Clinical examination of the thoracic spine

Introduction

Principal differences between the thoracic and the lumbar and cervical spines

Visceral versus musculoskeletal pain

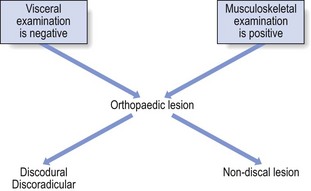

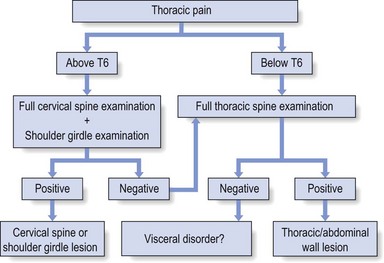

The best method of differentiating is to work in two complementary ways: exclusion of any visceral disorder through a thorough internal check-up, together with positive confirmation of a provisional orthopaedic diagnosis (Fig. 25.1). This routine will also safeguard against unnecessary technical investigations and delays in diagnosis and treatment.1–3

Discal lesions

Discodural and discoradicular interactions are well-known causes of cervical and lumbar pain.

In a discodural lesion, a shifted component of the disc impinges on the dura and causes pain that has multisegmental characteristics (crossing the midline and occupying several dermatomes). Discodural conflicts are characterized by two sets of symptoms and signs: articular and dural (see Ch. 33).

• The articular signs are subtle: a discodural interaction at the cervical or lumbar level usually presents with a clear partial articular pattern: some movements hurt or are limited and others do not, always in an asymmetrical way. This is not so in the thoracic spine. Because of the rigidity of the thorax, such an obvious pattern is seldom found. Very often, only one of the six passive movements, usually a rotation, is positive and then only slightly so. Therefore diagnosis in the thoracic spine is more tentative and may have to be based on smaller, subtler abnormalities.

• Neurological deficit is seldom encountered in a thoracic disc lesion: whereas some degree of neurological deficit is a common finding in cervical or lumbar posterolateral disc lesions, muscular weakness is rarely detectable in thoracic discoradicular lesions. Also, disturbance of sensation is very rare. This absence of neurological signs is probably the outcome of the location of the nerve root in the intervertebral foramen, where it lies mainly behind the lower aspect of the vertebral body and less behind the disc (see online chapter Applied anatomy of the thorax and abdomen).

• There is no tendency to spontaneous recovery: in the lumbar and cervical spines there is usually a spontaneous cure for root pain, which seldom lasts longer than 4 months at the cervical level and 12 months at the lumbar level. At the thoracic level, no such tendency exists and constant root pain can persist for many years.

• Protrusions can usually be reduced: although thoracic disc lesions are more difficult to diagnose, they are easily and effectively cured. Protrusions – no matter how long they have been present, or whether they are posterocentral or posterolateral, or soft or hard – can usually be reduced by 1–3 sessions of manipulations. Unlike at the lumbar or cervical levels, time is not a criterion for reducibility. Hence a disc displacement may well prove reducible after constant root pain, even of several years’ standing. Traction is seldom required because the protrusions are usually of the annular type.

Referred pain

Pain referred from musculoskeletal structures

Dura mater and nerve roots

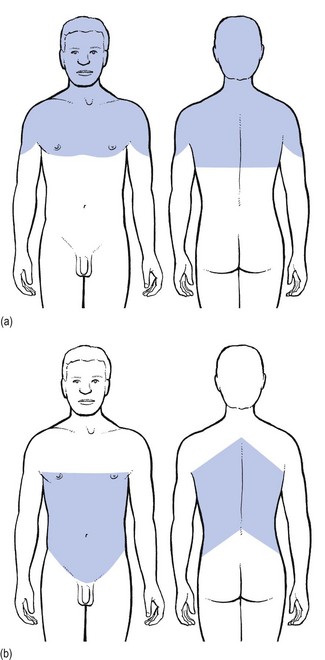

Pain originating from the dura mater is referred in a multisegmental way: it crosses the midline and may cover several consecutive dermatomes (see p. 18). A possible explanation for this phenomenon may lie in its multisegmental origin, which is reflected in the considerable overlap between the fibres of the consecutive sinuvertebral nerves innervating its anterior aspect.4 Recent research has demonstrated that dural pain may spread over eight segments with considerable overlap between adjacent and contralateral dura mater.5 This may be an explanation for the fact that lower cervical discodural conflicts may produce pain that spreads into the upper thoracic level (Fig. 25.2a) or that lumbar dural pain causes pain in the lower thoracic region (Fig. 25.2b).

Cervical disc lesions

Some cervical disc lesions may cause pain in the thoracic region.

Cervical discodural interactions

Low cervical discodural interactions very often result in unilateral interscapular pain, usually felt above T6 and spread over several dermatomes. The pain is also often referred to the sternum and the precordial region. Exceptionally, the pain may be felt only in the anterior chest, so misleading almost all clinicians. It is important to remember that extrasegmentally referred pain of cervical origin never spreads into the upper limb (see p. 18).

Cervical discoradicular interactions

A posterolateral disc protrusion compressing the C5, C6, C7 or C8 nerve root gives rise to unilateral root pain characterized mainly by a sharp pain down the upper limb. There may also be some degree of scapular pain, especially in C7 lesions, but this is usually not very severe (see p. 156).

Thoracic disc lesions

Thoracic discodural interactions

It is important to note that extrasegmental pain from a posterocentral thoracic disc protrusion usually remains in the trunk itself, where it can spread anteriorly and/or posteriorly over several segments (see Fig. 25.2b). It seldom spreads into the neck or into the buttocks. The pain is usually unilateral and spreads over several segments. Exceptionally it is felt centrally at the spine, radiating bilaterally towards the sides.

Thoracic discoradicular interactions

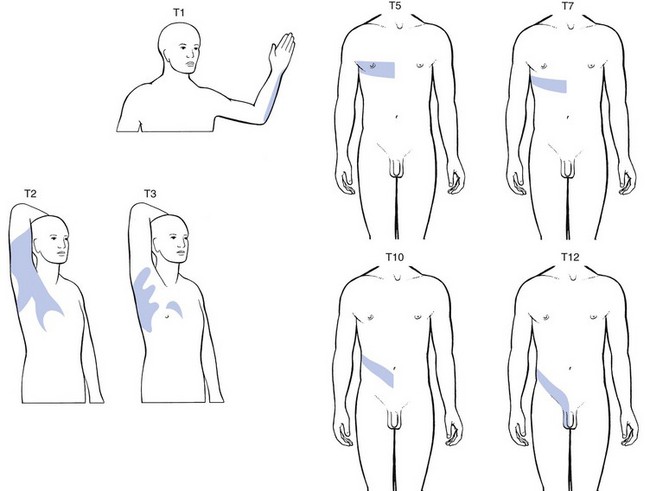

A posterolateral impingement on the two upper thoracic roots produces pain felt in the arm (Fig. 25.3). If the T1 nerve root is involved, pain may be referred to the ulnar side of the forearm, whereas a T2 nerve root compression gives rise to pain felt over the inner aspect of the arm from the elbow to the axilla, at the anterior aspect of the upper thorax around the clavicle and at the posterior upper thorax around the scapular spine. Clinically the upper two thoracic segments belong to the cervical spine and are thus most easily examined with the cervical segments.

If the 3rd–12th root is compressed, pain spreads unilaterally as a band around the thorax, sometimes reaching anteriorly as far as the sternum (see Fig. 25.3).

The following landmarks may be helpful in determining which root is involved:

• If pain is felt around the nipple, the T5 nerve root is at fault.

• Because the epigastrium belongs to the T7 and T8 segments, pain present here arises from structures of the same origin.

• Pain at the umbilicus and in the iliac fossa may point to a lesion of the T9, T10 and T11 nerve roots.

• If the T11 or T12 thoracic root is compressed, pain may be referred to the groin or even further down to the testicle.

Bones

• Traumatic fracture of a vertebral body: severe central pain is to be expected for about 2–6 weeks. For the first week there is often girdle pain. Thereafter it gradually disappears. If uncomplicated, spontaneous cure is to be expected within 12 weeks.

• Vertebral tumours: all types of bony tumour of the vertebrae, primary or metastatic, as well as infections, initially provoke local pain in the centre of the back.

• Contusion or fracture of a rib: the patient can point exactly to the tender spot. The same is the case in malignant invasion.

• Disorders of the sternum: traumatic disorders and tumours of the sternum may also give rise to local sternal pain.

Joints and ligaments

• Manubriosternal and sternoclavicular joints: as these are superficially located, the pain is felt locally.

• Costochondral and chondrosternal joints (Tietze’s syndrome and costochondritis): the patient is able to indicate the site of the lesion accurately.

• Intervertebral facet joints: these give rise to unilateral paravertebral pain, felt deeply and locally, but not going further lateral than the medial edge of the scapula. If several joints are affected at the same time, as may be the case in ankylosing spondylitis, the pain spreads more in a craniocaudal direction than mediolaterally; the opposite is true for a disc protrusion.

• Costovertebral and costotransverse joints: the pain is felt unilaterally between the vertebral column and the scapula.

• Anterior longitudinal ligament: when this ligament is affected, pain is usually located anteriorly behind the sternum.

• Posterior longitudinal ligament: involvement of this ligament causes pain in the back, felt centrally between the scapulae.

• Disorders of the costocoracoid fascia or the trapezoid and conoid ligaments (see online chapter Disorders of the inert structures): the pain is usually felt in the infraclavicular fossa.

Pain referred from visceral structures

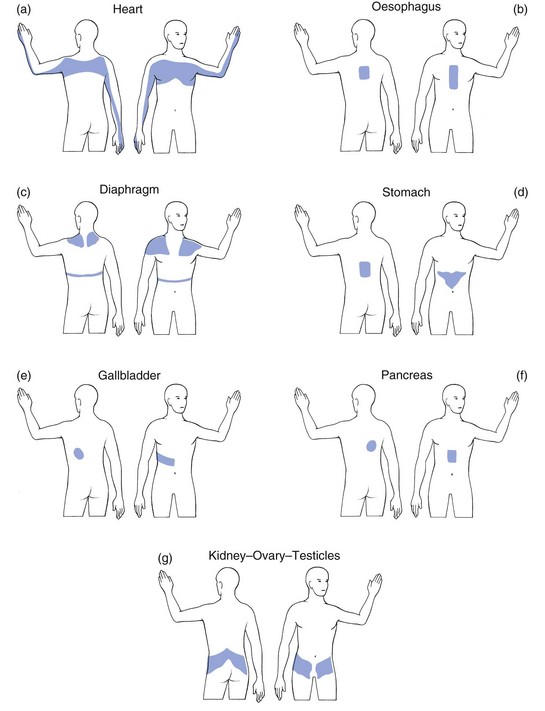

The heart

Pain arising from disorders of the heart can be referred to dermatomes C8–T4 because the heart is derived largely from these segments. Therefore pain can radiate towards the tip of the shoulder, to the anterior chest and to the corresponding region of the back. It may also be referred towards the ulnar side of both upper limbs, though referral to the left side is more common (Fig. 25.4a). Pain from the pericardium always arises from the parietal surface because this is the only part which has a sensory innervation.

The lungs

The parietal pleura

Pleuritic pain is caused by an inflammation of the parietal pleura (pleurisy). Though the visceral pleura does not contain any nociceptors, the parietal pleura is innervated by somatic nerves that sense pain when the parietal pleura is inflamed. Parietal pleurae of the outer rib cage and lateral aspect of each hemidiaphragm are innervated by intercostal nerves. Pain is localized to the cutaneous distribution of those nerves. The phrenic nerve supplies innervations to the central part of each hemidiaphragm which is a C4 structure, with pain reference to the trapezius area.6

The oesophagus

Disorders of the oesophagus (T4–T6) usually give rise to pain felt at any part of the sternum, often radiating between the scapulae into the back (Fig. 25.4b).

The diaphragm

The central part of the diaphragm is mainly derived from the third, fourth and sometimes, although rarely, the fifth cervical segments. Pain from irritation of the central part of the diaphragm is felt at the tip of the shoulders and the base of the neck. Pain from the peripheral part is felt more locally in the lower thorax and in the upper abdomen at the costal margin (Fig. 25.4c).

The stomach and duodenum

Pain from stomach and duodenum (T6–T10) is most commonly felt in the epigastrium and upper abdomen, sometimes substernally and exceptionally in the lower thoracic part of the back (Fig. 25.4d).

The liver, gallbladder and bile ducts

The liver is derived from the right side of T7–T9. The gallbladder and bile ducts are of right T6–T10 origin. Pain is felt in the right hypochondrium and may radiate towards the inferior angle of the right scapula (T7–T9) (Fig. 25.4e).

The pancreas

Patients suffering from a pancreatic disorder complain of upper abdominal pain often referred to the back at T8 (Fig. 25.4f).

The kidneys and ureters

Disorders of kidney and ureters (T10–L1) give rise to pain felt posteriorly in the side, at and just below the lower ribs, and at the anterolateral aspect of the abdomen. The pain often radiates towards the testicles or the labia (Fig. 25.4g).7

History

Pain

Functional examination

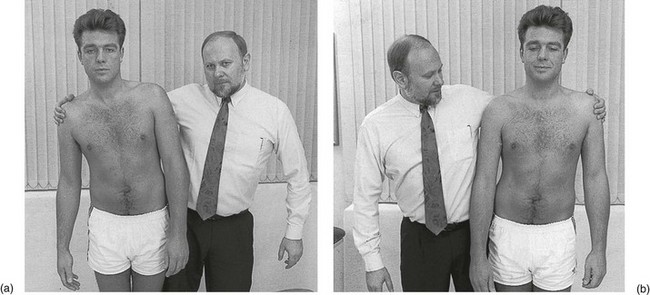

Clinical routine differs significantly according to the level of the pain (Fig. 25.5). For a number of reasons, pain felt above the T6 level (mid-scapular) demands a preceding clinical examination of the cervical spine and the shoulder girdle. First, the upper two thoracic vertebrae, anatomically belonging to the thoracic spine but clinically part of the cervical spine, are tested in the clinical examination of the cervical spine. Second, it was demonstrated previously that cervical discodural interactions often provoke extrasegmentally referred pain in the upper half of the thorax. Third, numerous lesions of the thoracic apex and the shoulder girdle, although causing pain in the cranial aspect of the thorax, are only detected by proper examination of the cervical spine and/or the shoulder girdle: a tumour of the apex of the lung involving the T1 nerve root is only detected by cervical tests; neuritis of the suprascapular nerve causes pain in the supraspinatus fossa and is detected by a combined weakness of supra- and infraspinatus muscles. A fracture of the first rib provokes upper thoracic pain but the diagnosis can be missed if the examiner proceeds immediately with examination of the thoracic spine. For all these reasons, in patients with upper thoracic pain, a full cervical examination followed by examination of the shoulder girdle must be done first. Only when these are negative should a thorough examination of the thoracic spine follow.

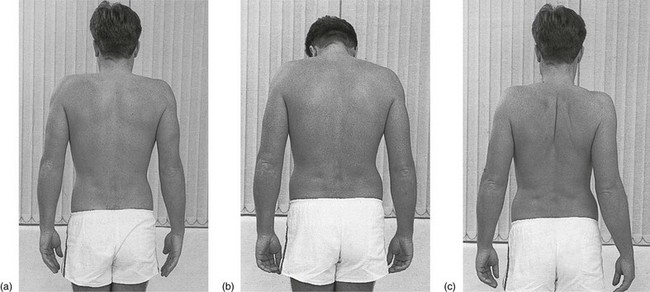

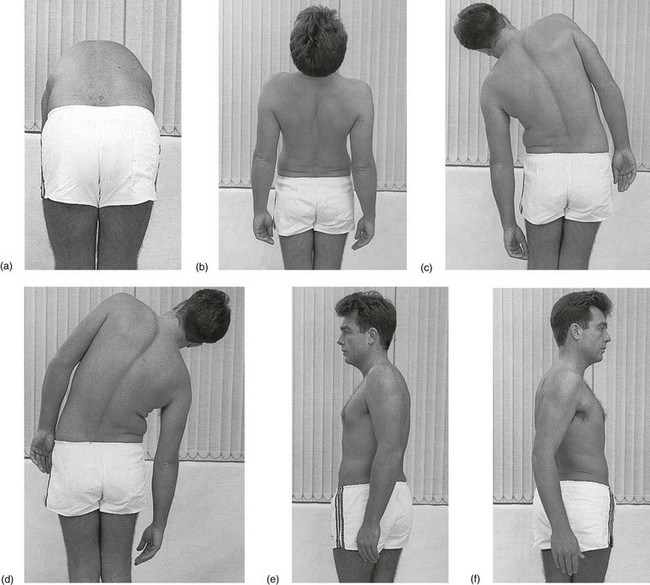

Standing

Dural tests

Flexion of the neck (Fig. 25.6b)

Sometimes a patient feels a sudden sensation on neck flexion, resembling an electrical discharge going down his back and occasionally even spreading towards both arms and legs. Sometimes it also occurs on extension of the neck. This is known as Lhermitte’s sign and was previously regarded as pathognomonic for disorders of the cord at the cervical level. In later reports it has been suggested that problems of the thoracic cord may cause the same sign. This can be caused by multiple sclerosis, a tumour of the cord, disc lesions, tuberculosis, spondylosis, arachnoiditis or radiation myelopathy.8

Shoulder movements: upwards, forwards and backwards

The patient is now asked to shrug both shoulders and to bring them forwards and backwards.

These tests are basically active movements of the structures of the shoulder girdle. Therefore some will be positive when a disorder of one of those structures is present (see online chapter Applied anatomy of the shoulder girdle).

However, if one or all of these movements elicits pain, it is most frequently the result of a thoracic disc lesion, because they all (to a greater or lesser degree) stretch the dura mater at the thoracic level, which is elongated in a cranial direction via the T1 and T2 nerve roots (Cyriax9: p. 202). The most sensitive test is scapular approximation (shoulders backwards, Fig. 25.6c).

Active trunk movements

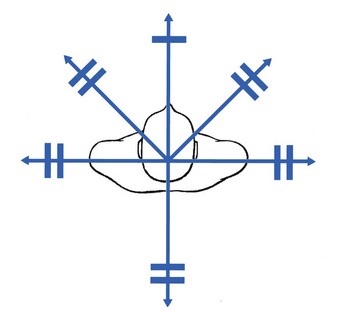

Conclusions from active trunk movements

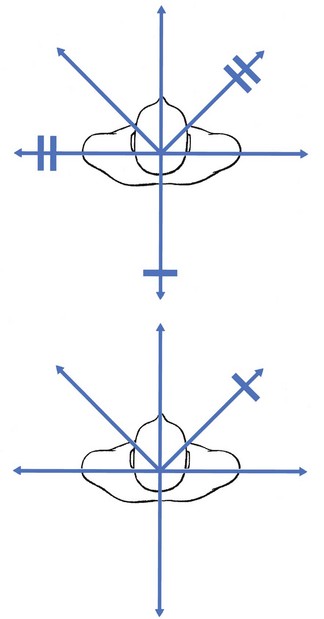

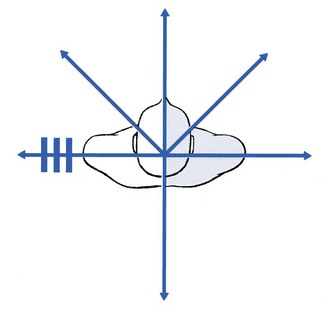

The articular pattern of the thoracic spine is an equal degree of pain and limitation of both side flexions and of both rotations, together with a larger limitation of extension and little or no limitation of anteflexion (Fig. 25.8). It resembles the pattern for the cervical spine. If this is found, a disorder of the entire segment of motion, such as in ankylosing spondylitis or osteoarthrosis, is present.

Fig 25.8 The full articular pattern.

Any other combination of abnormal tests is regarded as a partial articular pattern (Fig. 25.9). Such a combination could be, for instance, pain on one rotation or one side flexion together with one rotation, or one side flexion and extension, or three, four or five of the six movements being positive in producing pain or limitation. As long as abnormal tests are present in a non-symmetrical way, the pattern is regarded as being partial articular.

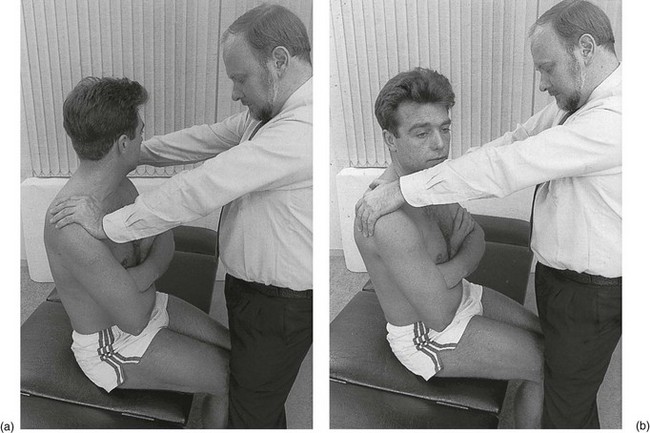

Sitting

Passive tests

Rarely, pain is present at half range, disappearing when rotation continues. This is known as a painful arc and was regarded by Cyriax9 as pathognomonic for a disc lesion when combined with a partial articular pattern.

Resisted tests

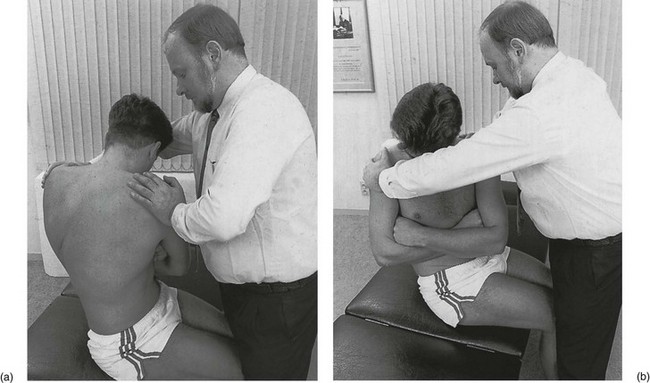

In the same position as used for the passive tests, isometric contractions are done. The patient is asked to twist the trunk to the left (Fig. 25.12a) and to the right (Fig. 25.12b) while the examiner applies counterpressure at both shoulders, so that the patient is kept immobile. Pain and weakness are noted. Because muscular lesions do occasionally occur at this level, these tests must always be performed.

Fig 25.12 Resisted rotation: (a) left; (b) right.

Cord sign: plantar reflex

The examiner glides a relatively sharp instrument along the lateral aspect of the sole, starting at the heel and moving forwards and medially towards the big toe (Fig. 25.13). Normally the toes either do not move at all or they all uniformly go into flexion. This test is pathological if the patient spreads the toes apart and the big toe moves into extension. A positive test indicates interruption of the descending motor fibres. If there is the slightest doubt about interference with the spinal cord, a full neurological examination of the lower limbs must be carried out. This includes all reflexes in the lower limbs and abdomen, resisted movements of the thigh and leg musculature, control of coordination, testing for numbness and temperature sensitivity, and the straight leg raising test.

Fig 25.13 Testing the plantar reflex.

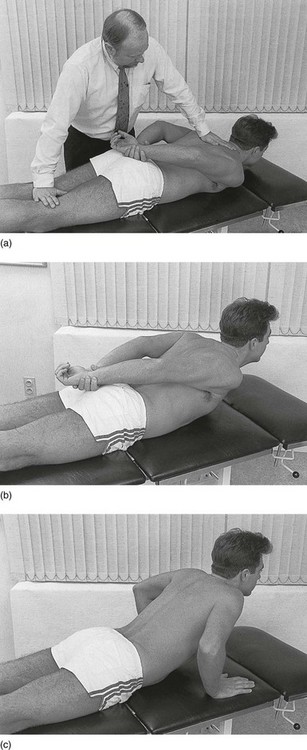

Lying prone

Location of affected level by passive extension thrust

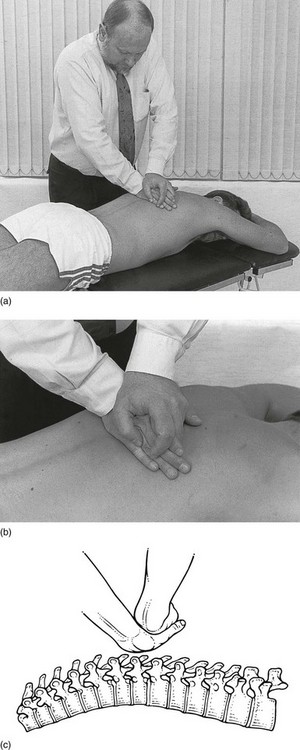

The patient lies prone and a hyperextension thrust is given over every thoracic spinous process to locate the painful level. To do this, the hand is placed obliquely, with the fifth metacarpal bone on the spinous process (Fig. 25.14). Identification of the exact level is important, because some manipulations for thoracic disc protrusions are performed specifically at the level at fault.

Fig 25.14 Passive extension thrust.

Accessory tests

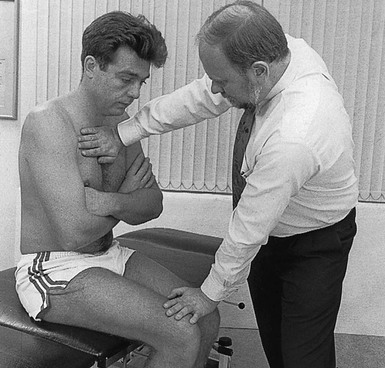

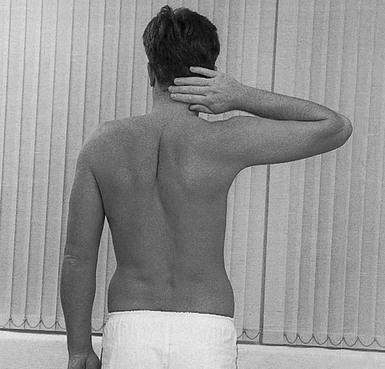

Stretching the T1 nerve root

The patient is asked to lift the arm sideways from the horizontal. The hand is now put in the neck by flexing the elbow (Fig. 25.15). This movement stretches the T1 nerve root via the ulnar nerve, which may provoke pain between the scapulae or down the arm when the mobility of the T1 nerve root is impaired. The test is useful for differentiating between a problem of the cervical spine and one of the upper thorax which interferes with the dura or the T1 nerve root: if it is painful, a thoracic problem is more likely.

Fig 25.15 Stretching the T1 nerve root.

Resisted movements and extension of the trunk

To gain more information on a muscular lesion, the following resisted movements should be performed.

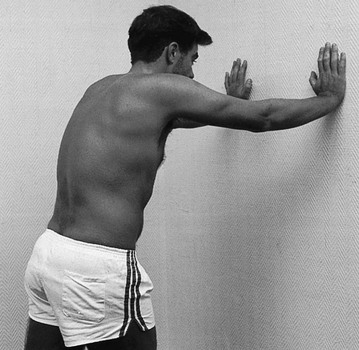

Testing the long thoracic nerve

The patient pushes against a wall with the arms stretched out horizontally in front (Fig. 25.19). If the medial edge of the scapula moves away from the thorax to produce a winged appearance, a disorder of the long thoracic nerve is present.

Fig 25.19 Testing the long thoracic nerve.

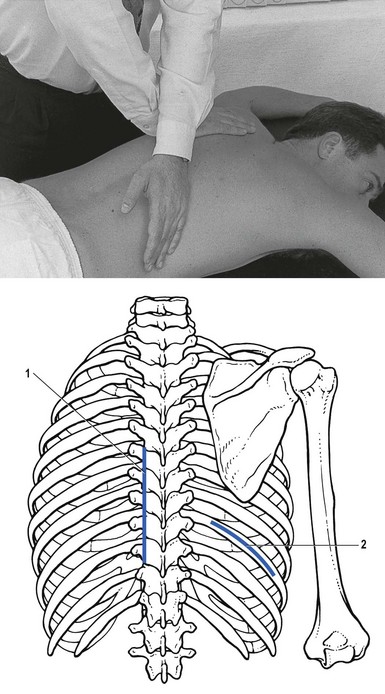

Oscillation of a rib

The examiner stands on the pain-free side and places one hand distally on the thorax, with the fifth metacarpal bone exactly on the suspected rib. The other hand rests with the pisiform bone on the contralateral transverse process of the corresponding vertebra (Fig. 25.20). Oscillations are now given by the hand resting on the rib. At the same time, the other hand is used to prevent rotation of the vertebra by pressing simultaneously on the transverse process. These oscillations influence mainly the costovertebral and costotransverse joints. When there is inflammation, pain will be provoked; when ankylosing spondylitis is present, the movement will be less elastic.

Neurological examination

The following accessory tests should be performed.

Full neurological examination of the lower limbs

This is described in Table 25.1.

Table 25.1

Full neurological examination of the lower limbs

| Tests | Nerve root |

| Inspection of gait | |

| Motor tests | |

| Resisted flexion of hip | L2–L3 |

| Resisted extension of knee | L3 |

| Resisted dorsiflexion of foot | L4 |

| Resisted extension of big toe | L4–L5 |

| Resisted eversion of foot | L5–S1 |

| Resisted flexion of knee | S1–S2 |

| Squeezing the buttocks | S1–S2 |

| Raising on tiptoe | S1–S2 |

| Reflexes | |

| Patellar reflex | L3 |

| Achilles tendon reflex | S1 |

| Sensitivity | |

| Temperature | |

| Numbness |

Technical investigations

During the last decades the use of computed tomography (CT) in combination with myelography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has greatly increased the ability to visualize thoracic spine disorders accurately. MRI is the best way to define the specific abnormality, as well as the effect on the adjacent spinal cord. CT after myelography may be useful as well, especially in those patients in whom there is involvement of the posterior ligamentous and osseous structures of the thoracic spinal canal.10

However, the superior resolution of the available imaging methods has also made the incidental detection of asymptomatic thoracic disc abnormalities more common.11 As with the lumbar and the cervical spine, it has become evident that the correlation between gross anatomical findings on MRI and clinical signs and symptoms detected by the clinician may be lacking. A significant proportion of the population has disc disease as depicted on imaging studies, yet many have no clinical findings at all.12,13 The relative frequency of asymptomatic thoracic herniated nucleus pulposus has been documented in several studies.14,15 Wood et al reviewed MRI studies of the thoracic spines of 90 asymptomatic individuals to determine the prevalence of abnormal anatomical findings: 66 (73%) had positive anatomical findings at one level or more, including herniation of a disc in 33 (37%), bulging of a disc in 48 (53%), an annular tear in 52 (58%), deformation of the spinal cord in 26 (29%) and Scheuermann endplate irregularities or kyphosis in 34 (38%).16

Awwad et al retrospectively reviewed postmyelography CT scans of 433 patients and identified 68 asymptomatic thoracic herniated discs. After comparing the imaging characteristics with a series of five symptomatic thoracic herniated discs, the authors were unable to identify any features that could reliably classify a herniated disc as asymptomatic or symptomatic.17

References

1. Grieve, G. Modern Manual Therapy of the Vertebral Column. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1986.

2. Skubic, J, Kostuik, J. Thoracic pain syndromes and thoracic disc herniation. In: The Adult Spine. New York: Raven Press; 1991:1443–1461.

3. Bechgaard, P, Segmental thoracic pain in patients admitted to a medical department and a coronary unit. Acta Med Scand. 1981;644(Suppl):87–89. ![]()

4. Edghar, MA, Nundy, S. Innervation of the spinal dura mater. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1966; 29:530–534.

5. Groen, GJ, Baljet, B, Drukker, J, The innervation of the spinal dura mater: anatomy and clinical implications. Acta Neurochir 1988; 99:39–46. ![]()

6. Nadel, JA, Murray, JF, Mason, RJ. Textbook of Respiratory Medicine, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005.

7. Pedersen, KV, Drewes, AM, Frimodt-Møller, PC, Osther, PJ, Visceral pain originating from the upper urinary tract. Urol Res. 2010;38(5):345–355. ![]()

8. Gauthier-Smith, PC, L’Hermitte’s sign in subacute combined degeneration of the cord. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1973; 36:861–863. ![]()

9. Cyriax, J. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol. 1, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

10. Rosenbloom, SA, Thoracic disc disease and stenosis. Radiol Clin North Am. 1991;29(4):765–775. ![]()

11. Vanichkachorn, JS, Vaccaro, AR, Thoracic disc disease: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(3):159–169. ![]()

12. Mink, JH, Deutsch, AL, Goldstein, TB, et al, Spinal imaging and intervention. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1998;9(2):343–380. ![]()

13. Matsumoto, M, Okada, E, Ichihara, D, et al, Age-related changes of thoracic and cervical intervertebral discs in asymptomatic subjects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(14):1359–1364. ![]()

14. Martin, DS, Awwad, EE, Pittman, T, et al, Current imaging concepts of thoracic intervertebral disks. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging 1992; 1–2:109–181. ![]()

15. Williams, MP, Cherryman, GR, Husband, JE, Significance of thoracic disc herniation demonstrated by MR imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13(2):211–214. ![]()

16. Wood, KB, Garvey, TA, Gundry, C, Heithoff, KBJ, Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine. Evaluation of asymptomatic individuals. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77A(11):1631–1638. ![]()

17. Awwad, EE, Martin, DS, Smith, KR, Jr., Baker, BK, Asymptomatic versus symptomatic herniated thoracic discs: their frequency and characteristics as detected by computed tomography after myelography. Neurosurgery. 1991;28(2):180–186. ![]()