Clinical examination of the sacroiliac joint

Introduction

Sacroiliac arthritis, both rheumatic and septic, is a common cause of unilateral gluteal pain. The sacroiliac joint is a true synovial joint and therefore subject to the same inflammatory and infectious conditions that affect other synovial joints.1,2 However, the sacroiliac joint as a primary source of mechanical backache remains controversial and diagnoses such as ‘sacroiliac dysfunction’ or ‘sacroiliac subluxation’ are ill defined and difficult to substantiate.3–5 Much of the controversy is caused by lack of agreement on clinical criteria that justify the diagnosis of sacroiliac lesions. If the diagnosis is made only on the basis of pain localization or tenderness on palpation, sacroiliac lesions will be seen frequently. If the diagnosis is based on a thorough clinical examination of lumbar spine and pelvis, sacroiliac lesions will be rare. Unilateral pain and tenderness in the region of the sacroiliac joint is usually a manifestation of the confusing phenomena of referred pain and referred tenderness from a dura mater at a low lumbar level and not a reliable clinical proof of a sacroiliac disorder.6–9 Furthermore, mechanical testing of the sacroiliac joints – exerting tension on the sacroiliac ligaments without affecting the lumbar spine and the hip joint – is not easy. Most commonly used tests lack this requirement, which may explain the differences of opinion between examiners.10–12

A discussion of the disorders affecting the joint requires definition of the following terms:

• Sacroiliac strain/sprain is overstretch or rupture of the capsuloligamentous structures as a result of abnormal joint movement.

• Sacroiliac instability is a condition of abnormal joint mobility caused by capsuloligamentous laxity.

• Sacroiliac subluxation is permanent displacement of the bony parts forming the joint.

• Sacroiliac dysfunction is a reversible decreased mobility of the joint, the result of articular causes.

• Sacroiliac arthritis is an inflammatory condition of the joint.

The concept of a ‘sacroiliac sprain’ as a common cause of backache and sciatica was introduced by Goldthwait and Osgood in 1905 and reinforced by others.13,14 It still persists. However, MacNab8 noticed that sacroiliac sprains only occur below the age of 45 and in circumstances creating considerable force on the joint, such as those generated by falls from a height or motor vehicle accidents. Cyriax7 (his p. 364) advised reserving the term for cases of pain arising from the sacroiliac ligaments in the absence of arthritis. However, difficulty arises in those examples of early sacroiliitis in which pain and clinical signs precede the appearance of radiographic sclerosis.

Clinical assessment does not differ from that described for the lumbar spine in low back pain disorders (see Ch. 36). When data from the history and functional examination suggest the possibility of a sacroiliac lesion, special tests can be performed and additional imaging studies requested.15

Referred pain

Pain referred to the region of the sacroiliac joint

Most instances are the result of lumbar disc protrusions with segmental (L1, L2, L3 and S1, S2) or multisegmental (lumbar dural) reference of pain. Arthritis of the hip joint is another possibility: pain may be felt in the inner and upper part of the buttock because of segmental reference of this joint in the third lumbar segment (see p. 11).

Pain referred from the sacroiliac joint16

The innervation of the sacroiliac joint and its ligaments is wide and complicated.17 Studies confirm that the anterior portion of the joint is innervated by the ventral rami of L5, S1 and S2, and the dorsal portions of the joint by the dorsal ramus of L5 and a plexus derived from the dorsal rami of the sacral nerves.18–20 The superior part of the joint and the iliolumbar ligaments have an L2 and L3 origin.

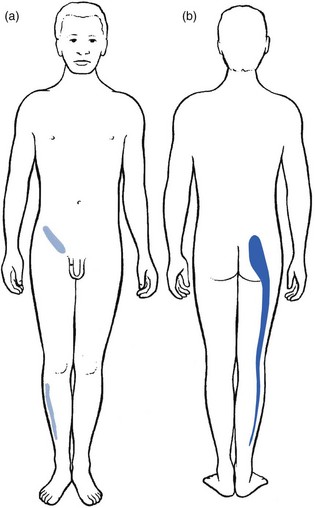

In sacroiliac strain or arthritis, pain is most often felt in the buttock, with radiation to the back of the thigh and the calf but never the foot. Often there is groin pain too.21 A typical distribution of pain is shown in Figure 41.1.22

History

History taking should cover preceding disease, trauma, pregnancy and delivery, occupation and working habits, as well as sports and recreational activities. Family and social history are of similar importance.23 In pelvic peripartum instability, the pain often starts in the third month or within the first few weeks after delivery.

In sacroiliac lesions, a typical finding is that there is unilateral gluteal pain (often deep, dull and ill defined24–26), perhaps together with reference to the S1–S2 dermatomes, chiefly the posterior thigh. Pain may alternate in the right and left buttocks which strongly suggests a manifestation of early ankylosing spondylitis, particularly when it is found in males aged between 15 and 35.

Some authors describe the adoption of an antalgic gait in painful disorders of the sacroiliac joint27,28 and a tilt of the trunk, most frequently towards the painless side.27 Some patients avoid sitting on the buttock of the affected side.28

Neurological symptoms, such as paraesthesia, weakness or numbness, are absent.

Functional examination

Introduction

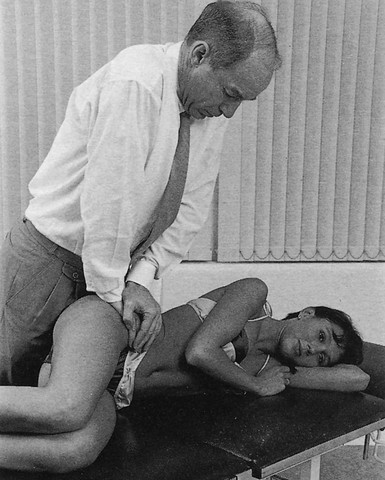

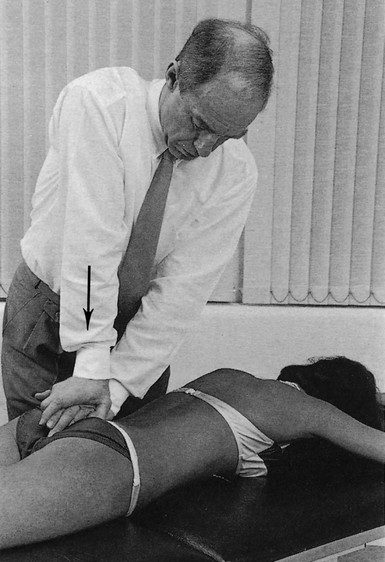

Clinical examination of the sacroiliac joint is not routinely undertaken in low back pain and sciatica, except for one test – sacroiliac distraction (see Fig. 41.3 below) – because this is the most sensitive test to detect inflammation in the joint.

Routine clinical examination of the lumbar spine can be negative but some symptoms may point in the direction of possible sacroiliac involvement because of low back pain and/or sciatica. In sacroiliac strain, the basic tests are usually not capable of evoking pain.29,30 It is only when movements really stretch the ligament and when this is prolonged that an injured ligament may react painfully. A diagnosis of ligamentous strain is thus based on the history, painful reactions after prolonged load, and the outcome of special sacroiliac tests (Box 41.1).

Sacroiliac tests

Palpation tests

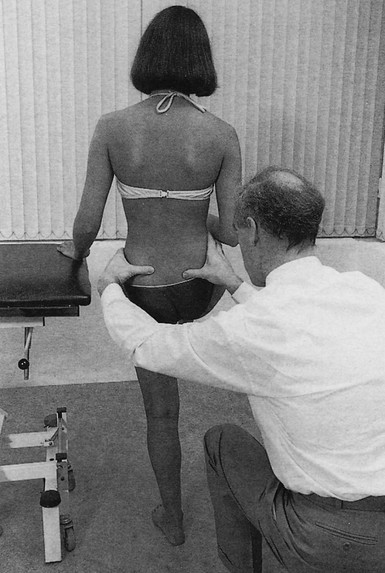

The best-known palpation tests are the standing and sitting flexion palpation tests and the Gillett test.31 The Gillett test is performed as follows.

The patient stands with the back to the examiner (Fig. 41.2), who places one thumb just underneath the posterior superior iliac spine and the other on the second sacral spinous process or on the contralateral superior iliac spine. The patient is asked to lift one knee as high as possible, which rotates the ilium on that side posteriorly and therefore moves the posterior superior iliac spine inferiorly relative to the opposite side. Fixation of the sacroiliac joint prevents this movement or, paradoxically, even gives rise to elevation of the posterior superior iliac spine as the patient compensates by tilting the pelvis at the point of maximal hip flexion. This manœuvre is usually painful in symptomatic patients.

To date, palpation tests have not demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability32–35 and therefore we do not use them.

Pain provocation tests

Pain provocation tests aim to stress the structures in an attempt to reproduce the patient’s symptoms. Studies that have examined these tests show good interexaminer agreement.36–39

• Distraction test or anterior gapping test

• Compression test or posterior gapping test

• Sacral thrust or downward pressure test

• Posterior shear or thigh trust test

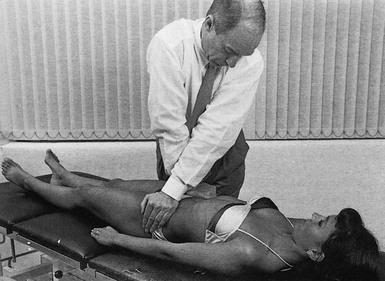

Anterior gapping test (Fig. 41.3)

This test, always performed routinely in the basic functional examination of the lumbar spine, has a high sensitivity and an almost 100% specificity for sacroiliac arthritis.40,41

Fig 41.3 Anterior gapping test.

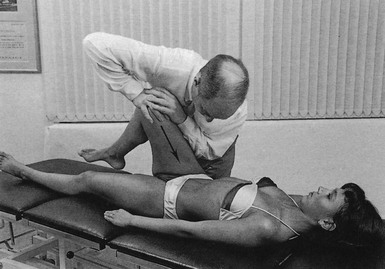

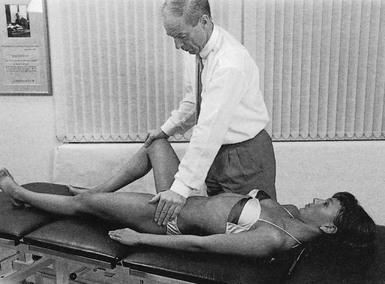

Posterior shear or thigh thrust test (Fig. 41.6)

The patient lies supine and the examiner stands on the painful side. The hip is flexed and slightly adducted. The examiner applies a posterior shearing stress to the sacroiliac joint and ligaments through the femur. Excessive (to the end-feel) adduction of the hip is avoided and the stress should be in a longitudinal direction and not towards further adduction. Some authors believe that this test in particular puts strain on the iliolumbar ligaments and that, if the thigh is maximally flexed and adducted towards the opposite shoulder, axial pressure falls on the posterior sacroiliac ligaments; if the thigh is pushed towards the same shoulder, axial pressure is believed to tense the sacrotuberal ligament.30

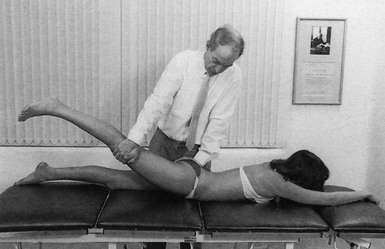

Pelvic torsion or Gaenslen’s test (Fig. 41.7)

This test is performed with the patient in a supine-lying position.42 One hip is passively flexed and pushed to the chest. The opposing leg is extended passively, hanging over the edge of the couch. Overpressure is applied to force the sacroiliac joints to their end of range: nutation on one side and counternutation on the other. The test should be interpreted with care because it also stresses the psoas muscle, the hip joints and the femoral nerve.

Fig 41.7 Gaenslen’s test.

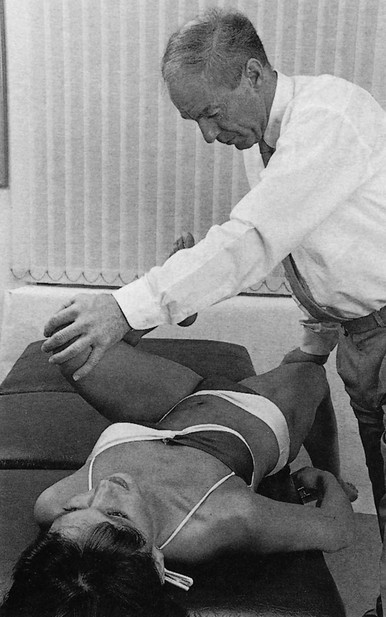

Patrick’s test (Fig. 41.9)

This test flexes, abducts and externally rotates (faber) the femur at the hip joint. After reaching the end of the movement, the femur is fixed in relation to the pelvis. The examiner holds down the anterior superior iliac spine on the opposite side and increases the pressure at the medial side of the knee. This stresses the anterior sacroiliac ligaments, on the side of the abducted leg in particular.44

Fig 41.9 Patrick’s test

• Forced lateral rotation with the leg held in 90° of flexion and resisted adduction of the thigh exert a distraction force at the sacroiliac joints and indirectly stretch the anterior sacroiliac ligaments.

• Forced medial rotation at the hip joint with the hip and knee held in 90° of flexion and resisted abduction of the thigh pull the ilium away from the sacrum. In the absence of hip joint disease, pain experienced over the sacroiliac joint is highly suggestive of a sacroiliac lesion.8

Radiology

In sacroiliac strain, nothing is revealed by the radiograph. In arthritis, radiological assessment of the sacroiliac joints is of vital importance. However, clinical signs may precede the appearance of early sclerosis by months or years (Cyriax7: p. 360). Normal appearance of the sacroiliac joint therefore does not exclude a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis. During recent decades, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become the most suitable method of detecting the early inflammation and structural damage associated with sacroiliac arthritis,45 and has an estimated sensitivity and specificity of 90%.46

References

1. Bradley, KC, The anatomy of backache. Aust NZ J Surg 1974; 44:227–232. ![]()

2. Grieve, GP. Common Vertebral Joint Problems, 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1988.

3. Dreyfuss, P, Dryer, S, Griffin, J, et al, Positive sacroiliac screening tests in asymptomatic adults. Spine. 1994;19(10):1138–1143. ![]()

4. Sturesson, B, Selvik, G, Uden, A, et al, Movements of the sacroiliac joints; a roentgen stereogrammetic analysis. Spine 1989; 14:162–165. ![]()

5. Tullberg, A, Bromberg, S, Branth, B, et al, Manipulation does not alter the position of the sacro-iliac joint. A roentgen stereogrammetric analysis. Spine 1998; 23:1124–1129. ![]()

6. Fitzgerald, RTD, Sacro-iliac strain. BMJ 1979; 1:1285–1286. ![]()

7. Cyriax, J. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

8. McNab, I. Backache. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1979.

9. Goldthwait, JE, Osgood, RB. A consideration of the pelvic articulations from an anatomical pathological and clinical standpoint. Boston Med Surg J. 1905; 152:593–601.

10. Maigne, JY, Aivaliklis, A, Pfefer, F, Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21(16):1889–1892. ![]()

11. Berthelot, JM, Labat, JJ, Le Goff, B, et al, Provocative sacroiliac joint maneuvers and sacroiliac joint block are unreliable for diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(1):17–23. ![]()

12. Slipman, CW, Sterenfeld, EB, Chou, LH, et al, The predictive value of provocative sacroiliac joint stress maneuvers in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(3):288–292. ![]()

13. Brooke, R, The sacro-iliac joint. J Anat 1924; 58:299–305. ![]()

14. Sashin, DA. A critical analysis of the anatomy and the pathologic changes of the sacroiliac joints. J Joint Bone Surg. 1930; 12:891–910.

15. Lawson, TL, Foley, WD, Carrera, GF, Berland, LL, The sacroiliac joints: anatomic, plain roentgenographic and computed tomographic analysis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1982;6(2):307–314. ![]()

16. Schwarzer, AC, Aprill, CN, Bogduk, N, The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine 1995; 20 31–31. ![]()

17. Oostendorp RAB, Elvers JWH, van Gool JJ, Clarijs JP. Segmental signs of sacro-iliac joint dysfunction. First International Symposium on the Sacroiliac Joint, Maastricht, 1991. Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

18. Grob, KR, Neuhuber, WL, Kissling, RO, Innervation of the sacroiliac joint of the human. Z Rheumatol. 1995;54(2):117–122. ![]()

19. Fortin, JD, Kissling, RO, O’Connor, BL, Sacroiliac joint innervation and pain. Am J Orthop 1999; 12:687–690. ![]()

20. Ikeda, R, Innervation of the sacroiliac joint. Macroscopical and histological studies. J Nippon Med Sch 1991; 58:587–596. ![]()

21. Reilly, JP, Gross, RH, Emans, JB, Yingve, DA, Disorders of the sacro-iliac joint in children. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A(1):31–40. ![]()

22. Jung, JH, Kim, HI, Shin, DA, et al, Usefulness of pain distribution pattern assessment in decision-making for the patients with lumbar zygapophyseal and sacroiliac joint arthropathy. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22(6):1048–1054. ![]()

23. Bellamy, N, Park, W, Rooney, PJ, What do we know about the sacroiliac joint? Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1983;12(3):282–313. ![]()

24. Inman, VT, Saunders, JB. Referred pain from skeletal structures. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1944; 99:660–667.

25. Jacobsson, H, Vesterkold, L, The thermographic pattern of the lower back with special reference to the sacro-iliac joints in health and inflammation. Clin Rheum. 1985;4(4):426–432. ![]()

26. Solonen, KA, The sacroiliac joint in the light of anatomical, roentgenological and clinical studies. Acta Orthop Scand. 1957;27(suppl):1–127. ![]()

27. Forestier, J, Jacqueline, F, Rotes-Querol, J, Ankylosing Spondylitis: Clinical Considerations, Roentgenology, Pathologic Anatomy, Treatment Translated by Desjardins AU, from La Spondylarthrite ankylosante. Masson, Paris, 1951.

28. Dunn, EJ, Byron, DM, Nugent, JT, et al, Pyogenic infections of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Orthop 1976; 118:113–117. ![]()

29. Troisier, O. Sémiologie et traitement des algies discales et ligamentaires du rachis. Paris: Masson; 1972.

30. Lewit, K. Manuelle Medizin im Rahmen der medizinischen Rehabilitation, 2nd ed. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth; 1977.

31. Gillett, H, Liekens, M. Belgian Chiropractic Research Notes, 10th ed. Huntington Beach, CA: Motion Palpation Institute; 1984.

32. Dreyfuss, P, Michaelsen, M, Pauza, K, et al, The value of medical history and physical examination in diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Spine. 1996;21(22):2594–2602. ![]()

33. Vincent-Smith, B, Gibbons, P, Inter-examiner and intra-examiner reliability of the standing flexion test. Manual Therapy. 1999;4(2):87–93. ![]()

34. Levangie, PK, Four clinical tests of sacro-iliac joint dysfunction. Phys Ther. 1999;79(11):1043–1057. ![]()

35. Riddle, DL, Freburger, JK, Evaluation of the presence of sacroiliac joint region dysfunction using a combination of tests: a multicenter intertester reliability study. Phys Ther. 2002;82(8):772–781. ![]()

36. Broadhurst, NA, Pain provocation tests for the assessment of sacro-iliac joint dysfunction. J Spinal Disorders. 1998;11(4):341–345. ![]()

37. Laslett, M, The reliability of selected pain provocation tests for sacroiliac joint pathology. Spine. 1994;19(11):1243–1249. ![]()

38. Cibulka, J, Koldehoff, D, Clinical usefulness of a cluster of sacroiliac joint tests in patients with and without low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29(2):83–89. ![]()

39. Robinson, HS, Brox, JI, Robinson, R, et al, The reliability of selected motion- and pain provocation tests for the sacroiliac joint. Man Ther. 2007;12(1):72–79. ![]()

40. Laslett, M, Aprill, CN, McDonald, B, Young, SB, Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005;10(3):207–218. ![]()

41. Levin, U, Stenstrom, CH, Force and time recording for validating the sacroiliac distraction test. Clin Biomech 2003; 18:821–826. ![]()

42. Hoppenfeld, S. Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1976.

43. Yeoman, W. The relation of arthritis of the sacroiliac joint to sciatica. Lancet. 1928; 215:1119–1122.

44. Leboeuf, C, The sensitivity and specificity of seven lumbo-pelvic orthopedic tests and the arm-fossa test. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1990;13(3):138–143. ![]()

45. Sieper, J, Rudwaleit, M, Baraliakos, X, et al, The Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68:1–44. ![]()

46. Rudwaleit, M, van der Heijde, D, Khan, MA, et al, How to diagnose axial spondyloarthritis early. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63:535–543. ![]()