Clinical examination of the knee

History

Knee problems are always difficult to evaluate and every possible assistance is needed to make a proper diagnosis. A chronological history, as summarized in Box 50.1, is therefore the first, and sometimes even the most important, element. Cyriax used to say that one who ‘doesn’t have a diagnosis after the history, will hardly get one after the clinical examination’.

The patient should be questioned about occupation and sporting activities.

• Locking: sudden (painful) limitation occurs during a movement, whereas other movements are free and painless. The knee can be locked in flexion (extension being limited) or extension (flexion being impossible).

• Twinge: a sudden, sharp and unexpected pain is felt. For example, the patient feels abrupt, unforeseen and sharp pain at the inner side of the knee during walking. The pain disappears immediately and normal walking again becomes possible.

• Feeling of giving way: this is the typical sensation in instability – a sudden feeling of weakness. It feels as if the knee cannot bear the body weight during a particular movement. The knee tends to ‘collapse’.

Onset

• When did it start? Is this an acute, subacute or chronic problem?

• How did it start? Did the pain come on for no apparent reason or was there an injury?

If there was trauma

Describe the immediate symptoms:

• Where was the initial pain? At one side, all over or inside the joint?

• Was there any swelling? Immediately or after some time? An immediate effusion is always haemorrhagic and therefore indicates a serious lesion. If a swelling appears after some time, it is the consequence of a synovial reaction.

• Did the knee give way? Immediately or after some time?

• Was there any locking? If so, was the knee locked in flexion (which is typical for meniscal lesions) or was it in extension (as in impacted loose bodies from osteochondritis dissecans)? How did the knee become unlocked? By manipulation (meniscus) or spontaneously (loose body)?

Evolution

• Did the pain change from one side of the joint to the other or did the pain spread? Pain moving from one side of the joint to another is characteristic of a loose body: the localization of the pain travels with the impacted loose fragment.

• What was the evolution of the swelling?

• For how long were you disabled?

• What treatment did you have and to what effect?

• Have there been any recurrences? If so, what brought them on and how did they progress?

Current symptoms

Finally, the current complaint is discussed.

• Describe the exact localization.

• Do you have nocturnal pain or morning stiffness? Pain at night usually indicates a high degree of inflammation. It occurs in acute ligamentous lesions, haemarthrosis and arthritis. Long-standing morning stiffness is usually an indication of rheumatic inflammation.

• What is the effect of going upstairs and downstairs, and which is the more troublesome? Going downstairs loads not only the extensor mechanism but also the posterior cruciate ligament and the popliteus tendon. Going downstairs is also very painful in impacted loose bodies.

• Do you have twinges? Very often, a twinge means an impacted loose body or a meniscus.

• Does the knee give way? Does it actually give way or just feel as though it might?

At the end of history taking, patients must be asked about their general state of health.

Inspection

In the sitting position

The most important observations of the patellar position are made with the patient seated on the examination table, the legs hanging free and the knees flexed to 90°. The examiner first assesses the patellar position and the position of the tibial tuberosity and patellar ligament by viewing the knee from the lateral aspect. Thereafter the examiner views the knees from the anterior aspect while the patient holds both knees together. Normally positioned patellae face straight ahead. Malalignment of the kneecap is seen as a patella ‘looking’ up and over the shoulders of the examiner (see p. 722).

Functional examination

The routine clinical examination of the knee consists of 10 passive movements, two for the joint and eight for the ligaments, and two resisted movements (Table 50.1). If signs warrant, or if suspicion of meniscal lesions or instability arises from the history, complementary tests can be performed.

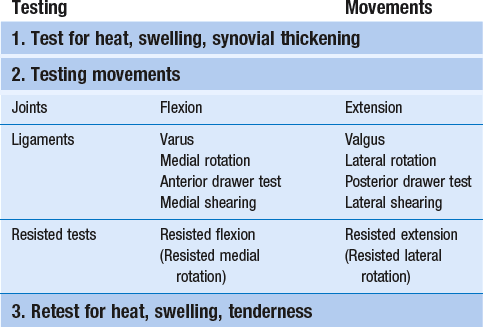

Two primary movements for the joint

As in the elbow, the range of rotation becomes restricted only in advanced arthritis. Therefore extension and flexion (Fig. 50.1) are the two movements used to test the mobility of the joint.

Eight secondary movements for the ligaments

Stretching the ligaments tests them for pain and laxity.

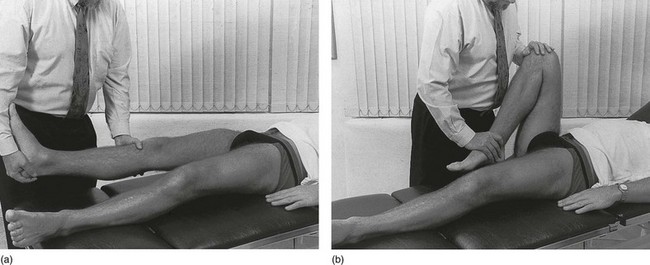

Valgus strain

Strong valgus movement applied with counterpressure at the lateral femoral condyle tests the medial collateral ligament (Fig. 50.2a). Normally, this is done in full extension. In a minor sprain or in a minor degree of instability resulting from previous overstretching, pain and laxity are probably better disclosed if the test is repeated in slight flexion (30°).

Fig 50.2 Valgus (a) and varus (b) movement.

Varus strain

Strong varus movement is applied during counterpressure at the medial femoral condyle and tests the lateral collateral ligament (Fig. 50.2b). Again, the test can be repeated in slight flexion (30°).

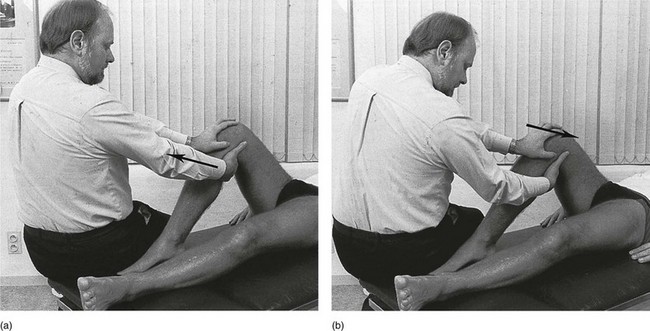

Lateral rotation

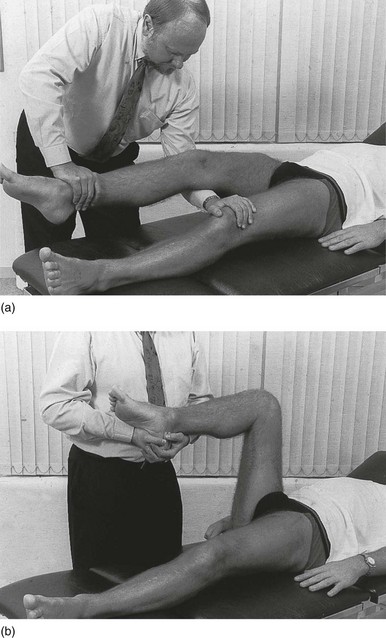

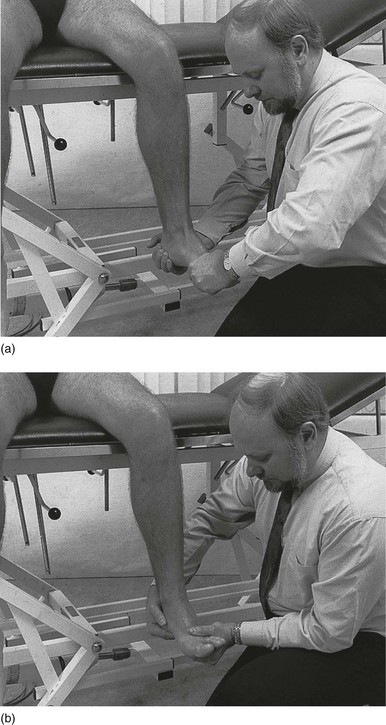

Lateral rotation of the knee puts stress on the medial coronary ligament and the posterior fibres of the medial collateral ligament. The knee is flexed to a right angle and the heel rests on the couch. To prevent rotation in the hip, the examiner places the contralateral shoulder against the knee, the arm under the lower leg and a hand under the heel. The other hand is placed at the inner side of the foot, which is pressed upwards in dorsiflexion. Lateral rotation is now easily performed by using the foot as a lever (Fig. 50.3a). The normal end-feel is elastic.

Fig 50.3 Lateral (a) and medial (b) rotation.

Medial rotation

Medial rotation puts stress on the lateral coronary ligament and the anterior cruciate ligament. The hip and knee are flexed to right angles. The lower leg is supported by the contralateral forearm of the examiner. The hands are clasped tightly about the patient’s heel, which is forced into dorsiflexion. With a combined movement of both wrists, the leg is turned into medial rotation (Fig. 50.3b). In order to protect the lateral ligaments of the ankle, it is important to exert pressure at the ankle and not beyond the calcaneocuboid joint line. The normal end-feel is elastic.

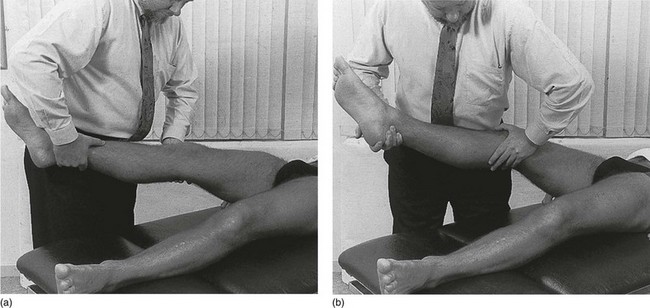

Anterior drawer test

The knee is flexed to a right angle, and the examiner sits on the patient’s foot and places one hand on the patella. The other hand is placed at the back of the upper tibia, which is drawn forwards with a strong jerk to test for pain if the anterior cruciate ligament is damaged (Fig. 50.4a). The anterior drawer test in 30° of flexion (‘Lachman’s test’) seems to be more precise in disclosing elongation or rupture in the anterior cruciate ligament (see Ch. 53).

Posterior drawer test

The examiner once again sits on the patient’s foot. One hand is placed on the tibial tuberosity, while the other rests at the back of the knee. A strong backward jerk is exerted on the tibia to test the integrity of the posterior cruciate ligament (Fig. 50.4b). In a normal joint, no movement takes place and the test is completely painless.

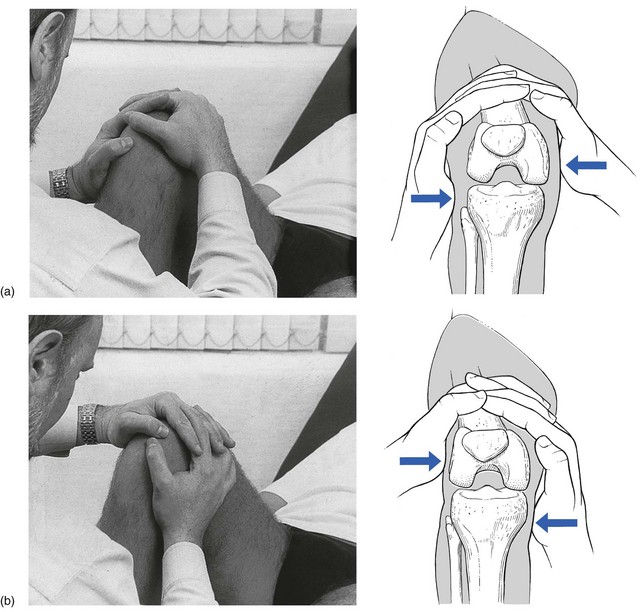

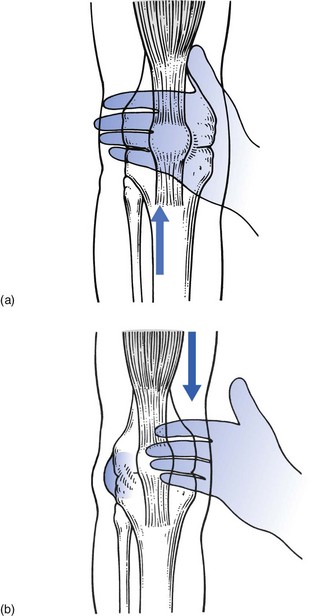

Medial shearing strain

The knee is held at a right angle. The examiner sits opposite the patient, interlocks the fingers and places the heel of one hand at the lateral tibial condyle, with the heel of the other hand at the medial femoral condyle. By applying a strong shearing strain, an attempt is made to move the tibia medially on the femur (Fig. 50.5a). Pain may be elicited when a loose body is present. In a tear of the lateral meniscus, this manœuvre can displace part of the meniscus to the other side of the femoral condyle. A loud click is then heard and the full range of passive extension is immediately lost.

Lateral shearing strain

This action is the reverse of medial shearing strain. The heel of one hand is placed on the lateral femoral condyle and the heel of the other on the medial tibial condyle (Fig. 50.5b). A strong shearing force moves the tibia laterally on the femur and may provoke a click when a loose body or a longitudinal tear of the medial meniscus is present. It also elicits pain when a strain of the posterior cruciate ligament is present.

Two resisted movements for the contractile structures

Resisted extension

The knee is kept slightly bent. The examiner places one arm under the patient’s knee. The other hand is placed on the distal end of the tibia, where it resists extension by the patient (Fig. 50.6a). Pain and weakness are noted. If there is any pain, a lesion of the quadriceps mechanism is likely. If there is any weakness, a lesion of the nerve supply, usually the third lumbar nerve root, is present. Pain and weakness occur in a fractured patella or after a major rupture of the muscle belly.

Palpation

Palpation for warmth and fluid in the stationary joint is done before the clinical examination, and palpation for synovial thickening, tenderness, warmth and irregularities is done after the clinical examination. Finally, crepitus is sought during movement (Box 50.2).

Fluid

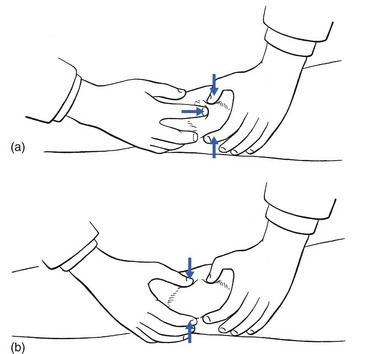

Patellar tap

This is the classic test. Manual pressure empties the suprapatellar pouch and moves the fluid under the patella. In the meantime, the thumb and middle finger of the other hand are used to press on the medial and lateral recesses until they empty. Any fluid now lies between the patella and femur. Next the index finger of the lower hand pushes the patella downwards (Fig. 50.7a). If fluid is present, the patella is felt to move. When it strikes the femur, a palpable tap is felt, followed by an immediate upward movement. This is the sensation of an ice-cube pushed downwards in a glass of water: although the patella moves downwards, the pressure of the fluid immediately shifts the bone upwards against the palpating finger. In a normal knee, the patellar tap is not elicited.

Eliciting fluctuation

The examiner’s thumb and index finger are placed at each side of the patient’s knee, just beyond the patella. With the interdigital web I–II of the other hand, the examiner squeezes the suprapatellar pouch, pushing all the fluid downwards under the patella, which forces the two fingers of the palpating hand apart (Fig. 50.7b). This sensitive test will detect even very small volumes of fluid and enables an experienced examiner to differentiate between blood and clear fluid. Blood fluctuates en bloc, like a mass of jelly, whereas a clear effusion flows like water.

Visual testing by eliciting fluctuation

This test is not strictly palpation but relies on vision. Stroking in a sweeping motion with the back of the hand over the lateral recess and the suprapatellar pouch moves the fluid upwards and medially (Fig. 50.8a). In a minor effusion, all the fluid is moved to the medial part of the suprapatellar pouch. The lateral recess is then empty and can be seen as a groove between patella and lateral femoral condyle. Sweeping with the back of the hand over the suprapatellar pouch and downwards over the medial recess will now transfer the fluid laterally (Fig. 50.8b), where a small prominence appears. This is the most delicate test for effusion in the knee joint and demonstrates as little as 2 or 3 mL of fluid.

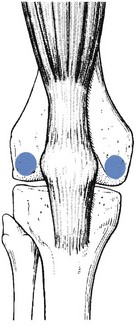

Synovial thickening

Synovial swelling is best detected at the medial and lateral condyles of the femur, about 2 cm posterior to the medial and lateral edges of the patella (Fig. 50.9). Here the synovium lies almost superficially, covered only by skin and subcutaneous fat. It is palpated by rolling the structures between fingertip and bone. Normally nothing except skin can be felt. In synovial thickening, a dense structure can be felt.

Accessory tests

These tests, summarized in Box 50.3, are performed only if the history or clinical examination warrants them. Meniscus tests are thus performed when the history includes periods of locking.

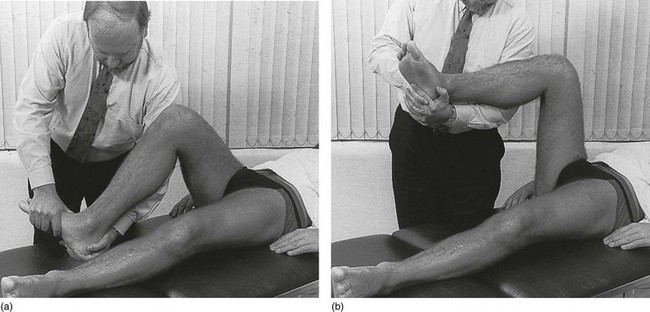

Resisted internal and external rotation

The patient sits on the table, the knee flexed to a right angle and the legs hanging over the edge. The examiner holds the foot in dorsiflexion and asks the patient to press outwards and inwards, meanwhile maintaining the neutral position with both hands. Internal (medial) rotation tests the medial hamstrings and popliteus (Fig. 50.10a). External (lateral) rotation tests the biceps femoris and the upper tibiofibular joint (Fig. 50.10b).