disturbance (i.e. dysphasia) – cortex

• Weakness in both legs + loss of pain and temperature sensation on the torso – spinal cord

• Weakness in a limb + sensory loss in a single nerve (mononeuritis) or nerve root (radiculopathy) distribution – peripheral nervous system

THE MERIDIANS OF LONGITUDE: LOCALISING THE PROBLEM ACCORDING TO THE DESCENDING MOTOR AND ASCENDING SENSORY PATHWAYS

Cases 1.2 and 1.3 illustrate how to use the meridians of longitude.

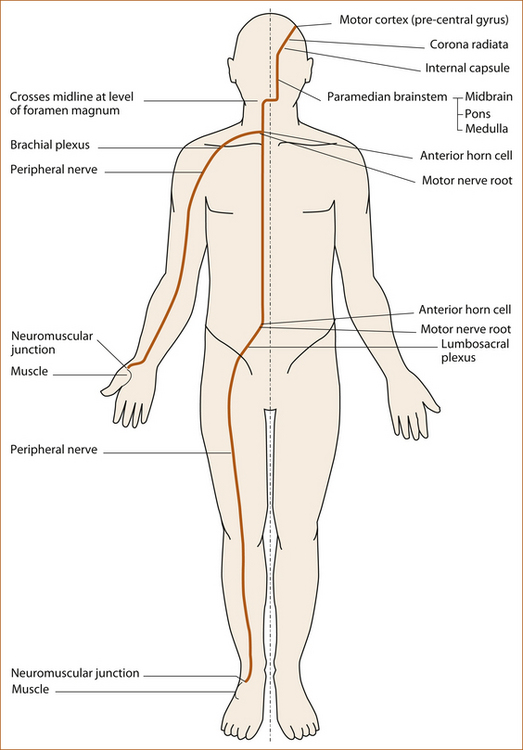

The motor pathway

The motor pathway (see Figure 1.2) refers to the corticospinal tract within the central nervous system that descends from the motor cortex to lower motor neurons in the ventral horn of the spinal cord and the corticobulbar tract that descends from the motor cortex to several cranial nerve nuclei in the pons and medulla that innervate muscles plus the motor nerve roots, plexuses, peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junction and muscle in the peripheral nervous system.

• arises in the motor cortex in the pre-central gyrus (see Figure 1.5) of the frontal lobe

• descends in the cerebral hemispheres through the corona radiata and internal capsule

• passes into the brainstem via the crus cerebri (level of midbrain) and descends in the ventral and medial aspect of the pons and medulla

• descends in the lateral column of the spinal cord to the anterior horn cell where it synapses with the lower motor neuron

• leaves the spinal cord through the anterior (motor) nerve root

• passes through the brachial plexus to the arm or through the lumbosacral plexus to the leg and via the peripheral nerves to the neuromuscular junction and muscle.

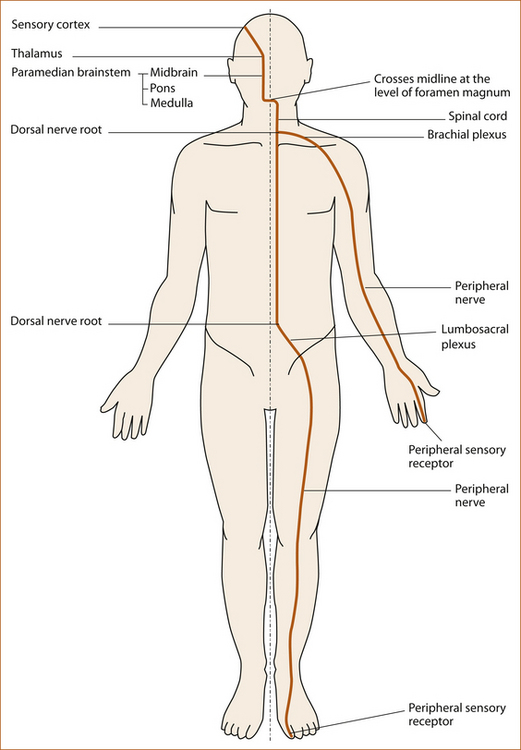

The sensory pathways

PROPRIOCEPTION AND VIBRATION

• arises in the peripheral sensory receptors in the joint capsules and surrounding ligaments and tendons (proprioception) or in the pacinian corpuscles in the subcutaneous tissue (vibration) [1]

• ascends up the limb in the peripheral nerves

• traverses the brachial or lumbosacral plexus

• enters the spinal cord through the dorsal (sensory) nerve root

• ascends in the ipsilateral dorsal column of the spinal cord with the sacral fibres most medially and the cervical fibres lateral

• ascends in the medial lemniscus in the medial aspect of the brainstem via the thalamus to the sensory cortex in the parietal lobe.

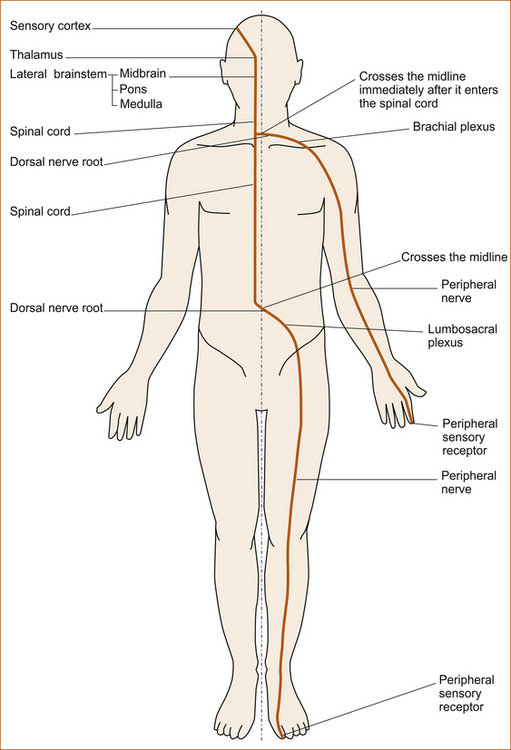

PAIN AND TEMPERATURE SENSATION

The spinothalamic pathway (see Figure 1.4):

FIGURE 1.4 The spinothalamic pathway

• includes the nerves conveying pain and temperature that arise in the peripheral sensory receptors in the skin and deeper structures [1]

• coalesces to form the peripheral nerves in the limbs or the nerve root nerves of the trunk

• from the limbs, traverses the brachial or lumbosacral plexus

• enters the spinal cord through the dorsal (sensory) nerve root

• ascends in the spinothalamic tract located in the anterolateral aspect of the spinal cord, with nerves from higher in the body pushing those from lower laterally in the spinal cord

• ascends in the lateral aspect of the brainstem to the thalamus.

Case 1.4 illustrates a patient with both motor and sensory pathways affected.

THE PARALLELS OF LATITUDE: FINDING THE SITE OF PATHOLOGY WITHIN THE STRUCTURES OF THE CENTRAL AND PERIPHERAL NERVOUS SYSTEMS

In the CNS the parallels of latitude consist of:

• the cortex – vision, memory, personality, speech and specific cortical sensory and visual phenomena such as visual and sensory inattention, graphaesthesia (see Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’)

• the cranial nerves of the brainstem (see Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’) – each cranial nerve is at a different level in the brainstem and thus represents a parallel of latitude. For example, if the patient has a 7th nerve palsy the problem either has to be in the 7th nerve or in the brainstem at the level of the pons.

The nerve roots and peripheral nerves are the parallels of latitude in the PNS:

• The motor and sensory nerves when affected will result in a very focal pattern of weakness and/or sensory loss that clearly indicates that the problem is in the peripheral nerve (see Chapter 11, ‘Common neck, arm and upper back problems’ and Chapter 12, ‘Back pain and common leg problems with or without difficulty walking’).

• myotomes – motor nerve roots supplying muscles produce a classic pattern of weakness of several muscles supplied by that nerve root; specific nerve roots are part of the reflex arc and if, for example, the patient has an absent biceps reflex the lesion is at the level of C5–6

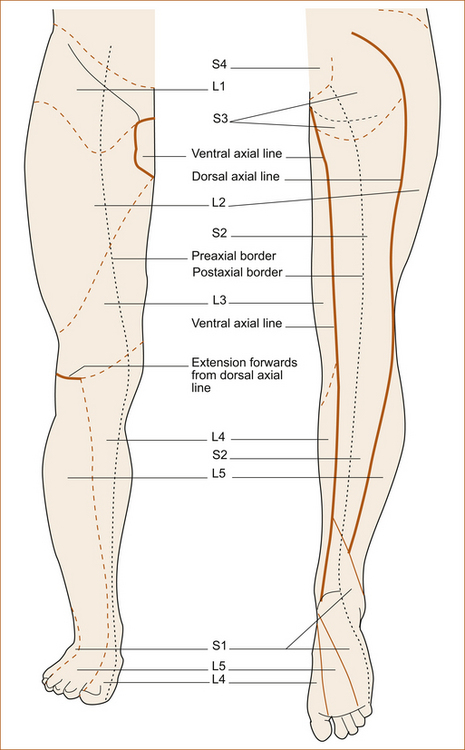

• dermatomes – areas of abnormal sensation from involvement of sensory nerve roots (see Figures 1.12, 1.13 and 1.22).

Parallels of latitude in the central nervous system

If a patient has a problem within the CNS, involvement of either the cortex or the brainstem will produce symptoms and signs that will enable accurate localisation. For example, the patient who presents with weakness involving the right face, arm and leg clearly has a problem affecting the motor pathway (the meridian of longitude) on the left side of the brain above the mid pons. The presence of a left 3rd nerve palsy (the parallel of latitude) would indicate the lesion is on the left side of the mid-brain while the presence of a non-fluent dysphasia (another parallel of latitude) would localise the problem to the left frontal cortex. Case 1.5 illustrates how to use the parallels of latitude in the CNS.

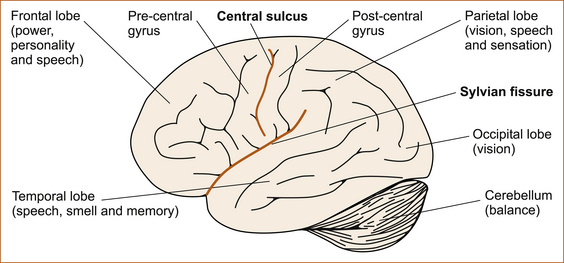

THE HEMISPHERES

Figure 1.5 is a simplified diagram showing the main lobes of the brain and the cortical function associated with those areas. If the patient has cortical hemisphere symptoms and signs this clearly establishes the site of the pathology in the cortex of a particular region of the brain.

THE BRAINSTEM

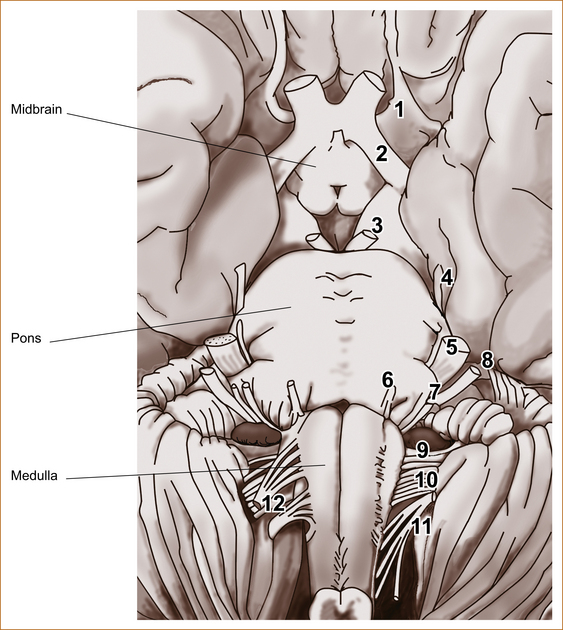

Figure 1.6 shows the site of the cranial nerves in the brainstem with the numbers added: the 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th cranial nerves at the level of the medulla; the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th at the level of the pons; and the 3rd and 4th at the level of the midbrain (see Chapter 4 for a detailed discussion of the brainstem and cranial nerves). Also note that the 3rd, 6th and 12th cranial nerves exit the brainstem close to the midline while the other cranial nerves exit the lateral aspect of the brainstem.

FIGURE 1.6 The ventral aspect of the brainstem showing the cranial nerves Reproduced and modified from Gray’s Anatomy, 37th edn, edited by PL Williams et al, 1989, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 7.81 [2]

Parallels of latitude in the peripheral nervous system

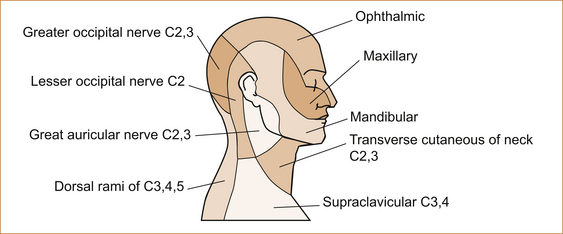

In Figure 1.7 the important points to note are:

FIGURE 1.7 Dermatomes and nerves of the head and neck Reproduced from Gray’s Anatomy, 37th edn, edited by PL Williams et al, 1989, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 7.242 [2]

• The 1st division of the trigeminal nerve extends over the scalp to somewhere between the vertex and two-thirds of the way back towards the occipital region where it meets the greater occipital nerve supplied by the 2nd cervical nerve root. In a trigeminal nerve lesion the sensory loss will not extend to the occipital region, whereas with a spinothalamic tract problem it will.

• The 2nd and 3rd (predominantly the 3rd) cervical sensory nerve root supplies the angle of the jaw helping to differentiate trigeminal nerve sensory loss from involvement of the spinothalamic/quintothalamic tract. The angle of the jaw and neck are affected with lesions of the quinto/spinothalamic tract. Sensory loss on the face without affecting the angle of the jaw indicates the lesion is involving the 5th cranial nerve.

• The upper lip is supplied by the 2nd division and the lower lip by the 3rd division of the trigeminal nerve.

The corneal reflex afferent arc is the 1st division of the trigeminal nerve; the nasal tickle reflex is the 2nd division (see Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’).

The anatomies of the muscles to the eye, the visual pathway and the vestibular pathway are discussed in Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’.

The purpose of the illustrations in the remainder of this chapter is to serve as a reference point for future use, and it is not anticipated that the reader will remember them all. With this textbook at the bedside the clinician can quickly refer to the illustrations to work out the anatomical basis of the pattern of weakness or of sensory loss.

THE UPPER LIMBS

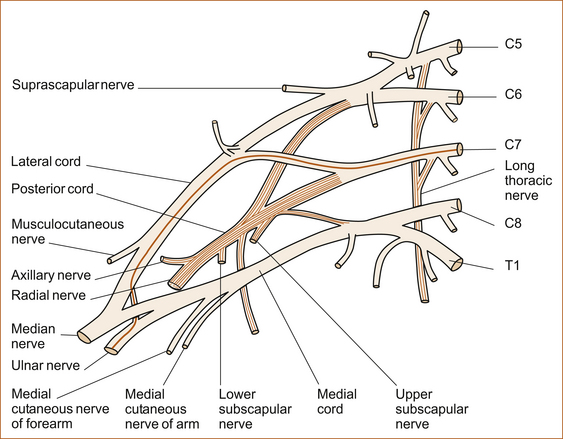

Brachial plexus: The most important aspects to note in Figure 1.8 are:

FIGURE 1.8 Brachial plexus Reproduced and modified from Gray’s Anatomy, 37th edn, edited by PL Williams et al, 1989, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 7.243 [2]

• The suprascapular nerve and the long thoracic nerve arise from the nerve roots (C5, C6 and C7) proximal to the junction of C5 and C6, helping to differentiate between a brachial plexus lesion at the level of C5–C6 and a nerve root lesion.

• The radial nerve arises from C5, C6 and C7.

• The median nerve arises from C5, C6, C7, C8 and T1.

• The ulnar nerve arises from the 8th cervical and 1st thoracic nerve roots. The clinical features of ulnar nerve lesions and pathology affecting the C8–T1 nerve roots are very similar, and a detailed examination is usually required to differentiate between these two entities.

Motor nerves and muscles of the upper limb:

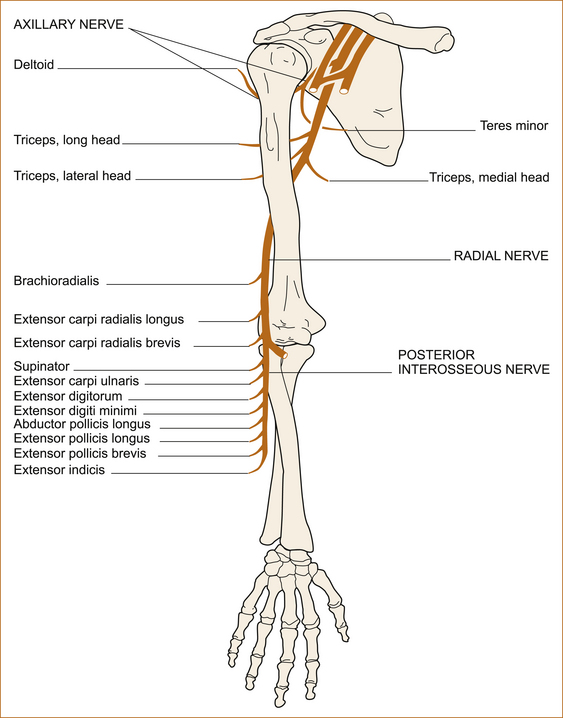

AXILLARY AND RADIAL NERVES: Figure 1.9 shows the muscles innervated by the axillary and radial nerves. The important points to note are:

FIGURE 1.9 The axillary nerve and radial nerves Reproduced from Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System, 4th edn, Brain, 2000, Saunders, Figure 15, p 12 [3]

• The axillary only supplies the deltoid muscle, not the other muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus and subscapularis) around the shoulder that collectively form the rotator cuff. Weakness isolated to the deltoid will indicate an axillary nerve lesion (occasionally seen with a dislocated shoulder).

• The branches of the radial nerve to the triceps muscle arise from above the spiral groove of the humerus. The spiral groove is a common site for compression and thus the triceps is not affected.

• The branches to the brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus and extensor carpi radialis brevis arise proximal to the posterior interosseous nerve, these will be affected by a radial nerve palsy but spared if the problem is confined to the posterior interosseous nerve.

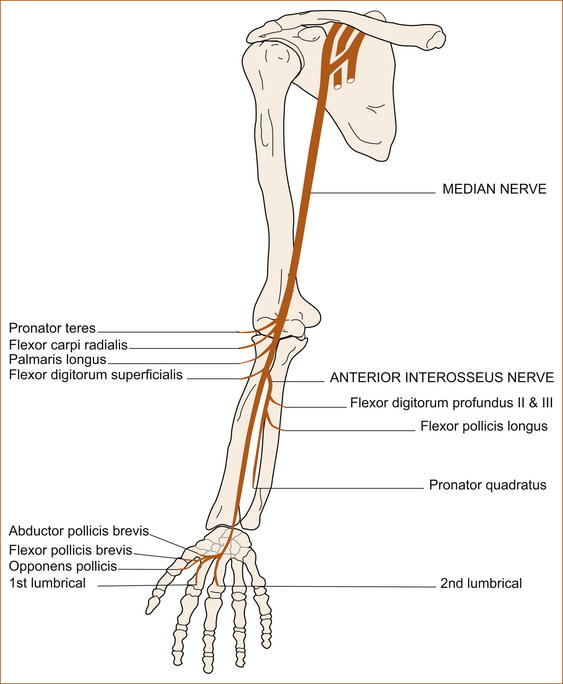

MEDIAN NERVE: Figure 1.10 shows the muscles supplied by the median nerve. The points to note are:

FIGURE 1.10 The median nerve Reproduced from Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System, 4th edn, Brain, 2000, Saunders, Figure 27, p 20 [3]

• The branches to the flexor carpi radialis (flexes the wrist) and flexor digitorum superficialis (flexes the medial four fingers at the proximal interphalangeal joint) arise near the elbow, proximal to the anterior interosseous nerve.

• The anterior interosseous nerve supplies the flexor pollicis longus (flexes the distal phalanx of the thumb), the pronator quadratus (turns the wrist over so that the palm is facing downwards) and the lateral aspect of the flexor digitorum profundus (flexes the distal phalanges of the 2nd and 3rd digits).

• The nerve to abductor pollicis brevis, the muscle that elevates the thumb when the hand is fully supinated (palm facing the ceiling), arises at or just distal to the wrist in the region of the carpal tunnel.

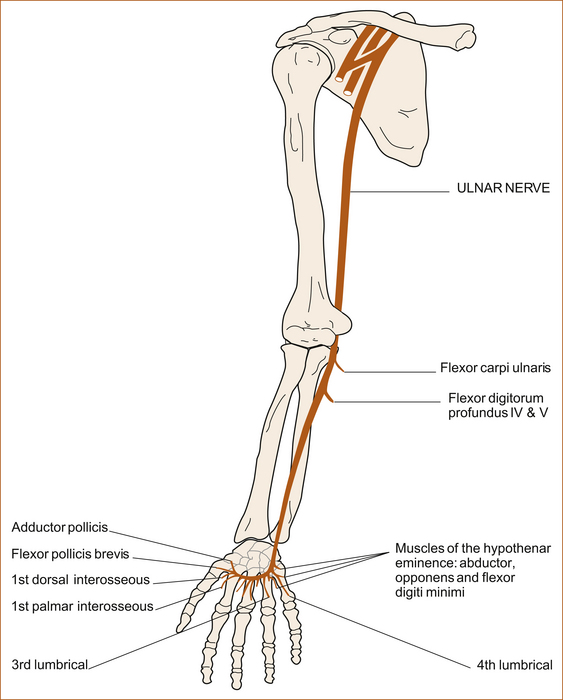

ULNAR NERVE: Figure 1.11 shows the muscles innervated by the ulnar nerve. The points to note are:

FIGURE 1.11 The ulnar nerve Reproduced from Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System, 4th edn, Brain, 2000, Saunders, Figure 36, p 26 [3]

• The branches to the flexor carpi ulnaris (flexes the wrist) and medial aspect of the flexor digitorum profundus (flexes the distal phalanges of the 4th and 5th digits) arise just distal to the medial epicondyle and will be affected by lesions at the elbow, a common sight of compression of the ulnar nerve. The lateral aspect of flexor digitorum profundus is innervated by the median nerve and, thus, flexion of the 2nd and 3rd distal phalanges will be normal with an ulnar nerve lesion at the elbow while they will be affected by C8–T1 nerve root or lower cord brachial plexus lesions.

Case 1.6 illustrates a problem with the ulnar nerve.

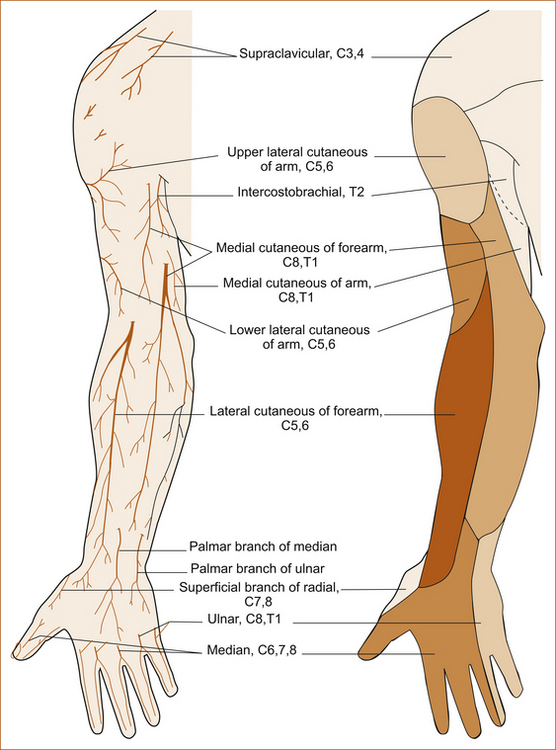

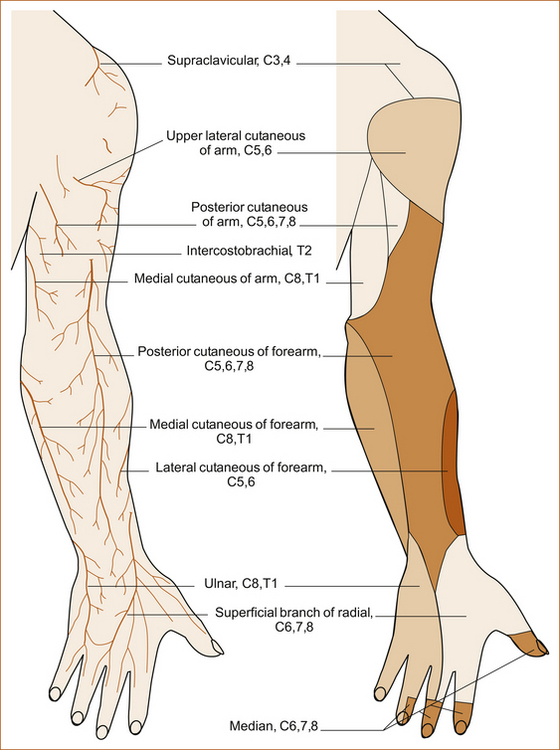

Cutaneous sensation of the upper limbs and trunk: Below each illustration are the one or two important features that are most useful at the bedside.

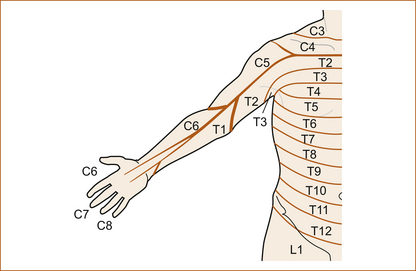

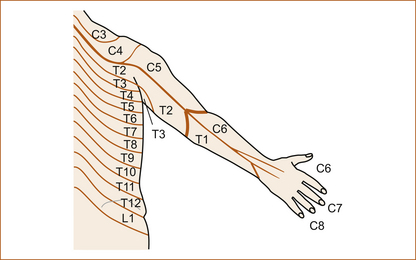

The areas of sensation in the upper limb and trunk supplied by the sensory nerve roots, the dermatomes, are shown in Figures 1.12 and 1.13. A simple method of remembering the dermatomes is:

FIGURE 1.12 Dermatomes of the trunk and upper limb (anterior aspect) Reproduced from Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System, 4th edn, Brain, 2000, Saunders, Figure 87, p 56 [3]

FIGURE 1.13 Dermatomes of the trunk and upper limb (posterior aspect) Reproduced from Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System, 4th edn, Brain, 2000, Saunders, Figure 88, p 57) [3]

FIGURE 1.14 Sensory nerves of the upper limbs (anterior aspect) Reproduced from Gray’s Anatomy, 37th edn, edited by PL Williams et al, 1989, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 7.244 [2]

FIGURE 1.15 Sensory nerves of the upper limbs (posterior aspect) Reproduced from Gray’s Anatomy, 37th edn, edited by PL Williams et al, 1989, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 7.245) [2]

• The arm–C7 affects the 3rd finger, C6 is lateral to this and C8 is medial to this.

• The trunk–T2 is at the level of the clavicle and meets C4; T8 is at the level of the xiphisternum (the lower end of the sternum), T10 is at the level of the umbilicus and T12 is at the level of the groin.

Figure 1.13 shows why it is very important to roll the patient over or sit them up to examine any sensory loss on the trunk. The dermatomes are higher on the back than they are on the front of the trunk. Sensory loss that is at the same horizontal level on both the anterior and posterior aspects of the trunk is not related to organic pathology and is more likely to be of functional origin.

THE LOWER LIMBS

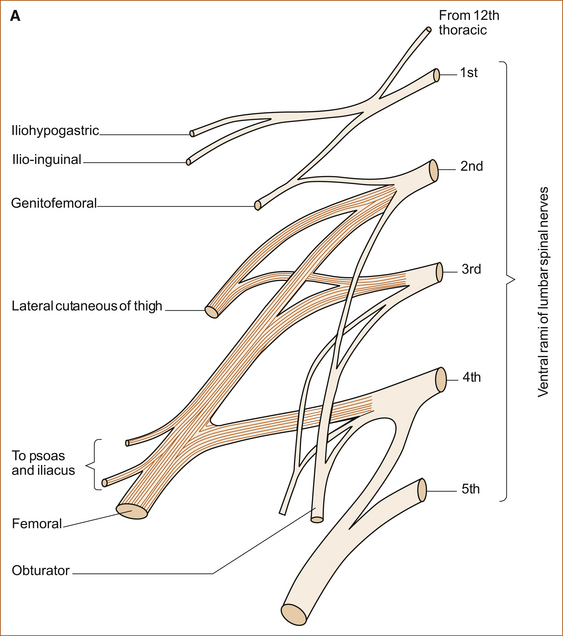

Lumbar and sacral plexuses: Unlike the brachial plexus, there is little in the lumbosacral plexus (Figure 1.16) that helps localise whether the problem is in the lumbosacral plexus or the nerve roots. It is important to note that the sciatic nerve arises from predominantly the 5th lumbrical at the 1st and 2nd sacral nerve roots.

The motor nerves and muscles of the lower limb:

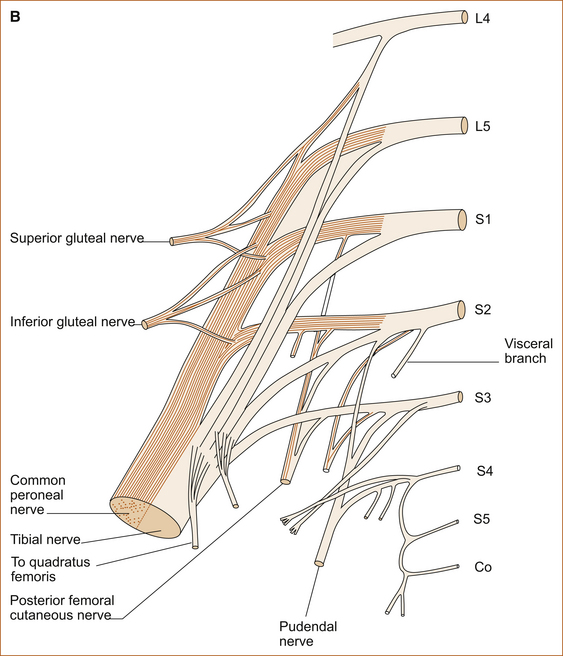

FEMORAL NERVE: The point to note (see Figure 1.17) is that the common peroneal nerve arises from the sciatic nerve above the popliteal fossa and above the level of the neck of the fibula, a common site for compression, and that there are no branches between where it arises and the neck of the fibula.

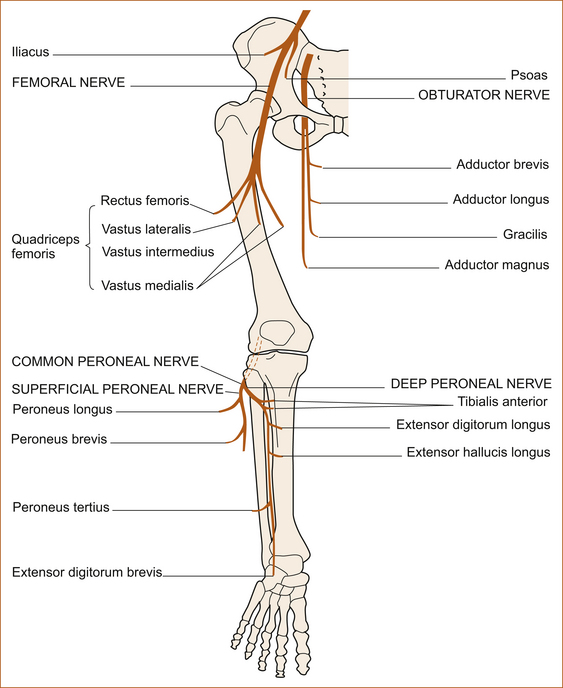

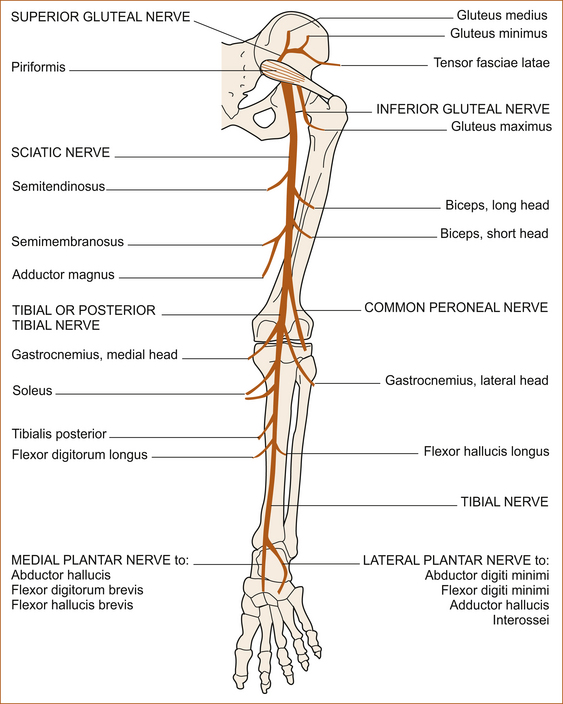

SCIATIC NERVE: The point to note is that the tibialis posterior muscle is supplied by the posterior tibial nerve while the tibialis anterior muscle is supplied by the common peroneal nerve (see Figure 1.18). Examining these muscles individually in patients with a foot drop helps to differentiate between a common peroneal nerve palsy and an L5 nerve root lesion. Inversion is stronger in a common peroneal nerve lesion while eversion is stronger with an L5 nerve root lesion. (See Chapter 12, ‘Back pain and common leg problems with or without difficulty walking’.)

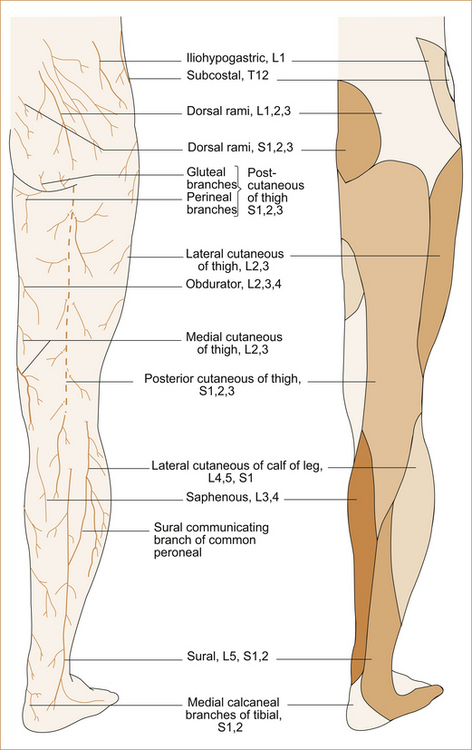

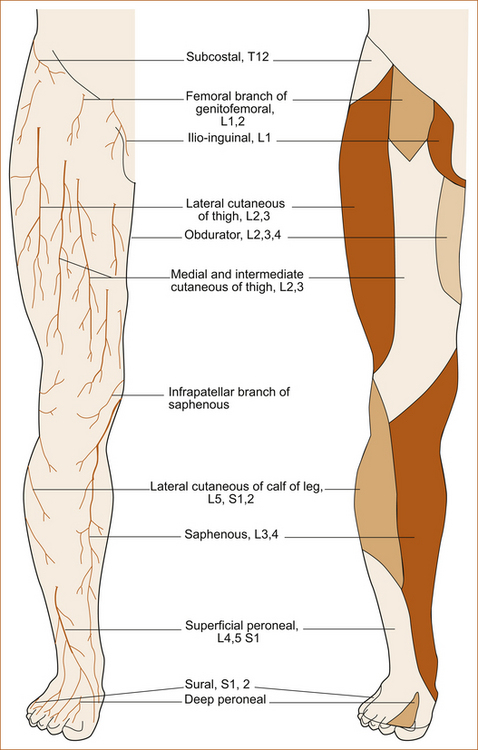

Cutaneous sensation of the lower limbs: As discussed with reference to the upper limbs and trunk, Figures 1.19–1.22 are supplied as a reference source along with some important clinical clues.

FIGURE 1.19 The sensory nerves of the lower limbs (posterior aspect) Reproduced from Gray’s Anatomy, 37th edn, edited by PL Williams et al, 1989, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 7.258) [2]

FIGURE 1.20 The sensory nerves of lower limbs (anterior aspect) Reproduced from Gray’s Anatomy, 37th edn, edited by PL Williams et al, 1989, Churchill Livingstone, Figure 7.254 [2]

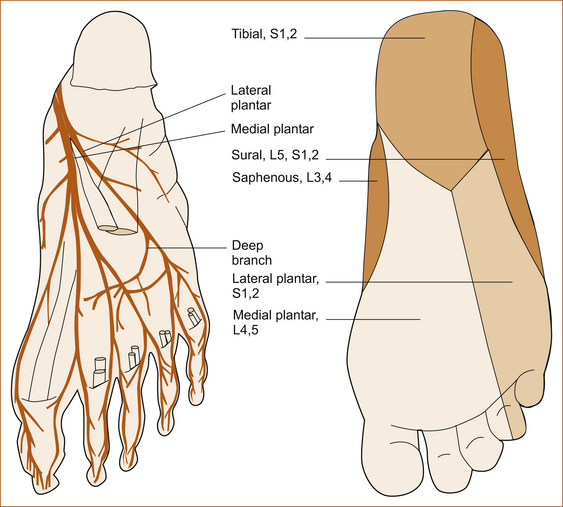

FIGURE 1.21 The sensory nerves affecting the soles of the feet Reproduced from Gray’s Anatomy, 37th edn, edited by PL Williams et al, 1989, Churchill Livingstone, Figure X, p Y [2]

USEFUL LANDMARKS FOR REMEMBERING CUTANEOUS SENSATION: Rather than trying to remember all the dermatomes, the following landmarks can be used.

• T12 is at the level of the groin (see Figure 1.12).

• L3 crosses the knee (see Figure 1.22).