Clinical examination of the hip and buttock

Introduction

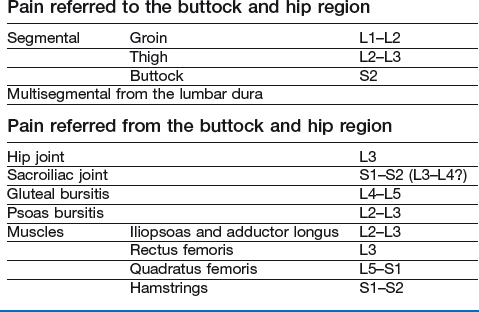

Pain felt in the hip and buttock does not necessarily originate from a lesion in these areas. Cyriax stated that most pain in the buttock derived from the lumbar spine (reference from L1 and S2), whereas pain in the thigh is referred from the lumbar spine and hip region as often as it has a local origin. When dealing with pain in this area, it is often not easy at first to determine if there is a problem in the lower back, the sacroiliac joint or the hip. Therefore, a detailed and chronologically ordered history is first taken, as described for the lumbar spine (see Ch. 36). Past and present symptoms are noted and the examiner is informed about the exact site and nature of the pain. Next, a preliminary examination must be performed that includes the whole lower quadrant: from the lumbar spine, over the sacroiliac and hip joints to the upper leg. Once it is clear that the symptoms do not arise from the lumbar spine or sacroiliac joint, the structures of the hip are examined more intensively.

Referred pain

Pain referred to the buttock and hip region

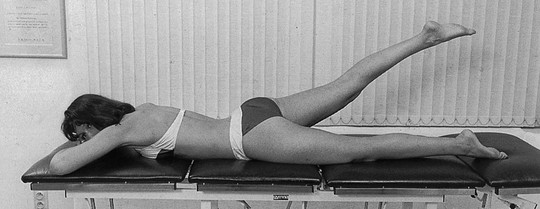

The first lumbar dermatome is represented by an area of skin at the outer and upper buttock which is partly overlapped by the second and third lumbar dermatomes (Fig. 45.1).

Fig 45.1 Dermatomes at the hip and buttock.

The skin of the lower part of the buttock is derived from the first and second sacral segments. The fourth and fifth lumbar segments are not present in the buttock. In spite of this, fourth and fifth lumbar disc protrusions are the commonest cause of pain in the buttock,1 and are an expression of dural pain.

Pain referred from the buttock and hip region

Hip joint

The hip joint is formed largely from the third lumbar segment. Therefore pain referred from the joint may be felt in the upper and inner part of the buttock, and the inner aspect and front of the thigh and leg as far as the medial malleolus. Rarely, the joint has developed mainly from the fourth lumbar segment. In such cases, pain spreads along the outer side of the mid-thigh and leg, and may reach the big toe. Because referred pain does not always occupy the whole dermatome, it is possible for a hip lesion to refer pain to the knee only, perhaps also spreading along the front of the tibia.1,2 But pain felt only at the upper inner quadrant of the buttock strongly points to the low back or the sacroiliac joint.

Sacroiliac joint

The sacroiliac joint normally gives rise to pain along the back of the thigh and calf. In rare instances, pain is felt in the groin as well (see p. 598).

History

History taking is largely the same as in lumbar spine disorders (see Ch. 36) because it is not always clear from the onset if the patient has a lumbar, sacroiliac or hip problem. However, once it has become more or less apparent that the complaints are the outcome of a hip lesion, some particular questions should be asked.

After the usual questions on the patient’s age, sex, occupation and hobbies, the examiner tries to find out what the actual problem is: pain, functional disability or instability? The problem should then be worked out systematically via a chronological approach: when and how did the problem start, what was its evolution and what are the current symptoms (Box 45.2)?

Onset

• When did it start? Is it an acute, subacute or chronic problem?

• What brought it on or how did it start? Was there an injury or did the pain appear without obvious reason?

Current symptoms

• What is the problem now? The examiner makes further enquiries about pain, pins and needles, instability or functional disability.

• Where do you feel the pain (which dermatome)? As exact a description as possible must be obtained.

• Do you have pain at rest or during the night? Nocturnal pain indicates a high degree of inflammation and may point to a serious disorder such as arthritis, haemarthrosis, tumour, metastasis or fracture. However, in an ordinary gluteal bursitis, lying on the affected side at night is also often painful.

• What brings the pain on? Sitting, standing up, walking and running, climbing stairs, sitting or lying? If the pain starts after walking a certain distance, ask if it disappears after standing still for a while and reappears after walking the same distance: this suggests claudication in the buttock.

• Does a particular movement provoke the pain?

• Does the pain appear at the beginning, during or after some sort of exertion?

• Do you have twinges, and when? This symptom is defined as a sudden, sharp and unexpected pain and is clearly indicative of momentary subluxation of a loose body. On walking, a severe twinge is felt shooting down the front of the thigh and the leg gives way at this point.

• Is any movement accompanied by a click? Clicking may be indicative of loose bodies or acetabular labrum tears.3,4

• Does coughing hurt? This dural sign is highly suggestive of a lumbar intervertebral disc lesion but is also found in sacroiliac arthritis.

• Do you have a feeling of instability? Any disorder altering the anatomical relations in the hip region – for example, congenital dislocation, coxa vara or epiphysiolysis – may lead to instability. Painful conditions at the hip and neurological disorders, such as paresis of the fifth lumbar root involving the gluteus medius, or of the third lumbar root involving the quadriceps, are other possibilities.

• Do you have any functional disability? This may be stiffness on standing up or starting to walk, or inability to put on shoes. All these direct attention to an arthrotic joint.

• Do you have symptoms in other parts of the body? The possibility of systemic disease arises: for example, rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis.

Inspection

Posture

Next, posture is assessed, especially in relation to the lower back, pelvis and lower extremities. Details of observing the patient’s posture are dealt with in the chapter on the lumbar spine (see p. 498).

Hip joint position

The position of the hip joint can be informative about a pathological condition. In acute arthritis and gross osteoarthrosis, the hip joint is often in flexion, which is compensated for by an anterior tilt of the pelvis together with increased lordosis of the lumbar spine. The femur is also slightly abducted and laterally rotated. This in turn influences the position of the knee and foot, which are also rotated. It is important to remember, however, that excessive external rotation of the leg, with ‘toeing out’, also occurs in external femoral neck retroversion or a slipped upper femoral epiphysis and in pelvic torsion. Posterior rotation of the innominate bone may also be responsible for slight external rotation of the leg. In contrast, ‘toeing in’ may be the result of extreme femoral neck anteversion.5

In third lumbar root pain, patients may also adopt a flexed position to relax the nerve root.

Functional examination

Preliminary examination

Before starting the clinical examination of the buttock and hip, a preliminary examination of the lumbar spine and sacroiliac joint (summarized in Box 45.4) should be performed to confirm the absence of a lesion in these regions (see Ch. 36).

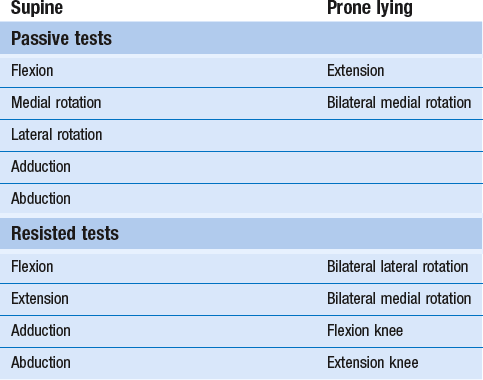

Basic functional examination

Routine clinical examination consists of 15 functional tests (Table 45.1). If signs warrant or the history is indicative, complementary tests can be performed.

Supine

Passive movements

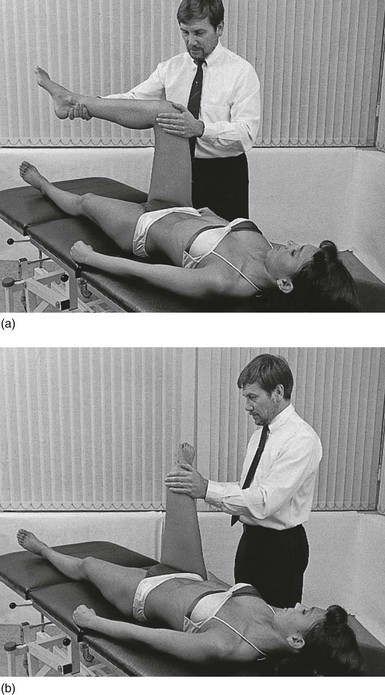

Passive flexion

The anterior thigh is moved upwards until it touches the abdomen (Fig. 45.2). The average range of movement is 140°, with a soft end-feel caused by tissue approximation. It is important to remember that the last 30° of this apparent hip movement is carried out by the pelvis, which flexes at the lumbar joints. This backward tilt of the pelvis also moves the other thigh towards extension, and when there is a restriction of extension in the contralateral hip joint, the thigh will move upward (Thomas’s sign of flexion contracture of the hip).6

Fig 45.2 Passive flexion.

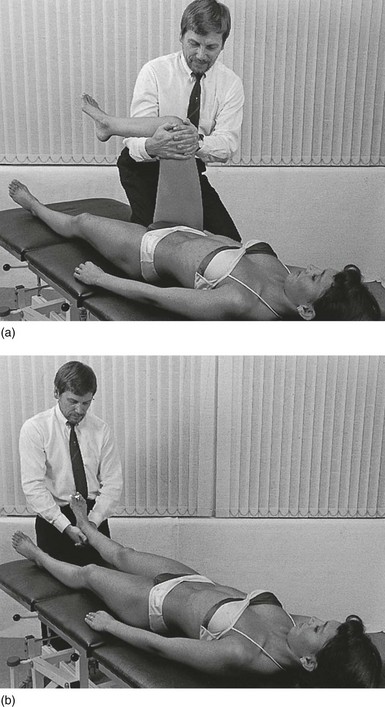

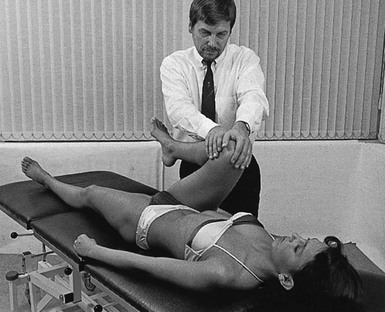

Passive rotations

The hip and knee are bent to 90° in order to examine rotation movements (Fig. 45.3). The contralateral hand is used to stabilize the femur at the knee, while the other hand, placed at the distal end of the lower leg, performs medial and lateral rotation movements. At the end of range, a capsular elastic end-feel should be found. The average range of passive lateral rotation is 60°, and that of medial rotation is 45°. In advanced arthrosis or arthritis, the end-feel is hard. However, a soft end-feel replaces a hard one when swift erosion of the femoral head occurs in arthrosis.

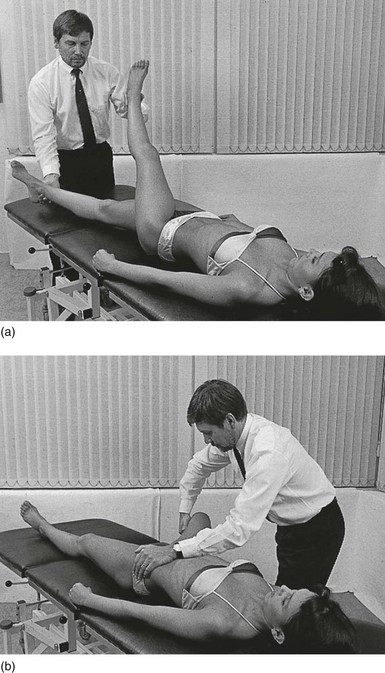

Passive adduction

This is tested after raising the other leg, so as to get it out of the way (Fig. 45.4a). The range of movement is 30° on average. In a normal joint, the end-feel is elastic, caused by stretching of the capsule and muscles that lie on the outer side of the hip. When movement is painful at the outer side of the hip, a lesion of the iliotibial tract1 should be considered. If some resisted movements are also painful, gluteal bursitis is probably the cause.

Passive abduction

The ipsilateral hand is placed at the medial and dorsal side of the thigh, as far distal as possible. The knee is put into 90° flexion, which eliminates the influence on the movement of the biarticular part of the adductors, i.e. the semitendinosus, semimembranosus and gracilis. The other hand stabilizes the pelvis (Fig. 45.4b).

Resisted movements

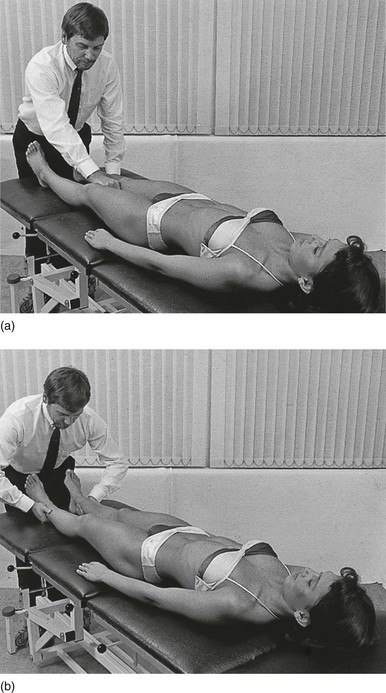

Resisted flexion

This is performed with the hip joint flexed to 90°. Both hands are placed at the anterior and distal end of the thigh so as to exert counterpressure, while the patient attempts to flex the hip. The lower leg is supported in 90° of flexion at the knee. To stabilize the ilium, the examiner places one knee against the tuberosity of the ischium (Fig. 45.5a). Pain and weakness are noted and again carefully compared with the other hip. This test gives a positive result in the following circumstances:

• If pain alone is provoked, the possible lesions are: strain in the psoas, sartorius or rectus femoris muscle; obturator hernia is another possibility.

• Painful weakness is found in avulsion fracture of the lesser trochanter, abdominal neoplasm infiltrating the psoas muscle or metastasis in the upper femur.

• Painless weakness is the result of paresis of the psoas muscle, usually the consequence of a second lumbar root palsy but rarely a third. If the palsy is bilateral, neoplasm at the second lumbar level should always be suspected.

Resisted extension

This tests the gluteus maximus and the hamstrings. The hip joint is slightly flexed and the knee joint remains extended. The examiner places both hands at the heel of the foot and resists extension (Fig. 45.5b).

Resisted adduction

The examiner places the clenched fist between the patient’s knees and asks the patient to squeeze (Fig. 45.6a).

• Pain is usually the result of an adductor longus lesion.7 Fracture, neoplastic invasion of the pubic bone and a sacroiliac lesion are other possibilities.

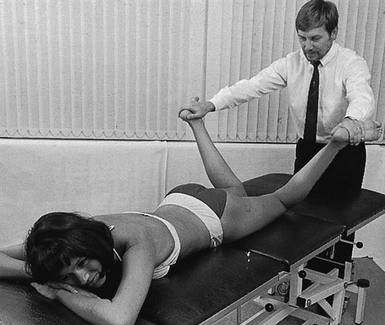

Resisted abduction

The hip joints are placed in a slightly abducted position. The examiner resists the abduction movement at the ankles (Fig. 45.6b). This test primarily activates the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus and tensor fasciae latae.

• Pain is usually the result of the compression of underlying structures, such as an inflamed gluteal bursa, or is the consequence of stress placed on strained or inflamed sacroiliac ligaments.

• Weakness is found in a palsy of the fifth lumbar root from a disc herniation at the same level. It may also be the result of anatomical changes, as in congenital dislocation of the hip or coxa vara; in such circumstances the muscle’s origin lies closer to its insertion, which makes the contraction less efficient.

Prone

Passive movements

There are two passive movements.

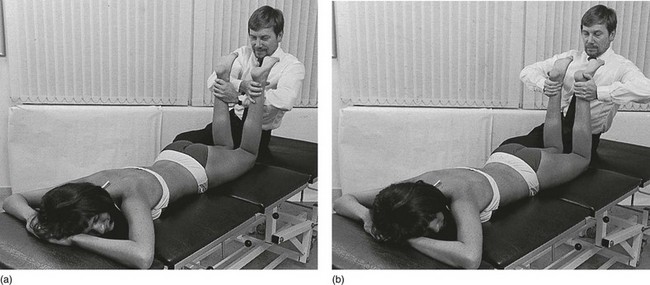

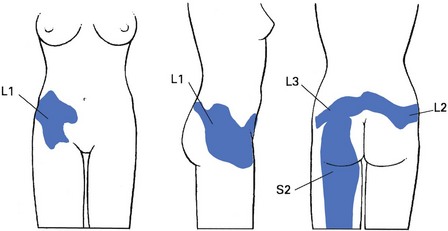

Passive extension

The ipsilateral hand is placed over the mid-buttock. The other hand grasps the thigh just below the patella. The test is performed by simultaneous movement of both hands in opposite directions. The knee should stay extended, to prevent tension on the rectus femoris. By pressing the pelvis firmly on to the couch, the examiner prevents any stress from reaching the sacroiliac and the lumbar joints (Fig. 45.7). The average range of movement is 30°. The normal end-feel is capsular-elastic. Extension is one of the movements that become restricted in arthritis or arthrosis.

Fig 45.7 Passive extension.

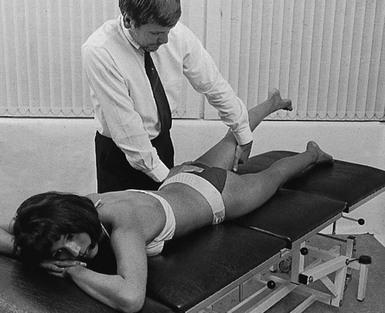

Passive medial rotation

Both hips are examined together, even though a separate assessment will have been made in the supine position. The knees are flexed to a right angle. The thighs are rotated by pressing the feet apart (Fig. 45.8). Care should be taken to ensure that the buttocks are level.

Fig 45.8 Passive medial rotation.

A small amount of limitation of medial rotation can now be ascertained.

Resisted movements

There are four resisted movements.

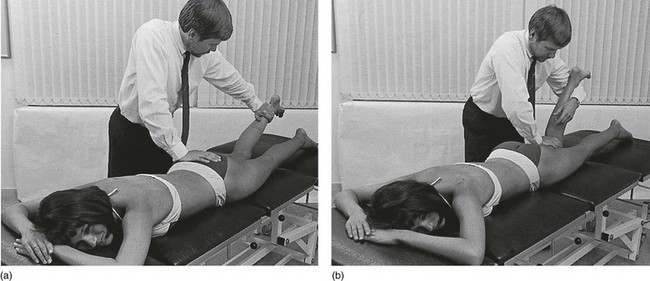

Bilateral resisted lateral rotation

This is performed with the knees flexed to a right angle. With crossed arms, the examiner presses the hands against the inner side of both the patient’s legs at the internal malleoli of the ankle (Fig. 45.9a).

Bilateral resisted medial rotation

This is performed in the same way but both hands are pressed against the outer malleoli (Fig. 45.9b). This creates tension in the medial part of the hamstrings, tensor fasciae latae and gluteus medius and minimus. However, pain is more often the result of compression of an inflamed bursa.

Resisted flexion of the knee

This tests the hamstrings. The knee is positioned in 70° of flexion. One hand fixes the ilium, while the other hand presses against the distal end of the lower leg (Fig. 45.10a).

• Pain in the thigh results from a lesion in the semitendinosus, semimembranosus or biceps femoris. Pain at the ischial tuberosity indicates tendinitis of one of these muscles or a lesion of the sacrotuberous ligament.

• Weakness is present in first and second sacral root palsy and is usually the result of disc herniation at the fifth lumbar level.

Resisted extension of the knee

This tests the quadriceps. The knee is held in 70° of flexion. The ipsilateral hand is used to stabilize the thigh on the couch. The elbow of the other arm is placed at the distal end of the lower leg to resist extension movement (Fig. 45.10b). In order to be able to withstand even the strongest extension, the hand of this arm may grasp the stabilizing arm.

Accessory tests

If signs warrant or the history is indicative, accessory tests can be performed.

Technical investigations

This is especially the case in:

Two diagnostic techniques have become popular during recent decades. Ultrasonography (ultrasound) is an excellent method to detect intra-articular fluid.8,9 It may also be a very useful auxiliary method in estimating the degree of tendon and muscle ruptures10 and in localizing bursitis.11 However, the method requires a lot of experience, and diagnostic precision depends entirely on the skill of the examiner.

There is general agreement that hip arthroscopy is valuable as a diagnostic investigation in patients with catching or transient locking of the hip (loose bodies, synovial tags and lesions of the labrum).12–14

Examination of the hip and buttock is summarized in Box 45.4.

References

1. Cyriax, J. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine; vol. I. Baillière Tindall, London, 1982.

2. Adams, JC, Hamblen, D. Outline of Orthopaedics, 12th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

3. Fitzgerald, R. Acetabular labral tears. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1995; 311:60–68.

4. Freehill, MT, Safran, MR, The labrum of the hip: diagnosis and rationale for surgical correction. Clin Sports Med. 2011;30(2):293–315. ![]()

5. Hoppenfeld, S. Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1976.

6. Lee, KM, Chung, CY, Kwon, DG, et al, Reliability of physical examination in the measurement of hip flexion contracture and correlation with gait parameters in cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(2):150–158. ![]()

7. Renström, P, Peterson, L, Groin injuries in athletes. Br J Sports Med 1980; 21:30. ![]()

8. Marchal, GJ, Van Holsbeeck, MT, Raes, M, et al, Transient synovitis of the hip in children: role of US. Radiology 1987; 162:825–828. ![]()

9. Moss, SG, Schweitzer, ME, Jacobson, JA, et al, Hip joint fluid: detection and distribution at MR imaging and US with cadaveric correlating. Radiology 1998; 208:43–48. ![]()

10. Fornage, BD. Ultrasonography of Muscles and Tendons. New York: Springer; 1988.

11. Flanagan, FL, Sant, S, Coughlan, RJ, O’Connell, D, Symptomatic enlarged iliopsoas bursae in the presence of a normal plain hip radiograph. Rheumatology 1995; 34:365–369. ![]()

12. Suzuki, S, Awaya, G, Okada, Y, et al, Arthroscopic diagnosis of ruptured acetabular labrum. Acta Orthop Scand 1986; 57:513–515. ![]()

13. Farjo, LA, Glick, JM, Sampson, TG, Hip arthroscopy for acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy 1999; 15:132–137. ![]()

14. Zlatkin, MB, Pevsner, D, Sanders, TG, et al, Acetabular labral tears and cartilage lesions of the hip: indirect MR arthrographic correlation with arthroscopy – a preliminary study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(3):709–714. ![]()