Clinical examination of the elbow

History

The history is not very important in elbow problems but some questions should be asked.

• Where is the pain? The location of the pain is usually closely related to the site of the lesion. When the patient indicates exactly where the symptoms are felt, all causes that cannot produce pain in that area are automatically excluded.

• How did it all start? Did the symptoms start spontaneously or has there been any trauma; if so, what type? If the onset was spontaneous, did it begin suddenly or gradually, or as the result of a particular activity?

• What was the evolution? Was there any change in the location, intensity or frequency of the painful episodes? Did the pain spread and, if so, where to? This may indicate the dermatome and, in consequence, the segment in which the lesion must be sought.

• Is there any functional loss?

• Has the elbow ever been swollen? If the swelling came on after trauma, how soon did it appear? Immediate general effusion is probably the result of a haemarthrosis; gradually increasing swelling usually indicates the presence of synovial fluid. Spontaneous swelling may be the result of an impacted loose body or a rheumatoid condition. Localized swelling may occur in bursitis or in some exceptional cases of tennis elbow.

• What influences the pain? Is the pain constantly present, or does it come on during or after either general or specific activity? In an arthrotic or arthritic joint the maintenance of a particular posture at the extreme of the possible range may become very painful. Release from this position is usually very uncomfortable. ‘Twinges’ when picking up objects (e.g. a telephone or a coffee pot) with an outstretched elbow is a well-known symptom in tennis elbow.

• Are any other joints involved? In rheumatoid-type conditions other joints may be affected.

Functional examination

The examination consists of 10 tests: four passive movements and six resisted movements.

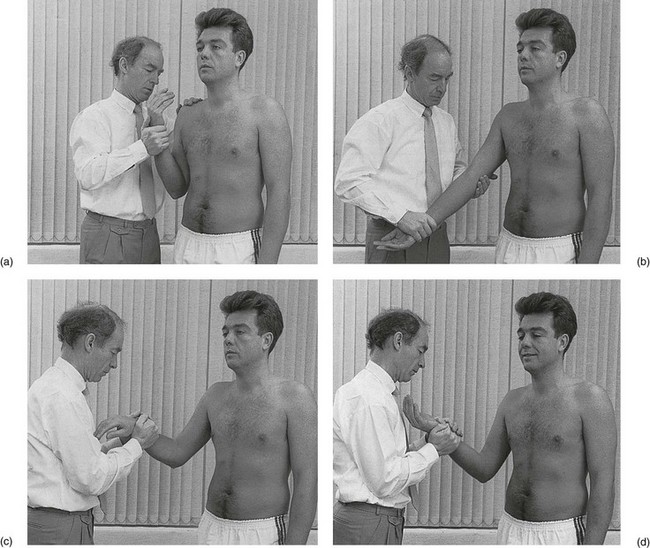

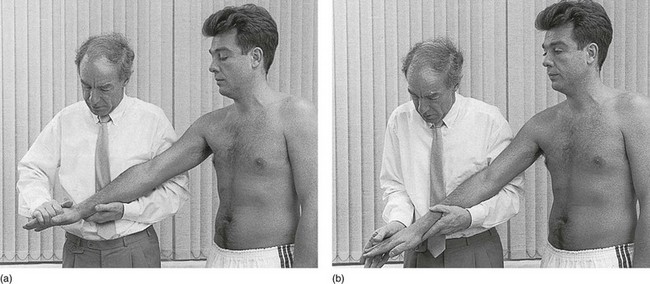

Passive movements

The passive movements (Fig. 16.1) are used to examine the inert structures: the joint, the capsule, the capsular ligaments and the bursae. It is also clear that, by passively testing the elbow, one also indirectly stretches or pinches muscular and tendinous structures.

The range of movement is ascertained and the end-feel noted.

Passive flexion

The examiner places the contralateral hand at the dorsal aspect of the patient’s shoulder to prevent the body from trying to move backwards in order to escape from the pain. The ipsilateral hand takes hold of the patient’s forearm just proximally to the wrist and moves the joint as far into flexion as possible (Fig. 16.1a).

Passive extension

With the contralateral hand, the examiner takes hold of the patient’s upper arm at the level of the olecranon. The ipsilateral hand is put at the distal end of the patient’s forearm. Both hands move in opposite directions so as to extend the elbow (Fig. 16.1b).

Passive pronation

The elbow is bent to a right angle. The examiner stands in front of the patient and grasps the distal forearm just proximal to the wrist with both hands. The heel of the contralateral hand is placed at the palmar aspect of the ulna, the fingers of the other hand at the dorsal aspect of the radius. A simultaneous movement of both hands presses the wrist into full pronation (Fig. 16.1c).

Passive supination

The position of the examiner’s hands is slightly changed: the heel of the ipsilateral hand applies pressure at the dorsal aspect of the ulna and the fingers of the other hand pull at the palmar aspect of the radius. The forearm is twisted into supination as far as it goes (Fig. 16.1d).

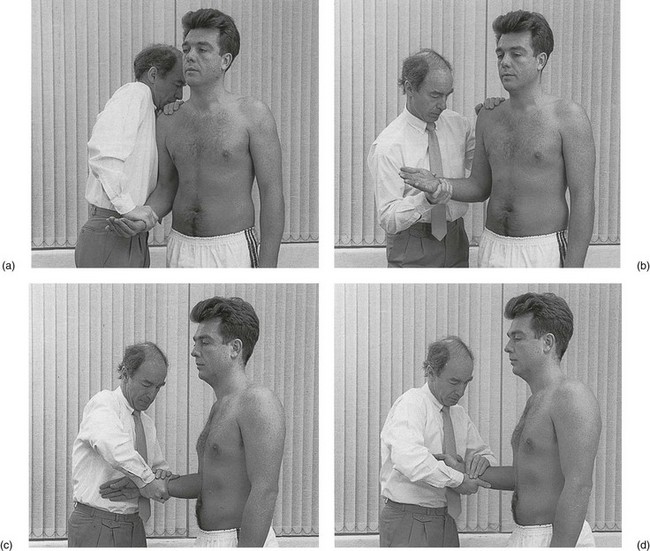

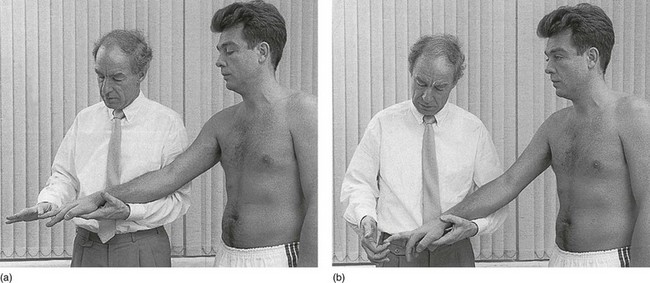

Resisted movements

The same four movements are repeated but against isometric resistance to examine the contractile structures (Fig. 16.2).

Resisted flexion

The patient holds the forearm in supination. The examiner puts the contralateral hand on top of the patient’s shoulder to prevent it from moving upwards during the contraction. The other hand is placed on the distal forearm with the examiner’s forearm held vertically, to prevent the patient’s forearm from moving as the flexor muscles are contracted (Fig. 16.2a).

Resisted extension

Again the contralateral hand is placed on top of the patient’s shoulder. The other one is placed vertically under the patient’s forearm and prevents the arm from moving downwards (Fig. 16.2b). If necessary, in a very strong patient, the examiner’s own elbow may be supported on the thigh.

Pain at the shoulder during this movement has the same applications as painful arc (see online chapter Disorders associated with a painful arc).

Resisted pronation

The patient’s forearm is held in the neutral position between pronation and supination. In order to prevent any movement during the resisted movement, the examiner’s hands should be placed as follows: the ipsilateral hand, held in supination, is placed under the patient’s distal forearm; the contralateral hand, held in pronation, is placed on top. The patient is asked to perform a pronation movement and resistance is supplied by the heels of both hands (Fig. 16.2c).

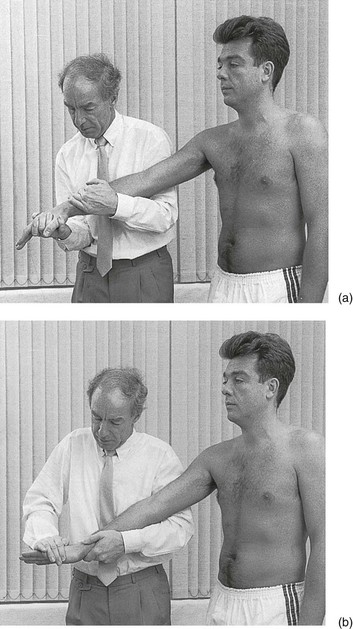

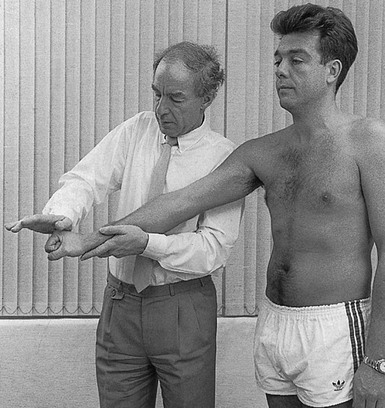

Resisted tests of the flexors and extensors of the wrist

The patient’s elbow is held in extension, so as to put maximum stress on these structures (Fig. 16.3).

Resisted flexion of the wrist

The patient’s hand is held palm downwards. The examiner passes the contralateral arm under that of the patient and grasps the forearm just proximally to the wrist in order to fix the upper limb. The upper arm lies under the patient’s elbow and holds it in full extension. The hand of the other arm is now brought into the palm of the patient’s hand and resists the patient’s attempt to flex the wrist (Fig. 16.3a).

Accessory tests

Resisted extension of the wrist with the fingers actively flexed

The patient is asked to flex the fingers actively by pressing the fingertips into the palm of the hand. Resisted extension of the wrist is now executed, as already described (Fig. 16.4).

Resisted radial and ulnar deviation

With the elbow in extension and the wrist in the neutral position between flexion and extension, radial and ulnar deviation are tested against resistance (Fig. 16.5). These tests differentiate between a lesion of the radial extensors or flexors of the wrist or of the ulnar extensors or flexors.

Resisted extension and flexion of the fingers

When a lesion of the finger extensors has been diagnosed, the examiner may test resisted extension of each finger in turn (Fig. 16.6a) to find out which tendon is at fault.

If a finger flexor is affected, resisted flexion of each finger (Fig. 16.6b) may disclose the exact tendon.

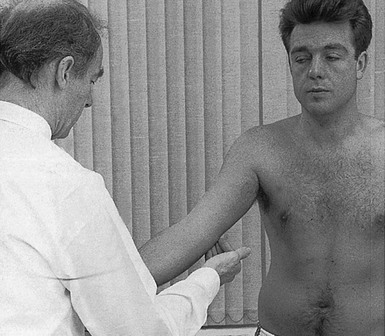

Tinel’s sign

Percussion to the ulnar nerve in the groove between the olecranon and the medial epicondyle (Fig. 16.7) gives rise to distal paraesthesia in the territory of the ulnar nerve – in the forearm and the hand – Tinel’s sign. This test can be used to assess the progress of regeneration of the sensory fibres of the nerve. The most distal point where the pins and needles are felt indicates the limit of regeneration.

Fig 16.7 Accessory test: Tinel’s sign.