Clinical examination of the lumbar spine

History

Introduction

Localization of the symptoms

• Lumbago: a sudden attack of severe low back pain, causing some degree of fixation and twinges on attempted movement.

• Backache: discomfort in the lower back.

• Sciatica: pain that radiates strictly from the buttock to the posterior thigh and calf. It is restricted to a specific dermatome (L4, L5, S1 or S2) and may be accompanied by paraesthesia and motor and/or sensory deficit. In practice, however, the term is used inaccurately if pain and paraesthesia are felt in the anterior part of the thigh and/or lower leg (L2–L3).

Pathogenesis

In lumbar spine problems, the mechanism of causation is usually reflected in the behaviour of the pain. Localization of the symptoms, their evolution and the relation to activity and posture differ according to the tissue involved. Pain in the lumbar and pelvic–gluteal area is usually of local origin but may also be referred from intra-abdominal or pelvic lesions. Sometimes lumbar pain is devoid of any organic basis and is then labelled as non-organic or ‘functional’. Local organic disorders may or may not be related to activity. The former are called activity-related spinal disorders, the latter non-activity-related spinal disorders (Box 36.1).

Non-activity-related spinal disorders (Ch. 39)

Problem solving

While taking the history, the examiner endeavours to find an answer to the following questions:

• Is this an organic or non-organic lesion?

• Do the symptoms point to activity-related disorders?

• What sort of disc lesion is present?

• What other type of lesion is more in accordance with the symptoms?

• What type of person is the patient? Is it obvious that the degree of pain and effect on daily activities tally with appearance and behaviour?

Because low back pain is most often caused by a soft tissue lesion and so is frequently attributed to disc disorders, the history serves in the first place to verify whether this is the case. ‘All discs are alike, all other lesions are different’ is Cyriax’s statement, which has been proved true in orthopaedic practice. Therefore, in disc displacements of all types, confirmation of the facts detailed in Chapter 33 is expected.

During the history the interviewer should obtain specific data on the following:

Age and activities of daily living

Sciatica caused by a posterolateral disc protrusion can be expected from adolescence to old age.

In elderly patients, lateral recess stenosis is to be more frequently expected as the cause of root pain (Table 36.1). Also, degenerative spinal stenosis is a disease that occurs predominantly in the elderly.

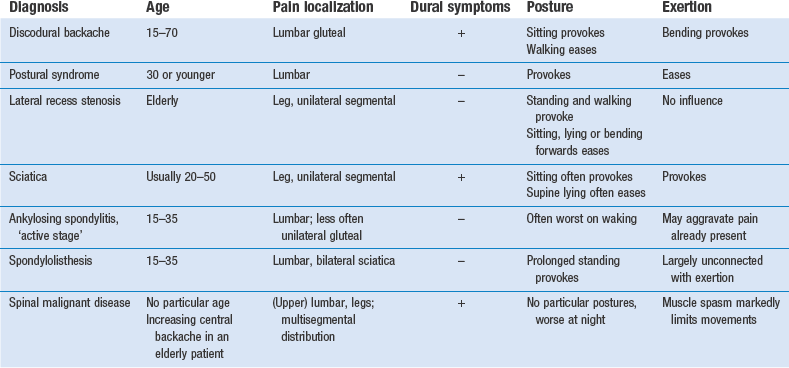

Table 36.1

| Age (years) | Disorder |

| 15 | Spondylolisthesis |

| 15–35 | Ankylosing spondylitis |

| 20–50 | Disc lesions |

| Elderly | Spinal and lateral recess stenosis |

Ankylosing spondylitis typically provokes alternating sciatica between 15 and 35 years of age. It is 4–9 times more frequent in men.1

Routine of history taking

In disorders of the lower back, symptoms can diversify. The clinician must try to obtain a clear impression not only of present discomfort but also of former events (see Box 36.4). Pain is the most common and important symptom and is usually what forces the patient to seek medical help. Other symptoms are not always mentioned spontaneously but should be asked about: the presence of paraesthesia, numbness, a cold foot or incontinence.

Pain

All the different aspects of pain should be investigated: localization, onset, evolution and duration of the perceived ‘current’ pain; influence of movement and posture; and the presence of dural symptoms. It is also very useful to obtain information on the same factors in previous attacks (Box 36.2).

Current pain

Side and level

Patients are first asked if they feel any pain at the present time and to point to its location. The method chosen may give information on emotional status. A stable patient generally places the palm of the hand at the site of maximal pain and moves it across the body to demonstrate the route of radiation. A psychologically unstable patient never touches the painful area but only points it out vaguely with the thumb.2

If the patient points to the upper lumbar area, the investigator should immediately be on the alert. Malignant diseases in the lower back have a great preference for this area (see p. 536).

Pain in one lower buttock only is rarely dural; more commonly, it is a segmental reference from S2.

Onset of pain

The next question concerns the speed of onset: ‘How did it start: was the onset sudden or gradual?’

What factors influence the symptoms?

In ‘ligamentous postural’ syndromes, pain is particularly increased by maintenance of a particular posture, whereas altering the position relieves the pain. Moreover, the longer the position is maintained, the more intense the pain becomes. Barbor3 described the discomfort of ligamentous pain as ‘the theatre, cocktail party syndrome’: it is impossible to sit at the theatre or stand at the cocktail party without low backache occurring. In contrast, the symptoms are relieved by activity. This syndrome is typically found in the young.

Another factor that may influence symptoms is raised intra-abdominal pressure during coughing and sneezing (Box 36.3). Pain in these circumstances may be a dural sign produced by sudden increased intradural pressure, which in turn causes sudden expansion of the dura pressed against the protrusion. Although it is very often related to a disc protrusion, it is clear that any space-occupying lesion in the lumbar spinal canal compressing the dura mater (e.g. a neuroma or malignant tumour) may evoke the same response. Often the patient will not mention it spontaneously, so the investigator must enquire about coughing and sneezing.

Previous attacks

Danger to S4 nerve roots

Because mobility tests for the fourth sacral roots do not exist, it is almost impossible to evaluate their function. The diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome should therefore be made entirely on the history. Patients typically present with a classic triad of (1) saddle anaesthesia, (2) bowel and/or bladder dysfunction, and (3) lower extremity weakness.4 Some patients are timid and do not mention these symptoms, so it is important to ask about them in the three types of case in which a large posterocentral protrusion is to be suspected: acute lumbago, acute perineal pain and bilateral sciatica. It should be re-emphasized that manipulation is absolutely contraindicated; even traction is not at all safe if the slightest suspicion of compression of the fourth sacral roots arises. Prompt surgery is required and any delay results in substantial morbidity.5

Inspection

• How does the patient enter the room? A posture deformity in flexion or a deformity with a lateral pelvic tilt, possibly a slight limp, may be seen.

• How does the patient sit down and how comfortably/uncomfortably does he or she sit?

• How does the patient get up from the chair? A patient with low back pain may splint the spine in order to avoid painful movements.

• What is the facial expression? Is it in accordance with the pain the patient seems to suffer?

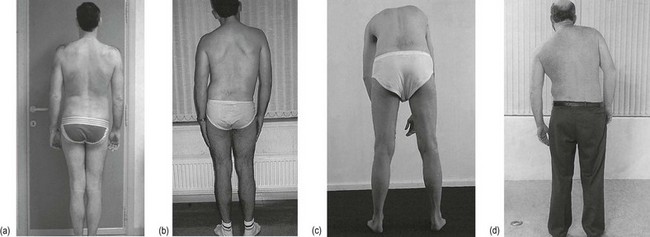

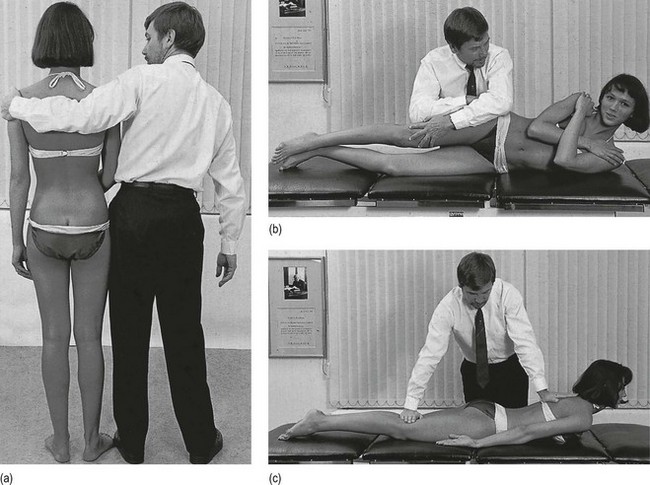

The shape of the normal trunk

The patient should be observed posteriorly and laterally. From the posterior aspect, the shoulders and pelvis should be level and equal, and the soft tissue structures on both sides should be symmetrical (Fig. 36.1a). The thoracic and lumbar vertebrae should be vertically aligned. The angles of the scapulae should be level with the seventh thoracic spinous process; the iliac crests should line up with the fourth lumbar vertebra. The lower extremities should share the body load and be in good alignment: the hip joints not adducted or abducted, knees not bowed or knock-kneed, feet parallel or toeing out slightly, and the calcaneal bones neither pronated nor supinated.

Fig 36.1 The shape of the normal trunk.

From the side (Fig. 36.1b), the thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis are observed and should have a normal curve. The pelvis should be in the neutral position, i.e. the anterior superior iliac spines lie in the same vertical plane as the symphysis pubis. Hip, knee and ankle joints should be neither flexed nor hyperextended.

The pathological trunk

Posterior view

Static scoliosis (Fig. 36.2a)

There is no clear evidence as to the significance of differences in leg length in the generation of spinal symptoms. If a platform under the shorter limb eases or even abolishes the pain while standing or on lumbar flexion or extension, a raised heel is advised. Some physicians recommend correction of any kind of leg length inequality. However, most investigators agree that mild leg length inequality of up to 15 mm is not a factor that contributes to low back pain.6,7 Correction is therefore only of importance in recurrent attacks of lumbago and in the presence of a difference of more than 15 mm.

Sciatic scoliosis (Fig. 36.2b)

In lumbar disc displacements, six possible types of deviation (sciatic scoliosis) exist:

• Towards the painful side. This shows that the displacement is situated medially, i.e. at the axilla of the nerve root.

• Away from the painful side. In this case, the protrusion lies lateral to the nerve root, which is drawn away by the deviation of the trunk.

• Alternating deviation. This demonstrates that the dura mater slips from one side to the other of a small midline protrusion. It is also diagnostic of a protrusion at the fourth lumbar level.

• Deviation on standing, which disappears during flexion.

• No deviation when standing erect but marked deviation on attempted trunk flexion. This is often seen in root pain.

• A momentary deviation when the trunk is flexed halfway. The patient is seen to deviate suddenly at a particular moment during flexion, returning to a symmetrical posture as this point is passed. Usually pain is felt at the moment of deviation but occasionally it is not. This sign indicates that a fragment of disc alters its position at the back of the intervertebral joint and temporarily touches the dura mater.

Lateral view

Excessive lordosis

If this is not compensated by an equally excessive thoracic kyphosis, it is suggestive of spondylolisthesis. The whole spine lies in a plane anterior to the sacrum. This is characterized by a mid- or low-lumbar shelf at the spinous processes which, if not visible, can be palpated: when the hand slides gently downwards along the spinous processes, it engages the step at the fourth or fifth level (Fig. 36.3b). In concealed spondylolisthesis the shelf disappears during recumbency, and radiography in this position may not reveal the displacement.

Muscles

Wasting

In severe arthritis of the hip, the buttock, hamstrings and quadriceps will show visible wasting.

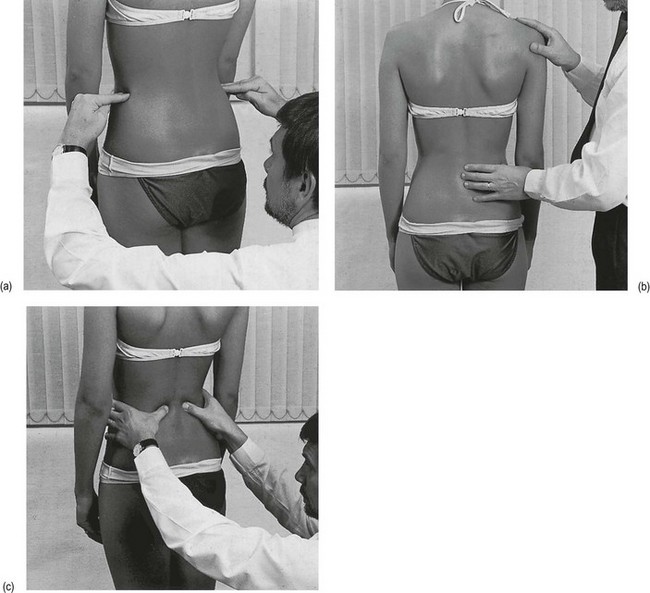

Spasm

Asymmetric spasm of the paraspinal or gluteal muscles, making them stand out compared to the normal side, is an ordinary finding in discodural or discoradicular problems, and is then accompanied by an adaptive posture in flexion or in side flexion. In mild cases, the difference in tension can be palpated (Fig. 36.3c). Muscle spasm, accompanied by visible flexion and/or lateral deformity, is also an unfavourable sign in sciatica. The protrusion nearly always proves irreducible.

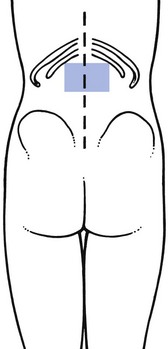

Functional examination

Before the examination of lumbar movements is begun, the patient should be asked if there is any pain at this moment and to point out its site. If he or she indicates the upper lumbar/lower thoracic area, the examiner should be on the alert. Disc lesions at this spot are extremely rare but serious non-activity-related disorders are often situated here. Therefore the area is called the ‘forbidden’ area (Fig. 36.4).

Fig 36.4 The ‘forbidden’ area.

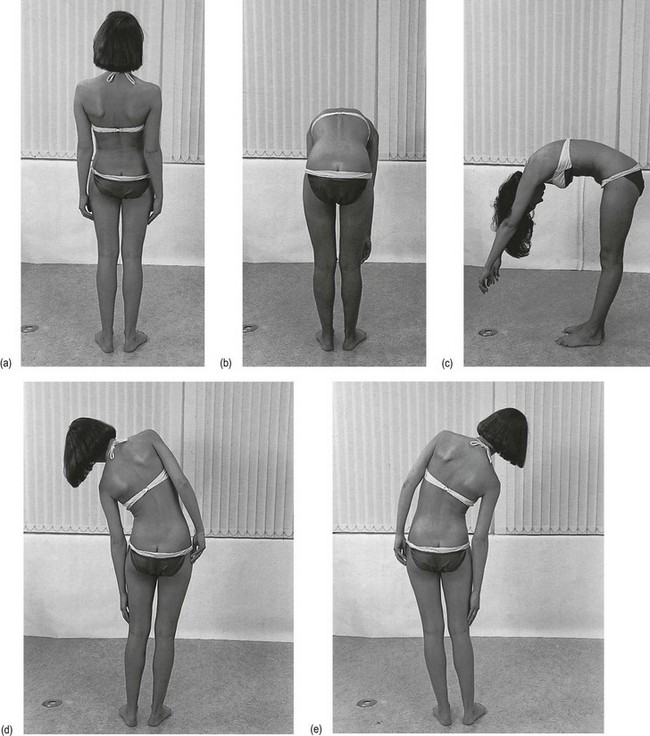

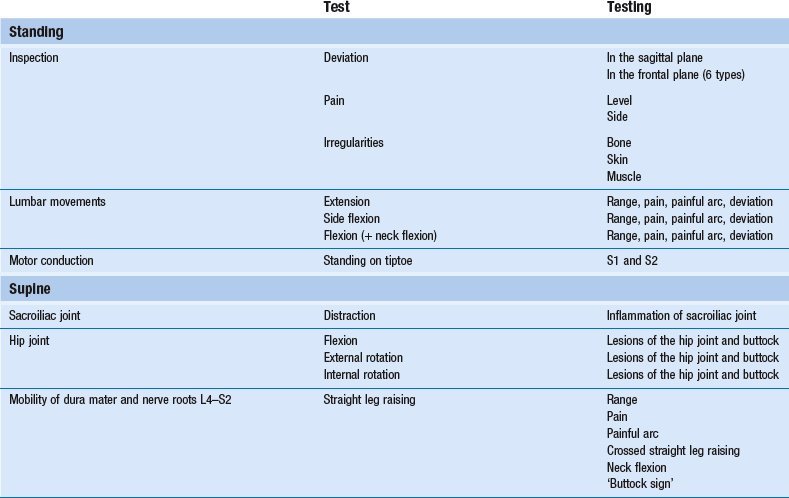

Examination standing

Procedure

Four active movements are examined while the examiner watches the patient from behind: backward bending, side bending to each side and forward bending completed at full range by neck flexion (Fig. 36.5).

• Extension is recorded by noting the accentuation of the lumbar curve, as well as how far the patient can lean back before the pelvis tilts.

• Lateral flexion is measured by determining how far the patient can run the hand down the side of the leg. At full range the lumbar spine should be curved uniformly in both directions. The patient is not allowed to bend forwards or backwards while performing the movement.

• The range of forward flexion is assessed by noting the distance of the fingertips from the floor. When complete body flexion has been attained, the lumbar spine is flattened or in young people even slightly convex. Forward bending is usually the most restricted and painful movement and may leave a persistent ache obscuring the responses to other movements. It is therefore preferable to examine this movement last. However, in ligamentous disorders and in stenosis of the spinal canal, bending forwards may be pain-free or may cause only minor discomfort.

Findings

After the four lumbar movements have been tested, one of the following patterns may emerge:

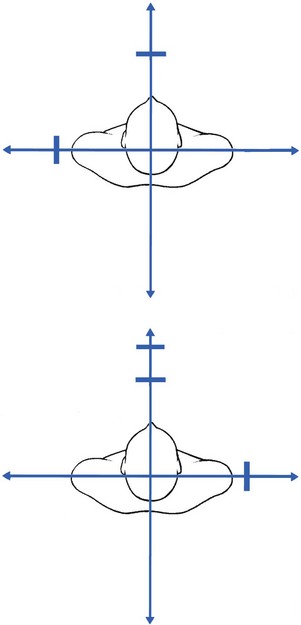

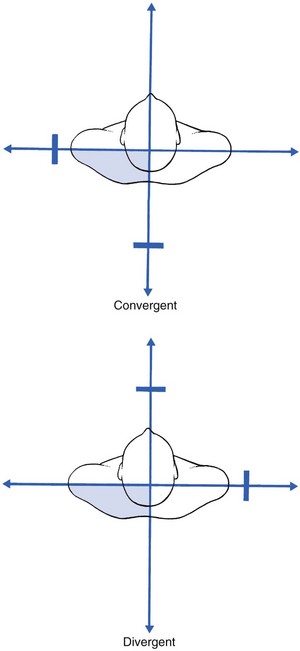

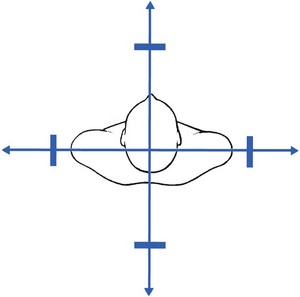

Partial articular pattern

This is very suggestive of internal derangement and strongly suggests a disc protrusion. One or more of the lumbar movements are painful, whereas the others are not, or are less painful (Fig. 36.6). If there is limitation of range, its degree is unequal and corresponds with the degree of pain.

Pain at the end of movement

In a capsular lesion of one of the apophyseal joints, movements also cause pain at the end of the range but now a convergent or divergent pattern is to be expected. This means that in a left-side joint, extension and side flexion to the left or flexion and side flexion to the right are painful (Fig. 36.7).

Full range, without pain

• History of a lumbar disc lesion but without displacement at the time of examination. This is a well-known event in patients presenting with a self-reducing type of disc lesion. Every morning the patient awakes comfortable and is able to bend the back in every direction without any pain. After some hours the back begins to ache. If such a patient is seen early in the morning, all clinical tests are negative. Another example is the patient who is seen some days after an attack of acute lumbago. Because of spontaneous recovery, all symptoms may have been lost and no disc protrusion is present at the time of examination.

• Pain referred to the back in the case of visceral disease. If the history reveals that pain is not aggravated by activity or relieved by rest, a non-activity-related disorder should be suspected.

• Ligamentous postural syndrome. The pain is only provoked after standing or walking for a long time. Spinal movements are painless for the simple reason that the stress applied during the tests is not sufficient to induce pain.

• Spondylolisthesis without a disc lesion. This disorder resembles the ligamentous postural syndrome but patients may complain of bilateral sciatica as well. Inspection often shows a mid- or low-lumbar shelf.

• ‘Bruised’ dura mater or dural sleeve. These patients have started with an ordinary attack of lumbago and/or sciatica. There is a constant ache in the back or the limb, unaltered by movement or posture and most often worse at night. Epidural local anaesthesia abolishes the symptoms, which proves the dural origin.

• Spinal stenosis. The typical history is that of pain coming on during standing and walking. Lumbar movements, except perhaps extension, do not provoke the pain. If the patient is asked to stand for a while, pain arises in the back and limbs, disappearing again on flexion.

Interpretation

Extension

Painful limitation and full articular pattern

In lateral recess stenosis, extension may provoke pain and/or paraesthesia in one leg only.

Side flexion

• In a muscular lesion or fracture of a transverse process, pain arises from stretching (bending to the contralateral side). Resisted side flexion in the opposite direction is also painful.

• In unilateral posterior ligamentous dysfunction syndrome, painful side bending towards the contralateral side suggests a lesion of either the iliolumbar ligament or the capsule of a facet joint. In the former, anteflexion and extension may also be painful. A facet joint lesion shows a divergent pattern: as well as side flexion, forward flexion is also painful at the end of range.

Flexion

Bending forwards causes pelvic rotation together with flexion of the lumbar spine. Normally, a smoothly graded ratio exists between the degree of pelvic rotation and that of lumbar flattening. This constitutes the ‘lumbar–pelvic rhythm’, which is difficult to quantify. However, at any phase of body flexion, the extent of lumbar curve flattening must be accompanied by a proportional degree of pelvic rotation around the transverse axis of the two hip joints. During these movements, a posterior shift of the hips in a horizontal plane takes place simultaneously, in order to maintain balance, an integral part of the pelvic portion of the lumbar–pelvic rhythm. The rhythm is disturbed if any of the component parts lacks function.8

A painful arc on flexion always means that a fragment of disc shifts, jarring the dura mater halfway through the movement.9 The pain disappears when the patient continues forward bending.

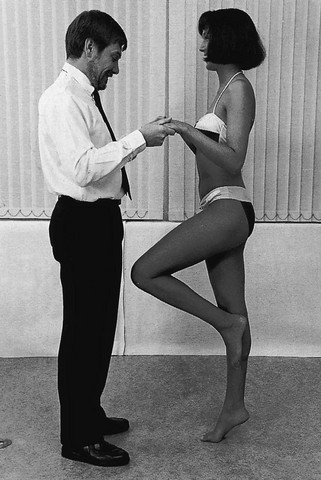

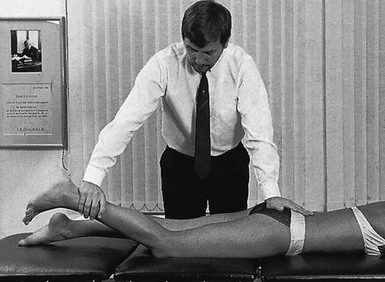

Standing on tiptoe

The last test in the standing position is standing on tiptoe, which examines the strength of the calf muscles and thus the integrity of the S1/S2 segment. The patient is invited to perform the test, first on the good leg and then on the bad. The examiner steadies the patient with both hands, without taking any of the weight (Fig. 36.9). Inclining the body forwards and flexing the knee is evidence of weakness.

Fig 36.9 Standing on tiptoe.

This test is best repeated several times in order to discover those cases with only slight weakness.

Examination supine

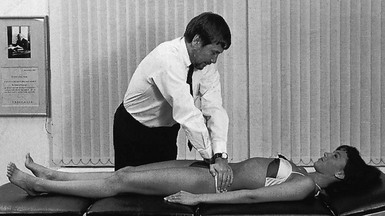

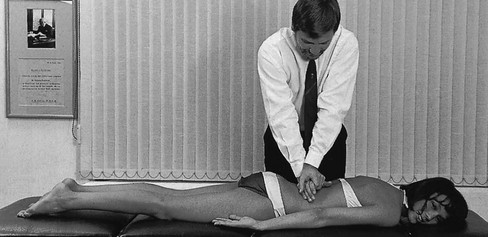

Sacroiliac joints

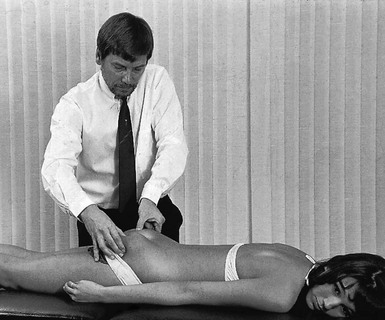

Pain in the buttock most often results from disorders of the lumbar spine. However, pain from hip and sacroiliac disorders is referred to the same area. To exclude sacroiliac disorders, a specific test should be done to exert tension on the capsule and ligaments of the sacroiliac joint without affecting the lumbar spine or the hip joint. Distraction of the iliacs seems to be the best scanning test that fulfils this condition.10 It is performed as described below.11

The examiner places the hands on the anterior superior spines of the ilium with the arms crossed (Fig. 36.10). Pressure is exerted in a downward and outward direction and should be evenly distributed to prevent moving the lumbar region.

Fig 36.10 Testing the sacroiliac joints.

The distraction test at the sacroiliac joint has very high specificity and 100% sensitivity.12 The test is extremely important in the clinical diagnosis of back pain and should never be omitted; there is almost nothing in the nature and extent of sacroiliac pain that distinguishes it from a disc protrusion compressing either the dura mater or the dural extent of the S1 and S2 nerve roots. The fact that the pain probably comes and goes irrespective of posture and exertion, or often changes sides, draws attention to the possibility of sacroiliac arthritis. To make matters more confusing, coughing also hurts because the increase in abdominal pressure painfully distracts the ilium from the sacrum. Also, routine clinical examination does not usually differentiate sacroiliac arthritis from a disc lesion: the lumbar movements may increase the pain a little at full range; flexion can be very painful and even limited; and straight leg raising may also prove to be painful. It should therefore not be surprising that the diagnosis is easily missed and that patients are often treated on the assumption that a disc lesion is present, which may even lead to unnecessary surgery. Moreover, a normal radiographic appearance of the sacroiliac joints does not always exclude arthritis, as symptoms may precede the radiological evidence by months or even years. It is therefore vital never to forget the sacroiliac distraction test during routine lumbar examination.

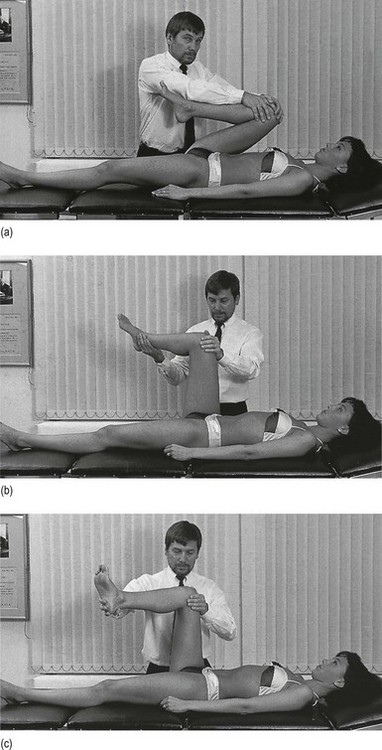

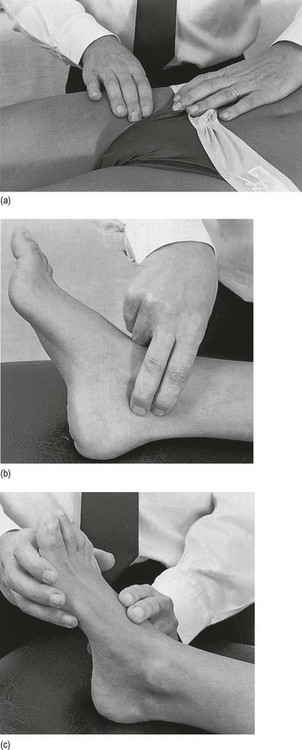

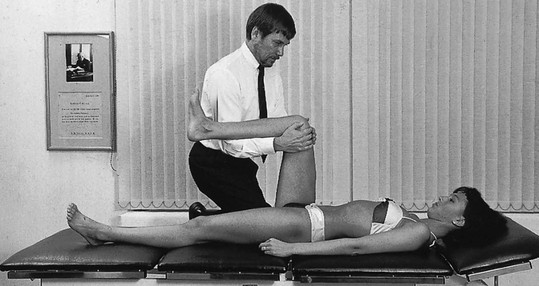

Hip joints

The thigh is moved into flexion until it touches the abdomen (Fig. 36.11a). The movements of rotation are tested while the hip joint is held in 90° of flexion. One hand stabilizes the femur at the knee, while the other is placed at the distal end of the lower leg and performs the rotation movement (Fig. 36.11b, c).

In minor lumbar lesions, none of these movements usually hurts at the back. In a patient with severe lumbar pain, however, some of these tests can be slightly painful. Full hip flexion, for instance, may exert slight traction on the sciatic nerve roots. Also, full medial rotation stretches the sciatic nerve trunk and may cause an ache in the buttock.13 The same applies to the sacroiliac joints. Moving the hip joint beyond full range involves the next link of the moving chain – the sacroiliac joint – and may evoke sacroiliac pain. Full lateral rotation at the hip stretches the anterior sacroiliac ligaments and full medial rotation has the same effect on the posterior ligaments (see Ch. 43).

Straight leg raising test

Historical note

This test was first presented by JJ Frost in 1881 with reference to his teacher, Ernest Charles Lasègue. Frost proposed the test as an aid in distinguishing hip from sciatic pain.14 Later, a number of workers13,15–17 demonstrated that this movement exerts tension on nerve roots and dural tube. The mobility of the nerve roots at the intervertebral foramen has also been investigated and shows a range of 2–8 mm on SLR.18–20 Careful study21 of subjects between 35 and 55 years of age showed a downward movement of 1.5 mm for the fourth lumbar root, 3 mm for the fifth lumbar root and 4 mm for the first sacral root. A more recent study on fresh cadavers showed the intrathecal movement of the lumbosacral roots induced by SLR of 70° to be 0.96 mm, 1.54 mm and 2.31 mm for roots L4, L5 and S1, respectively.22

Significance of the test

In a study of 50 consecutive surgical patients with clinical and radiographic evidence of lumbar disc herniation, it was shown that SLR was the most sensitive preoperative physical diagnostic sign (96%) for correlating intraoperative pathology of lumbar disc herniation.23 The sign has also been helpful in diagnosing discodural backache.24,25 However, the significance of neither the presence nor the absence of the signs should not be overestimated.26,27 SLR as an isolated phenomenon has no diagnostic significance and must always be interpreted in association with other clinical findings. As can be seen in Box 36.5, limitation of the mobility of nerve roots and dural tube is not pathognomonic for a disc lesion.

• Cases where the nerve root emerges a little higher up in the foramen and does not come into contact with the protrusion

• Protrusions at the second or third lumbar level and the third or fourth sacral nerve roots, which are not influenced by the manœuvre

• Minor protrusions that interfere only slightly with the dura mater and therefore do not influence its mobility.

Disc lesions at the second or third lumbar level

In these lesions, SLR is usually of full range because the movement does not directly interfere with these roots.18 However, full SLR may aggravate lumbar pain through traction exerted on the dura via the roots below.

Painful disorders of the sacroiliac joint

Straight leg raising may also be painful, though not limited, in sacroiliac disorders. At full range, traction through the tightened hamstrings is exerted on the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments, and the anterior capsule of the joint.28

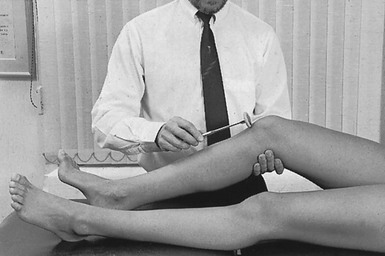

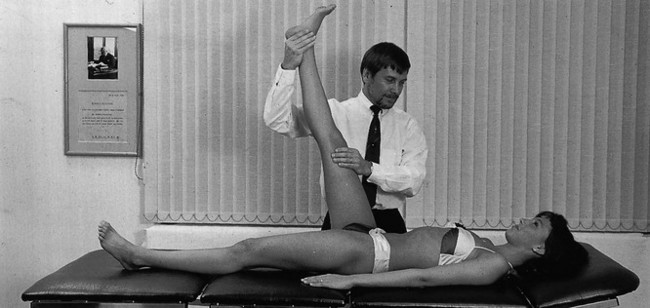

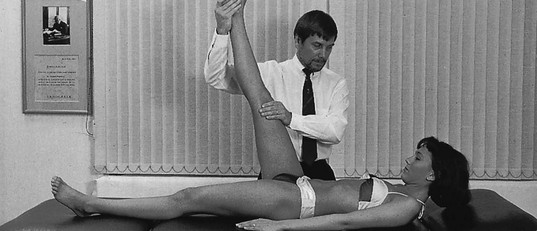

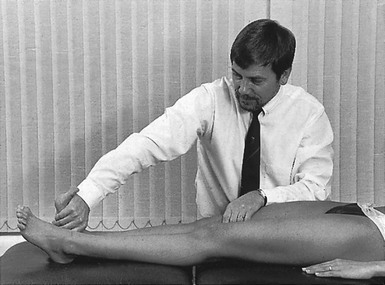

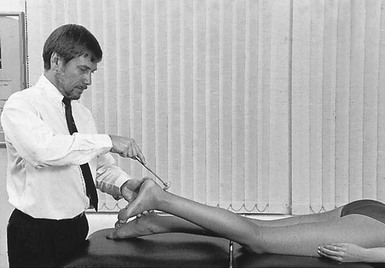

Performing the test

Before testing, it should be assumed that there is at least 90° of flexion at the hip joint; otherwise conclusions cannot be drawn. Then the leg is lifted upwards from the anatomical position by supporting the foot at the calcaneus. To prevent the knee from bending, the other hand is placed on its anterior aspect (Fig. 36.12). The patient should also not be allowed to rotate the pelvis forwards or to abduct and externally rotate the leg at the hip, in order to escape painful stretching.

Fig 36.12 Straight leg raising.

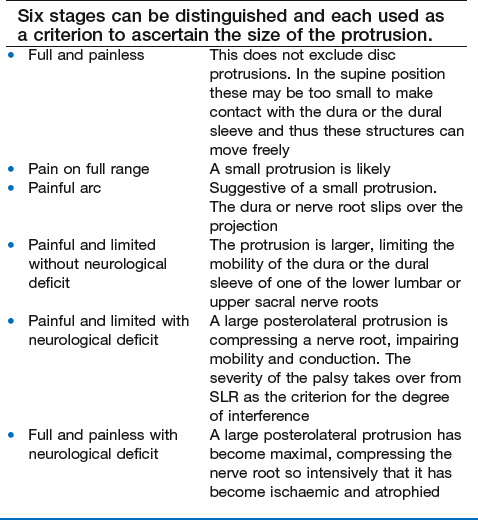

The degree of limitation varies with the degree of the discodural or discoradicular interaction. However, this rule only holds as long as there is no parenchymatous involvement. As soon as there are detectable neurological sings, SLR becomes independent of the degree of discoradicular interaction. (See Box 36.6 for an outline of the six stages in the SLR test.)

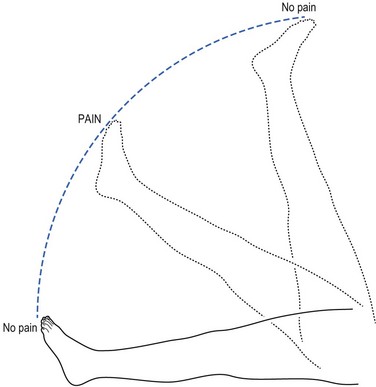

Cross-leg straight leg raising test

This test is positive when moving the uninvolved leg reproduces the back or sciatic pain. This results from movement of the dura and the contralateral nerve, which is dragged downwards and medially.29 It strongly suggests an axial localization of the protrusion and points to the fourth lumbar level30 but some31,32 have failed to correlate the position of the disc protrusion in relation to the root at laminectomy. However, a very high incidence of sequestration or extrusion is seen at operation in patients with cross-leg pain (Fig. 36.14).26,33,34

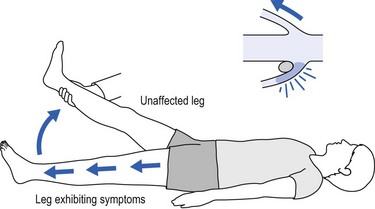

Straight leg raising with neck flexion

At the moment SLR becomes painful, the patient is asked to flex the neck, while keeping the trunk still. This often increases the pain by pulling on the dura mater from above, adding tension to the impaired dural structures.35 This clear ‘dural sign’ excludes the possibility of a major sacroiliac buttock or hamstring lesion (Fig. 36.15).

Fig 36.15 Modified straight leg raising: with neck flexion.

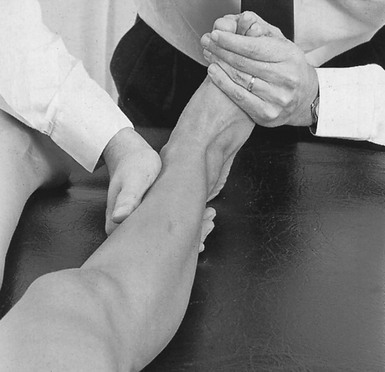

The presence of nerve irritability can also be confirmed with the manœuvre known as Bragard’s test. The raised leg should be lowered until pain is relieved. In that position the foot is dorsiflexed, which causes a recurrence of pain as a result of stretching the sciatic nerve via the tibial nerve.36,37

This is also suggested to be a very reliable test of root tension.15 In this manœuvre, SLR is carried out until pain is reproduced. At this level, the knee is slightly flexed until pain abates. The patient’s limb is rested on the examiner’s shoulder and the patient’s thumbs are placed in the popliteal fossa, over the sciatic nerve. If sudden firm pressure on the nerve gives rise to pain in the back or down the leg, the patient is almost certainly suffering from significant root tension.

Lumbago and straight leg raising

The degree of limitation corresponds to the degree of discodural contact.22 In large posterocentral protrusions, SLR is limited bilaterally. Unilateral lumbago often restricts the manœuvre on the affected side only or to a greater degree on that side than on the other.

Sciatica and straight leg raising

The SLR test is very useful to ascertain the degree of discoradicular compression.23 If the root is not yet atrophic, the degree of restriction of SLR is proportional to the pressure exerted on the nerve root. However, from the point at which conduction becomes impaired, which is coupled with neurological signs, the degree of interference affords the new criterion of the size of the protrusion. Indeed, although the protrusion has become larger, restriction of SLR may not have altered or may even have returned to full range. In the latter case, the patient has developed an ischaemic root palsy. The protrusion has become maximal in size but, as a result of the ischaemia, the nerve root has lost its function, including that of pain conduction. Dural sleeve pain thus ceases and SLR returns to full range. The patient is subjectively better – pain-free – but the lesion is anatomically worse. The large protrusion will undoubtedly be seen on computed tomography (CT), although the SLR test has become negative (see Box 36.6).

Non-organic disorders and straight leg raising

However, the inconsistencies likely in psychogenic disorders should be recognized, in order to avoid treatment of a spinal lesion that does not exist. If there is any doubt, additional tests should be performed to establish these inconsistencies. For example, if the patient sits on the couch with the legs outstretched in front, discrepancy between the degree of alleged limitation of SLR and the degree of hip flexion needed to be able to sit on the couch confirms the suspicion (see online chapter Psychogenic pain).

Testing the integrity of spinal segmental innervation

Diffuse weakness of all muscle groups, particularly the psoas muscle, is highly suggestive of a psychological disorder.2,30

Tests of motor conduction

There are four tests in the supine position.

This tests the L2 and L3 nerve roots. It is performed with the hip joint flexed to 90° so as to eliminate activity of the rectus femoris as much as possible. Both hands are placed at the distal end of the thigh and the patient attempts to resist the strong force applied by the examiner (Fig. 36.16). At the same time, it is necessary to stabilize the ilium with one knee placed against the patient’s ischial tuberosity.

Fig 36.16 Resisted flexion of the hip.

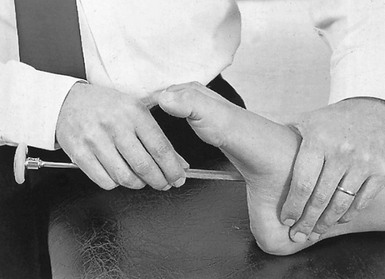

Resisted dorsiflexion of the foot

This tests the L4 nerve root. The patient lies supine with the hips and knees extended. The patient holds the ankle in full dorsiflexion and should resist the full weight of the examiner’s body (Fig. 36.17).

Fig 36.17 Resisted dorsiflexion of the foot.

Resisted dorsiflexion of the big toe

This tests the L4 and L5 nerve roots. The examiner places the thumb on the nail bed of the great toe and the fingers on the ball of the foot. The patient is asked to resist the examiner’s attempt to plantiflex the great toe (Fig. 36.18).

Fig 36.18 Resisted dorsiflexion of the big toe.

This tests the L5 and S1 nerve roots. One hand stabilizes the ankle at the medial side, while the other hand is placed at the outer side of the forefoot. The patient is asked to resist the examiner’s attempt to move the foot into dorsiflexion and inversion (Fig. 36.19). When weakness is present, the examiner needs to be aware of efforts to substitute the eversion movement by rotating the leg outwards at the hip.

Fig 36.19 Resisted eversion of the foot.

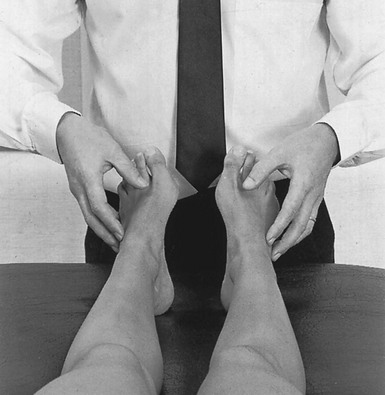

Tests of sensory conduction

These are performed next. The various areas are compared bilaterally at the same time (Fig. 36.20):

Fig 36.20 Testing for sensory conduction.

Testing the integrity of the spinal cord

• Root palsy affecting more than one root, especially if this is bilateral.

• Backache in the upper lumbar area.

The reverse end of the reflex hammer is run firmly over the plantar surface of the foot from the calcaneus along the lateral border to the forefoot, ending at the ball of the great toe (Fig. 36.22). In a positive reaction the great toe extends, while the other toes plantarflex and splay (positive Babinski’s sign).

Fig 36.22 Testing for Babinski’s sign.

Examination of the circulation

This is optional and depends on the history and findings at inspection.

If intermittent claudication is suspected, the pulses of the femoral, posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis arteries should be felt (Fig. 36.23). If the pulse is diminished or absent at the femoral artery, the diagnosis is almost a certainty. Absence of a pulse at the ankle often exists without any vascular disorder.

Examination in the prone-lying position

This starts with the ankle reflex test.

Ankle reflex test

The foot is raised with one hand. Then all the slack of the plantiflexors is taken up by the little finger pushing the foot into dorsiflexion, before striking the Achilles tendon (Fig. 36.24).

Fig 36.24 Ankle reflex test.

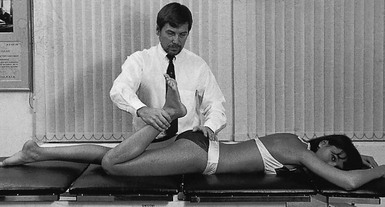

Passive knee flexion

Next, passive knee flexion is performed to test the mobility of the third lumbar root (Fig. 36.25).38

Fig 36.25 Passive knee flexion.

In posterolateral disc protrusions at this level, flexion of the knee is painful at its extreme and occasionally limited in range. Pain is felt in the back and/or the anterior part of the upper leg, depending on whether the test provokes a discodural or a discoradicular interaction. Wasserman described the manœuvre in 1918. It was performed in soldiers with anterior thigh and leg pain where the SLR test was negative.39

A false-positive femoral stretch test has also been reported in osteoarthritic hip joints, diabetic neuropathy, anticoagulant medication, retroperitoneal haemorrhage and ruptured aortic aneurysm.40,41

Crossed femoral stretching test

This test is considered positive when flexion of the knee on the asymptomatic side reproduces the symptoms on the affected side. It is hypothesized to be a valid manœuvre to assist in the diagnosis of symptomatic disc herniation.42 However, it is a far less constant sign, and in most third lumbar root lesions stretching is painful but not limited.

Testing motor conduction

There are three tests in the prone-lying position.

Resisted extension of the knee

This tests the L3 nerve root. The examiner tries to resist attempted extension with his or her flexed elbow, at the same time fixing the upper leg strongly just above the knee (Fig. 36.26). The normal patient is stronger than the examiner. Gross weakness goes together with weakness of the psoas, which is partly supplied by the same nerve root. If weakness is bilateral, spinal neoplasm or myopathy should be suspected.

Fig 36.26 Resisted extension of the knee.

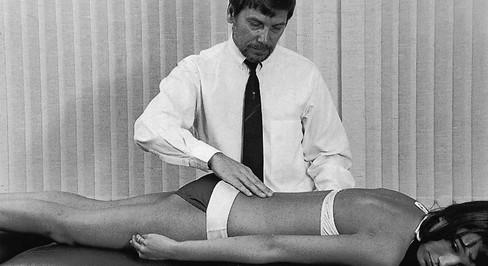

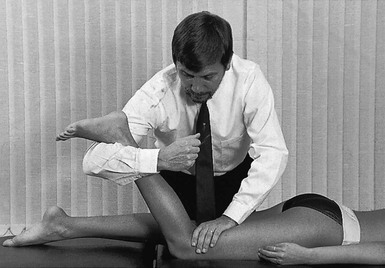

Resisted flexion of the knee

This tests the S1 and S2 nerve roots. The examiner resists attempted flexion at the same time as stabilizing the pelvis (Fig. 36.27). Normally, the examiner is just stronger than the patient. Weakness indicates a lesion of the first or second sacral root.

Fig 36.27 Resisted flexion of the knee.

Painful weakness indicates partial rupture of one of the hamstrings.

Palpation

To detect irregularities of the lumbar spinous processes

The index and middle fingers run quickly down the spine feeling for any abnormal projections (Fig. 36.29). If one is found, it may indicate wedging of a vertebral body or complete loss of two adjacent disc spaces. It should also prompt suspicion of bone erosion of a vertebral body (osteoporosis, tuberculous caries, secondary deposit or an old fracture), which requires radiography.

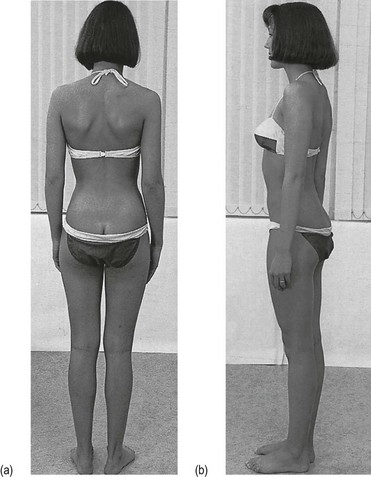

Pressure towards extension

Next a series of pressures towards extension are exerted to detect the level of the lesion. Starting at the sacrum, each lumbar segment is ‘sprung’ in turn, and it should be noted at which level pain and muscle guarding are most provoked (Fig. 36.30).

Fig 36.30 Pressures towards extension.

A hard end-feel in patients under 40 years old suggests ankylosing spondylitis.

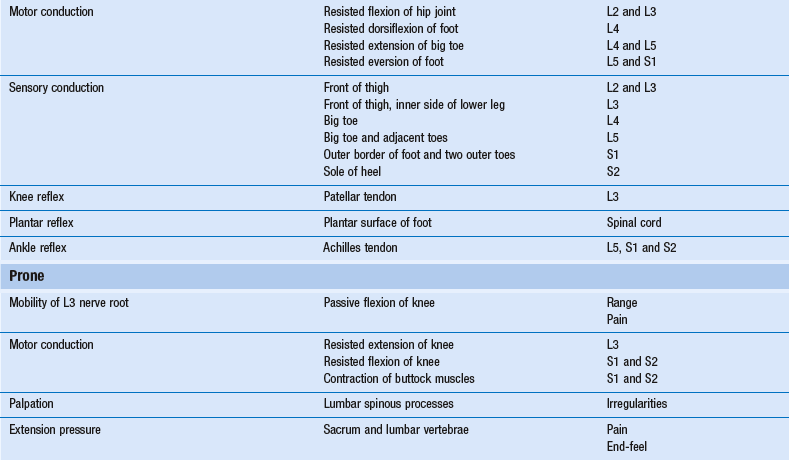

Functional examination and palpation are summarized in Table 36.3.

Accessory tests

• A fracture of the last rib or a transverse process is suspected: local pain following unilateral injury to the lumbar spine. Pain is generated on side flexion away and resisted side flexion towards the painful site. Radiography confirms the diagnosis.

• A muscle sprain is suspected: at the lumbar region this scarcely ever occurs. It is only the combination of painful resisted extension with painless passive extension that directs attention to the muscle. However, in some (acute) disc lesions, resisted movements may also provoke pain because of increased compression of the joint.

• The patient is suspected of psychogenic symptoms: pain that is provoked by resisted movements is likely to occur here, because these patients tend to equate effort with pain.

Epidural local anaesthesia

A weak solution of procaine can be introduced epidurally via the sacral route. The solution desensitizes the dura mater and the dural investments of the nerve roots. In a discodural or discoradicular interaction, the pain will cease for the duration of the anaesthesia. In addition, epidural local anaesthesia induced for diagnostic purposes may also yield permanent improvement (see p. 566).

Alternatively, if a disorder of the posterior lumbar elements (facet or ligaments) is probable, local anaesthesia of the suspected structure should be performed. Five minutes after infiltration, the patient is asked to undertake the movements that were previously painful. If these no longer cause distress, the correct area has clearly been chosen and the diagnosis is confirmed. The infiltration must be precise, however, as false inferences may be drawn, a fact that is especially true for infiltration of the facet joints. It has recently been shown that, when relatively large volumes are injected into the facet joint, some extravasation occurs through the thin anterior capsule into the epidural space.43 Facet arthrography confirms that epidural extravasation of dye takes place when more than 2 mL is injected in the facet joint.44 More than this amount of local anaesthetic injected into a facet joint may thus result in an unintentional epidural block.

Technical investigations

Plain lumbar radiography

Most observations made on plain radiographs are of little or no value.45,46 In particular, congenital anomalies, such as transitional vertebra, occult spina bifida and asymmetric facet orientation, are not clinically significant.47

It has also been repeatedly shown that there is no relationship between clinical symptoms and radiological changes associated with degeneration.48–55 The poor diagnostic value of radiographs in patients with low back pain can also be appreciated from the observation that radiographs of the individual with symptoms remain unchanged over time, despite the fact that the symptoms come and go. Because radiographs do not show the position of cartilage, they are of no value in diagnosing current disc lesions either. Radiographs therefore remain a very poor method of indicating causes of past, present or future low back pain.56

It is common practice to order routine radiographs to reduce the risk of missing serious disorders. The possibility is in fact slight, and one series of 68 000 spinal radiographs found only 1 in 2500 with serious disorders not suspected clinically.57 In contrast, it should be remembered that serious disease does not always show up immediately on a radiograph – about 30% of the osseous mass of a bone must be destroyed before a lesion is radiologically evident58 – so that too much reliance on radiographic appearances can give a false feeling of security. In the short term, it is wiser and safer to rely on the history and the clinical examination: if symptoms and signs warrant (i.e. warning signs are found), the patient should be assumed to have a serious disease and, rather than manipulative treatment being undertaken, specific tests should be performed.

A further deterrent in radiographic evaluation of the lumbar spine, and one that it is important to remember, is that it is the single largest source of gonadal irradiation.59 The total gonadal dose from a five-view lumbar spine examination is 75 millirads in men and 382 millirads in women60 – unnecessary61 oblique views are responsible for 65% of the irradiation dose.62 Hall63 estimated that the gonadal dose in women, when only a three-view examination is made, is equal to the dose of plain radiographs of the chest performed daily over a period of 6 years.

Radiographic ‘labels’ may confuse or bias patients and should never be transmitted to them as statements of disease because there is no evident correlation between radiographic appearances and the actual complaints. To patients, a statement such as ‘your back shows a marked degree of arthrosis’ means that they are incurable.64 It implies a back that is crumbling like mouldy cheese: the situation is definite, incurable and hopeless. The diagnosis of ‘osteoarthrosis’ condemns the sufferer, and many patients become deeply depressed when they hear that the back is ‘worn out’. An anxious or overconcerned patient will then suffer more from the idea that the back is beyond redemption and that no proper treatment for ‘osteoarthrosis’ exists, than he or she might from the back pain that is experienced. Technical investigation has become a problem rather than an aid. The radiograph does not help the patient; rather it may increase disability.65

Other imaging studies

Ever since 1921, attempts have been made to increase the contrast in imaging between the various structures in the spine. Initially, gas was introduced into the subarachnoid space.67 Next, positive contrast myelography with iodized oil solutions was begun in 1922.68 Gross toxic effects from this, including severe arachnoiditis and late meningeal disorders, led to the development of safer, water-soluble contrast agents.69

From the early 1940s, lumbar discs have been injected with contrast material in order to detect disc degenerations and disc ruptures.70 However, discography has always been controversial. In the past decade, several authorities have seriously questioned its use: it is painful, expensive and without diagnostic value71; the sensitivity, specificity and predictive value are not as good as in myelography, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)72; and the risk of post-discography discitis is high.73,74 Discographic studies are therefore considered obsolete.75,76

CT and MRI scans are highly sensitive but relatively unselective. In other words, these techniques have a very high prevalence of abnormal findings in images of asymptomatic individuals: postmortem studies show the existence of large, symptomless disc protrusions in almost 40% of cadavers77; myelograms in asymptomatic patients show defects in 37%78; and CT scans in subjects over 40 years of age show abnormality in more than 50%.79 Numerous MRI studies have also demonstrated the high incidence of disc degeneration in asymptomatic patients.80–86 Although additional imaging techniques are strongly indicated for the evaluation of patients presenting with warning symptoms and signs suggestive of neoplastic or infectious disorders, they have only limited value in the diagnosis of mechanical disorders of the lumbar spine.87 It cannot be stressed enough that excessive reliance on diagnostic studies without precise clinical correlation can lead to erroneous (and disastrous) treatment. Diagnosis of spinal disorders depends on a detailed history and physical examination, as does treatment. The increased tendency that has developed over recent years to recommend surgery in the presence of a positive CT scan is a major error. Given the high number of asymptomatic disc protrusions, many patients will go forward to an unnecessary operation. Boden puts it well when he states: ‘To get a MRI scan to see if there is anything wrong with the spine is usually the beginning of a very dangerous process.’88 The presence of a disc protrusion and its size are unimportant; it is the impact of the protrusion on the surrounding pain-sensitive structures that determines management. Imaging cannot usually distinguish symptomatic from asymptomatic disc herniation, since it is usually unable to detect the degree of inflammation, the degree of pain or the functional impact on a nerve. Clinical examination can do so, provided it is intelligently interpreted.

Electrodiagnosis

The use of electromyography (EMG) was introduced 50 years ago.89 Refinement of the technique, together with additional testing procedures (electrodiagnosis), now makes it possible to analyse and document nerve root dysfunction (level, degree and chronicity).90 Though it is the only laboratory study that directly assesses the physiological integrity of the roots, the test will not be helpful in patients with so-called non-compressive radiculopathy91: the protrusion compresses only the dural nerve root sleeve and not the fibres.

These factors mean that electrodiagnosis has very low specificity and sensitivity.92 This diagnostic technique is therefore not important in lumbar disorders, except when objective documentation of the physiological integrity of the lumbar roots is required, which is sometimes the case when there are medicolegal implications.

References

1. Korst v d, JK. Gewrichtsziekten. Utrecht: Bohn, Scheltema & Holkema; 1980.

2. MacNab, I. Backache. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1979.

3. Barbor R. Treatment for chronic low back pain. Proceedings of the IVth International Congress on Physical Medicine, Paris, 1964.

4. Shi, J, Jia, L, Yuan, W, et al, Clinical classification of cauda equina syndrome for proper treatment. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(3):391–395. ![]()

5. Gautschi, OP, Cadosch, D, Hildebrandt, G, Emergency scenario: cauda equina syndrome – assessment and management. Praxis (Bern 1994) 2008; 97:305–312. ![]()

6. Grundy, PF, Roberts, CJ, Does unequal leg length cause back pain? A case-control study. Lancet. 1984;2(8397):256–258. ![]()

7. Soukka, A, Alaranta, H, Tallroth, K, Heliövaara, M, Leg-length inequality in people of working age. The association between mild inequality and low-back pain is questionable. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991;16(4):429–431. ![]()

8. Cailliet, R. Low Back Pain Syndromes, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1975.

9. Meadows, JT. Orthopedic differential diagnosis in physical therapy: a case study approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1999.

10. Laslett, M, Aprill, CN, McDonald, B, Young, SB, Diagnosis of sacroiliac joint pain: validity of individual provocation tests and composites of tests. Man Ther. 2005;10(3):207–218. ![]()

11. Levin, U, Stenstrom, CH, Force and time recording for validating the sacroiliac distraction test. Clin Biomech 2003; 18:821–826. ![]()

12. Levin, U, Nilsson-Wikmar, L, Stenström, CH, Variability within and between evaluations of sacroiliac pain with the use of distraction testing. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(9):688–695. ![]()

13. Breig, A, Troup, JDG. Straight-leg raising. Spine. 1979; 4:242.

14. Dijck, P, Lumbar nerve root. The enigmatic eponyms. Spine. 1984;9(1):3–6. ![]()

15. De Buermann, W. Note sur un signe peu connu de la sciatique. Recherches expérimentales. Arch Physiol Norm Pathol. 1884; 16:375.

16. Fajersztajn, J. Über das gekreuzte Ischias Phänomen. Wien Klin Wehnschr. 1901; 14:41.

17. Smith, MJ, Wright, V, Sciatica and the intervertebral disc. J Bone Joint Surg 1958; 40A:1401. ![]()

18. Inman, VT, Sounders, JB. Clinico-anatomical aspects of lumbo-sacral region. Radiology. 1942; 38:669.

19. Falconer, MA, McGeorge, M, Begg, CA, Observations on the cause and mechanism of symptom production in sciatica and low back pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1948; 11:13–26. ![]()

20. Charnley, J, Orthopaedic signs in the diagnosis of disc protrusion. Lancet 1951; i:186–192. ![]()

21. Goddard, MD, Reid, JD, Movements induced by straight-leg raising in the lumbo-sacral roots. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1965; 28:12. ![]()

22. Ko, HY, Park, BK, Park, JH, et al, Intrathecal movement and tension of the lumbosacral roots induced by straight-leg raising. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85(3):222–227. ![]()

23. Jönsson, B, Strömqvist, B, The straight leg raising test and the severity of symptoms in lumbar disc herniation. A preoperative evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(1):27–30. ![]()

24. Summers, B, Malhan, K, Cassar-Pullicino, V, Low back pain on passive straight leg raising: the anterior theca as a source of pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(3):342–345. ![]()

25. Supic, MD, Broom, MJ, Sciatic tension signs and lumbar disc herniation. Spine 1994; 19:1066–1069. ![]()

26. Kosteljanetz, M, Bang, F, Schmidt-Olsen, S, The clinical significance of straight-leg raising (Lasègue’s sign) in the diagnosis of prolapsed lumbar disc. Spine. 1988;13(4):393–395. ![]()

27. Majlesi, J, Togay, H, Unalan, H, et al, The sensitivity and specificity of the Slump and the Straight Leg Raising tests in patients with lumbar disc herniation. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008;14(2):87–91. ![]()

28. Kapandji, IA. The Physiology of the Joints. vol 3, The Trunk and Vertebral Column. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1974.

29. Khuffash, B, Porter, RW, Cross leg pain and trunk list. Spine 1989; 14:602–603. ![]()

30. Cyriax, J. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine. vol I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Harcourt Brace & Co Ltd, Elsevier Health Science Books; 1982.

31. Edgar, MA, Park, WM, Induced pain patterns on passive straight-leg raising in lower lumbar disc protrusion. J Bone Joint Surg 1974; 56B:658. ![]()

32. Rothman, RH, Simeone, FA. The Spine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1988.

33. Pople, IK, Griffith, HB, Prediction of an extruded fragment in lumbar disc patients from clinical presentations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(2):156–158. ![]()

34. Vucetic, N, Svensson, O, Physical signs in lumbar disc hernia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996; 333:192–201. ![]()

35. Lew, PC, Morrow, CJ, Lew, AM, The effect of neck and leg flexion and their sequence on the lumbar spinal cord. Implications in low back pain and sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(21):2421–2424. ![]()

36. Reilly, BM. Practical Strategies in Outpatient Medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1984.

37. Gilbert, KK, Brismée, JM, Collins, DL, et al, 2006 Young Investigator Award Winner: lumbosacral nerve root displacement and strain: part 2. A comparison of 2 straight leg raise conditions in unembalmed cadavers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(14):1521–1525. ![]()

38. Lee, SH, Choi, SM. L1–2 disc herniations: clinical characteristics and surgical results. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2005; 38:196–201.

39. Estridge, MN, Rouhe, SA, Johnson, NG, et al, The femoral stretching test. A valuable sign in diagnosing upper lumbar disc herniation. J Neurosurg 1982; 57:813–817. ![]()

40. Calverly, JR, Mulder, DW, Femoral neuropathy. Neurology 1960; 10:963–967. ![]()

41. Cianci, PE, Piscatelli, RL, Femoral neuropathy secondary to retroperitoneal hemorrhage. JAMA 1969; 210:1100–1101. ![]()

42. Kreitz, BG, Cote, P, Young-Hing, K, et al, Crossed femoral stretching test. A case report. Spine 1996; 21:1584. ![]()

43. Morane, R, O’Connell, D, Walsh, MG, The diagnostic value of facet joint injections. Spine 1988; 13:1407–1410. ![]()

44. Dory, M, Arthrography of the lumbar facet joints. Radiology 1981; 140:23–27. ![]()

45. Frymoyer, JW, Newberg, A, Pope, MH, et al, Spine radiographs in patients with low back pain. J Bone Joint Surg 1984; 66A:1048–1055. ![]()

46. Sanders, HWA, et al, Klinische betekenis van degeneratieve afwijkingen van de lumbale wervelkolom en consequenties van het aantonen ervan. Tijdschr Geneeskd 1983; 127:1374–1385. ![]()

47. Park, WM. The place of radiology in the investigation of low back pain. Clin Rheum Dis. 1980; 6:93–132.

48. Splithoff, CA, Lumbosacral junction: röntgenographic comparison of patients with and without backache. JAMA 1953; 152:1610–1613. ![]()

49. Fullenlove, TM, Williams, AJ, Comparative röntgen findings in symptomatic and asymptomatic backs. JAMA 1957; 168:572–574. ![]()

50. La Rocca, H, MacNab, I, Value of pre-employment radiographic assessment of the lumbar spine. Can Med Assoc J 1969; 101:383–388. ![]()

51. Wiltse, LL, The effect of the common anomalies of the lumbar spine upon disc degeneration and low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am 1971; 2:569–582. ![]()

52. Magora, A, Schwartz, A. Relation between the low back pain syndrome and X-ray findings. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1976; 8:115–125.

53. Torgeson, WD, Dotler, WE, Comparative röntgenographic study of the asymptomatic and symptomatic lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg 1976; 58A:850–853. ![]()

54. Wiesel, SW, Bernini, P, Rothman, RH. The aging lumbar spine. In: Diagnostic Studies in Evaluating Disease and Aging in the Lumbar Spine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1982.

55. Dabbs, VM, Dabbs, LG, Correlation between disc height narrowing and low-back pain. Spine 1990; 15:1366–1369. ![]()

56. Van Tulder, MW, Assendelft, WJJ, Koes, B, Bouter, LM, Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain; a systematic review of observational studies. Spine 1997; 22:427–434. ![]()

57. Brolin, I. Product control of lumbar radiographs. Läkartidningen. 1975; 72:1793–1795.

58. Edelstyn, GA, Gillespie, PG, Grebbel, FS, The radiological demonstration of skeletal metastases: experimental observations. Clin Radiol 1967; 18:158. ![]()

59. Liang, HM, Katz, JN, Frymoyer, JW. Plain radiographs in evaluating the spine. In: Frymoyer JW, ed. The Adult Spine. New York: Raven Press; 1991:302.

60. Shaigetoshi, A, Russell, W, Dose to active bone marrow, gonads and skin from röntgenography and fluoroscopy. Radiology 1971; 101:669–678. ![]()

61. Rhea, JT, DeLuca, SA, Llewellyn, HJ, Boyd, RJ, The oblique view: an unnecessary component of the initial adult lumbar spine examination. Radiology 1980; 134:45–47. ![]()

62. Scavone, JG, Latshaw, RF, Weidner, WA, Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs: an adequate lumbar spine examination. AJR 1981; 136:715–717. ![]()

63. Hall, FM, Overutilization of radiological examinations. Radiology 1976; 120:443–448. ![]()

64. Rockey, PH, Tompkins, RK, Wood, RW, Wolcott, BW, The usefulness of X-ray examinations in the evaluation of patients with back pain. J Fam Pract 1978; 7:455–465. ![]()

65. Van den Bosch, MA, Hollingworth, W, Kinmonth, AL, Dixon, AK, Evidence against the use of lumbar spine radiography for low back pain. Clin Radiol 2004; 59:69–76. ![]()

66. Liang, M, Komaroff, AL, Röntgenograms in primary care patients with acute low back pain: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Intern Med 1982; 142:1108–1112. ![]()

67. Jacobaeus, HC. On insufflation of air into the spinal canal for diagnostic purposes in cases of tumors in the spinal canal. Acta Med Scand. 1921; 55:555–564.

68. Siccard, JA, Forrestier, JE. Méthode générale d’exploration radiologique par l’huile iodée (Lipiodol). Bull Mem Soc Med Hop Paris. 1922; 46:463–469.

69. Grainger, RG, Gumpert, J, Sharpe, DM, Carson, J, Water soluble lumbar radiculography: a clinical trial of Dimer-X, a new contrast medium. Clin Radiol 1971; 22:57–62. ![]()

70. Lindblom, K. Protrusions of the discs and nerve root compression in the lumbar region. Acta Radiol Scand. 1944; 25:195–212.

71. Holt Jr, EP, The question of lumbar discography. J Bone Joint Surg 1968; 50A:720–726. ![]()

72. Gibson, MJ, Buckley, J, Mawhinney, R, Magnetic resonance imaging and discography in the diagnosis of disc degeneration: a comparative study of 50 discs. J Bone Joint Surg 1968; 68B:369–373. ![]()

73. Fraser, RD, Osti, OL, Vernon Roberts, B, Discitis after discography. J Bone Joint Surg 1987; 69B:31–35. ![]()

74. Sachs, BL, Vanharanta, H, Spivery, MA, Dallas discogram description: a new classification of CT/discography in low back disorders. Spine 1987; 12:287–294. ![]()

75. Shapiro, R, Lumbar discography: an outdated procedure. J Neurosurg 1986; 64:686–691. ![]()

76. Nachemson, A, Lumbar discography – where are we today? Spine 1989; 14:555–557. ![]()

77. MacRae, DL, Asymptomatic intervertebral disc protrusion. Acta Radiol 1956; 46:9. ![]()

78. Hitselberger, WE, Whitten, RM, Abnormal myelograms in asymptomatic patients. J Neurosurg 1968; 28:204. ![]()

79. Wiesel, SW, Tsourmas, N, Feffer, HL, et al, A study of computer-assisted tomography: 1. The incidence of positive CAT scans in an asymptomatic group of patients. Spine 1984; 9:549–551. ![]()

80. Powell, MC, Wilson, M, Szypryt, P, Symonds, EM, Prevalence of lumbar disc degeneration observed by magnetic resonance in symptomless women. Lancet 1986; Dec 13:1366–1367. ![]()

81. Weinreb, JC, Wolbarsht, LB, Cohen, JM, et al, Prevalence of lumbosacral intervertebral disc abnormalities on MR images in pregnant and asymptomatic non-pregnant women. Radiology 1989; 170:125–128. ![]()

82. Boden, SD, Davis, DO, Dina, TS, et al, Abnormal magnetic resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg 1990; 72A:403–408. ![]()

83. Buirski, G, Silberstein, M, The symptomatic lumbar disc in patients with low-back pain. Magnetic resonance imaging appearances in both a symptomatic and control population. Spine 1993; 18:1808–1811. ![]()

84. Jensen, MC, Brant-Zawadzki, MN, Obuchowski, N, Modic, MT, Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med 1994; 331:69–73. ![]()

85. Ong, A, Anderson, J, Roche, J, A pilot study of the prevalence of lumbar disc degeneration in elite athletes with lower back pain at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37(3):263–266. ![]()

86. Stadnik, TW, Lee, RR, Coen, HL, et al, Annular tears and disk herniation: prevalence and contrast enhancement on MR images in the absence of low back pain or sciatica. Neuroradiology 1998; 206:49–55. ![]()

87. Frymoyer, JF, Gordon, S. New Perspectives in Low Back Pain. Am Acad Orthop Surg, Park Ridge. 1988; 45–47.

88. Boden, SD, The use of radiographic imaging studies in the evaluation of patients who have degenerative disorders of the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg 1996; 78A:114–124. ![]()

89. Shea, PA, Woods, WW, Werden, DH, Electromyography in diagnosis of nerve root compression syndrome. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 1950; 64:93–104. ![]()

90. Glantz, RH, Haldemann, S. Electrodiagnosis. In: Frymoyer JW, ed. The Adult Spine. New York: Raven Press; 1991:541–548.

91. Wilbourn, AJ, Aminoff, MJ, AAEE Minimonograph 32: the electrophysiologic examination in patients with radiculopathies. Muscle Nerve 1988; 11:1099–1114. ![]()

92. Hudgins, WR, Computer-aided diagnosis of lumbar disc herniation. Spine 1983; 8:604–615. ![]()